Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2023, vol. 13, pp. 148–166 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2023.13.19

Social-Educational Factors of Children’s Citizenship Education in Basic School: the Context of Lithuania

Daiva Malinauskienė

Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy, Lithuania

daiva.malinauskiene@sa.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9532-2840

Asta Vaitkevičienė

Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy, Lithuania

asta.vaitkeviciene@sa.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9834-0959

Nijolė Bražienė

Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy, Lithuania

nijole.braziene@sa.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-9689-0882

Asta Širiakovienė

Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy, Lithuania

asta.siriakoviene@sa.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7444-8612

Erika Masiliauskienė

Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy, Lithuania

erika.masiliauskiene@sa.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0903-5886

Abstract. Citizenship education is a relevant issue of education and international policy in many countries, including Lithuania, especially due to the current tense geopolitical situation. In 2022-2023, after updating general education curricula, citizenship education competence is included in all subjects of general education. According to the updated Fundamentals of Citizenship programme for grades 9–10, students can develop citizenship competences by participating in nonformal education and engaging in other activities related to citizenship education. To achieve the aim of the research presented in the article – to analyze the social-educational factors of children’s citizenship education in basic school – an empirical study was carried out, for which the Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education by Valuckienė et al. (2017) was used. The study made it possible to distinguish the social-educational factors important for citizenship education: the child’s trust in the school staff, the child’s relationship with community events, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, the child’s interest in news and the child’s participation in school self-government. The results of the empirical study confirmed the hypotheses: 1) respect for the child’s opinion is moderately positively related to the child’s involvement in the life of the school community, participation in school self-government and 2) adults’ respect for the child’s opinion is weakly positively related to the child’s trust in the school staff.

Keywords: children’s citizenship education, social-educational factors, basic school.

Introduction

Referring to the European Education and Culture Executive Agency report (2018), “[e]ducation is intrinsically connected to the development and growth of individuals within a social context. All forms of responsible education are beneficial not only to individuals themselves, but also to society as a whole. Citizenship education, however, has a special connection with the welfare of society and its institutions” (p. 4). In recent decades, citizenship education has been one of the most relevant issues of education policy in many countries, including Lithuania, and is analyzed from various aspects in the works of researchers. For example, according to James & Davison (2000), for children to be able to act critically in value discourses and thus become informed and ethically empowered and active citizens, social literacy is both a prerequisite for and an essential requirement of citizenship education. It involves learning a series of social skills and developing a social knowledge base from which to understand and interpret the range of social issues which citizens must address in their lives. Schugurensky & Myers (2008) presented seven proposals for twenty-first century citizenship education: from passive to active citizenship, from national citizenship to planetary/ecological citizenship, from recognizing cultural diversity to fostering intercultural societies, from preparation for the public sphere to inclusiveness, from fundamentalism to peace-building, from school-based citizenship to learning communities, from formal to substantive democratic citizenship. Gürkan & Doğanay (2020) aimed to investigate the factors related to school, environment, teacher, student, and programme that affect citizenship education according to the opinions and experiences of secondary school teachers. The results of the study show that both informal and formal education are thought to be effective in citizenship education. Citizenship education is affected positively in terms of multiculturalism, upper socio-economic level, the family’s good education, a strong physical infrastructure, media, peer groups, thinking competence, learning motivation, effective teaching, positive role model teacher, and supporting thinking through the curriculum. Cleovoulou (2021), bringing to the fore the most common questions teachers have about what citizenship education is, why to teach it and how to teach it, explained the perspectives of citizenship education in primary school in order to strengthen civic awareness and a sense of responsible and active citizenship. The attention of researchers is drawn to the role of the school in developing citizenship values in individual countries, e.g., England (Moorse, 2019), China (Chia & Zhao, 2020), South Africa (Wolhuter, Janmaat, van der Walt, & Potgieter, 2020), the Netherlands (Duarte, 2021); a team of authors from different countries (Sant et al., 2022), using case studies from schools in Catalonia, Colombia, England, and Pakistan, inspires the discussion whether citizenship education manifests different conditions of emancipatory education. Generation Z is said to believe in diversity, social justice, and the ability to change the world. Social issues are important to them: health care, mental health, higher education, economic security, civic participation, racial equality, and the environment (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2021), therefore, it is no coincidence that in recent studies in the context of citizenship education, the attention of researchers is focused on the challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing not only empathy, but also compassion, help, providing emotional, social, financial or medical support to others, especially to vulnerable populations (Galea, 2020; Slavich et al., 2022; Saperstein, 2023).

In modern societies, the meaning of citizenship is not only political, but also has a social and cultural dimension. Citizenship is understood as a relationship influenced by identity, social status, cultural preconditions, institutional practices, and a sense of belonging (Olson et al., 2014). As noted in the “Citizenship Education at School in Europe, 2017” research report (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, 2018), citizenship education is a difficult concept to define, because the understanding of what it is and what its goals are differ from country to country, and the concept itself is also variable. Therefore, the aforementioned publication provides a definition that is applied in modern democratic societies: “[c]itizenship education is a subject area which aims to promote harmonious coexistence and foster the mutually beneficial development of individuals and the communities in which they live. In democratic societies, citizenship education supports students in becoming active, informed and responsible citizens, who are willing and able to take responsibility for themselves and for their communities at the national, European and international level” (p. 3). In Lithuania’s Progress Strategy “Lithuania 2030” (2012), it is emphasized that in general education it is necessary to develop creativity, citizenship, and leadership education, because this is the basis of a smart and active community. The development of individual abilities of a person is especially important for the development of creativity and citizenship of a person. In the State Progress Strategy “Lithuania’s Future Vision “Lithuania 2050”” (2023, p. 58), citizenship is associated with commitment to the state, community and unifying values, and the strengthening of culture and community is associated with the cultivation of civic awareness: “an inquisitive, independent and civic personality is the basis of a strong social network in the country,” This basically corresponds to the goals of the general education curricula updated in Lithuania and started to be implemented from 2023-2024, which are intended “to strengthen the development of the individual’s value attitudes, confidence in one’s own abilities, resilience, creativity and citizenship (...). The content of education is based on the consistent and systematic development of human values and competences in order to achieve the well-being of the individual and the progress of society.”

More than a decade ago, Zaleskienė (2014) noticed that although the Lithuanian citizenship education system (aims, objectives, content and methods of its implementation) is being developed taking into account the most advanced educational trends in Europe and the world, civic education in Lithuania is socially engaged, i.e., on the one hand, it is conditioned by the social environment, on the other hand, it itself inspires the creation of a more favorable social environment. The students themselves want to promote integrative civic activities, i.e., to strengthen the links between formal and nonformal education, to connect the subject of the fundamentals of citizenship with civic activity projects, to encourage students to organize events and projects themselves. From today’s perspective, citizenship education in Lithuania, as in other countries, remains relevant, especially due to the current tense geopolitical situation. In 2022-2023, after updating general education curricula, citizenship education competence is included in all subjects of general education. The Fundamentals of Citizenship programme for grades 9–10 has also been updated, students can develop citizenship competences by participating in nonformal education, engaging in activities that are related to citizenship education. According to the report of the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) conducted in 2022 (2023), Lithuanian eighth-graders have the same level of citizenship as their peers in Europe. They discuss political and social issues, what is happening in other countries both with their parents and friends more often than their peers from other countries. Environmental protection is important to eighth-graders – according to a significant number of students, they know how to protect the environment, intend to participate in activities that support environmental protection, understand that both the government of the country and each individual citizen should take care and take responsibility for environmental protection. However, the citizenship self-efficacy index of Lithuanian students has fallen since 2016 to 2022, and students’ confidence in their own abilities has also decreased compared to the average of other countries. The international study (ibid) shows that in schools in Lithuania, compared to other countries, students have more opportunities to try democratic processes, however, the participation of students in civic activities has decreased. Moreover, the number of students who intend to actively participate in school activities related to citizenship in the future has decreased. Although the number of eighth-graders willing to volunteer and help the local community increased, the percentage of participating in youth-related political organizations decreased. It is this context that presupposed the aim of the research presented in this article – to analyze the social-educational factors of children’s citizenship education in basic school. The object of the research is social-educational factors of children’s citizenship education.

Research Methodology

Using the suggestions of Schugurensky & Myers (2008) for twenty-first century citizenship education, it was decided to analyze the citizenship of basic school students according to one dimension: from passive student to active student. This dimension predicts a movement from uncivil behavior towards citizenship, therefore, the factors identified by researchers (Davison, 2000; Chawla & Heft, 2002; Horwath et al., 2012; Lansdown et al., 2014; Lim, 2015; Reichert & Torney-Purta, 2018; Chia & Zhao, 2020; Wolhuter, et al., 2020; Sant et al., 2022) can be used to reveal the change:

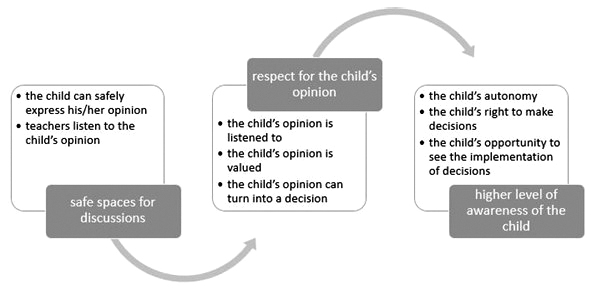

• Safe spaces for discussion where children can express their opinions are essential.

• Children’s opinions must be heard and taken seriously.

• Adults’ respect for the child’s opinion helps the child develop greater independence and a higher level of self-determination.

Figure 1

Theoretical model of the factors of citizenship education

The specified factors are quite elastically interrelated. Their paraphrasing is consistent with the strategy of experiential learning (Gerulaitienė, 2013; Povilaitytė & Lenkauskaitė, 2020; Šalkauskaitė, 2021): if children feel respected by adults, then they understand that they are listened to and their position is valued, and this allows them to confidently express their opinions. The identified factors are also consistent with the concept of citizenship defined by Olson et al. (2014): citizenship is understood as a relationship influenced by identity, social status, cultural preconditions, institutional practices, and a sense of belonging. Thus, respect for the child’s opinion and the child’s courage to express his/her opinion shape the cultural preconditions of the school as an institution, the operational practices and the students’ sense of belonging to the school community. Referring to the concept of citizenship and the defined factors of citizenship education, the theoretical model of citizenship education formed by the authors of the article is illustrated in Figure 1.

In the theoretical model of the factors of citizenship education, the previously mentioned highest level of the citizenship dimension by Schugurensky & Myers (2008) would be associated with the child’s higher level of awareness, active participation in school events, campaigns, and self-government, meanwhile, safe spaces for discussion, i.e., the opportunity for the child to freely express his/her opinion and be heard would be associated with the starting point of the factors of citizenship education. The theoretical model emphasizes the recognition of the child’s opinion and attitude. The emphasis of the model indirectly indicates another latent variable – teachers, school professionals, without whose positive attitude children’s opinions would not be heard and recognized. Hence, the relationship between children and school professionals (trust/distrust) could be another factor in citizenship education. Referring to the theoretical model of citizenship education, two hypotheses can be made:

Hypothesis No. 1: respect for the child’s opinion is positively related to the child’s involvement in the life of the school community, participation in self-government.

Hypothesis No. 2: respect for the child’s opinion is positively related to trust in school staff.

Research instrument. The survey used the Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education (Valuckienė, Balčiūnas, Būdvytytė, Cibulskienė, & Petukienė, 2017), which, with the consent of the authors, was adapted for basic school students, taking into account the aim of this research. The Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education consisted of 48 statements, which were grouped into several meaningful groups: trust in the school staff (10 statements, among which the classroom teacher, classroom tutor, educational support specialists, representatives of the school administration are named); interest in the surrounding environment (5 statements describing interest in the news of the classroom, the city, Lithuania and the world); participation in self-government (3 statements that reveal involvement in self-government elections and classroom life); ecology and social support (7 statements revealing the student’s activity and awareness in supporting the “green course,” providing social support to community members); commitment to values (5 statements describing commitment to the values of truth, honesty, justice, compassion); sense of belonging to a community (4 statements describing a sense of belonging to a community); courage to express one’s opinion and respect for the child (7 statements describing the student’s sense of the needs for self-esteem and respect being met); community celebrations and events (7 statements defining the student’s relationship with community events). A Likert scale was used to evaluate each statement reflecting the aspect of citizenship, where the respondents rated the answer options from 1 to 5 points (1 – yes; 2 rather yes; 3 – neither yes nor no; 4 – rather no; 5 – no).

The adapted structure of the statements of the Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education by Valuckienė et al. (2017) includes the factors of the theoretical model of citizenship: the group of statements the child’s opportunity to express his/her opinion and respect for the child directly reflects the safe discussion space and respect for the child’s opinion of the theoretical model; the groups of statements active participation in community life, ecology and social support reflect a higher level of awareness and participation in self-government in the theoretical mode; sense of belonging to the community, community events include identification with the community and responds to the concept of citizenship by Olson et al. (2014).

The structure of the questionnaire by Valuckienė et al. (2017) reveals a broader context of citizenship factors than was defined in the theoretical model of the factors of citizenship education. The groups of statements interest in the surrounding environment and commitment to values do not seem to have any relation to the model, however, in the adapted version of the Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education, these groups of statements are left due to information entropy. It is likely that the theoretical model does not reflect all the factors associated with citizenship education. Therefore, while confirming/refuting the proposed hypotheses, the validity and reliability of the Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education (Valuckienė et al., 2017) will be checked at the same time.

Research procedure. Schools cooperating with the research institution were invited to participate in the study. After obtaining the consent of the school administrations to organize the study, an electronic questionnaire form was sent to the classroom tutors with a request to familiarize the parents/guardians of the study participants (students) with the aim and procedures of the study and to obtain consent for the child’s participation in the study. The minors were also informed about their voluntary participation in the scientific research and the possibility to withdraw from it at any time. The survey was organized in compliance with the principles of research ethics that ensure the safety of research participants, i.e.: respondents participated in the study of their own free will, they were not subjected to external pressure, data were collected in accordance with the requirements of confidentiality and anonymity – the questionnaire did not include any questions allowing identification of the person’s identity, and did not ask to provide the student’s personal data.

Research methods. The collected data were processed by the SPSS 28 software. Descriptive mathematical statistics were used to define sample characteristics. Methods of multivariate statistical analysis: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis CFA) were used to determine the structural validity of the factors of citizenship education, correlational analysis was used to evaluate the convergent validity of the factors of citizenship education, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire.

Sample characteristics. 233 basic school students aged 11–14 participated in the online survey, of whom N = 138 (59.2%) were girls, N = 95 (40.8%) were boys. More than half (N = 146; 62.7%) of the children who participated in the survey live in medium-sized towns of Lithuania, slightly more than a quarter (N = 62; 26.6%) live in large cities, the smaller number of respondents (N = 19; 8.2%) were from small towns, only a few (N = 4; 1.7%) respondents were from small settlements; two children (0.9%) did not specify their place of residence.

Analysis of the research results

In the first phase of the study, EFA was performed (Principal component method with Varimax rotation), in search of the most favorable factor structure, removing statements with an anti-Image correlation coefficient MSA < 0.7, weight < 0.4, and the coefficient of commonality of factors < 0.2. EFA was performed 4 times. It was obtained that Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.886; Approx. Chi-Square = 2849.717; df = 231; p = 0.000. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient reveals that the data fit well in EFA. The Varimax rotation extracted five factors: child’s trust in the school staff (CTSS); child’s relationship with community events (CRCE); adults’ respect for the child’s opinion (ARCO); child’s interest in news (CIN), child’s participation in school self-government (CPSS). The obtained factor structure preserves 66.714% of the information provided by the subjects. The compatibility coefficient of the obtained factor structure Cronbach Alpha = 0.922 is very high. This means that the obtained Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education can be used not only for group but also for individual diagnostics when Cronbach Alpha > 0.8 (Vaitkevičius & Saudargienė, 2010, p. 102).

The obtained factor structure only partially corresponds to the factors of citizenship education defined by Davison (2000), Chawla & Heft (2002), Horwath et al. (2012), Lansdown et al. (2014), Lim (2015), Reichert & Torney-Purta (2018), Chia & Zhao (2020), Wolhuter et al. (2020), Sant et al. (2022): adults’ respect for the child’s opinion is a middle factor intervening between the factors child’s trust in the school staff, relationship with community events, child’s interest in news and child’s participation in school self-government. In the extracted factor structure, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion does not have a dominant place emphasized by Davison (2000), Chawla & Heft (2002), Horwath et al. (2012), Lansdown et al. (2014), Lim (2015), Reichert & Torney-Purta (2018), Chia & Zhao (2020), Wolhuter et al. (2020), Sant et al. (2022). Child’s interest in news is the factor that was not singled out as a citizenship education factor in the works of the aforementioned authors.

The factor of child’s participation in school self-government, according to the concept of citizenship defined by Olson et al. (2014), reveals the consequence of the factors suitable for citizenship education – the student’s activity in the life of the community. The variables in this factor were permuted and transformed. The decision to permute and transform the factor variables was made because those variables that were weighted by Varimax rotation had to be removed from the structure of the citizenship model obtained by the CFA. Therefore, the EFA was redone. New variables were formed from two variables that were similar in meaning (Pakalniškienė, 2012):

1) The variable to elect a class elder and the variable trust in the class elder form a new variable: “Trust in the class elder and participation in the elections of the elder”;

2) The variable trust in the classmates and the variable you can openly express your opinion in the classroom, even if it does not agree with the opinion of another student form a new variable “Trust in the classmates and the courage to express one’s opinion”;

3) The variable trust in the classroom tutor/teacher and the variable the students in our class may disagree with the opinion of the teacher/tutor form a new variable: “Trust in the teacher, classroom tutor and expressing one’s opinion”

Table 1 presents the participation in self-government factor formed from the combined variables.

Table 1

Results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

|

Statements of the Citizenship Scale |

Factors with variances |

Cronbach Alpha |

||||

|

CTSS |

CRCE |

ARCO |

CIN |

CPSS |

||

|

1. Trust in the deputy principal |

.867 |

|

|

|

|

0.924 |

|

2. Trust in the speech therapist |

.850 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Trust in the special educator |

.847 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Trust in the school principal |

.844 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Trust in the librarian |

.804 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Trust in the social educator |

.709 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Trust in the teacher’s assistant |

.636 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. School events for Lithuanian national holidays |

|

.775 |

|

|

|

0.876 |

|

9. Socially beneficial activities |

|

.752 |

|

|

|

|

|

10. News about your school’s activities (events, campaigns, joint excursions) |

|

.713 |

|

|

|

|

|

11. Trips, excursions |

|

.694 |

|

|

|

|

|

12. School events for Christmas and Easter |

|

.679 |

|

|

|

|

|

13. Meetings with famous people |

|

.672 |

|

|

|

|

|

14. Other family members (grandparents, siblings) listen to and respect my opinion |

|

|

.874 |

|

|

0.802 |

|

15. Parents listen to and respect my opinion |

|

|

.820 |

|

|

|

|

16. Teachers listen to and respect my opinion |

|

|

.656 |

|

|

|

|

17. World news (war in Ukraine, fuel price, Russian politics, etc.) |

|

|

|

.843 |

|

0.580 |

|

18. News about events and problems in your city |

|

|

|

.689 |

|

|

|

19. News from Lithuania (politics, sports, events in Lithuania) |

|

|

|

.676 |

|

|

|

20. Trust in the teacher, classroom tutor and expressing one’s opinion |

|

|

|

|

.769 |

0.618 |

|

21. Trust in the classmates and the courage to express one’s opinion |

|

|

|

|

.512 |

|

|

22. Trust in the class elder and participation in the elections of the elder |

|

|

|

|

.480 |

|

|

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. |

||||||

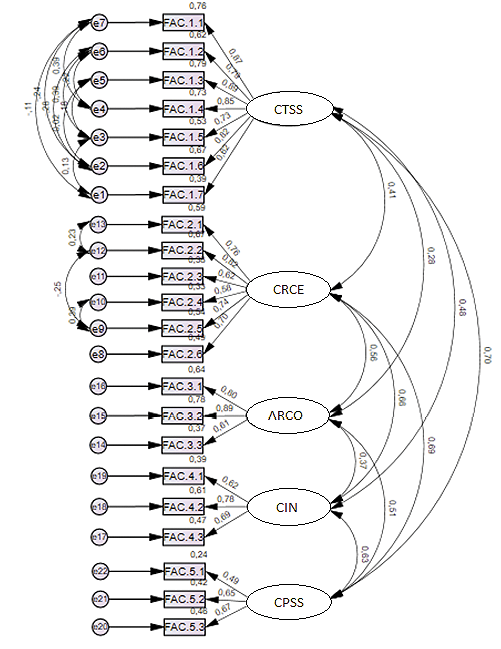

The citizenship education model obtained in the second phase of the study (Fig. 2) was tested by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The goodness-of-fit criteria for the model of factors of citizenship education derived from the CFA: Chi-square = 292.598; df = 190; p-value = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.046; CFI = 0.967; TLI = 0.959; IFI = 0.967; sRMR = 0.0514. The confirmatory factor analysis model meets the criteria of a good model RMSEA1<0.08; sRMR2<0.08; CFI3>0.95; TLI4>0.95; IFI>0.95.

The model of citizenship education shows a strong correlation r = 0.7 (p < 0.001) between the factors child’s trust in the school staff and participation in school self-government, between the factors child’s relationship with community events and participation in school self-government r = 0.69 (p < 0.001); between the factors child’s relationship with community events and child’s interest in news r = 0.66 (p < 0.001), between the factors child’s interest in news and participation in school self-government r = 0.63 (p < 0.001); an average correlation between the factors child’s relationship with community events and teachers’ respect for the child’s opinion r = 0.56 (p < 0.001). Strong correlations between child’s trust in the school staff and participation in school self-government, between child’s relationship with community events and participation in school self-government reveal a slightly different relationship between the factors of citizenship education than was discovered after analyzing the statements of Davison (2000), Chawla & Heft (2002), Horwath et al. (2012), Lansdown et al. (2014), Lim (2015), Reichert & Torney-Purta (2018), Chia & Zhao (2020), Wolhuter et al. (2020), Sant et al. (2022). The confirmatory factor analysis clarified the Lithuanian context of the structure of the factors of citizenship education. The main factor is not adults’ respect for the child’s opinion but child’s trust in the school staff. The main factor child’s trust in the school staff has a direct strong connection (r = 0.7; p < 0.001) with the factor of child’s participation in school self-government.

Figure 2

5-factor citizenship education model

Note: CTSS – child’s trust in the school staff; CRCE – child’s relationship with community events; ARCO – adults’ respect for the child’s opinion; CIN – child’s interest in news; CPSS – child’s participation in school self-government.

Correlations of moderate strength were found between the factors child’s trust in the school staff and child’s relationship with community events r = 0.41 (p < 0.01) and between the factors child’s trust in the school staff and child’s interest in news r = 0.48 (p < 0.01).

The weakest correlations are between the factors child’s trust in the school staff and teachers’ respect for the child’s opinion r = 0.27 (p < 0.01) and between the factors teachers’ respect for the child’s opinion and child’s interest in news r = 0.37 (p < 0.01).

The CFA revealed positive correlations between the factors and confirms the hypotheses. A positive correlation of moderate strength was established between the factors teachers’ respect for the child’s opinion and child’s relationship with community events r = 0.56 (p < 0.001). A positive correlation of moderate strength was also established between the factors teachers’ respect for the child’s opinion and child’s participation in school self-government r = 0.51 (p < 0.001). Both the factor child’s participation in school self-government and the factor child’s relationship with community events reveal the child’s involvement in the life of the school community. Therefore, it can be said that the first hypothesis – respect for the child’s opinion is positively related to the child’s involvement in the life of the school community – is confirmed.

The CFA revealed a positive but weak correlation between the factors adults’ respect for the child’s opinion and child’s trust in the school staff r = 0.28 (p < 0.01). Thus, the second hypothesis – respect for the child’s opinion is positively related to trust in school staff – is also confirmed.

The research results refine the structure of the Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education by Valuckienė et al. (2017): out of 48 statements, 22 remained, making up 5 factors that define the factors of citizenship education in Lithuanian basic school: the dominant factor covering 22.4% of the variance of the data is child’s trust in the school staff. This factor reveals that in order to strengthen citizenship education, it is important to build and develop students’ trust in the school staff. It can be said that students’ trust in the school staff means that children’s needs, interests, opinions are represented. It is important to emphasize that trust in the school staff does not mean absolute trust. Figure 2 shows a dense network of both positive and negative covariances in the structure of the factor child’s trust in the school staff. Positive and negative coefficients reveal that some specialists are trusted more, while others, on the contrary, are not trusted. In developing citizenship, it is important to increase cohesion among school staff, because adults are role models for children. The factor child’s trust in the school staff has a direct relationship with the factor child’s participation in school self-government.

The second factor – child’s relationship with community events – covers 16.9% of the data variance. This factor also has a direct relationship with the factor child’s participation in school self-government. It means that if we expect active involvement and participation of students, it is important to celebrate traditional holidays together, organize excursions, trips, meetings with famous people, engage in socially beneficial activities with students. The third factor – adults’ respect for the child’s opinion – does not occupy the main place, which could have been predicted. This factor explains only 10.4% of the variance in the data, however, it has direct reciprocal relationships with the factors child’s relationship with community events and child’s participation in school self-government. This means that only when community events take place and school self-government develops, respect for the child’s opinion can occur and vice versa.

Child’s interest in news is a factor that has not been singled out in the sources of literature, however, it has a direct relationship with the factor child’s relationship with community events and the factor child’s trust in the school staff. Child’s interest in news explains 9% of the variance in the data. Relatively strong correlations of this factor with other factors indicate that it is an important factor in citizenship education, which connects external educational factors with the student’s personal motives.

Summing up the empirical results of the structure of the factors of citizenship education, it can be said that they refine the theoretical model: the factor adults’ respect for the child’s opinion is not the main factor in citizenship education. In the context of Lithuanian basic schools, the dominant factor in the structure of the factors of citizenship education is child’s trust in the school staff. No less important factors for the development of citizenship are child’s relationship with community events, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, child’s interest in news, child’s participation in school self-government.

The analysis of empirical data refined the structure of the Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education by Valuckienė et al. (2017). According to the obtained data, it can be stated that the revised Citizenship Education Model is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring the factors of students’ citizenship education.

Discussion

The successful participation of children in school life and government basically depends on purposeful and systematic educational work in the educational institution and in the family, getting to know the children better and motivating them, encouraging them, establishing/creating an environment for their personality to unfold. The research carried out by the authors of the article not only extends but also complements the research Developing Civic Leadership in Schools: Experiences of Success carried out by the researchers Valuckienė et al. (2017). When evaluating the results of the study in the context of ICCS (2023), the identified factors of citizenship education have links with the results and recommendations of the international study. It is becoming evident that the features of citizenship of students emphasized in ICCS (2023) – student-teacher relationships, openness to discussion and microclimate of the classroom, participation of students in school activities, students’ confidence to act independently, interest in social and political life – are semantically close and very similar to all the factors of citizenship education identified during this study: child’s trust in the school staff, child’s relationship with community events, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, child’s participation in self-government, child’s interest in news.

On the other hand, during the ICCS (2023) study, it was found that the citizenship index of Lithuanian students in attributes that are related to such factors as child’s trust in the school staff, child’s relationship with community events, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, child’s participation in self-government has been declining since 2016.

This fact is not an encouraging result because the participation of students in school life and government is one of the important parts of citizenship education. As explained in the comparative analysis of the concept of citizenship (Pilietiškumas ir pilietinė visuomenė [Citizenship and Civil Society], 2012), it is necessary to understand citizenship as an idea of responsibility. Only a person who has the right to decide, who sets goals for himself/herself and seeks ways to realize them, is responsible for the consequences of such a choice. A citizen who has the right to make mistakes may choose inappropriate social goals and inappropriate patterns of behavior, however, only such a citizen can act according to the principle of shared responsibility. A citizen’s sense of personal responsibility and opportunities to act give the citizen a chance for uniqueness, exclusivity, and true individuality.

The results of the conducted research reveal that the relationship between the dominant factor (child’s trust in the school staff) and other factors has a tendency of amplification. Trust in the scientific discourse is seen as a construct that encompasses the contexts of different social relationships: from interpersonal trust among members of the school community to the elements of the formation of social capital (Stonkė, 2023). The circulation of trust in the state fosters the general need of society to trust the state and the structures representing it, to be guided by an optimistic view of the future and the belief that both civil society and the state government structure are guided by the same values and behavioral norms in implementing the common goals of the state’s development.

Some studies show that some students do not perceive school as a place where joint decisions are made or where there are opportunities for participation (Forde et al., 2018). The students do not feel heard (Keisu &Ahlström, 2020) – even in class and school councils – and they barely have a chance to really make an impact (Andersson, 2019). However, a study conducted by Swiss researchers Müller-Kuhn et al. (2021) confirmed that most students perceive school to some extent as a place where they can participate, have a voice, and are actively involved. Children’s basic skills and competences are necessary for successful participation (Sadownik, 2018), and motivation to go to school supports participation (Aziz et al., 2018). If schools want to continue to develop towards greater participation, they need time for this process – to pay attention to school culture, to include participation and to see the value of participation (Müller-Kuhn et al., 2021).

When evaluating the results of the conducted research, it is important to realize that students’ activity in participating in school and/or classroom life depends on many factors, for example, the conditions created in the school for students to participate in decision-making, encouraging students to propose ideas for changes in school life, organizing participative class meetings, voting, etc. However, the pedagogical approach of the teachers themselves towards students’ citizenship education is also very important, i.e., on what philosophical basis the education of citizenship is based in the classroom, on what vision and aim citizenship education is based in the school. It is obvious that the absence of a clear goal also hinders the teacher’s own pedagogical decisions that would encourage students to be active, creative, and critical. It is important to emphasize that the teacher’s pedagogical decisions should be focused on very specific actions – encouraging students to be interested in the news, discuss it, respect the child’s opinion (and this is significant not only in the student–teacher relationship, but also in the relationship between the student and other members of the school community). It means that Lithuanian schools still need to strengthen what was observed in other countries a few years or even decades ago: schools must provide safe spaces for discussion where children can express their opinions and work with adults to solve current problems of society (Lim, 2015; Reichert & Torney-Purta, 2018); children must be given the opportunity to express their views, present arguments and negotiate, and this must be heard and taken seriously (Chawla & Heft, 2002; Lansdown et al., 2014), because this is the only way to create conditions for children to solve various questions and problems constructively (Horwath, Kalyva, & Spyru, 2012), develop greater independence and a higher level of self-determination (Kosher, Jiang, Ben-Arieh, & Scott, 2014).

The study has some limitations. Since the quantitative study was carried out, it would make sense to conduct a qualitative study with the students as well, so that we could analyze the expression of citizenship education through the child’s experience in more detail. It would be possible to widen the sample of subjects in terms of the geography of the study by location and type of educational institution. It would be possible to conduct a study not only with students studying in cities and towns, but also with students studying in rural areas. The subjects could be not only basic school students, but also gymnasium students, etc. We are also planning to conduct a quantitative and qualitative study with teachers and parents in the future. Further perspectives of the study are planned in order to obtain more reliable and detailed research data, the results of which would represent all regions of Lithuania.

Conclusions

The analysis of scientific sources, national and international education documents confirms the relevance and importance of children’s citizenship education and allows us to say that citizenship education is one of the most relevant issues of the state and education policy in recent years, not only in Lithuania, but also in many foreign countries.

A citizenship education model based on empirical data:

• confirmed the hypothesis: there is a moderately strong correlation between respect for the child’s opinion and the child’s involvement in the life of the school community (r = 0.56; p < 0.001), and there is a moderately strong correlation between respect for the child’s opinion and the child’s participation in school self-government (r = 0.51; p < 0.001);

• confirmed the hypothesis: there is a weak positive correlation between respect for the child’s opinion and trust in the school staff (r = 0.28; p < 0.05);

• refines the theoretical model of citizenship education: the dominant factor is not adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, but child’s trust in the school staff;

• refined the structure of the Questionnaire for the Situation of Citizenship Education by Valuckienė et al. (2017): according to the data obtained, it can be stated that the revised Citizenship Education Model is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring the factors of students’ citizenship education.

The study made it possible to distinguish the social-educational factors important for citizenship education: child’s trust in the school staff, child’s relationship with community events, adults’ respect for the child’s opinion, child’s interest in news and child’s participation in self-government.

References

Aziz, F., Quraishi, U., & Kazi, S. A. (2018). Factors behind classroom participation of secondary school students (A gender based analysis). Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(2), 211–217. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060201

Andersson, E. (2019). The school as a public space for democratic experiences: formal student participation and its political characteristics. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 14(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197918776657

Chawla, L., & Heft, H. (2002). Children’s competence and the ecology of communities: A functional approach to the evaluation of participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2002.0244

Chia, Y. T., & Zhao, Z. (2020) Citizenship and Education in China: Contexts, Perspectives, and Understandings. Chinese Education & Society, 53(1–2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2020.1716590

Cleovoulou, Y. (2021). 21st Century Pedagogies and Citizenship Education: Enacting Elementary School Curriculum Using Critical Inquiry-Based Learning. In M. J. Hernández-Serrano (Eds.), Teacher Education in the 21st Century – Emerging Skills for a Changing World. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96998

Duarte, J. (2021). “Global citizenship means different things to different people”: Visions and implementation of global citizenship education in Dutch secondary education. Prospects, 53(1), 407-424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-021-09595-1

European Commission, European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Sigalas, E., De Coster, I. (2018). Citizenship education at school in Europe, 2017, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/778483

Forde, C., Horgan, D., Martin, S., & Parkes, A. (2018). Learning from children’s voice in schools: experiences from Ireland. Journal of Educational Change, 19(4), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833- 018-9331-6

Galea, S. (2020). Compassion in a time of COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10241), 1897–1898. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31202-2

Gerulaitienė, E. (2013). Patirtinio mokymosi kitame kultūriniame kontekste ugdymo praktikos, plėtojant tarpkultūrinę kompetenciją, ypatumų analizė [Analysis of peculiarities of experiential learning in different cultural context: development of intercultural competence]. Jaunųjų mokslininkų darbai [Journal of Young Scientists], 1(39), 25–31. https://epublications.vu.lt/object/elaba:6097569/6097569.pdf

Gürkan, B., & Doğanay, A. (2020). Factors affecting citizenship education according to perceptions and experiences of secondary-school teachers. Turkish Journal of Education, 9(2), 106–133. https://doi.org/10.19128/turje.592720

Horwath, J., Kalyva, E., & Spyru, S. (2012). “I want my experiences to make a difference” promoting participation in policy-making and service development by young people who have experienced violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.09.012

James, A., & Davison, J. (2000). Social literacy and citizenship education in the school curriculum. Curriculum Journal, 11(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851700361366

Keisu, B. I., & Ahlström, B. (2020). The silent voices: pupil participation for gender equality and diversity. Educational Research, 62(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1711436

Kosher, H., Jiang, X., Ben-Arieh, A., & Scott, E. (2014). Advances in children’s rights and children’s well-being measurement: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000051

Lansdown, G., Jimerson, S. R., & Shahroozi, R. (2014). Children’s rights and school psychology: Children’s right to participation. Journal of School Psychology, 52(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.006

Lietuvos pažangos strategija „Lietuva 2030“ [Lithuania’s Progress Strategy “Lithuania 2030”]. (15 May 2012 ). Valstybės žinios [State News]. http://lms.lt/archyvas/files/active/0/2011-02-18_Lietuva2030.pdf

Lim, L. (2015). Critical thinking, social education and the curriculum: foregrounding a social and relational epistemology. Curriculum Journal, 26(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.975733

Moorse, L. (2019). Citizenship Education in England: Policy and Curriculum. In A. Peterson, G. Stahl, & H. Soong (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67905-1_22-1.

Müller-Kuhn, D., Herzig, P., Häbig, J., & Zala-Mezö, E. (2021). Student participation in everyday school life – Linking different perspectives. Z f Bildungsforsch 11, 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-021-00296-5

Olson, M., Fejes, A., Dahlstedt, M., & Nicoll, K. (2015) Citizenship discourses: production and curriculum. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 36(7), 1036–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.883917

Pagrindinio ugdymo mokinių socialinės-pilietinės ir pažintinės kultūrinės veiklos organizavimas bendrojo ugdymo mokyklose: Tyrimo ataskaita [Organization of basic education students’ socio-civic and cognitive cultural activities in general education schools: Research report]. (2020). Vilnius: Nacionalinė švietimo agentūra [National Agency for Education]. https://www.nsa.smm.lt/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Socialine_pilietine_kulturine_pazintine_veikla.pdf

Pakalniškienė, V. (2012). Tyrimo ir įvertinimo priemonių patikimumo ir validumo nustatymas [Determining the reliability and validity of research and assessment tools]. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla [Vilnius University Press].

Pilietiškumas ir pilietinė visuomenė: Lyginamoji pilietiškumo sampratos analizė [Citizenship and civil society: A comparative analysis of the concept of citizenship]. (2012). Vilnius: Nevyriausybinių organizacijų informacijos ir paramos centras [Information and support centre for non-governmental organizations]. http://www.3sektorius.lt/docs/Pilietiskumas_analize_final_2013-01-17_16_00_54.pdf

Povilaitytė, J., & Lenkauskaitė, J. (2020). Mokinio autentiškos patirties įprasminimo būdai pradinio ugdymo procese [Ways to making the student’s authentic experience meaningful in the process of primary education]. Jaunųjų mokslininkų darbai [Journal of Young Scientists], 50(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.21277/jmd.v50i1.286

Reichert, F., & Torney-Purta, J. (2018). A cross-national comparison of teachers’ beliefs about the aims of civic education in 12 countries: A person-centered analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.005

Sadownik, A. (2018). Belonging and participation at stake. Polish migrant children about (mis)recognition of their needs in Norwegian ECECs. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(6), 956–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533711

Sant, E., González-Valencia, G., Shaikh, G., Santisteban, A., Costa, M., Hanley, Ch., & Davies, I. (2022). Characterising citizenship education in terms of its emancipatory potential: reflections from Catalonia, Colombia, England, and Pakistan, Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2022.2110840

Saperstein, E. (2023). Post-pandemic citizenship: The next phase of global citizenship education. Prospects, 53, 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-021-09594-2

Schugurensky, D., & Myers, J. P. (2008). Citizenship Education: Theory, Research and Practice. Encounters on Education, 4, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.24908/eoe-ese-rse.v4i0.655

Slavich, G. M., Roos, L. G., & Zaki, J. (2022). Social belonging, compassion, and kindness: Key ingredients for fostering resilience, recovery, and growth from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 35(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1950695

Stonkė, E. (2023). Pasitikėjimu grįstas viešasis valdymas: Skandinavijos regiono modelio dekonstrukcija [Trust-Based Governance: deconstructing: the Scandinavian regional model]. Regional Formation and Development Studies, 2(40), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.15181/rfds.v40i2.2538

Šalkauskaitė, P. (2021). Patirtinio ugdymo patirtys ir atradimai pradinėje mokykloje [Experiential education experiences and discoveries in a primary school]. Švietimas: politika, vadyba, kokybė [Education Policy, Management and Quality], 13(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.48127/spvk-epmq/21.13.98

Tarptautinis pilietinio ugdymo ir pilietiškumo tyrimas ICCS 2022: Rezultatų pristatymas [ICCS 2022 International Survey of Civic Education and Citizenship: Presentation of Results]. (2023). https://www.nsa.smm.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/ICCS-2022-Pristatymas_2023-11-28_compressed.pdf

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021, April 14). What are the core characteristics of Generation Z? https://www.aecf.org/ blog/what-are-the-core-characteristics-of-generation-z

Vaitkevičius, R., & Saudargienė, A. (2010). Psichologinių tyrimų duomenų analizė [Analysis of psychological research data]. Kaunas: VDU leidykla.

Valstybės pažangos strategija „Lietuvos ateities vizija „Lietuva 2050“ [State Progress Strategy “Lithuania’s Future Vision “Lithuania 2050”]. Retrieved from: https://atvirasseimas.lrs.lt/processes/iniciatyvos-vizija-LT2050?locale=lt

Valuckienė, J., Balčiūnas, S., Būdvytytė, A., Cibulskienė, D., & Petukienė, E. (2017). Pilietinės lyderystės ugdymas mokyklose: sėkmės patirtys [Developing civic leadership in schools: experiences of success]. Prienų švietimo centras: UAB Vitae Litera.

Wolhuter, Ch., Janmaat, J. G., van der Walt, J. (Hannes) L, & Potgieter, F. J. (2020). The role of the school in inculcating citizenship values in South Africa: Theoretical and international comparative perspectives. South African Journal of Education, 40(Suppl. 2), s1–s11. http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40ns2a1782

Zaleskienė, I. (2014). Pilietiškumo ugdymo(si) didaktikos raida švietimo reformos kontekste [Development of citizenship education didactics in the context of education reform]. In R. Bruzgelevičienė (Ed.), Ugdymo paradigmų iššūkiai didaktikai: Kolektyvinė monografija [Educational paradigm challenges for didactics: Collective monograph] (pp. 284–308). Vilnius: Lietuvos edukologijos universiteto leidykla [Publishing House of the Lithuanian University of Education]. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12259/97752

1 RMSEA – Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). This error in the confirmatory factor analysis model should be less than 0.08.

2 sRMR – Standardized root mean square residual.

3 CFI – Comparative-fit index (CFI). Greater than 0.90, it indicates an adequate fit between the model and the data, and greater than 0.95, it indicates a good fit between the model and the data (Pakalniškienė, 2012, p. 68).

4 TLI – Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), “similar to CFI, it compares the model under test to the null model” (Pakalniškienė, 2012, p. 68).