Žurnalistikos tyrimai ISSN 2029-1132 eISSN 2424-6042

2022, 16, pp. 72–107 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ZT/JR.2022.3

Tweeting television between innovation and normalization: How Lebanese television and audiences are making use of Twitter in political talk shows

Chirinne Zebib

Instructor at Faculty of Mass Communication & Fine Arts, Al Mareef University.

PhD student at Saint-Joseph University, Lebanon.

Email: chirine.zebib@net.usj.edu.lb

Abstract. Traditional media have progressively integrated newer media practices, with the constant emergence of new digital technologies, without abandoning their former ones. The adoption of Twitter by TV channels and by other social actors during political talk shows is a case in point. This article aims to assess whether the hybridization of TV talk shows and Twitter has innovated or normalized existing patterns of communication. In the former case, by enabling more interaction between different actors and space for audience deliberation, or in the latter case, by reproducing a traditional one-way communication and a centralized network of information that remains controlled and oriented by the elite (journalists and politicians). The incorporation of older and emergent media logic has an impact on the construction and distribution of political information as well as on the power relationships between journalists, politicians, and TV audiences. Besides allowing political talk shows to expand their flow of information, and to promote their news online, hybridized practices have not only altered the way citizens consume and engage with political information but also how they counter-frame traditional political media content by producing new ones. The research methodology consists of descriptive, content, and network analyses of tweets collected from three Lebanese local TV political talk show “Sarelwa2et” (MTV), “Btefro’ aa Watan” (Al Jadeed), and “Vision 2030” (LBCI) between February and March 2022. Results revealed that TV talk shows are making use of Twitter as a top-down transmitter of information and resorting poorly to its interactive potential. Some newer media practices of Twitter, such as @mention and replies are being applied but only to interact with politicians and journalists, failing to engage with a larger array of voices and thus, leading to an elite-centric discourse within the network. Also, tweets are mostly used to inform audiences and promote TV programs. In addition, network analyses of talk shows via hashtags demonstrated the central and not monopolized role of politicians and journalists as influencers, bridges, and quick spreaders of information. Finally, content analysis of dual screeners’ tweets (n=6000) indicated very little space in a Habermasian public sphere. The total of subjective opinions, irony, and attack/insult tweets are still higher than the total of the introduction of new issues and counter-frames tweets.

Keywords: hybrid media system, Twitter, public sphere, mainstream media, dual screening

Received: 2022/12/15. Accepted: 2023/01/30

Copyright © 2022 Chirinne Zebib. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The emergence of the internet and the rapid proliferation of social media platforms have pushed traditional media towards integrating new practices without abandoning their old ones. That has created a challenging environment for journalists (Lasorsa, Lewis, & Holton, 2012). The juxtaposition of older and newer media logic leads to a hybrid media system that fundamentally disrupts both journalistic practices and news construction (Chadwick, 2017). With an ongoing decline in mass media audience (Walters, 2021) and a constant rise in social media popularity in parallel, digital platforms are incarnating a primary place for traditional media to expose their work (Canter, 2015; Belair-Gagnon, 2015), producing, distributing, promoting information, and engaging with audiences. That turns one’s attention to Twitter, which is regarded as having considerable journalistic dynamics (Dagoula, 2019) and viewed as “an ambient news environment, an arena that always contains news” (Ibid, p. 228). Moreover, the platform with its tools is one of the most used by traditional media (Canter & Brookes, 2016; Djerf-Pierre, Ghersetti, & Hedman, 2016):

“As with the Internet itself, Twitter has been heralded to hold interesting possibilities within the context of journalism—potentially bringing journalists and their respective audiences closer to each other through supposedly common Twitter practices like @ messages and retweeting” (Larsson, 2013, p.135).

Television channels are a good illustration of traditional media incorporating new media methods to their programs to retain the viewers’ attention (De Michele, Ferretti, & Furini, 2019) and to promote their episodes online (Molyneux & Mourao, 2017). To guarantee the expansion of their content online and to control the flow of information about episode topics on Twitter, TV programs use official hashtags that usually carry the names of their shows. That hybrid strategy linking diverse content across several media has led to a dual or second screening phenomenon (De Michele, Ferretti, & Furini, 2019); that is, watching TV (first screen) while using a second screen (smartphone, laptop, tablet) to discuss the broadcast content online. The basic definition of this is “a process in which individuals watching television use an additional electronic device or “screen” to access the internet or social networking sites to obtain more information about the program or event they are watching or to discuss it in real-time” (Gil de Zúñiga, García-Perdomo, & McGregor, 2015, p. 5). Dual screening has significantly impacted how citizens consume information and debate public policies (Gil de Zúñiga & Liu, 2017). It can increase citizen engagement and participation in political issues, especially ones expressed by TV political talk shows, and generate online discussions with others by interacting with journalists and political officials through Twitter tools (Bennett, 2012; Howard & Parks, 2012; Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2013). In that regard, citizens commenting on a political TV program can shape the opinions of other users (Boukes & Trilling, 2017) but most importantly, they can influence the content of the TV show and counter-frame it:

“Moreover, the observed hybrid media spaces enable connected audiences to intervene, via Twitter, ‘in’ the production of the content discussed by political talk shows, introducing different angles (problems, causes, and solutions) about the issues proposed by television, and also suggesting alternative information sources (e.g., online journals, blogs, and Facebook Notes) to challenge or strengthen the arguments used by TV hosts and guests” (Iannelli & Giglietto, 2015, p.1009).

The use of Twitter by both TV channels/journalists and TV audiences could create a public sphere where arguments are debated and information is shared (Dahlgren, 2005). However, this assumption relies on the way both actors are employing Twitter affordances and for what purposes.

The study aims to explore the ways journalists and TV audiences are making use of Twitter during a political TV talk show. The main question is whether the hybridization of the two has innovated or normalized existing patterns of communication; in the former case, by enabling more interaction between different actors and spaces for audience deliberation, or in the latter case, by reproducing a traditional one-way communication and a centralized network of information that remains controlled and oriented by the elite (journalists and politicians). Functions attributed to Twitter by TV channels and audiences are essential variables to answer this study’s research question. The study will focus on three Lebanese local TV political talk shows “Sarelwa2et” (MTV), “Btefro’ aa Watan” (Al Jadeed), and Vision 2030 (LBCI) between February 10 and March 31, 2022. The research question is examined by using the theoretical frameworks of innovation versus normalization and the Habermasian public sphere.

Literature review

According to Chadwick (2017), traditional media are integrating new media logic as much as new media are incorporating conventional logic. Therefore, new technologies do not eradicate older media practices but they have led to a hybrid media system: “it reveals how older and newer media logics in the fields of media and politics blend, overlap, intermesh and co-evolve” (Chadwick, 2017, p. 5). The author defines media logic as “technologies, genres, norms, behaviors, and organizational forms” (Ibid, 2017, p. 4). Using Twitter and its practices by TV political talk shows is one example of this media hybridization. Also, this interweaving of different media logics is shaping the power relations among the different actors that produce political information, thus influencing the meanings and flows of political content (Ibid, 2017). The hybridity of media has resulted in the emergence of a greater variety of actors and interactions involved in the construction of political information that was not possible before. Today, citizens and new political actors on social media have the opportunity to reduce the power of traditional media gatekeepers and the capacity to “introduce, amplify, and sustain topics, frames, and actors that come to dominate political discourse” (Jungherr, Posegga, & An, 2019, p. 420). Political content produced during TV talk shows by different actors (mainly journalists, TV hosts, and political figures) and posted simultaneously on Twitter goes under various interpretations and framings by online audiences (mostly citizens, politicians, and activists) to reinforce or challenge the information. As a result, studies have demonstrated the presence of tension between these different players as they aspired for attention and control over the new media spaces (Lewis, 2012; Tandoc & Vos, 2016). Journalists, politicians, citizens, activists, and sometimes TV audiences “create, tap, or steer information flows in ways that suit their goals and in ways that modify, enable, or disable the agency of others, across and between a range of older and newer media settings” (Chadwick, 2017, p. 181).

Several studies have examined the way actors in political communication are exploiting social media by using the innovation versus normalization approaches (Bimber & Davis, 2003; Klinger & Svensson, 2015; Margolis & Resnick, 2000). The same theoretical framework can be applied to comprehend how journalists and TV channels are using digital platforms. The innovative approach claims that journalists would fully apply new media practices and interactive tools of social media, hence adopting a two-way communication that enables interaction between them and an audience that could participate actively in the news-making (Singer, 2014; Chadwick, 2017). In this sense, traditional media would no longer limit their discussions to a certain elite (journalists and politicians), and they would allow more inclusion and participation of the public. Conversely, normalization theory suggests that journalists have integrated new platforms and some new media practices, but that they still hold traditional habits and consider social media simply as “business as usual” (Molyneux et al., 2016). New media platforms are regarded as an extension of conventional media practices used by journalists to maintain control over information (Singer, 2005), and consequently, as reproducing the same power relations among actors offline and online, the elite unaffected (Dagoula, 2019). The normalization theory suggests that journalists favor traditional one-way communication online; if interaction with the public was to happen, it remained limited and controlled (Stromer-Galley, 2014). Several studies on Twitter have shown that political journalists mainly interact with each other, maintaining professional boundaries (Mourão, 2015) as they consider the platform as a news wire to look for sources and provide updates (Lawrence et al., 2014; Molyneux & Mourão, 2017). In a recent study, Fincham (2019) found that political journalists are reproducing their offline insular communities on Twitter, “the study provides evidence of sustained homophily as journalists continue to normalize Twitter” (Ibid, p. 213). Other researchers revealed that most of the time, journalists use Twitter to reiterate statements made by officials and candidates (Coddington, Molyneux, & Lawrence, 2014) and that they adopt humor and self-promotion considerably in their Tweets (Holton and Lewis, 2011; Molyneux, 2015; Mourão, Diehl, and Vasudevan, 2016). Furthermore, journalists use tweets and retweets to promote themselves, the content of their organization, or their guests more so than newer media practices such as replies and quote tweets (Molyneux & Mourão, 2017; De Michele, Ferretti, & Furini, 2019). In one of the few studies about the usage of Twitter by Lebanese television, Kozman & Cozma (2021) found that TV channels are primarily using the platform to distribute and promote their information in one-way communication via original tweets, limiting any type of interaction with the audience.

Finally, the public sphere concept has been examined and revisited by many studies to analyze the impact of social media on journalism (Bruns et al., 2016). Digital platforms, mainly Twitter, have been studied as a new form of the Habermasian public sphere (Hermida et al., 2012) that is defined as a space equally allowing any individual to discuss, exchange, and debate rationally in public affairs. Theoretically, the structure of Twitter is an open and flexible one that allows a horizontal communication process between different users of various societal positions, allowing them to deliberate on political issues. “Twitter has presented itself as an open social networking space that enables Internet users to track breaking news on any occasion, with profiles that can be public and unlocked and accessible to anyone, registered or non-registered.” (Dagoula, 2019, p. 228). By adopting and revisiting the Habermasian public sphere (Athique, 2013; Dahlgren, 2005; Ceron & Splendore, 2019, Chadwick, 2017) without accepting its utopian principle of equality among actors (Bruns & Highfield, 2016; Fraser, 1990), authors have either accepted or rejected considering social media as a public sphere. The latter have questioned the quality of discussions online (Hindman, 2009) and the dangers of homophily and polarization created by social media, contradicting the Habermasian public sphere (Ceron, 2017; Pariser, 2012). In addition, they suggest that a certain hierarchy of interactions persists despite the flexible structure of Twitter (Dagoula, 2019). Those assumptions bring the researchers back to their general research question mentioned above and its sub-questions:

RQ1: How are Lebanese TV stations using Twitter before and during political talk shows?

RQ2: With whom are TV channels interacting during the political shows broadcasting?

RQ3: Which actors are guiding and controlling information flows of TV show networks created on Twitter?

RQ4: How are Lebanese dual screeners use Twitter during TV political talk shows?

Methodology

The methodology is based on descriptive, content, and network analyses of Tweets made by TV channels (N= 608) and TV audiences (N= 6000) between February 10 and March 31, 2022. Content analysis is a “research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication” (Berelson, 1952, p. 18). The method quantifies content into predetermined categories, such as subjects or themes (Bryman et al., 2021). We have adopted two analysis grids with pre-constructed categories. This choice is based on several studies carried out to analyze social media publications of TV channels and their audiences (Kozman & Cozmo, 2021; Molyneux & Mourão, 2017; Iannelli & Giglietto, 2015; Greer & Ferguson, 2011). For the first content analysis, the unit is each tweet of four episodes of three popular TV political talk shows in Lebanon: “Sarelwa2et” (MTV), “Btefro’ aa Watan” (Al Jadeed), and Vision 2030 (LBCI). For the second one, the unit of analysis is tweets published by the audience during the broadcasting of the three shows. 2000 audience tweets were selected randomly from each program (a total of 6000 Tweets) by using the official hashtag [in Arabic] of each TV program

The Twitonomy software was used to collect the data for the three shows. That first data gathering allowed access to all tweets, retweets, mentions, replies, and hashtags published during four episodes of each show. While data on TV audiences were collected by the software Excel add-on NodeXL Pro via its Twitter Search Network importer by entering the official hashtag for each show. The software allowed us to extract tweets, relationships, and user information to calculate key social network metrics. On NodeXL Pro, Twitter API limits the amount of imported content to about 18,000 users per data set. Four data draws (4 episodes) from each TV program were done. Data gathering took place following the next day of each episode’s broadcasting between the selected times. In addition to the analysis of content produced on Twitter, the research will apply network analysis of one episode for each of the three political shows.

Network analysis is considered a complementary method to content analysis on Twitter (Giglietto & Selva, 2014). Instead of focusing on individuals and their attributes, it focuses on the relationships and interactions between people. Hansen et al. (2020) posit that “The network perspective looks at a collection of ties among a population and creates measurements that describe the location of each person or entity within the structure of all relationships in the network” (p. 32). The position of a person or node relative to all others is a primary interest of social network analysis. The structure of Twitter conversations (mentions, replies, and retweets) makes it quite easy to use this analysis (Highfield, Harrington, & Bruns, 2013; Larsson, 2013) via the software NodeXL Pro to calculate and visualize important metrics that characterize networks. The centrality measures of network analysis will identify the presence or absence of elites (media and political actors) in Twitter discussions of political shows. The data collected through the tool mentioned above were grouped into Excel and CSV.

The first sub-question of the study was answered by considering the variables coded as the functions attributed to tweets. The uses include three mutually exclusive categories: Information, interaction, and promotion. Table 1 shows the analysis scheme used in this research for the posts’ content. It includes the categories and characteristics that guide the classification of the content of tweets published by the three political TV talk shows.

Table 1: Analysis scheme for the content of TV Tweets

|

Category |

Characteristics |

|

Information |

A tweet about statements or news made by guests during the show. A tweet about a statement or news made by the host of the show. A tweet with embedded videos/photos or links about discussions, debates, and disputes happening during the show. |

|

Interaction |

A tweet asking a question to the audience before and during the show. A tweet with an opinion poll before and during the show. Replies to user’s questions. |

|

Promotion |

A tweet announcing topics of the show via a video (teaser) or by text to attract an audience. A tweet reminding of the date, and time of the broadcast. A tweet promoting guests of the show. A tweet promoting a TV host. |

A quantitative descriptive analysis of tweets, retweets, mentions, and hashtags made by the three TV channels will be exposed as well to demonstrate what Twitter tools are most used by political shows and with whom they are interacting on Twitter. According to Hejase and Hejase (2013), “descriptive statistics deals with describing a collection of data by condensing the amounts of data into simple representative numerical quantities or plots that can provide a better understanding of the collected data” (p. 272). Therefore, data frequencies and percentages were depicted in tables and figures for clarity. In addition, the descriptive analysis adds value to the discussion of results. For instance, a high usage of tweets and retweets and a low usage of interactive tools such as mentions and replies would mean that TV channels are not fully integrating the interactive affordances of the platform (Molyneux & Mourão, 2017). In that case, traditional media are normalizing Twitter in a broadcasting top-down logic and limiting innovative media logic (the social media’s conversational bottom-up logic) (Bosner & Nagel, 2020). These analyses will provide answers to the first two sub-questions.

The third sub-question will be answered by analyzing the networks of conversations and relations of one episode for each political talk show on Twitter by using quantitative network centrality measures. Each measure will be coded as a user category in the network since they can be used as indicators of influence, popularity, influence, and gatekeeper/bridge (Hansen et al., 2020; Scott & Carrington, 2011). Table 2 summarizes the main centrality measures chosen and their user categories.

Table 2: Measures centrality for network analysis

|

Measure centrality |

User category |

|

In-degree: Incoming relations/links Twitter users that are mentioned, retweeted, or replied to |

High in degree: Popular / influencer / conversational hub |

|

Out-degree: Outcoming links/ number of tweets sent out by a particular user |

High out-degree: Active tweeter / aims to reach user’s attention / high level of engagement |

|

Betweenness: measures the number of times a Twitter user lies on the shortest bridge/gatekeeper path between other users |

High betweenness: Bridge/gatekeeper |

|

Closeness: Measures the distance of a node (Twitter user) to all others in the network |

High closeness: User that can reach other users very quickly / closest to all in the network |

Finally, to answer the last sub-question of the research, the variables coded were the functions attributed to TV audiences’ tweets. They include eight categories that are not mutually exclusive: Information/streaming/report, opinion/comment, request for interaction, the introduction of new issues/angles/sources/analysis, attack/insult, jokes/irony, emotion, and others. This content analysis will allow us to determine the quality of discussions and debates among TV audiences on Twitter. As mentioned before, the quality of the dialogue is an important criterion for the development of a public sphere online. Table 3 shows the analysis scheme used for the Tweets content made by TV audiences. It includes the categories and characteristics that guide the classification of the conte nt of tweets.

Table 3: Analysis scheme for the content of tweets made by TV audiences

|

Category |

characteristics |

|

Information/streaming/report |

Tweets containing statements or sentences pronounced by political guests or TV hosts or other guests |

|

Opinion/comment |

Tweets expressing an opinion about the content of the show, the guests, or the TV host |

|

Request for interaction |

Tweets asking questions to guests or host |

|

Introduction of new issues/angles/sources/analysis |

Tweets discussing new topics or information that was ignored by the talk show; personal analysis about topics discussed on TV, counter-frames Tweets introducing different information sources to challenge or reinforce the ongoing TV discussion via links to past information (article, video, or photo) that show the contradictory statements of politicians |

|

Attack/insult |

Tweets with vulgar or violent language, threats, or provocations |

|

Jokes/irony |

Tweets containing funny comments, sarcasm, and jokes |

|

Emotion |

Tweets expressing love, hate, or sadness, using multiple exclamation marks or emoticons |

|

Other |

Tweets that cannot be classified into any of the above categories |

Findings

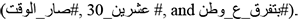

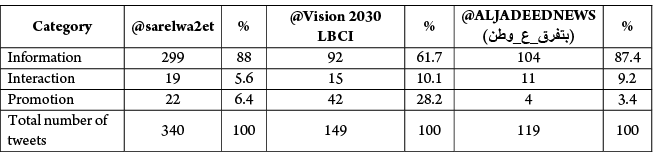

Table 4 demonstrates that the three TV talk shows are primarily using Twitter to broadcast information to users. TV programs “Sarelwa2et” (88%) and “Btefro’ aa watan” (87.45%) have approximately the same results, while “Vision 2030” is slightly behind with 61.7%. The three programs have therefore normalized the use of Twitter in a broadcasting top-down logic, favoring a unidirectional way of communication as they are used to on television. Moreover, the reiteration through tweets of statements pronounced by guests or hosts during TV shows is adopted by broadcasters to expand information to a wider audience and maintain control over the flow of information. A second observation made in the same table is that “Vision2030” and “Sarelwa2et” have a higher usage of Twitter to promote their episodes, guests, and even sometimes their hosts. Promotion or self-promotion tweets are usually accompanied by a hashtag aimed at attracting and increasing public attention before or during the talk show (De Michele, Ferretti, & Furini, 2019). Promotional tweets can similarly have videos that look like teasers to increase interest in the audience about the episode’s topics (Greer & Ferguson, 2011).

Table 4: Number of tweets published by the three TV programs by categories

All three programs have a very low percentage of interactive tweets; the highest percentage for four episodes of Vision 2030 is 10.1%, and the lowest is for the talk show “Btefro’ aa watan” (3.4%). TV channels are reducing their interactions with users to a few questions and opinion polls asked before or during the show. Interaction here is regarded more as a means to gauge public opinion about a certain topic rather than conversing with the public (Marchetti & Ceccobelli, 2013). For instance, most of the interactive tweets of “Vision 2030” (12 out of 15) are opinion polls posted to users.

Figure 1. Example of a controlled interactive tweet by the TV program Vision 2030

Questions or opinion polls seem to engage more TV audiences, but the interaction with the public remains limited or even quasi-absent. In fine, talk shows are using Twitter to distribute and promote information that is already produced for television and rarely interact online with their audiences. They are dealing with the platform as a traditional media tool that enables wider reach, treating it as a means for top-down communication (Kozman & Cozma, 2021).

Figure 2. Percentage of the total number of tweets by categories for each TV political talk show

The first analysis focuses more on determining if the content of Tweets has an interactive purpose rather than if twitter’s interactive tools have been used or not by TV accounts. To do that, a descriptive analysis of different types of tweets and interactive affordances of Twitter will be carried out to examine; whether TV channels are using the new media logic of Twitter and with whom they are talking on the network.

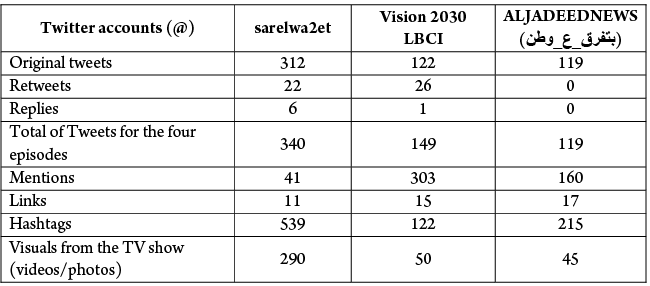

Table 5: Analytics of the tweets published by TV programs

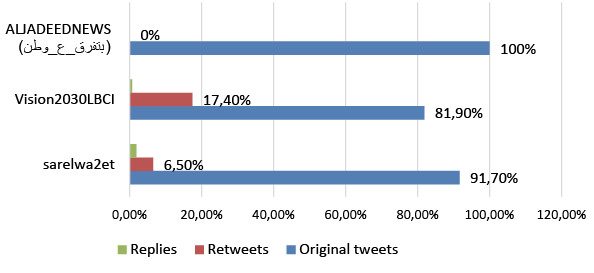

Figure 3. Types of tweets published by TV show Twitter accounts

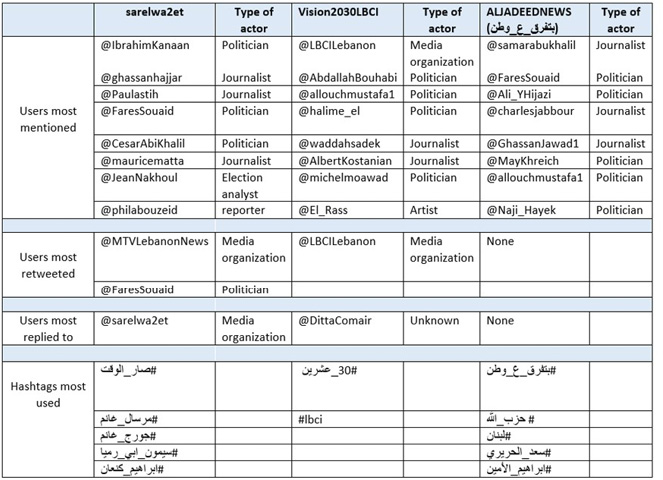

Figure 3 shows that original tweets accounted for 100%, 91.7%, and 82% of all tweets published by “Btefro’ aa watan,” “Sarelwa2et,” and “Vision 2030,” respectively. For traditional media, normal tweets look more like the one-way interaction that journalists are familiarized with using tweets just to broadcast their message to their followers or share it with a wider audience. Consequently, the three talk shows have made no or little use of retweets and replies. With 17.4%, “Vision 2030” has retweeted more than “Sarelwa2et” (6.5%) and “Btefro’ aa watan” which did not retweet at all. Retweets, being the rebroadcasting of messages originally published by others, are significant tools to diffuse information to a wider audience but most importantly, it could be an indicator of audience participation in news making: “Retweeting is an indication of a journalist’s ‘‘opening the gates’’ to allow others to participate in the news production process” (Lasorsa, Lewis, & Holton, 2012, p. 26). Results might insinuate that “Vision 2030” and “Sarelwa2et” have slightly started to “open the gates”, however, if we look deeper into the profiles of the persons they retweeted, we can conclude that it is not yet the case. Table 6 shows that the totality of retweets made by “Vision 2030” are from their TV channel (LBCI), and retweets of “Sarelwa2et” are as well from their own media organization (MTV) and one politician.

Table 6: Accounts most mentioned, retweeted, and replied to, as well as hashtags most included in tweets

In addition, the percentage of replies over the total number of tweets is almost inexistent (1.8% and 0.7% for “Sarelwa2et” and Vision 2030”, respectively) or even null (“Btefro’ aa watan”). Most of the replies were to tweets published by the TV programs themselves, and only one reply by “Vision 2030” was addressed to an unknown account. Usually, talk shows will reply to their tweets to circumvent Twitter’s 140-character limitation and write longer comments (Molyneux & Mourão, 2017). In addition, mentions by journalists are regarded as interactive and innovative tools since TV channels can mention users to engage in a conversation. Nevertheless, Table 6 reveals that the majority of the people mentioned in the three programs are either politicians, journalists, or media organizations. Thus, the result implies that talk shows are only engaging in conversations with specific actors mentioned above, creating a form of intra-elite conversation on Twitter (Dagoula, 2019). Moreover, when TV channels mention their institutions and journalists, the tool becomes an indicator of self-promotion. The usage of links included in tweets was low for all programs, and most of the time, they were referring to content from their news institution. In this way, TV programs via their links can aim at orienting and directing what users should read. Finally, talk shows have included at least one hashtag in each of their tweet (1.6, 1.2, and 1.8 hashtags per tweet posted by “Sarelwa2et,” “Vision 2030,” and “Btefro’ aa watan,” respectively). The use of official hashtags by the shows enables TV channels to organize online conversations around the main topics exposed on their TV shows and to increase their visibility and popularity. In this regard, the use of hashtags can be an indicator of both promotion (De Michele, Ferretti, & Furini, 2019) and information flow control (Gainous & Wagner, 2014).

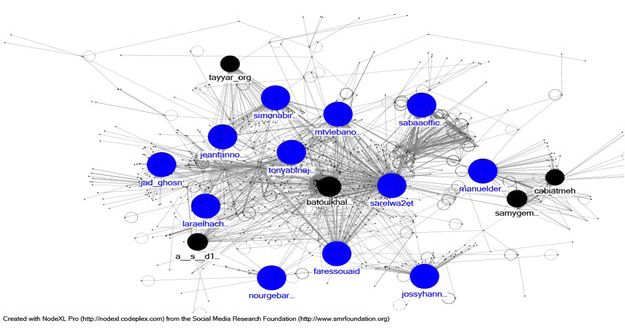

In summary, the research’s results revealed how and for what purposes TV talk shows are using Twitter and with whom they interact. The network analysis for one episode of each talk show (in total three networks) will determine structurally important nodes (users) in the network. The network for each show is all relationships and interactions among people that have included the official hashtag of the TV program in their tweets. Centrality measurements will allow us to identify central actors in the network. A high centrality signifies central locations and dominance within the networks.

Table 7: Top 15 users rank by in-degree and out-degree centrality

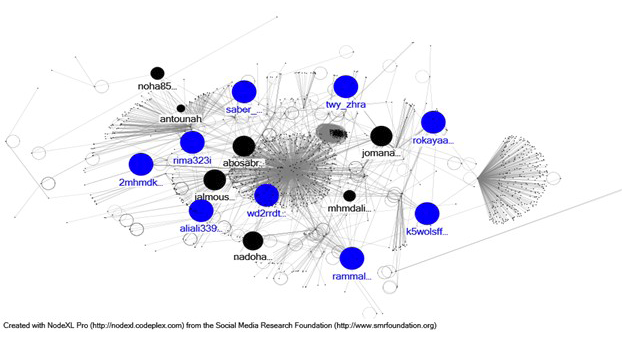

The highest in-degrees for the three programs are either media organizations (AlJadeednews, LBCI, and MTV Lebanon news), journalists (Samar Abou Khalil, Albert Kostanian, Jad Ghosn, and Tony Abi Najem), politicians (Simon Abi Ramia, Michel Moawad, Fares Souaid, and Halima Kaakour) or the programs themselves (“Sarelwa2et” and “Vision 2030”). ‘High in degree’ in this case, means that users are very popular in the network and have been referenced mostly by other users via mentions, replies, and retweets. However, the network is not dominated by the popularity of the elite; some political activists or normal social media users have high in-degrees as well (Jossy Hannakh, Batoul Khalil, Assaad Moawad, and Zainab El Zein). Nodes with the highest out-degrees in the three networks are normal active users that have tweeted many times during the talk shows to get the attention of either guests, hosts, or programs themselves via mentions, replies, and retweets. However, some accounts can be suspected to be trolls as they do not exist anymore, have fake profile pictures, carry username accounts with random combinations of letters and numbers, or have more than one account on Twitter.

Figure 4. Visualization of the highest in-degree nodes in the network “Sarelwa2et”

Figure 5. Visualization of the highest out-degree nodes in the network “Btefro’ aa watan”

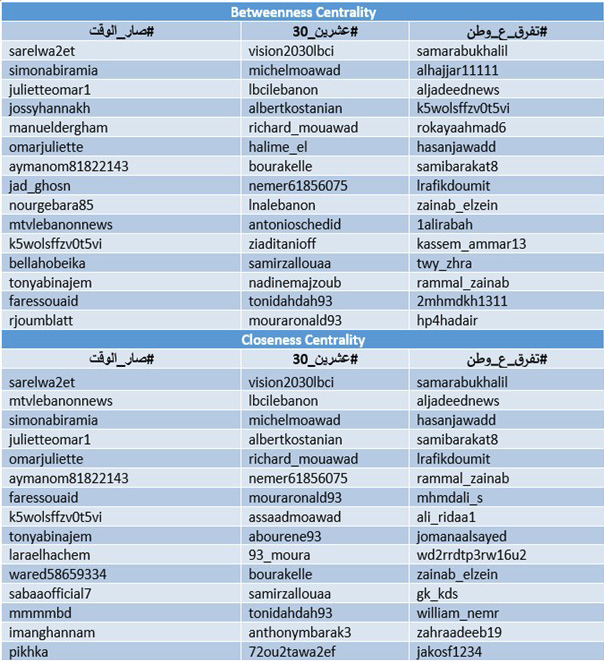

Table 8: Top 15 users rank by betweenness and closeness centrality

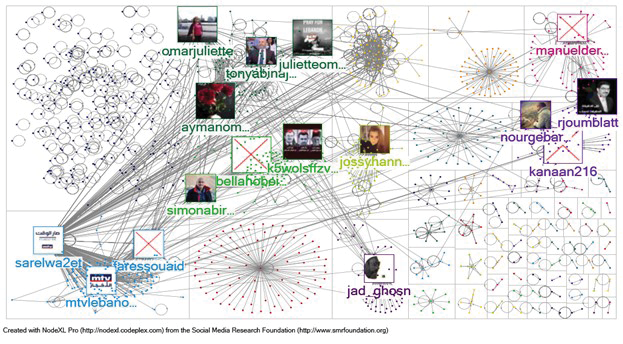

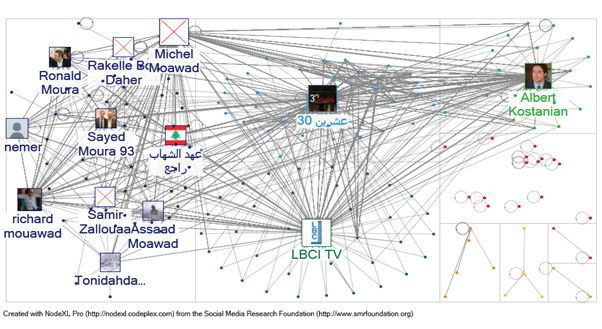

Media institutions (LBCI, AlJadeednews), TV program accounts (salrelwa2et, vision2030lbci), politicians (Simon Abi Ramia, Michel Moawad, and Halima Kaakour), and journalists (Albert Kostanian, Jad Ghosn, and Samar Abu Khalil) have one of the highest betweenness centrality in the networks. These are essential actors in controlling and maintaining the information flow and conversations in the network. They can also be considered bridges since they can diffuse information from one subgroup to another, thus playing a connecting role between non-connected clusters within the network. Elite actors are not the only gatekeepers in the three networks; active users on social media (Rislan El Hajjar, Juliette Omar, Jossy Hannakh, and Hassan Jawad) also play a central role in directing the information flow. However, many of the accounts with high betweenness centrality (except journalists, politicians, and media organizations) are suspected to be trolls for the same reasons mentioned above, especially in the network of “Btefro’ aa watan”. Finally, in terms of closeness centrality, the leading users are media organizations (MTV Lebanon news, LBCI, and Al Jadeed news), journalists (Samar Abu Khalil and Albert Kostanian), and politicians (Simon Abi Ramia and Michel Moawad). Actors with high closeness centrality receive information more quickly and can reach others in the network rapidly since they are the closest to every user. In addition, the closeness centrality of some active users on the network comes right after certain journalists and politicians mentioned before. However, once again, and especially for the talk show “Btefro’ aa watan” some of the accounts with high closeness centrality are suspected to be trolls. Ultimately, the network analysis revealed that offline media and political elite have a central role but not a dominant one in the networks of the three shows. Politicians and journalists remain the first and main hubs of conversations, the bridges, and the gatekeepers of information in the network. However, they are directly followed by active normal citizens that have made an important place for them in the network, even though some of them are suspected of being troll accounts.

Once we have analyzed the structure of the networks, the researchers’ last analysis is about the content of tweets published by dual screeners within these networks to determine the nature and quality of conversations and citizen deliberations.

Figure 6. Visualization of the highest betweenness centrality nodes in the “Sarelwa2et” network

Figure 7. Visualization of the highest closeness centrality nodes in the network “Vision 2030”

Table 9: Number of tweets published by dual screeners by categories

|

Category |

sarelwa2et |

% |

ALJADEED NEWS |

% |

Vision 2030 LBCI |

% |

|

Information/streaming/report |

612 |

28.8 |

848 |

40.9 |

1704 |

84.6 |

|

Opinion/comment |

615 |

28.9 |

522 |

25.2 |

169 |

8.4 |

|

Request for interaction |

88 |

4.1 |

55 |

2.6 |

26 |

1.3 |

|

Introduction of new issues, angles, sources, and analysis |

291 |

13.7 |

212 |

10.2 |

20 |

1 |

|

Attack/insult |

164 |

7.7 |

226 |

10.9 |

22 |

1.1 |

|

Jokes/irony |

231 |

10.9 |

99 |

4.8 |

22 |

1.1 |

|

Emotion |

34 |

1.6 |

54 |

2.6 |

44 |

2.2 |

|

Other |

92 |

4.3 |

58 |

2.8 |

11 |

0.5 |

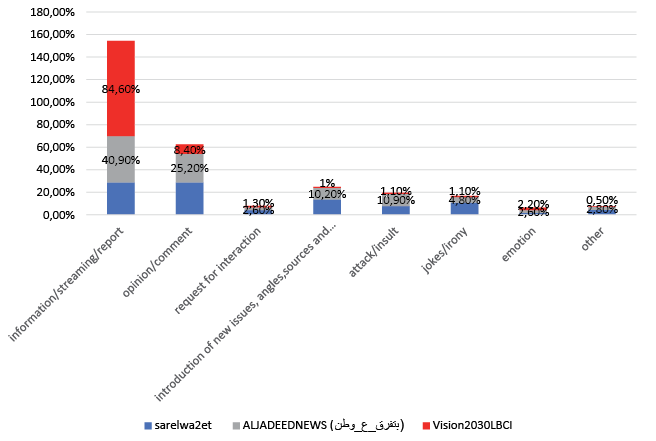

Table 9 shows a general tendency for the use of Twitter by dual screeners of each TV program. Users are primarily tweeting information already pronounced by guests and hosts during the broadcasting of programs or reporting what is happening during the talk shows. Dual screeners of “Vision 2030” have the highest percentage in this category and are followed respectively by “Btefro aa Watan” with 40.9%, and “Sarelwa2et” with 28.8%. The second important function attributed to the platform by second screeners is the expression of opinion or comment about the talk show, topics, guests, and hosts (see Figure 8). Dual screeners of “Sarelwa2et” are the most active in tweeting their opinions (28.9%) and users of “Btefro’ aa Watan” come right behind them at 25.2%.

Figure 8. Percentage of the total number of tweets published by dual screeners by categories

Moreover, the introduction via tweets of counter-frames, counter topics and their analysis through different angles than the ones presented on TV is relatively significant for the public of “Sarelwa2et” (13.7%) and “Btefro aa Watan” (10.2%) in comparison to that of the audience of “Vision 2030” (1%). This category is essential to determine the nature of conversations since deliberation requires rational exchanges of arguments and counter-arguments. In terms of interaction, dual screeners from all TV channels made minimal requests with guests or hosts of the talk show online with the highest percentage of 4.1 (Sarelwa2et). Furthermore, the amount of attack/insult tweets is more important among “Sarelwa2et” and “Btefro’ aa Watan” dual screeners than those of “Vision2030”. Joke/irony is more present in tweets published by the public of “Sarelwa2et” (~11%) whereas it is much lower for the two other programs. Lastly, the number of emotional tweets barely exceeded 2% for all talk shows. Ultimately, the content analysis of tweets posted by dual screeners has demonstrated that the quality of the dialogue among users is still mediocre compared to the Habermasian ideal. The total of tweets categorized as jokes/irony, attack/insult, and emotion is higher for the three shows (respectively 20.2%, 18.3%, and 4.4% for “Sarelwa2et”, “Btefro aa Watan”, and “Vision 2030”, respectively) than the aggregate percentage of the two important categories in terms of quality and nature of dialogue: requests for interaction and introduction of new issues/angles/sources/analysis. Dual screeners have tweeted more about their own opinions and statements pronounced on TV by guests and hosts than to debate and challenge political information by counter-framing and argumentation (see Figure 8).

Discussion and conclusion

Through descriptive, content, and network analyses, the present study was able to provide answers to the research questions above.

First, the three Lebanese TV programs examined in this paper are using Twitter in a one-way publishing model by broadcasting information to users in a unidirectional way, similar to traditional media logic used on TV: “we write, you read” (Deuze, 2003, p. 220). The platform is being used as a tool for information diffusion and promotion via original tweets, rather than for the innovative and interactive affordances of Twitter such as retweets, replies, and mentions. The latter was only used to engage and interact with media organizations, journalists, and politicians. Interactions with normal users were limited to the posting of opinion polls, aiming at measuring public opinions about the topics of the programs. Thus, even when applied, interactive affordances are integrated and normalized to fit older media logics and practices, allowing TVs and journalists to hold on to their old journalistic habits but in an online environment. In addition, most of the tweets are only the diffusion of what is happening during talk shows via links from media organizations or pictures and videos taken from TV studios. There are very few materials produced for the platform by TV programs or their hosts. Hashtags are briefly announced at the beginning of the show but the audiences’ tweets are rarely reported by TV hosts. Some studies have discovered significant cross-national differences concerning the quoting of tweets in traditional media. Broersma and Graham (2012) showed that British newspapers were more prone to cite tweets from non-elite users than tweets of politicians, whereas Dutch journals avoided non-elite tweets in favor of declarations tweeted by political figures. Therefore, Twitter affordances can be regarded as points of tension between traditional practices and routines of television and journalists, and newer ones that enable more audience interactions. However, some studies have suggested that in the long-run, traditional practices and norms of journalists might change to go with the flow with “what works” on Twitter (Broersma and Graham, 2016, p. 99). In this case, TV programs will need to engage with a wider audience on Twitter and not restrict interactions to journalists and politicians. Mondragon et al.’s (2017) argue for the necessity to modify the content, formats, and tools of TV shows and adjust them to the online feedback of dual screeners.

Second, the descriptive analysis revealed that TV shows made use of retweets, mentions, and replies to engage only with their small circle of actors (journalists, media organizations, and politicians), failing to interact with a larger array of voices and thus leading to an elite-centric discourse within their networks. Despite its open and flexible structure, Twitter does not guarantee the participation of all users in the discussion, especially if talk show accounts are avoiding to endorse a bottom-up communication approach. In that regard, the principle of inclusion in Habermas’s public sphere is not achieved. The reproduction of an elite-centric discourse on Twitter can be explained in Lebanon by the strong relations between television channels and politicians. Political parallelism is a distinct characteristic of the Lebanese media system (El-Richani, 2016). Hence, the Lebanese media landscape is portrayed as “polarized and its dominant feature is the interwoven relationship between media and the politicians in Lebanon” (Harb, 2013, p. 41). These strong connections and affiliations are extrapolated on Twitter and might exclude or ignore any actors or topics that might challenge the traditional political content of TV shows. Besides, the reinforcement of ideas and information exposed during TV shows with the interaction of an insular group of users will contribute to transforming the networks into echo chambers.

Third, the network analysis has indicated the central position of journalists, media organizations, and politicians in the Twitter networks of political TV shows. The mentioned actors are strong influencers, gatekeepers, and spreaders of information. However, the analysis has revealed that certain normal users were holding important positions in the networks, enabling the reinforcement or the introduction of new information and topics. Nevertheless, their low presence maintains a hierarchical structure of the network, preventing the absence of prominent elite actors.

Fourth, the content analysis of dual-screener tweets was important to determine the level and quality of discussions on Twitter. Habermas (1992) describes the public sphere as a forum where citizens can exchange arguments on political issues rationally and critically. In contrast, critical thinking was not visible in TV audiences’ tweets since they primarily used Twitter to repeat the statements of guests and hosts during the shows. The significant total of insult, irony, and emotional tweets challenges the concept of Habermas in terms of the quality of conversations. The number of tweets introducing new frames and analyses to contest or reinforce ongoing TV discussions is still very low to consider Twitter as an inclusive and dynamic space for political debate.

Twitter in Lebanon is still limited to a niche of active citizens. Out of a 6.8 million population (World Bank, 2020), barely half a million are active Twitter users (Dataportal, 2022). The broadcasting of 12 episodes from the three talk shows has generated an overall volume of 24,210 tweets by using their official hashtags during airtime. Therefore, the findings of this study have to be seen in the light of some limitations. The first one is the representativeness of the sample collected for this study whereby 7,446 were unique contributors of tweets, making up only 5% of the estimated Lebanese Twitter community. Sample representation could be improved by longer-term research that would better encompass dual screeners and the Lebanese Twitter population. In an earlier study about social media as a predictive tool for election results, Jungherr et al. (2011) demonstrated that data collection, more specifically the selection of political parties and the determination of period, has a significant impact on predicting election results or gauging public opinion. In the present study, the selection of the TV shows and the short time interval of data collection could have an important impact on the research findings. In addition, a larger sample of posts would most probably require the use of supervised machine learning for content analysis, which was not the case for this study. Secondly, the absence of demographics about dual screeners might also be considered a limitation of the research. The little data available about users on digital platforms is often incomplete, wrong, or not necessarily made public. The absence of these socio-demographic data and the impossibility of socially locating the authors of the messages pose a major obstacle: that of the representativeness of the population studied. Finally, the growing presence of automated accounts or bots can also be regarded as a limitation to the legitimacy of the collected corpus on Twitter. Differentiating between real accounts, and therefore real opinions or reactions of users, and fake ones remains an obstacle for researchers during analysis.

However, Twitter remains an important space for topics related to politics (Verweij & Van Noort, 2014) and several studies have found an increase in tweets published during political media events on TV (Larsson & Moe, 2012; Vaccari, Chadwick, & O’Loughlin, 2015). Even with a restricted number of Twitter users, second screeners are contributing to the propagation of TV show content online and are attracting public attention (Ceron & Splendore, 2019). The inclusion and participation of TV audiences could be improved by the innovative integration of Twitter and its interactive affordances by TV shows. The ongoing development of technologies in communication and information will inevitably lead to more demands on the side of the public to play a greater role in the production of political information. This larger participation and inclusion cannot generate a public sphere if online discussions are reduced only to attack, insult, and irony. Improvement of media and digital literacy from users could pave the way to a better quality of dialogue and conversations. Finally, trolls and political bots are a real growing danger today, and they threaten to ruin any chance of an online public sphere (Keller & Klinger, 2018). Their online presence in every political debate, electoral campaign, and even political TV show is producing more political polarization and isolation, obliterating any opportunity for healthy and constructive deliberations. For this purpose, further research is recommended on different methods to detect bots’ activities and their impacts on political communication online. In addition, supplementary research should examine the ability and capacity of traditional media outlets to integrate and make more use of social media platforms to address and engage users, more specifically, the youth. Finally, academic research and universities’ curriculum shall play a significant role in preparing students and new generations for the use of social media in efficient and productive manners and improve digital literacy in a way that transforms the present and mostly superficial comments and conversations into constructive and deliberate public debates.

References

Athique, A. (2013) Digital media and society: An introduction. Malden, MA, USA: Polity Press.

Belair-Gagnon, V. (2015) Social media at BBC news: the re-making of crisis reporting. New York: Routledge.

Bennett, W. L. (2012) ‘The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), pp. 20-39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212451428

Berelson, B. (1952) Content analysis in communication research. New York: Free Press.

Bimber, B. and Davis, R. (2003) Campaigning online: The internet in U.S. elections. Cary: Oxford University Press.

Bossner, F. and Nagel, M. (2020) ‘Discourse networks and dual screening: Analyzing roles, content, and motivations in political Twitter conversations’, Politics and Governance, 8(2), pp. 311-325. doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2573

Boukes, M. and Trilling, D. (2017) ‘Political relevance in the eye of the beholder: Determining the substantiveness of TV shows and political debates with Twitter data’, First Monday, 22(4), p. 1. doi: https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i4.7031

Bruns, A. and Highfield, T. (2016) ‘Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere, in A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbø, A. O. Larsson & C. Christensen (Eds.). The Routledge companion to social media and politics. 1st edn, New York: Routledge, pp. 56-73. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299-5

Canter, L. (2015) ‘Personalised tweeting: The emerging practices of journalists on twitter’, Digital Journalism, 3(6), pp. 888-907. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.973148

Canter, L. and Brookes, D. (2016) ‘Twitter as a flexible tool: How the job role of the journalist influences tweeting habits’, Digital Journalism, 4(7), pp. 875-885. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1168707

Ceron, A. and Splendore, S. (2019) ‘Cheap talk’’? Second screening and the irrelevance of TV political debates’, Journalism (London, England), 20(8), pp. 1108-1123. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919845443

Ceron, A. and SpringerLink (Online service). (2017) Social media and political accountability: Bridging the gap between citizens and politicians. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Chadwick, A. (2017) The hybrid media system: Politics and power. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Coddington, M., Molyneux, L. and Lawrence, R. G. (2014) ‘Fact-checking the campaign: How political reporters use Twitter to set the record straight (or not)’, The International Journal of press/politics, 19(4), pp. 391-409. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214540942

Dagoula, C. (2019) ‘Mapping political discussions on Twitter: Where the elites remain elites’, Media and Communication (Lisboa), 7(1), pp. 225-234. doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i1.1764

Dahlgren, P. (2005) ‘The internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation’, Political Communication, 22(2), pp. 147-162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600590933160

DataReportal (2022) Digital 2022 Lebanon. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-lebanon (Accessed: 19 May 2022).

De Michele, R., Ferretti, S., and Furini, M. (2019) ‘On helping broadcasters to promote TV shows through hashtags’, Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78(3), pp. 3279-3296. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-6510-7

Deuze, M. (2003) ‘The web and its journalisms: Considering the consequences of different types of news media online’, New Media & Society, 5(2), pp. 203-230. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444803005002004

Djerf-Pierre, M., Ghersetti, M. and Hedman, U. (2016) ‘Appropriating social media: The changing uses of social media among journalists across time’, Digital Journalism, 4(7), pp. 849-860. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1152557

El-Richani, S. (2016) The Lebanese media: Anatomy of a system in perpetual crisis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Enli, G., Bruns, A., Skogerbo, E., Larsson, A. O. and Christensen, C. (2015) The Routledge companion to social media and politics. New York: Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299

Fincham, K. (2019) ‘Exploring political journalism homophily on Twitter: A comparative analysis of US and UK elections in 2016 and 2017’. Media and Communication (Lisboa), 7(1), pp. 213-224. doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i1.1765

Foster, L., Clark, T., Sloan, L. and Bryman, A. (2021) Bryman’s social research methods. 6th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fraser, N. (1990) ‘Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy’, Social Text, 25-26 (25-26), pp. 56-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/466240

Gainous, J. and Wagner, K. (2014) Tweeting to Power: The social media revolution in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Giglietto, F. and Selva, D. (2014) ‘Second screen and participation: A content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets’, Journal of Communication, 64(2), pp. 260-277. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12085

Gil de Zúñiga, H. and Liu, J. H. (2017) ‘Second screening politics in the social media sphere: Advancing research on dual screen use in political communication with evidence from 20 countries’, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(2), pp. 193-219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1309420

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Garcia-Perdomo, V. and McGregor, S. C. (2015) ‘What is second screening? Exploring motivations of second screen use and its effect on online political participation’, Journal of Communication, 65(5), pp. 793-815. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12174

Graham, T., Jackson, D. and Broersma, M. (2016) ‘New platform, old habits? candidates’ use of Twitter during the 2010 British and Dutch general election campaigns’, New Media & Society, 18(5), pp. 765–783. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814546728

Greer, C. F. and Ferguson, D. A. (2011) ‘Using Twitter for promotion and branding: A content analysis of local television Twitter sites’, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55(2), pp. 198-214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2011.570824

Habermas, J. (1992) ‘Further reflections on the public sphere’, in C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 421-461.

Hansen, D., Himelboim, I., Shneiderman, B. and Smith, M. A. (2020) Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: Insights from a connected world. 2nd edn. United States: Morgan Kaufmann.

Harb, Z. (2013) ‘Mediating internal conflict in Lebanon and its ethical boundaries’, in D. Matar & Z. Harb (Eds.), Narrating conflict in the Middle East: Discourse, image and communications practices in Lebanon and Palestine. London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 38-57.

Hejase, A.J. and Hejase, H.J. (2013) Research Methods: A Practical Approach for Business Students. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Masadir Incorporated.

Hermida, A., Fletcher, F., Korell, D. and Logan, D. (2012) ‘SHARE, LIKE, RECOMMEND: Decoding the social media news consumer’, Journalism Studies (London, England), 13(5-6), pp. 815-824. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2012.664430

Highfield, T., Harrington, S., & Bruns, A. (2013) ‘Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom’, Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), pp. 315-339. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.756053

Hindman, M. (2009) The myth of digital democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Holton, A.E., and Lewis, S.C. (2011) ‘Journalists, social media, and the use of Humor on Twitter’, Electronic Journal of Communication, 21(1/2), pp. 1-22. 2011-Holton-Lewis-2011-EJoC.pdf (sethlewis.org)

Howard, P. N. and Parks, M. R. (2012) ‘Social media and political change: Capacity, constraint, and consequence’, Journal of Communication, 62(2), pp. 359-362. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01626.x

Iannelli, L. and Giglietto, F. (2015) ‘Hybrid spaces of politics: The 2013 general elections in Italy, between talk shows and twitter’, Information, Communication & Society, 18(9), pp. 1006-1021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1006658

Jungherr, A., Posegga, O. and An, J. (2019) ‘Discursive power in contemporary media systems: A comparative framework’, The International Journal of press/politics, 24(4), pp. 404-425. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219841543

Jungherr, A., Jürgens, P. and Schoen, H. (2011) Why the Pirate Party Won the German Election of 2009 or The Trouble With Predictions: A Response to Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T. O., Sander, P. G., & Welpe, I. M. Predicting Elections With Twitter: What 140 Characters Reveal About Political Sentiment’, Social Science Computer Review, 30(2), pp. 229-234. doi: 10.1177/0894439311404119

Keller, T.R. and Klinger, U. (2018) ‘Social Bots in Election Campaigns: Theoretical, Empirical, and Methodological Implications’, Political Communication, 36(1), pp. 171-189. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1526238

Klinger, U. and Svensson, J. (2015) ‘The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach’, New Media & Society, 17(8), pp. 1241-1257. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

Kozman, C. and Cozma, R. (2021) ‘Lebanese television on Twitter: A study of uses and (dis)engagement’, Journalism Practice, 15(4), pp. 508-525. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1732832

Larsson, A. O. (2013) ‘Tweeting the viewer-use of twitter in a talk show context’, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(2), pp. 135-152. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.787081

Larsson, A. O. and Moe, H. (2012) ‘Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedish election campaign’, New Media & Society, 14(5), pp. 729-747. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811422894

Lasorsa, D., Lewis, S. and Holton, A. (2012) ‘Normalizing Twitter’, Journalism Studies, 13(1), pp. 19-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2011.571825

Lawrence, R. G., Molyneux, L., Coddington, M. and Holton, A. (2014) ‘Tweeting conventions: Political journalists’ use of twitter to cover the 2012 presidential campaign’, Journalism Studies (London, England), 15(6), pp. 789-806. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.836378

Lewis, S. C. (2012) ‘The tension between professional control and open participation: Journalism and its boundaries’, Information, Communication & Society, 15(6), pp. 836-866. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150

Marchetti, R. and Ceccobelli, D. (2016) ‘Twitter and television in a hybrid media system: The 2013 Italian election campaign’, Journalism Practice, 10(5), pp. 626-644. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1040051

Margolis, M. and Resnick, D. (2000) Politics as usual: The cyberspace “revolution”. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Molyneux, L. (2015) ‘What journalists retweet: Opinion, humor, and brand development on twitter’, Journalism (London, England), 16(7), pp. 920-935. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914550135

Molyneux, L. and Mourão, R. R. (2019) ‘Political journalists’ normalization of Twitter: Interaction and new affordances’, Journalism Studies (London, England), 20(2), pp. 248-266. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1370978

Molyneux, L., Mourão, R.R and Coddington, M. (2016) ‘U.S. Political Journalists’ Use of Twitter: Lessons from 2012 and a Look Ahead’, in R.C. Davis, C. Holtz-Bacha, & M.R. Just (Eds.), Twitter and Elections around the World: Campaigning in 140 Characters or Less. New York: Routledge, pp. 43-56.

Mondragon, V. M., García-Díaz, V., Porcel, C. and Crespo, R. G. (2017) ‘Adaptive contents for interactive TV guided by machine learning based on predictive sentiment analysis of data’. Soft Computing (Berlin, Germany), 22(8), pp. 2731-2752. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2530-x

Mourão, R. R. (2015) ‘The boys on the timeline: Political journalists’ use of Twitter for building interpretive communities’, Journalism (London, England), 16(8), pp. 1107-1123. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914552268

Mourão, R., Diehl, T. and Vasudevan, K. (2016). ‘I love big bird: How journalists tweeted humor during the 2012 presidential debates’. Digital Journalism, 4(2), pp. 211-228. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1006861

Pariser, E. (2012) The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. London: Penguin Books.

Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (2011) The SAGE handbook of social network analysis. London: SAGE.

Singer, J. B. (2005) ‘The political j-blogger: ‘Normalizing’ a new media form to fit old norms and practices’, Journalism (London, England), 6(2), pp. 173-198. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905051009

Singer, J. B. (2014) ‘User-generated visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space’, New Media & Society, 16(1), pp. 55-73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813477833

Stieglitz, S. and Dang-Xuan, L. (2013) ‘Emotions and information diffusion in social media-sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior’, Journal of Management Information Systems, 29(4), pp. 217-248. doi: https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

Stromer-Galley, J. (2014) Presidential campaigning in the internet age. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tandoc, E. C. and Vos, T. P. (2016) ‘The journalist is marketing the news: social media in the gatekeeping process’, Journalism Practice, 10(8), pp. 950-966. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1087811

Vaccari, C., Chadwick, A. and O’Loughlin, B. (2015) ‘Dual screening the political: Media events, social media, and citizen engagement: Dual screening the political’, Journal of Communication, 65(6), pp. 1041-1061. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12187

Verweij, P. and van Noort, E. (2014) ‘Journalists’ Twitter networks, public debates, and relationships in South Africa’, Digital Journalism, 2(1), pp. 98-114. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.850573

Walters, P. (2021) ‘Reclaiming control: How journalists embrace social media logics while defending journalistic values’, Digital Journalism, 1(20). doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1942113

World Bank. (2020) Population, total-Lebanon. World Bank: World Development Indicators. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=LB (Accessed: 20 May 2022).