Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2024, vol. 14, pp. 70–87 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2024.14.5

Unveiling the effects of nonviolent communication training on youth empathy

Aistė Batūraitė-Bunka

Social Integration Center, Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2075-2982

Margarita Jurevičienė

Social Integration Center, Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4831-723X

Gert Skoczowsky-Danielsen

Empathos Partners

------------------------------------------------------

The article is funded according to the project „Peaceful Communication – the Language of Life“ (No LT03-2-SADM-K01-034). The project is funded by the EEA Financial Mechanism Health Programme 2014-2021

------------------------------------------------------

Abstract. Nonviolent communication (NVC) is a model of communication approach, a method, a process, a mindset and a way of life, and was developed by Marshal Rosenberg. NVC offers tools that support the principle of nonviolence and empathic communication. Empathy can be important in promoting pro-environmental behavior (Kansky & Massarani, 2022), and the lack of empathy has been associated with antisocial behavior and reoffending (Bazemore & Stinchcomb, 2004).

The study aims to reveal a self-perceived change in empathy of vulnerable and not vulnerable youth after NVC training.

To conduct the research, a qualitative research methodology was chosen, applying a structured interview survey method. Researchers conducted 10-hour-long NVC trainings for vulnerable and non-vulnerable youth groups and participants were asked open-ended questions in writing. The study demonstrated the feasibility of and relevance to NVC training on (vulnerable) youths‘ empathic communication. Results of the study have revealed the positive effects of intervention on increasing empathy, self-empathy, and efforts to renounce violent communication.

Keywords: Nonviolent communication, empathy, self-empathy, vulnerable youth.

Recieved: 2024-04-18. Accepted: 2024-05-22

Copyright © 2024 Aistė Batūraitė-Bunka, Margarita Jurevičienė, Gert Skoczowsky-Danielsen. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Communication skills play a main role in education. And is always about two or more people actively exchanging their thoughts; if one of them shows signs of disinterest, this should be a clear indicator for the other person not to ask for more attention (Suzić, Marić, & Malešević, 2018).

The type of communication that will be primary and dominant in everyday life, i.e. within a school and in interactions between students as well as between students and teachers, largely depends on the attitude and role of the teacher (Džaferović, 2018) but also on the interest of students in learning about communication, tolerance and successful cooperative relationships and training strategies (Rimm-Kaufman, Baroody, Larsen et al., 2015)

Nowadays, children and young people often use the language of violent communication (Maksimović, Milanović, & Zajić, 2022). These various violence problems show that young people today are less able to feel what others feel (Qudsyi, Trimulyaningsih, Novitasari, & Stueck, 2018). Empathy is defined as the capacity of a person to feel the emotions of others and show compassion as perceived and understand the emotional condition of others (Lazuras, Pyzalski, Barkoukis, & Tsorbatzoidis, 2012). One communication strategy that is effectively used is Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC), which aims to foster connection and understanding through the communication of judgment-free observations, greater recognition of people’s feelings, needs, and values, and requests for specific actions to meet those needs. NVC offers tools and principles that support the principles of nonviolence, empathy, and collaborative communication (Branscomb, 2011). In the process of education, effective communication facilitates students’ understanding of knowledge imparted by teachers (Xinli, Jinsong, & Qiuxia, 2003), and improves interpersonal relationship, and empathy abilities.

Nonviolent Communication and Empathy

Nonviolent communication (NVC) was created in the early 1960s (Rosenberg, 2003), it is a form of communication that assumes people are, by nature, compassionate and share the same basic human needs. NVC is often synonymous with compassionate communication. The concept contains nothing new and all that has been integrated into NVC has been known for centuries with the idea that language and communication skills strengthen our ability to remain human (Roy, 2020).

The main focus, during the implementation of NVC, is placed on language, i.e. how words are used, on the one hand, and listening on the other (Rosenberg, 2003). However, our thinking, our intentions, our assumptions, our use of power and our nonverbal language are just as important, as they highly influence how we listen, express ourselves and interdependently engage with ourselves and with others (Finkelstein, 2016).

The goal of NVC is to establish genuine connections between people, including opponents, based on the assumption that – when sincere communication between rival parties has been established – the dispute will be transformed. This assumption is useful within the NVC process because it allows for communication to be directed towards meeting a relatable human need, which can facilitate interpersonal connection (Rosenberg, 2003).

The NVC includes a four-step process: observation – noting what actions were taken in the conflictual situation. For example (Epinat-Duclos, Foncelle, Quesque et al., 2021), I do not observe that this little boy is nasty, as I can only observe that he ate the cake that was in another child’s hand; therefore, it is only my interpretation that “he is nasty. Second, is feelings – identifying the feelings (of each person involved) linked to those actions. The third step is to take responsibility for our feelings by connecting them to our deep needs. For example, I may feel sad because I imagine the other child is hungry, and a need for equity is acknowledged in me right now, or I may feel angry because a need for justice is alive in me, or I may feel amused because I connect the child’s innocence to my need for lightness. The interesting idea about needs is that we should ensure that they reflect universally shared needs (e.g., a need for water, movement, intimacy, support, serenity, or expression) (Epinat-Duclos, Foncelle, Quesque, et al., 2021). And the unique part of NVC is to prolong this process by expressing a request. A request – the expression of a request, specifying the actions each party wants the other to perform, to support the fulfillment of their needs (Rosenberg, 2003). Indeed, these four processes constitute the ground-breaking formula of Rosenberg (2003) to foster peace and compassion at both personal and social levels and are the base cell of the entire nonviolent communication process.

In addition, NVC systematically illuminates characteristics occurring inside us or between individuals through the empathy process and attempts at empathic communications reflecting the understanding and resonation of human beings (Barrett-Lennard, 1993).

At one level, Nonviolent Communication can be used in all types of relationships, a class discussion, a chat at work, or a civic deliberation in the community, and it also has the potential to permeate a person’s or a community’s entire way of life. Through NVC, individuals can identify and diminish reactive and alienating responses to challenging social situations while increasing their skills in empathic conflict resolution and positive relationship building (Rosenberg, 2005).

NVC is an effective method for enhancing multidimensional empathy (Sung, Kweon, 2022) and seeks to dismantle embedded forms of negative communication and provides a framework for developing an empathic way of communicating with the self and with others (Marlow, Nyamthi, Grajeda, et al., 2011). NVC is that empathy and understanding are shared human needs and the foundation for resolving conflict peacefully (Rosenberg, 2005). The state of empathy, or being empathic, is to perceive the internal frame of reference of another with accuracy and with the emotional components and meanings that pertain thereto as if one were the person, but without ever losing the „as if“ condition (Rogers, 1995). Unlike a debate that puts the parties in collision and conflict, NVC practice promotes empathic listening that enables people to fully engage in the process of communication (Friesem & Friesem, 2021). The lack of empathy has been associated with antisocial behavior and reoffending (Bazemore & Stinchcomb, 2004).

Theoretical and empirical work to date suggests that empathy can be important in promoting pro-environmental behavior (Kansky & Maassarani, 2022). NVC seeks to dismantle embedded forms of negative communication and provides a framework for developing an empathetic way of communicating with self and others (Nosek & Durán, 2017).

NVC is taught in schools and prisons, in churches and community centers, and colleges and universities (Latini, 2009). Therefore, used particularly in situations when building relationships is key (Cox &Dannahy, 2005). Koegel (2002) argues that NVC techniques can be utilized to enhance an educational style called partnership education. This is a versatile approach consisting of principles and techniques of communication that could be applied to any population and in any setting (Vazhappilly & Reyes, ٢٠١٧).

Research that has been done related to empathy intervention includes interpersonal skills training, narrative strategy (such as drama, theatre, literature, and writing) (Qudsyi, Trimulyaningsih, Novitasari, & Stueck, 2018); experiential learning, problem-based learning, communication skill training, empathy focus training (Batt-Rawden, Chisolm, Anton & Flickinger, 2013) and reflective writing (Qudsyi, Trimulyaningsih, Novitasari, & Stueck, 2018).

This study aims to reveal a self-perceived change in empathy of vulnerable and not vulnerable youth after NVC training.

Methodology

Research methodology and data collection method. To conduct the research, a qualitative research methodology was chosen, applying a structured interview survey method. 118 youth have participated in the research, which consists of four stages:

1) Preparation for the research. Researchers were trained by certified NVC trainer Gert Skoczowsky-Danielsen (Norway) and participated for 2 years in NVC training.

2) The pilot study was implemented to test the prepared NVC program for Lithuanian youth. 25 vulnerable youth (5 groups) were participating in this study. Under the guidance and supervision of a certified trainer pilot NVC trainings for vulnerable youth have been completed by researchers.

3) Researchers conduct NVC trainings of 10 hours duration for youth groups consisting of 5-11 persons. Four to five training sessions of two-three-hour duration were conducted for each group.

4) After NVC training participants filled out questionnaires with 81 closed-ended and 4 open ended-questions. In this article, we will only present the results from the structured interview, which consists of 3 demographic data questions and 4 open-ended questions. Qualitative research methodology using open-ended questions helped informants to express their experiences openly.

The questionnaire included these questions: what have you learned by participating in NVC training? What NVC training helped you to understand? Did your communication change after NVC training? If yes, how has it changed? What you could apply in communication from NVC training?

Data processing method. The informants’ answers were processed by applying the content analysis method. The structured interview texts were divided into meaningful units – categories and subcategories (themes), to reveal youths’ self-perceived change in communication after NVC training. The article exclusively presents and analyses responses solely from participants who took part in the main study of the structural interview.

The survey sample. A total of 143 (aged from 14 to 18) youth from Siauliai City county (7 towns) and different institutions (gymnasiums, child care homes, socialization center for youth, etc.) were participating in NVC trainings. 25 vulnerable youths participated in the pilot study, and 118 – in the main study. However, 54 youth who participated in the main study gave feedback and answered open-ended questions in writing. 87 vulnerable youth (36 girls and 51 boys) and 31 youth (24 girls and 7 boys) from gymnasiums were participating in the main study. Vulnerable youth were selected based on criteria such as delinquent behavior, emotional and behavioral problems, low learning motivation, and mild intellectual disability. Youth were students from gymnasiums not having learning and behavior problems.

Research ethics. Throughout the research, adherence to the principles of voluntary participation, anonymity, confidentiality, and privacy was diligently observed. Participants had the liberty to decline continued participation in the research and to disclose personal information about themselves as much as they wanted. To uphold the principle of ensuring the participation of both vulnerable and non-vulnerable youth, both verbal and written consents were acquired. Furthermore, to safeguard the anonymity of the research participants, identifiers such as names of the institutions and schools where the research was conducted, as well as the individual names of the participants, were omitted during the data analysis.

Findings

Within the context of an extensive research framework, and post-comprehensive data analysis, this article adopts a focused presentation, centering on the observable evolution in participant empathy after NVC training. In recognition of the multifaced nature of empathy and the nuanced alterations within, our approach entails a systematic exposition of distinct categories, each meticulously delineated through detailed subcategories.

From Judgement to Observation. The four-step model in Nonviolent communication begins with observation and “it involves the capacity to differentiate what we are hearing, seeing and remembering from how we are evaluating what we are hearing, seeing, and remembering.” (Latini, 2009, p. 22). According to the author, “moralistic judgments are static assessments of others or ourselves, value judgments identify whether or not particular actions are constant with that which matters most to us” (Latini, 2009, p. 23). Observation lets us avoid moralistic judgments about others and leads to interpersonal connection. Observation is directly related to empathy because to be able to feel and try to understand another individual firstly, we need to give up prejudice and judgements.

“Differentiating my observation from my evaluation” (see Table 1) shows that NVC training helped participants to recognize and understand the forms of violent communication resulting in blocking empathy as well as being able to separate them from observation:

“I started noticing a “jackal” in my language, whenever I judge or criticize someone. I hope these features will diminish over time” or “I have begun noticing more violent communication traits both in my interactions and those of others, including tendencies such as offering unsolicited advice, comparisons, and providing compliments.”

Table 1.

From Judgement to Observation

|

Themes |

Youth* |

Examples of statements from the interview |

|

Differentiating my observation from my evaluation |

Y |

I started noticing a “jackal” in my language, whenever I judge or criticize someone. I hope these features will diminish over time. (J5) A lot of people use violent communication in their everyday language. (D4) To notice violence (D8) I have begun noticing more violent communication traits both in my interactions and those of others, including tendencies such as offering unsolicited advice, comparisons, and providing compliments. (D9) |

|

VY |

What is violent communication? (JR13) |

|

|

Decreased self-criticism |

Y |

I learned to stop judging myself. (SD1) |

|

Decreased criticism, judgment, evaluation, and expectation |

Y |

I try to refrain from criticizing others around me. (SD1) I try to avoid harboring expectations toward others, I refrain from using words such as „never“, and „always“. (J2) I learned to stop rating and say, “I like” (J3) I learned to abstain from making judgments, opting instead to perceive situations, maintain factual discourse, and refrain from personal attacks. (D9) |

|

I have come to recognize that my style of communication is „jackal“ – I assert my correctness and elevate myself above others. The meeting regarding compliments opened my eyes to comparisons. (D9) It’s no longer clear who is right. D8) |

||

|

VY |

Respect. It is important to respect others. (JR14) Tranquillity, peace, joy (JR21) Peace, tranquillity (JR21) |

|

|

Efforts to renounce violent communication |

Y |

It isn‘t easy to adapt to „giraffe“ language, however I will try. (D9) It is different from the communication we use. (SD2) I will try to lean towards the giraffe side in jackal society. (SD3) |

|

VY |

<...> Peaceful communication (JR5) Peaceful communication, no condemning others. No judgments, no condemnation. (JR5) This way I feel more pleasant. (JR6) <...> I am more pleasant. (JR13) |

|

|

Increased interpersonal connection |

Y |

Provoking conflict and emerging victorious won’t foster a sense of well-being; instead, it will erode the interpersonal connection with the other party involved. (SD3) How to communicate to foster a connection with another individual. (SD9) I comprehended the underlying reasons prompting individuals to turn away from one another. (SD9) I have acquired better knowledge on how to start a conversation and I start a conversation more often. (D1) My relationship with myself and others has changed. (D2) |

|

VY |

How to foster a connection. (JR8) |

Note. *Y – youth; VY – vulnerable youth.

Most discussions had arisen from observations that static language such as compliments (e.g. “you are beautiful” or “you are smart”) may be accepted as a subtle form of violence. Many individuals are accustomed to delivering compliments in an evaluative manner, under the impression that it will serve as support, encouraging others to continue to persist in their actions and endeavors. Youth, especially those with high grade point averages (GPA), had noticed that assessments such as “You are smart” stress them out because of the arisen fear of losing their “status”. Students who hear other students being praised for their intelligence experience frustration, as such commendations may lead them to perceive themselves as lesser intellect. Consequently, as delineated by Rosenberg, the act of comparison blocks the interpersonal connection and is considered a form of violence.

“Decreased self-criticism” signifies that NVC trainings for youths helped to decrease self-criticism, and stop blaming themselves. However, this subcategory supporting statements in the answers from vulnerable youth were not found. Vulnerable youth receive the most moralistic judgment from the surrounding environment. To form a different attitude towards oneself, additional models of innervation are needed, which were not applied during the research.

“Decreased criticism, judgment, evaluation, expectation” shows that youth started noticing criticism and moralistic judgment in their own and other individuals’ language.

“I learned to abstain from making judgments, opting instead to perceive situations, maintain factual discourse, and refrain from personal attacks.”

Vulnerable youth indicated that they started showing more respect towards others.

“Efforts to renounce violent communication” reveals that for youth it is difficult to accept changes and change the style of communication, even if they are highly motivated. Nonviolent communication deviates from the typical practices observed within society. Therefore, youth may express concerns regarding the application and integration of newly acquired knowledge, understanding, and skills. Also, this subcategory shows that vulnerable youth accept NVC which they link to peace and enjoyment.

“Increased interpersonal connection” reveals how participants derive meaning from acquired knowledge. NVC training helped participants discover the reasons why previous communication was not as effective as expected:

“I comprehended the underlying reasons prompting individuals to turn away from one another” or “Provoking conflict and emerging victorious won’t foster a sense of well-being; instead, it will erode the interpersonal connection with the other party involved.”

Participants learned how to foster a connection better and how to maintain the interpersonal connection with other individuals.

Understanding Self-Empathy. The majority of youth, participating in NVC training, heard about empathy and they would link it to understanding other individuals’ situations and feelings. The concept of empathy in NVC training Rosenberg extends to Self-Empathy. Self-Empathy requires you to notice and recognize what is happening in you, and to understand your feelings and needs. It means treating ourselves with compassion, and understanding, even when we face our “mistakes” or troubles. Self-compassion or self-empathy is defined as “being open to and moved by one’s suffering, experiencing feelings of caring and kindness toward oneself, taking an understanding, non-judgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures, and recognizing that one’s experience is part of the common human experience” (Neff, 2016). Self-compassion is linked with needs of competence, connectedness, independence, and self-determination (Magnus et al. 2010).

Self-empathy concept for participants is a new concept. The acknowledgment and acceptance of one’s feelings and needs are often perceived as egoistical, subsequently followed by feelings of guilt and dissatisfaction.

Table 2.

Increased Self-Empathy

|

Themes |

Youth* |

Examples of statements from the interview |

|

Identifying my feelings and needs |

Y |

Helped me comprehend my emotions and needs. (SD4) Facilitated the recognition of needs and understanding the underlying reasons for my actions. (D3) |

|

VY |

Recognition of emotions and needs (JR5) |

|

|

Understanding the importance of needs |

Y |

To effectively help another individual, it is important to maintain personal well-being. (SD7) The needs of every individual hold significance, including my own. (J5) |

|

Honest Expression |

Y |

I have started expressing my feelings and needs, at least I will try doing so. (J3) |

|

VY |

Expressing needs, expressing feelings. (JR12) The change lies in being able to express myself more openly (JR22) |

Note. *Y – youth; VY – vulnerable youth.

During NVC trainings participants learned to recognize and understand their feelings and needs, to express themselves honestly. The research results have shown that NVC training for participants helped to better identify their feelings and needs and that there are needs underlying each action (see Table 2):

“Facilitated the recognition of needs and understanding of the underlying reasons for my actions.”

Youth understood the importance of acknowledging one’s own needs, as visibly demonstrated in the following answers, such as:

„To effectively help another individual, it is important to maintain a personal well-being.”

For the majority of participants, the concept of understanding and accepting their own needs is rather new. According to the youth the concept of understanding that their own needs are as important as the needs of others, allows them to develop a better and more positive connection with themselves. However, the answers of vulnerable youth didn’t contain arguments confirming the following „Understanding the importance of needs”.

„Honest Expression“ shows that participants have noticed being able to express their feelings and needs more freely while communicating with others. The majority of participants during NVC training had doubts, and questions arose about how to apply the models offered by NVC in their everyday communication. According to them, this style of communication is unusual because “no one communicates in this way”, and “others might not understand”. On the other hand, they agreed that a new outlook on feelings and needs may contribute to creating a positive interpersonal connection with other individuals.

NVC increased Empathy. Results of this study have revealed positive effects on three components of empathy: empathic reception, identifying others’ needs and feelings, and the ability to listen empathically. Empathy usually refers to „the ability to understand or share others’ feelings and to respond with appropriate emotions” (Baron-Cohen 2011). Empathy starts with observing the situation without judgment, evaluation, or criticism.

Table 3.

Increased Empathy

|

Themes |

Youth* |

Examples of statements from the interview |

|

Empathic Reception |

Y |

There is invariably a rational reasoning underlying everyone’s actions (SD6) It is erroneous to hastily judge someone without knowing the entire situation (SD4) I refrain from hastily criticizing individuals and instead, I ask myself what the reasoning behind their actions is. (SD8) |

|

VY |

Yes, understanding others. (JR14) There has been a slight change in the way I perceive others. (JR17) |

|

|

Identifying others’ feelings and needs |

Y |

I try to enhance my understanding of others‘ needs without raising expectations for them. (SD1) Consider other individuals’ needs and look at the situation from a different perspective. (SD8) What is empathy, how human feelings are formed, and what are the needs of a person? (J4) |

|

VY |

What I feel and what others feel (JR3) Understand others. I better understand other people‘s feelings. Feelings and needs. (JR23) |

|

|

Listening empathically |

Y |

I will adopt to listening empathically. (SD2) Listening to others while fostering empathy towards myself and others (SD3) Listening to others, recognition of needs and empathy, overview of the situation (D1) |

|

VY |

To listen and to help people (JR4) |

Note. *Y – youth; VY – vulnerable youth.

The majority of participants indicated that responding defensively, either by attacking others or oneself, is perceived as easier, and such behavior is often construed as a manifestation of disrespect towards them. „Emphatic Reception“ shows, that participants learned to perceive situations by trying to understand others (see Table 3).

“There is invariably a rational reasoning underlying everyone’s actions” or “I refrain hastily criticizing individuals and instead I ask myself what the reasoning behind their actions is.”

The act of observation without judgment fosters mutual connection. However, refraining from judgment presents a formidable challenge. All societal frameworks such as social spheres, education, finance, law, etc. are based on the principle of punishments and rewards. This creates a coercive mechanism and diminishes inner motivation. NVC is the philosophy of life, that’s why changing the perception entirely and understanding the point of peaceful communication in 10 hours is impossible. Additionally, during the training, the majority of participants noticed that NVC should be adapted by parents and teachers. Because they are the first ones to convey lifestyle and communication experiences.

According to Rosenberg empathy is an attempt to understand the feelings and needs of another individual. The capacity to identify and express feelings requires that we differentiate feelings from thoughts. Most of us use the word feel to express opinions, evaluations, and preconceived notions which can be biased or judgmental. Therefore, during NVC trainings participants are prompted to divert their attention towards observing feelings and needs. „Identifying others’ feelings and needs” shows that revealing one’s own needs which do not necessarily have to be met, because expectations are related to demand and reduction of freedom of choice:

“I try to enhance my understanding of others’ needs without raising expectations upon them.”

The participants have noted that NVC training has helped them better identify the feelings and needs of other people.

Participants were acquainted with delineations of empathy and its absence. Additionally, it was discussed how they usually tend to listen to another individual. The majority of participants thought they had the answers to the other person problem and were quick to give advice. After training they discovered that people want to be heard more instead of wanting advice. “Listening Empathically” reveals that they learnt new ways of interacting with others. In developing a capacity to listen, participants learned to overview the situation and to notice the feelings and needs of others. Also, it helped them to see that they could connect more meaningfully with the other person.

Discussion

Empathy has a long history, dating back to the eighteenth century, and, subsequently, in psychology, psychoanalysis, and therapy (Tudor, 2011). One of the earliest psychologists to define the term “empathy” in a manner that closely aligns with its modern interpretation was Carl Rogers (Rogers, 1951). Rogers (1959) defined empathic understanding in this way: “To perceive the internal frame of reference of another with accuracy, and with the emotional components and meanings which pertain thereto, as if one were the other person, but without ever losing the ‘as if’ condition” (p. 210). Rogers (1980) stated that „True empathy is always free of any evaluative or diagnostic quality” (p. 154). The author has stated that a client who feels herself or himself understood and accepted feels calmer, and more related to another human being. Rosenberg, in his analysis of empathy, primarily relied on the works of Carl Rogers and elucidated the significance of empathy as a multifaceted construct.

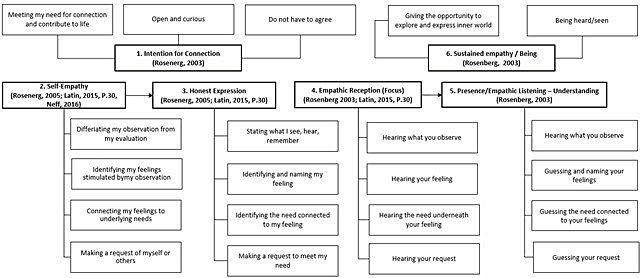

To discern the significance, identify potential problem areas, and acknowledge the limitations inherent in this study, we initiate by presenting the multifaced nature of the concept of empathy (refer to Figure 1), which we complied based on the works of Marshal Rosenberg and other certified NVC trainers, as well as insights and materials garnered from NVC training sessions.

According to Rosenberg (2003), empathy consists of 6 components: intention for connection, self-empathy, honest expression, empathic reception (focus), presence/empathic listening, and sustained empathy/being. As delineated by Rosenberg (2003) empathy is a respectful understanding of what other individuals are experiencing; empathy transcends mere auditory perception; it encompasses an understanding of others’ perspectives. Hence, empathy initiates with empathic reception – a practice involving attentive listening to discern others’ observations, feelings, needs, and requests. Empathic reception exchanges can help build a sense of trust and connection through interaction with others (Han, Kim, Lee, et al. 2019).

NVC methodology teaches us to express our understanding of others in four steps, called empathic listening. As posited by Rosenberg (2003), before directing attention toward solutions, it is important to facilitate the expression of the individual, as attending to their requests in a rush may create the impression that we are eager to dismiss the interlocutor promptly and solve their problem. Therefore, empathy necessitates an additional component – sustained empathy/being – a respectful understanding of what others are experiencing. Instead of offering empathy, we often have a strong urge to give advice or reassurance and to explain our position or feelings. However, calls upon us to empty our minds and listen to others with our whole being.

For empathy to be sincere, according to Rosenberg (2005), intention for connection is highly important. People seek assurance that, when you engage in listening, you are first fulfilling your own need for connection, communicating with genuine curiosity. This does not entail agreement with every viewpoint expressed, but rather the aim to comprehend the perspectives and experiences of other individuals. Consequently, Rosenberg introduces the term “self-empathy”, which is conveyed to another individual through honest expression. Intention for connection and sustained empathy hinges upon an open and sincere willingness to attentively listen to the other party. Moreover, self-empathy, honest expression, empathic reception, and empathic listening require individuals to adeptly accept and convey the information they receive.

Findings from the structured interview analyses demonstrated the positive impact of NVC on the ability to empathize with oneself and others, that is to say, participants gained skills in 2-5 empathy components (refer to Figure 1). The participants demonstrated proficiency in identifying feelings and needs, thereby emphasizing the importance of needs in human existence. Upon comparing the findings of the study conducted among vulnerable and non-vulnerable youth, similar alterations in empathy are observed. Consequently, NVC trainings exhibit a positive impact on the empathy of both groups of youth. However, within the responses provided by vulnerable youth, statements reflecting reduced self-criticism and comprehension of the significance of needs were not found.

Figure 1.

NVC Empathy Model and Four Basic Skills according to Rosenberg

Similar results are found in other research. In the research of Nosek, Gifford & Kobert (2014) qualitative and quantitative results reveal an increase in empathy post-NVC training. The authors studied nursing students’ empathy after NVC training and found that they take on more responsibilities and begin to focus more on tasks. Nursing students’ stories shared in the study demonstrated ways that they incorporated NVC to arrive at new understandings of others’ emotions and needs, which resulted in the de-escalation of tense situations, and calmness in others, as well as their sense of efficacy in their roles as friends, teachers, and nurses. Also, Marlow, Nyamthi, Grajeda, et al. (2011) study demonstrated a significant increase in empathy levels in a group of male parolees enrolled in substance abuse treatment.

The findings of this study indicate that participants successfully acquired proficiency in the first step of NVC, namely the ability to differentiate between judgments and observations from 2 to 5 (refer to Figure 1) empathy component. For the majority of participants communication forms often resulting in blocked connections were new. They started noticing on a more frequent basis judgements, criticism, and evaluations in the language of one’s own and others’. However, in the qualitative analysis of responses among participants, we still found self-criticism, self, and others evaluation and judgment statements (e.g., “How to communicate accurately”).

According to Rosenberg (2005), the principles of NVC can be applied to all types of relationships, including those within families, workplaces, and schools, as well as across different cultures. Due to its universality – participants are taught to understand feelings, and needs, which are inherent to every individual – NVC is successfully implemented in over 60 countries worldwide. When applying NVC within the Lithuanian context, certain challenges in finding equivalent translations were encountered. For instance, there is no direct translation in Lithuanian for the phrase “are you willing”. Consequently, to ask about another person’s needs, one must consider the context of the conversation before selecting an appropriate word.

Participants learned three steps of NVC (observation, to identify feelings and needs), due to lack of time, less time was devoted to attaining proficiency in the fourth step of NVC (making requests). The research limitation highlights that while participants acquired proficiency in the NVC steps, the study does not provide insights into the extent to which these skills were internalized, the durability of the acquired knowledge, or the participants’ inclination to apply these skills in real-world scenarios. Additionally, in this study, certain participants expressed skepticism regarding the usage of NVC in their daily lives, citing its uncommon usage within their social circle. They expressed concerns regarding the potential misunderstanding of such communication methods by others. It is essential to acknowledge that to attain the full effectiveness of the NVC program, the youth environment necessitates the NVC training regimen, involving family members, educators, and even friends.

The participants of the research revealed the active involvement of parents in the importance of education, as their upbringing significantly influences life and communication styles. To achieve long-term changes in social relations, NVC lessons could be integrated into the general education curriculum, e.g. Life Skills Program, with universities later enhancing students’ competencies. Additionally, specialists from educational institutions – such as social pedagogues, special educators, psychologists, and social workers – working with young people could benefit from learning NVC principles. Moreover, in Marlow, Nyamthi, Grajeda, et al. (2011) research, we noticed that while some commented that NVC would not be effective for daily life, the majority felt that empathic communication skills applied to their interpersonal relationships in all areas of their lives. On the other hand, research works by other authors show, that persons who have participated in NVC training tend to apply the acquired knowledge later in life. For example, the mentioned authors claim that most participants immediately employed the skills they learned during the intervention in their personal lives with positive effects. Moreover, the majority of participants in this study exhibited a keen interest in continuing their NVC training. During the research, it was observed that NVC functions optimally when individuals communicate authentically, expressing their genuine feelings and needs.

The study observed the interventional effects of NVC training, allowing participants to feel peace, joy, gratitude, and curiosity in subsequent sessions. In the initial training sessions, 19% of participants reported feelings of sadness, attributable to the emergence of long-suppressed emotional experiences. Occasionally, the emotions elicited necessitated additional individual support; therefore, the training must be conducted by certified NVC trainers or specialists who possess the skills to apply empathic listening and manage a wide range of situations effectively.

NVC has been increasingly recognized as a potentially beneficial approach that could promote empathy, resolve conflicts, and improve psychosocial well-being (Cheung, Cheng & Fung, 2022). Gottman (2000) asserts that NVC aids in recognizing and naming feelings, listening with empathy, resolving conflicts, and selecting appropriate solutions. Summarizing the results of a systemic review, it can be inferred that NVC is an effective tool for altering social behavior patterns in individuals and groups. It enhances the empathy of communicators, increases sensitivity to both personal and others’ needs and experiences, and develops the ability to verbalize emotions, cope empathically with stress, and resolve conflicts (Visakavičiūtė & Bandzevičienė, 2018). The education of empathy facilitates the establishment of better interpersonal relationships and plays a crucial role in modifying human behavior, potentially reducing crime occurrences. An analysis of literature conducted by Visakavičiūtė, Bandzevičienė (2018) revealed that the more hours individuals serving sentences in prisons spent participating in NVC training, the less likely they were reoffended. Out of the 85 convicts who participated in NVC training, 188 (21%) returned to prison during the ten-year study period. Participants on average spent 35,2 hours in NVC training. Notably, those who reoffended had spent significantly fewer hours in training compared to those who remained at large (Visakavičiūtė & Bandzevičienė, 2018).

And finally, these findings once more support the idea, that empathy can be learned. In this instance, the duration of NVC training holds significant importance, as research highlights a positive correlation between intervention duration and observed outcomes.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated the feasibility and relevance of NVCs training for (vulnerable) youths’ empathic communication.

Results of the study have revealed the positive effects of the intervention on increasing empathy, self-empathy, and efforts to renounce violent communication. However, 10-hour sessions are not enough for significant changes in participants’ communication. NVC training allows a better understanding of interpersonal connection, and NVC skills development requires more practice.

References

Barrett-Lennard, G.F. (1993). The phases and focus of empathy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 66, 3–14. https:// doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01722.x

Baron-Cohen, S. (2011). The science of evil: on empathy and the origins of cruelty. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Batt‐Rawden, S.A., Chisolm, M.S., Anton, B., & Flickinger, T.E. (2013). Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1171–1177. https://doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3

Bazemore, G., & Stinchcomb, J. (2004). A civic engagement model of re-entry: Involving community through service and restorative justice. Federal Probation,68(2), 1-14.

Branscomb, J. (2011). Summative Evaluation of A Workshop in Collaborative Communication. Thesis. Emory University. COVID-19 pandemic: Nonviolent Communication. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 13(3), 133-136. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2021- 13-3-11

Cheung, T.T.; Cheng, C. M-H., & Fung, H. W. (2022). Reliability and Validity of a Novel Measure of Nonviolent Communication Behaviors. Research on Social Work Practice. 33(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315221128595

Cox, E., & Dannahy, P. (2005). The value of openness in e-relationships: Using Nonviolent Communication to guide online coaching and mentoring. International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring, 3(1), 39–51.

Džaferović, M. (2018). The effects of implementing a program of nonviolent communication on the causes and frequency of conflicts among students, Teme-Časopis za Društvene Nauke, 42(1), 57-74.

Epinat-Duclos J., Foncelle A., Quesque F., Chabanat E., Duguet A., Van der Henst J. B., & Rossetti Y. (2021). Does nonviolent communication education improve empathy in French medical students? International Journal of Medical Education, 12, 205–218. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.615e.c507

Finkelstein, J. (2016). What is Nonviolent Communication? Marshall‘s Art. Chobo-ji. https://choboji.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/nvc2.pdf

Friesem, Y., & Friesem, E. (2021). The secret sauce of online community of practice during COVID-19 pandemic: Nonviolent Communication. Journal of Media Literacy Education 13(3), 133-136. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2021-13-3-11

Han, J.Y, Kim, E., Lee, Y.I., Shan, D.V., & Gustafson, D.H. (2019). A Longitudinal Investigation of Empathic Exchanges in Online Cancer Support Groups: Message Reception and Expression Effects on Patients’ Psychosocial Health Outcomes. Journal of Health Communication, 615-623. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2019.1644401

Kansky R., & Maassarani, T. (2022). Teaching nonviolent communication to increase empathy between people and toward wildlife to promote human-wildlife coexistence. Conservation Letters, 15(1). https:// doi.org/10.1111/conl.12862

Koegel, R. (2002). Nonviolent communication and partnership education. Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice, 15(3), 2-4.

Latini, T. F. (2009). Nonviolent communication: A humanizing ecclesial and educational practice. Journal of Education and Christian Belief, 13(1), 19-31.

Lazuras, L., Pyzalski, J., Barkoukis, V., & Tsorbatzoidis, H. (2012). Empathy and moral disengagement in adolescent cyberbullying: implications for educational intervention and pedagogical practice. Studia Edukacyjne, 23, 57-69.

Magnus, C.M.R., Kent, C., Kowalski, F., & Tara-Leigh F. (2010). The role of self-compassion in women’s self-determined motives to exercise and exercise-related outcomes. Self and Identity ٩, ٣٦٣–٨٢.

Magnus, C.M.R., Kowalski, K.C., & McHugh, T.L.F. (2010). The role of self-compassion in women’s self-determined motives to exercise and exercise-related outcomes. Self and Identity, 9, 363–382.

Maksimović, J., Milanović, N.M., & Zajić, J.O. (2022). The role of action research in the prevention of violent communication of students, Research in Pedagogy, 12, 216-225. https://doi.org/10.5937/IstrPed2201216M

Marlow, E., Nyamathi, A., Grajeda, W. T., Bailey, N., Weber, A., & Younger, J. (2011). Nonviolent Communication Training and Empathy in Male Parolees. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 18(1), 8–19. https://doi:10.1177/1078345811420979

Neff, K. D. (2016). “The Self-Compassion Scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion”: Erratum. Mindfulness, 7(4), 1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0560-6

Nosek M., & Durán M. (2017). Increasing empathy and conflict resolution skills through nonviolent communication (NVC) training in Latino adults and youth. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 11(3), 275-283. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2017.0032

Nosek M., Gifford E. J., & Kober B. (2014). Nonviolent Communication Training Increases Empathy in Baccalaureate Nursing Students: A Mixed Method Study. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 4(10), 1-15.

Qudsyi, H., Trimulyaningsih, N., Novitasari, R., & Stueck, M. (2018). Developing model of nonviolent communication among children in Yogyakarta. Proceeding of International Conference on Child Friendly Education, 149-160.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Baroody, A. E., Larsen, R. A., Curby, T. W., & Abry, T. (2015). To what extent do teacher-student interaction quality and student gender contribute to fifth graders’ engagement in mathematics learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 170-185. https://doi: 10.1037/a0037252

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy. London, England: Constable.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science: Formulation of the person and the social context (pp. 184-256). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, C.R. (1995). A Way of Being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Roy, S. (2020). Role of Nonviolent Communication in our Daily Life, Journal of Mass Communication, 17, 1-2, 24-27.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2003). Nonviolent communication: A language of life (٢nd ed.). Encinitas, CA: PuddleDancer.

Sung, J., & Kweon, Y. (2022). Effects of a Nonviolent Communication-Based Empathy Education Program for Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Pilot Study, Nursing Reports, 12(4), 824-835. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12040080

Suzić, N., Marić, T., & Malešević, D. (2018). Effects of nonviolent communication training program on elementary school children. Arctic, 71(8), 35 – 62.

Tudor, K. (2011). Understanding empathy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 41(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215371104100107

Vazhappilly, J. J., & Reyes, M. E. S. (2017). Non-Violent Communication and marital relationship: Efficacy of ‘Emotion-Focused Couples’ Communication Program among Filipino couples. Psychological Studies, 62(3), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-017-0420-z

Visakavičiūtė, E., & Bandzevičienė, R. (2019). Impact of the Nonviolent Communication intervention program on the social behavior of the participants: Overview of the systemic research analysis. Socialinis darbas, 17(1), 102-121. https://doi.org/10.13165/SD-19-17-1-07

Xinli, Z., Jinsong, Y., & Qiuxia, L. (2003). Nonviolent Communication Strategies in Education from the Perspective of Illocutionary Acts, Curriculum and Teaching Methodology, 6(9), 105-112. https:/doi.org/10.23977/curtm.2023.060915