Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2023, vol. 13, pp. 76–97 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2023.13.15

The Role of Organisational Climate in Employee Well-Being and the Occurrence of Workplace Violence: Contextualisation of Theoretical Constructs

Tomas Butvilas

Kazimieras Simonavičius University / School of Business Innovations, Lithuania

tomas.butvilas@ksu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4890-559X

Andrius Janiukštis

Kazimieras Simonavičius University / School of Business Innovations, Lithuania

Remigijus Bubnys

Kaunas University of Technology / Panevėžys Faculty of Technology and Business, Lithuania

remigijus.bubnys@ktu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7614-7688

Rita Lūžienė

Vilnius Simonas Daukantas Progymnasium, Lithuania

Annotation. Research has shown the importance of microclimates for employee behaviour, organisational performance and individual employee well-being; also, the negative implications of workplace violence for organisational microclimate and employee well-being. This paper aims to shed light on the theoretical aspects of organisational microclimate, employee well-being and workplace violence, and to offer theoretical insights into the role of microclimate in employee well-being and the occurrence of workplace violence. To achieve this objective, an analysis and synthesis of recent scientific publications was chosen. The results revealed the theoretical links between the organisational microclimate and the emergence of workplace violence, as well as the negative implications of workplace violence for employee well-being and the further spread of violence in the organisation. This study will contribute to further empirical research on the role of organisational microclimate in employee well-being and the emergence of workplace violence.

Keywords: organisational climate, employee well-being, violence at workplace, discourse.

Received: 2023-09-06. Accepted: 2023-12-12

Copyright © 2023 Tomas Butvilas, Andrius Janiukštis, Remigijus Bubnys, Rita Lūžienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The complexity of how an organisation operates is increasing due to rapid changes in the business environment. Globalisation, depleting resources, high technology, financial scandals, bankruptcies, catastrophes and external pressures from various societal groups are increasingly forcing companies to take into account the growing complexity of business operations in order to achieve resilience, longevity and sustainability. It is important for business success to take into account not only the external factors affecting business, but also the internal factors.

Researchers focus on the microclimate of an organisation because it is a phenomenon that has a significant impact on the behaviour and performance of an organisation’s employees, as well as on the organisation’s own performance. It is also related to employees’ attitudes, values and perceptions of the organisation as a set of individual characteristics of the organisation. The importance of a positive organisational climate is that it increases employees’ job satisfaction, positively influences how employees feel about their work environment, their performance and their interactions with each other (Rimbayana, Erari and Aisyah, 2022), (Afe et al. 2019), (Osmani et al. 2022). Another equally important phenomenon related to employees and their surrounding work environment is employee well-being. This is usually defined as a positive physical, emotional and psychological state of employees, which is satisfying and results from a supportive working atmosphere in which the employee is able to realise his or her personal and professional potential. Positive employee well-being is most often associated with higher job performance, job satisfaction, productivity and task efficiency, lower absenteeism and other factors (Ponting, 2020), (Salleh et al. 2020), (Kahtani and Sulphey 2022). On the other hand, there are phenomena in organisations that have a negative impact on the well-being or health of employees, such as workplace violence, which refers to deliberate behaviour by those inside or outside the organisation that is intended to cause physical, psychological or emotional harm to employees. Workplace violence is associated with negative effects on employee well-being, such as negative financial consequences, psychological or emotional problems, burnout syndrome, reduced productivity or job satisfaction (Gembalska-Kwiecień 2020), (Vévodová, Vévoda, and Grygová 2020), (Pacheco et al. 2021). However, a theoretical analysis of the literature reveals that research work has focused on exploring the role of microclimate on individual factors related to employee well-being, as well as the role of violence in the work environment on employees’ health and well-being. At the same time, there is a lack of clear-cut answers and a lack of instruments to understand the role of the organisational microclimate in employee well-being and the occurrence of workplace violence. Investigating the relationship between organisational microclimate, employee well-being and workplace violence will contribute to a better understanding of this relationship and encourage further empirical research. Therefore, this paper formulates the following research question: what are the implications of organisational climate for employee well-being and the occurrence of violence in the work environment? The object is the theoretical aspects of the role of organisational climate in employee well-being and the occurrence of violence in the work environment.

The aim of this paper is to examine the theoretical aspects of the role of organisational climate in employee well-being and the occurrence of workplace violence. To achieve this aim, the objectives are: to highlight the theoretical aspects of organisational microclimate, employee well-being and workplace violence; to provide theoretical insights into the role of organisational microclimate in employee well-being and the occurrence of workplace violence.

Methods: comparative analysis, synthesis and generalisation of scientific literature. The literature search for this work was carried out in February 2023. SCOPUS, JSTOR, ERIC, EBSCO electronic databases were used to conduct the search based on titles, keywords and abstracts of publications. The following keywords were used in the search: microclimate – microclimate, organisational microclimate, organisational climate, security climate, working conditions, working atmosphere, positive working climate, work climate; violence in the work environment - violence, violence at work, violence in the work environment, psychological violence, mobbing, mobbing in the work environment, bullying, physical violence, sexual violence, emotional violence, psych-terrorism); employees’ welfare – employee welfare; labor welfare; well-being at work; well-being in the organization; work-life balance; welfare; quality of professional life. The scope included all publications that fulfilled the following criteria: original scientific articles and reports; publications written in English; publications related to the main themes of the work (organisational climate, employee well-being, violence in the work environment); publications published since 2018. A total of 172 scientific publications were selected through title selection, and a further 104 publications were removed after abstract review, bringing the total number of publications included in the review to 68.

The microclimate of the organisation: conceptualisation and expression

The concept of organisational microclimate was first mentioned in 1939 in the context of the Group Atmospheric Survey, and since then the phenomenon has been studied in an effort to measure the functioning and development of microclimates. An organisation’s microclimate can be defined as the overall totality of the organisation’s policies, practices and procedures as experienced by employees, as well as the expectation for certain behaviours that are seen, supported and encouraged (D’Amato, 2023; Kessler 2019). Given the differences between organisations, it can be argued that each organisation has a specific microclimate that reflects the governance of that organisation. As a result, scholars do not agree on the factors that make up the microclimate. Nevertheless, the literature analyses the links between microclimate and organisational culture (Osmani, Sejdiu and Yusufi 2022,) and individual employee perceptions of organisational culture, which are determined by the organisation’s beliefs, values and inherent behaviours (Dang, Tran and Tran, 2021). Two distinct perspectives emerge when analysing attempts to define the concept of organisational microclimate. The first perspective highlights the factors that characterise an organisation, the most commonly cited of which are the organisation’s policies, practices and procedures. The second one refers to individual perceptions, which are determined by human factors such as personal values, psychological desires or others (Diab, Diab and Emam 2021). From the first perspective, it can be said that an organisation’s climate is a set of characteristics that objectively characterise the organisation itself and allow it to be perceived by both internal employees and individuals outside the organisation (Rimbayana, Erari and Aisyah 2022). The second perspective is examined as an individual’s assessment of the work-related environment in terms of employees’ attitudes, feelings, norms and values. It is the perception of the organisation that employees share while working in the same work environment, which relates to the social environment that determines employee behaviour (Ozsoy, 2022; Luthufi et al. 2020; Afe et al. 2019). In addition to the usual attempts to study the concept of microclimate, a new trend has developed in the scientific literature that expands the concept of microclimate by introducing specific categories of this phenomenon. For example, supportive climate, which encompasses employees’ general perception of the supportiveness prevailing in the organisation, which helps to shape employees’ attitudes towards the organisation and influences their loyalty to the organisation (Li, Liang and Liu 2022). Safety climate, which is defined as the perceived collective safety behaviour that helps employees to understand safety priorities in the organisation and is associated with safety indicators such as injury rates or accidents (Jackson, Harper and McLean 2021). An inclusive microclimate, which is based on the perception of the balance between formal and informal organisational policies and the uniqueness of the organisation (Roberge et al. 2021) A national climate, which is characterised by a shared perception that employees are welcomed and valued equally in the organisation, regardless of the person’s background and nationality (Köllen, Koch and Hack 2020). A theoretical analysis of scholars’ work on the concept of microclimate suggests that an organisation’s microclimate is a set of individual characteristics that help it to stand out from other organisations, both from an internal and external perspective, and that have a significant impact on the behaviour, performance and results of its employees. It is the perception of the people who work in the organisation, linked to their attitudes and values, which manifests itself in their thoughts, feelings, behaviours and social relationships. It is a phenomenon that is influenced by the managers and members who make decisions in the organisation.

Figure 1

Organisational microclimate definition

Source: compiled by author

Looking at the interaction between an organisation and its employees, most research on organisational climate focuses on the work environment factors that not only characterise the organisation itself, but also have the greatest impact on its employees. These factors determine how employees perceive the organisation, and these perceptions are shared on a day-to-day basis in the formation of social relationships, thus creating implications for employee job satisfaction and performance (Vos and Page 2020,). The authors relate the dimensions of microclimate to employees’ perceptions, social interactions and influence on employees. Employee perception becomes an important subjective evaluation viewed through feelings of autonomy, trust, support for each other, employee appreciation, sense of justice, trust, support, recognition and innovation (Diab, Diab and Emam 2021; Osmani, Sejdiu and Yusufi, 2022). Another approach identifies more dimensions related to organisational characteristics by dividing them into five domains: Organisational trust (managerial support and evaluation, which are created by a trusting environment); job strain (stress at work, which negatively affects employees’ productivity, commitment, negative feelings at work, or evaluation of the job itself); social support (belonging to a social community and building relationships with others, creating a sense of trust and community); rewards (employees’ perception of whether there are opportunities for career advancement, more senior roles and higher rewards within the organisation); job satisfaction (evaluation of the work done, which gives a sense of job satisfaction) (Barría-González et al. 2021; Tadesse, 2019; Michalak, 2019) divide the dimensions of microclimate into six dimensions: Organisational clarity (clearly perceived expectations and their links to organisational performance); reward system (recognition and reward for work well done); organisational standards (perception that managers are important for employee engagement and performance); flexibility (belief that adequate constraints exist within the organisation); responsibility (feeling that the tasks delegated to employees are adequate); team involvement (satisfaction and pride in belonging to the organisation).

Researchers have also linked the dimensions of organisational microclimate to areas such as human relations, internal processes, open systems and rational goals (Diab, Diab and Emam 2021; Mueller and Surachaikulwattana 2020). To summarise the authors’ insights into these four dimensions, seventeen scales can be identified (see Table 1):

Table 1

Four dimensions of organisational microclimate

|

Microclimate dimensions |

Scales |

|

Human relations |

Autonomy (workplace design that enhances the ability to get things done); integration (cooperation and trust between departments); engagement (adequate influence on decisions); management support (perceived support of the organisation’s managers); training (perceived concern for the organisation’s staff’s development of knowledge and skills); welfare (perceived perception of the extent to which the organisation values and cares for its staff). |

|

Internal processes |

Formalisation (the extent to which the organization cares about formal rules and procedures); tradition (the extent to which customary practices and procedures are valued). |

|

Open systems |

Innovation and flexibility (orientation to change and fostering new ideas and motives); market orientation (the extent to which the organisation adapts to the needs of customers and the market); reflexivity (the extent to which the organisation is concerned with reviewing its strategy, work processes, objectives). |

|

Rational targets |

Clarity of the organisation’s objectives (the extent to which the organisation clearly defines its objectives); effectiveness (the perceived focus on staff effectiveness and productivity); effort (the perceived effort of the organisation’s staff in achieving its objectives); feedback (the extent to which the organisation evaluates performance and provides feedback); encouragement to act (the extent to which the organisation is driven by the achievement of its objectives); quality (the extent of the attention paid to quality procedures). |

Source: compiled by author

In addition to the dimensions of organisational climate already discussed, the dimensions of structure, responsibility, conflict, identity, risk, morale, managerial trustworthiness, resistance to change, stress and strain, adequate control, resource adequacy, clarity of responsibilities, and the importance of the external environment are also prominently used in research on organisational climate (Vos and Page, 2020; Afe et al. 2019). An analysis of the researchers’ work suggests that in order to measure the microclimate, the aim is to seek balance between the characteristics that best represent the organisation, their influence on the subjective experience of the individual and the subjective evaluation of the employee. It also supports the view that each organisation may have characteristics that are largely unique to it, which shape the individual’s unique experience of the organisation, influencing the individual’s own behaviour and, at the same time, determining the behaviour of the community working in the organisation.

Employee well-being: conceptualisation and expression

Although there are many attempts to define well-being in the academic literature, there is no unanimous consensus on how to conceptualise it. There are many prosaic or ambiguous descriptions in the work of authors, which include affective, cognitive and behavioural aspects (Kahtani and Sulphey, 2022). Well-being is defined as a phenomenon with links to a person’s material or spiritual values, his or her emotional states (Stankeviciene et al. 2021), a balance between the resources available to a person and the challenges in terms of the person’s abilities and their implications for the person’s performance and life projection (Elsamani et al. 2023). Also, well-being refers to the subjective (cognitive and emotional) ability to evaluate one’s life, which is associated with overall satisfaction, mood or sense of fullness (Sora, Caballer and García-Buades 2021). The concept of well-being has also been analysed from a subjective or objective perspective. Objective well-being refers to what a person needs to accumulate in order to survive (food, income, housing, education or health care system, community, infrastructure), while subjective well-being refers to a person’s evaluation of life based on feelings and thoughts (Salleh et al. 2020). The concept of well-being is most accurately described by distinguishing between two paradigms: hedonism and eudaimonism. Hedonism defines a subjective concept of well-being, which is related to the evaluation of one’s own quality of life in relation to the individual’s standards and emotional experiences. Eudaimonism proponents, by exaggerating the state of human psychological functions, propose the concept of psychological well-being, which is related to personal growth, self-acceptance, autonomy, and positive relationships with other people (Karapinar, Camgoz and Ekmekci 2020; Stankevičienė et al. 2021).

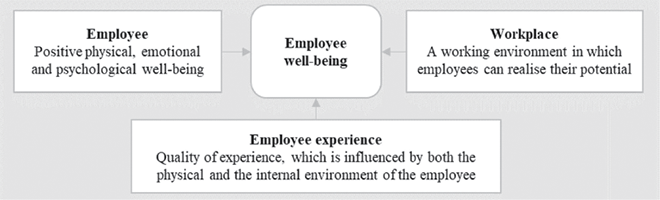

Just as well-being is associated with the internal and external environments of people, employee well-being has been described as a feeling derived from the intrinsic and extrinsic value of work (Kahtani and Sulphey 2022; Taj et al. 2020) argue that well-being is the totality that connects the feelings people feel in the organisation where they work with the work or activities they perform. It is also noted that when looking at employee well-being, it is important to take a comprehensive and holistic approach that focuses on how well employees feel and function in the organisation. However, Corrêa et al. (2019) contradict this by stating that positive feeling should not be confused with happiness, arguing that it is more about the prevalence of positive emotions in the organisation and the perceived overcoming of the employee’s potential to achieve individual goals. Although there is no consensus on the definition of employee well-being, scholarship focuses on the employee’s mindset in relation to individual experience, their ability to manage workload, control work, develop working relationships, actively participate in change, and their sense of satisfaction and interaction with stressors in the work environment (Khan et al. 2020). In addition, the role of employee well-being relates not only to the employee’s ability to realise his or her abilities in the work environment, but also to the organisation’s own performance by drawing attention to the synergy between the interests of the employee and the employer (Quifors, Chan and Dai 2021). A theoretical analysis of the work of researchers suggests that employee well-being is a positive physical, emotional and psychological state of an employee, where the employee perceives his or her life as meaningful and fulfilling, and that it is determined by a supportive work environment in which the employee is able to realise his or her individual capabilities. It is the quality of the employee’s experience, combining individual and organisational goals, which is influenced by both the physical and the internal environment of the employee.

Figure 2

Employee well-being definition

Source: compiled by author

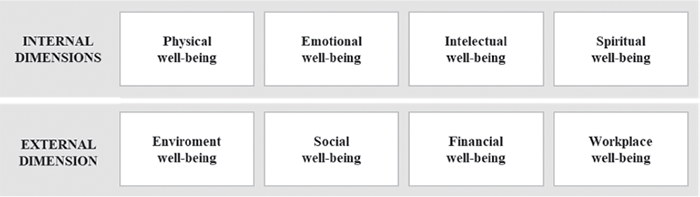

The dimensions of well-being are often linked to psychological dimensions, for example, Kahtani and Sulphey (2022) examine well-being through the lens of self-determination theory, arguing that it is determined by the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, social relationships). In addition, the authors highlight other factors related to psychological well-being, such as positive emotions, engagement, sense of meaning, individual achievement, job satisfaction, and involvement in activities. However, researchers agree that employee well-being is not solely influenced by psychological phenomena. In addition to this, other states such as physical, intellectual and spiritual states are also important Ahmad, Edvin and Bamber 2022; Nathan, 2022; Sorribes, Celma and Garcia, 2021) note the dimensions of happiness, health and social well-being. Their ideas are complemented by Quifors, Chan and Dai (2021), who jointly state that the dimension of happiness, which is also referred to as the psychological dimension, combines job satisfaction and human psychological characteristics that have implications for the harmonisation of working practices, work–life balance, productivity, and relations with colleagues. The health dimension is characterised by objective physical parameters, such as physical fitness or how stress factors affect the worker. The social dimension is defined by the relationship between managers and employees, trust, reciprocity, cooperation and support. Akanni, Kareem and Oduaran (2020) measured employee well-being in their study by dividing it into three dimensions of job fatigue, general health and job engagement. To measure the dimension of work fatigue, the authors used indicators of physical fatigue, mental fatigue and emotional fatigue. General health was measured by indicators defining social dysfunctionality, while work engagement was measured by indicators of vigour, commitment and engagement. According to another approach, the psychological dimensions of employees include factors such as the employee’s learning process, his/her sense of autonomy, his/her feelings of stress, individual goals, and recreation. The physical dimension is also added by including the employee’s illnesses, eating habits, lifestyle and physical activity, which are related to the overall physical condition of the person. In addition, the social dimension is expanded by focusing on the phenomenon of volunteering, links with the community, family, friends and colleagues. Researchers add another dimension, that of environmental factors, which includes the parameters of lighting, appropriate temperature, comfort level, air quality (Suwarnajote and Mekhum, 2020). Although there are various attempts to distinguish the dimensions of employee well-being, in some cases the descriptive terms are synonymous with each other. For example, the psychological dimension is equated with the emotional dimension and relates to general mental health, feelings of satisfaction, stress or anxiety. In addition, there is a financial perspective, which describes anxiety about the current financial situation, financial problems, and financial uncertainty in the future, which has a negative impact on the employee’s well-being (Beck-Krala, 2022). In addition, researchers also point to psychosomatic (the importance of internal influences on physiological processes), affective (satisfaction, mood, commitment to the organisation, emotional exhaustion), cognitive (cognitive fatigue, concentration, ability to take in new information), and occupational (autonomy, individual aspirations, competence) dimensions (Platts, Breckon and Marshall, 2022). Gorgenyi-Hegyes, Nathan and Fekete-Farkas (2021) examine eight dimensions by dividing them into two perspectives (see Figure 3). This approach has the characteristic of contradicting the distinctions between the dimensions of employee well-being discussed so far. In the latter, the financial or social dimensions are viewed from the internal perspective of the human environment, whereas in this case they are classified as external, but it can be argued that the authors’ insights summarise the dimensions of employee well-being that have been discussed so far.

To summarise the researchers’ work, the dimensions of employee well-being are examined through the perspectives of the physical and nonphysical aspects of the individual, the work environment and the relationships with other people, and the factors that determine them. Employee well-being is determined by the organisations that shape the work-related activities that enable the employee to use his or her skills and competences and by the environment that affects the people who work there. Also, by the social relationships that the employee develops with people in the work environment or elsewhere. And finally, by the worker himself, whose physical, mental or emotional state determines his ability to perform in the work environment.

Figure 3

Internal and external well-being dimensions

Source: Gorgenyi-Hegyes, Nathan and Fekete-Farkas, 2021

Expression of violence in the workplace

Research on violence in the workplace is complex, due to the difficulty in defining the concept of violence. There are many definitions and theoretical differences related to violence, but in order to reach a consensus, some authors use a generalised definition of workplace violence that applies to different forms of violence, given that its constituent elements can be diverse and different (Civilotti, Berlanda and Iozzino, 2021). On the other hand, other descriptions such as ‘intimidation,’ ‘bullying,’ ‘psychological violence,’ ‘harassment,’ ‘psychoterrorism,’ ‘bullying’ can also be encountered in scientific works (İbiloğlu 2020, 332). When analysing the definitions of violence in the workplace, one important aspect emerges, which is that the definitions denote an act that is directed against another person, given that bullying is a deliberate attempt to harm another, and also, its effects encompass physical, psychological or sexual harm (Civilotti, Berlanda and Iozzino, 2021), (Stahl-Gugger and Hämmig, 2022). In addition, the perspective of the perpetrator is also relevant and can be used to categorise violence into four types: violence perpetrated by individuals who are not connected to the workplace; violence perpetrated by visitors, clients or family members of the organisation; violence perpetrated by a current or former employee of the same organisation; and violence perpetrated by an individual with whom the victim has an informal relationship outside of work (Pacheco et al. 2021; Hsu, Chou and Ouyang, 2022; Barros et al. 2022; Somani et al. 2021). This approach is complemented by the distinction between two types of workplace violence: the horizontal type, in which the perpetrator is a colleague, a member of the same organisation, and the vertical type, in which the perpetrator is a supervisor or a person in a higher position (Caillier, 2021). It is important to note not only that the phenomenon of violence combines the interaction between the perpetrator and the victim of violence, but also the actions by which the perpetrator’s work negatively affects others. In this respect, Barros et al. (2022) note that the most popular forms of violence used in the work environment are verbal violence, intimidation of others and physical aggression against others. Some authors expand on nonphysical forms of violence by stating that they are: verbal, active, passive, direct, indirect. In general, nonphysical aggression is characterised by intimidation, belittling and singling out the victim from others. It is also defined as deliberate verbal or nonverbal behaviour that is intended to intentionally harm another employee of the organisation (Pacheco et al. 2021). A similar approach is followed in the purification of other forms of workplace violence. Caillier (2021) argues that violence in the work environment can be physical, verbal, active, passive, direct and indirect. In this case, physical and verbal violence are strictly distinguished through harm, with physical violence involving physical harm and verbal violence nonphysical harm. Active aggression is also interpreted as actions that cause direct harm to others, while passive aggression refers to the deliberate omission of actions, thus causing indirect negative effects. Direct aggression includes direct actions such as shouting, screaming or threatening the victim, while indirect aggression refers to attacks on the victim that are carried out indirectly, for example, by spreading false rumours without the victim knowing.

In analysing the definition of workplace violence, it is worth noting the concept of mobbing, which was first mentioned by Konrad Lorenz, a scientist who studied aggressive behaviour in animals, where weaker animals use a form of aggressive behaviour to intimidate and deal with stronger rivals. In the study of human social relations, the term was first used to describe the behaviour of schoolchildren, who used aggression against others who they perceived to be lonely and weak. This was first noted by Peter-Paul Heinemann (İbiloğlu, 2020). Research reveals that mobbing is not a random phenomenon, it is rooted in the conflict between the victim and the aggressor, and that this form of violence is characterised by continuity, in which the aggressive behaviour is repeated more than once. Researchers also argue that mobbing is characterised by an imbalance of power, whereby the person who is attacked is weaker or less able to defend themselves. In addition, acts of violence are repeated over and over again with the aim of getting rid of the victim or putting pressure on the victim to leave the job (Acquadro Maran et al. 2022).

There are two perspectives on mobbing – vertical and horizontal. Vertical mobbing manifests from the top down, where a manager uses his or her position of professional power to target subordinates or employees in lower positions. On the other hand, vertical mobbing from the bottom up is manifested by the unionisation of workers, where more than one member is involved in violence against the manager or a superior, thereby increasing the power imbalance. Horizontal mobbing occurs between employees who hold the same or similar positions (Vveinhardt and Sroka 2020). Researchers agree that the occurrence of mobbing in an organisation is not static, but changes over time, and in analysing this, several views can be identified, the first of which describes the following sequence: conflict between the aggressor and the victim; a phase of aggressive actions; involvement or intervention by management; spreading false rumours about the victim; dismissal or exit. Another view identifies the following stages: spreading false rumours about the victim and alienating other employees; avoiding or singling out the person from the crowd; discriminating against and stigmatising the victim; and physical attacks on the victim (İbiloğlu, 2020). In addition to this, the authors divide mobbing into three levels of severity, according to the severity of the consequences for the victim. The first level includes mild aggressive attacks that can be resisted, the second level causes physical and psychological problems for the victim and as a result the victim is no longer in a position to resist the attacks, and the third level leads to serious negative consequences that result in the victim not being able to continue working in the same working environment (İbiloğlu, 2020). When investigating the acts of violence characteristic of mobbing cases, 45 acts of psychological violence can be identified, which are usually divided into five categories: Impact through social relationships and exclusion or isolation of the victim; attack in the field of communication, manifested by restriction of the victim’s ability to express his/her opinion and constant criticism; disparagement of reputation and spreading false rumours about the victim; damage to occupational or quality of life, in the form of actions that cause anxiety, stress, frustration or reduce the victim’s work performance; potential damage to health, in the form of forcing the victim to work in harmful conditions or in the form of sexual or physical acts (Dopelt et al. 2022; Vveinhardt and Sroka 2020). To summarise the insights of the authors mentioned above, workplace violence is any behaviour that has a negative impact, which is manifested by physical action, harassment, bullying or any other threatening behaviour that takes place in the work environment. Violence may include threatening others, verbal or nonverbal abuse, physical assault, physical or nonphysical harm to health, etc. It can also involve an organisation’s employees, its customers, visitors or their relatives and can be associated with descriptions such as harassment, bullying, mobbing, psychological violence, hostility, sabotage, stalking, etc. (Zhou, Rasool and Ma, 2020; Ghareeb, El-Shafei and Eladl, 2021).

The links between microclimate, employee well-being and workplace violence

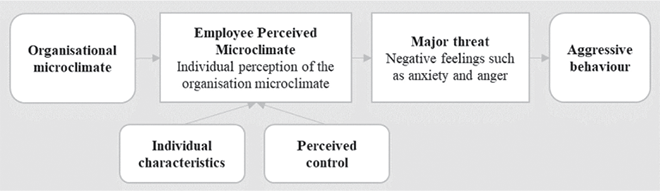

According to Maidaniuc-Chirilă (2020), the relationship between the organisational climate and violence in the work environment can be analysed through the “stress and emotional factors theory.” This theory explains the occurrence of violence in the work environment through the individual’s emotional response to stressful circumstances related to the work environment. Each individual perceives the organisational environment differently and, depending on individual characteristics and perceived control over environmental factors, the individual subjectively assesses the threats associated with the organisational microclimate. Negative feelings such as anger or anxiety arise when the perceived threat is high and this triggers physical and psychological tension and aggressive behaviour.

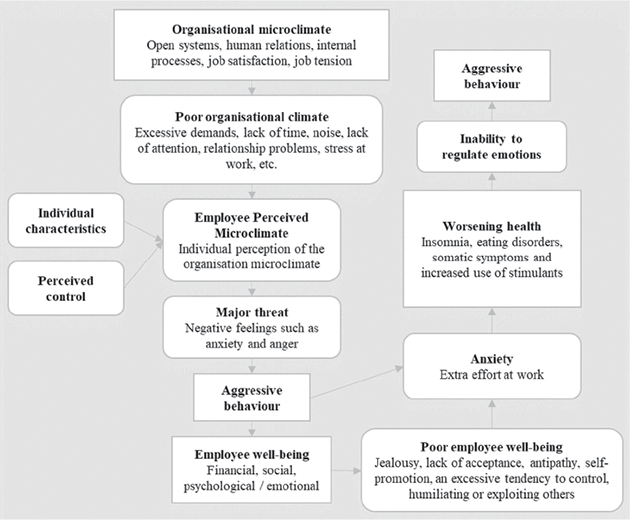

Figure 4

Stress and emotional factors theory

Source: Maidaniuc-Chirilă, 2020.

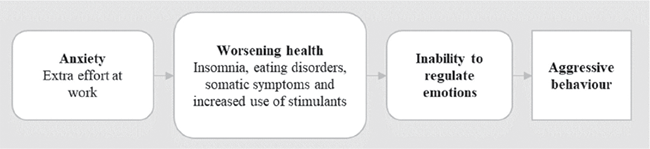

Researchers agree that, just as violence has a role in the stress experienced by workers, so too does stress in the work environment have a role in the occurrence of violence in the workplace. Stress is associated with role ambiguity, conflict situations between employees, and excessive workload. It is also argued that this not only has a negative impact on employees, but also forces them to redirect their efforts away from their work tasks and towards trying to cope with the stressors present in their environment (Caillier, 2021). This is partly supported by Hsu, Chou and Ouyang (2022) when they identify the main reasons for the occurrence of violence in the work environment. According to the authors, workplace violence is caused by excessive and frequent contact with customers, insufficient staffing levels and the resulting excessive workload, high job demands, lack of time to complete tasks, excessive noise, lack of attention and care, relationship problems, lack of effective programmes to prevent workplace violence, and the absence of a protective policy or regulation. Taken together, these authors suggest that the causes of violence in the workplace can be linked to dimensions of the organisational climate. For example, staff shortages, workload problems and demands can be linked to the open systems dimension, lack of attention or care can be linked to the human relations dimension, and the absence of preventive programmes or protective policies can be linked to the internal processes dimension. Barros et al. (2022) add to this by explaining that the increase in cases of violence is due to the excessive pace of work, emotional demands, the stress experienced by employees, poor interpersonal relations, lack of information and resources, and socio-economic constraints. On the other hand, the causes of workplace violence may be linked not only to the work environment but also to individual problems. For example, İbiloğlu (2020) points to the role of childhood trauma in violence against others, as well as jealousy, feelings of organisational injustice, lack of need for recognition, social inadequacy, dislike of other individuals or some of their characteristics, inadequate managerial behaviour or leadership, low moral standards or problems with the reward system. These causes of violence in the workplace can be linked to dimensions of employee well-being, such as: the financial dimension, where the employee is worried about his/her current financial situation; the social dimension, which refers to the need for a sense of trust or recognition; and the psychological/emotional dimension, which refers to the anxiety or stress that is experienced. In elaborating on these insights, it is also important to mention the traits attributed to violent aggressors, such as neurotic self-aggrandisement and an exaggerated tendency towards control. In this respect, the narcissistic behaviour of violent managers in their daily activities is also examined, as it becomes an important factor contributing to the emergence of violence in the work environment and hostility towards each other. Alhasnawi and Abbas (2021) point out that narcissistic managerial behaviour is characterised by dividing employees into groups and exploiting them for selfish purposes, thus slowly creating a gap between employees, aggression towards each other and a hostile atmosphere. Narcissistic managers are also characterised by public humiliation and ridicule of others, and are reluctant to accept criticism, but tend to display dominance, arrogance and exaggeration of their own opinions. In addition to a lack of empathy, they are also characterised by manipulation of others, abuse of power by withholding information and belittling others (Aboramadan et al. 2020). Looking at the authors’ insights, it is important to note that this is not only linked to the emergence of aggressive behaviour in the work environment, but also to its further spread, where rude behaviour towards others creates its proliferation. According to Maidaniuc-Chirilă (2020), this is explained by the ‘nervous exhaustion theory,’ which draws attention to the consequences of rude behaviour. When a person is exposed to continuous rude behaviour, the same person who is subjected to rude behaviour eventually develops a propensity to violence. Initially, the person experiences mild anxiety, which requires extra effort to concentrate on the normal pace and rhythm of work, as well as insomnia, poor health, eating disorders and a possible increase in stimulant use. As these problems worsen, the person is unable to regulate his or her emotions, leading to hostile, aggressive behaviour towards others.

Figure 5

The theory of nervous exhaustion

Source: Maidaniuc-Chirilă, 2020

In this context, it is also important to analyse the consequences of workplace violence, which contribute to the further spread of violence. On the one hand, violence is linked to the decision of workers to leave their jobs and seek more favourable working conditions. However, looking at scholarly work, it is evident that a worker’s decision to leave in the presence of violence does not always refer to the fact of leaving itself; it may only refer to the worker’s decision to leave the employer, and the actual departure occurs within a period of one or two years (Caillier 2021; Pacheco et al. 2021; Somani et al. 2021). Also, violence negatively affects employee loyalty, threatens employee well-being and, given the definitions of well-being, it can be argued that violence negatively affects an employee’s interaction with the work environment around them (Alhasnawi and Abbas, 2021; Rasool et al. 2020; Wech, Howard and Autrey, 2020; Dnyaeshwar and Rajpoot, 2010). These insights are complemented by the assertion that violence in the work environment reduces the employee’s ability to adapt to the environment, increases the risk of burnout, increases the employee’s isolation, and causes stress for the employee, as well as, encourages the employee to be violent towards others (Acquadro Maran et al. 2022; Schablon et al. 2022). In addition, there are also negative economic implications for both the employees who are subjected to violence (job search costs, legal services, insurance costs, medication, psychological counselling) and the organisations themselves (reduced productivity, reduced quality of work performance, compensation for damages) (İbiloğlu 2020; Gembalska-Kwiecień, 2020). Violence also has implications for the quality of life and problems of workers. It has been observed that violence in the work environment is associated with an increase in anxiety or distrust of other people, and that people who experience violence tend to use tobacco more often, experience increased emotional fatigue, increased feelings of fear, decreased job satisfaction and decreased motivation. In addition, the negative consequences of violence in the workplace can also affect other areas of a person’s life, such as social relationships, where psychological distancing leads to increased conflict at work and at home (Savoy et al. 2021; Pacheco et al. 2021). Research also shows that psychological violence is closely linked to health problems, reduced self-confidence, and various mental disorders. Victims of violence are more likely to experience feelings of indifference, hostility, depression, anxiety, helplessness, irritability, intolerance of others, sleep disturbances, reduced attention span, and reduced self-esteem. In addition, studies have also revealed psychosomatic phenomena experienced by victims of violence, such as chronic pain syndrome or asthma attacks (Nyberg et al. 2020; Jeong and Lee, 2020; Vveinhardt and Sroka, 2020). An analysis of the research literature suggests that the consequences of violence in the workplace can be divided into six categories: physical, such as physical injuries; psychological, such as depression or burnout; emotional, such as anxiety; functioning at work, such as loss of earning capacity; social, such as family conflicts; and economic, such as the loss of resources after losing one’s job (Stahl-Gugger and Hämmig, 2022).

Figure 6

Organisational climate role on employee well-being and the occurrence of workplace violence

Source: compiled by author

As we can see (Figure 6) in this context, it is important to identify the following dimensions of the microclimate: open systems, human relations, internal processes, job satisfaction, and job strain (Diab, Diab and Emam, 2021; Mueller and Surachaikulwattana, 2020; Barría-González et al. 2021; Tadesse, 2019; Michalak, 2019; Vos and Page, 2020; Afe et al. 2019). Poor organisational climate indicates the presence of problems in an organisation, such as excessive and frequent contact with customers, insufficient staffing levels, excessive workload, high job demands, lack of time to complete tasks, high noise levels, lack of attention, social relationship problems, stress experienced by employees, and socio-economic constraints (Caillier, 2021; Hsu, Chou and Ouyang, 2022). These problems can be linked to the negative implications for employees’ perceptions of the organisational microclimate and the threats associated with it, which, given employees’ individual characteristics and perceived control, can lead to aggressive behaviour towards others inside and outside the work environment Maidaniuc-Chirilă (2020). On the other hand, it is also possible to distinguish the association of poor employee well-being with the occurrence of violence in the work environment. In this case, it is necessary to distinguish the financial, social, psychological/emotional dimensions of employee well-being (Suwarnajote and Mekhum, 2020; Beck-Krala,2022; Gorgenyi-Hegyes, Nathan and Fekete-Farkas, 2021). Negative employee well-being, by its very nature, can indicate individual problems such as jealousy, feelings of organisational injustice, lack of recognition, antipathy, self-aggrandizement, an exaggerated tendency to control, and the humiliation or exploitation of others (Alhasnawi and Abbas, 2021; Aboramadan et al. 2020). These problems may not only contribute to the emergence of violence in the workplace, but also to its further spread, where workers who are subjected to persistent harsh behaviour eventually experience physical, emotional and psychological problems that negatively affect the individual’s ability to regulate emotions and lead to aggressive behaviour with others (Maidaniuc-Chirilă, 2020).

Conclusions and implications

This study provides insights that summarise the scholarly debate on organisational climate, employee well-being and workplace violence. The findings of this paper showed that poor organisational climate has been found to have a negative impact on employee’s experiences and perceptions of the work environment. Depending on the individual’s internal factors, a poor microclimate can lead to negative emotions such as anxiety or anger, as well as to the emergence of aggressive behaviour in employees’ social relationships. At the same time, a poor organisational climate has a negative impact on the well-being of employees, the deterioration of which has a negative impact on the health of employees, on their ability to regulate their emotions, and on the further spread of violence in the organisation. Although being aware, that the results of this paper show theoretical constructs, the insights will enable organisations owners and managers to pay attention to the importance of the organisation’s microclimate for assessing and addressing the challenges of employee well-being and workplace violence. In addition, this paper makes valuable contribution to further empirical research development, as it provides a clearer picture of the studied phenomena and their manifestation.

References

Aboramadan, M., Türkmenoğlu, M. A., Dahleez, K. A., & Çiçek, B. (2020). Narcissistic leadership and behavioral cynicism in the hotel industry: the role of employee silence and negative workplace gossiping. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(2), 428–447. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/0959-6119

Maran, D. A., Varetto, A., Civilotti, C., & Magnavita, N. (2022). Prevalence and Consequences of Verbal Aggression among Bank Workers: A Survey into an Italian Banking Institution. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 78-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030078

Ahmad, A., Aimal Edwin C. E., Bamber, D. 2022. Linking Relational Coordination and Employees’ Wellbeing through Psychological Capital. Journal of Managerial Sciences, 69(2), 68–88. https://journals.qurtuba.edu.pk/ojs/index.php/jms/article/view/594

Akanni, A. A., Kareem, D. B., & Oduaran, C. (2020). The relationship between emotional intelligence and employee wellbeing through perceived person-job fit among university academic staff: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1869376

Kahtani, N. S. A., & Sulphey, M. M. (2022). A study on how psychological capital, social capital, workplace wellbeing, and employee engagement relate to task performance. SAGE Open, 12(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221095010

Alhasnawi, H. H., & Abbas, A. A. (2021). Narcissistic leadership and workplace deviance: a moderated mediation model of organizational aggression and workplace hostility. Organizacija, 54(4), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2021-0023

Barría-González, J., Postigo, Á., Pérez-Luco, R., Cuesta, M., & García‐Cueto, E. (2021). Assessing Organizational Climate: Psychometric properties of the ECALS Scale. Anales De Psicologia, 37(1), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.417571

Barros, C., Meneses, R. F., Sani, A. I., & Baylina, P. (2022). Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Work-Related Predictors of Violence Behaviours. Psych, 4(3), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030039

Bayhan Karapinar, P., Metin Camgoz, S. & Tayfur Ekmekci, O. (2019). Employee Wellbeing, Workaholism, Work–Family Conflict and Instrumental Spousal Support: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(7), 2451–2471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00191-x

Beck-Krala, E. (2022). Employee well-being from the perspective of human resources professionals. Scientific papers of silesian university of technology. Organization and management series, 159, 27–37. 10.29119/1641-3466.2022.159.2

Brunetto, Y., Saheli, N., Dick, T., & Nelson, S. A. (2021). Psychosocial safety climate, psychological capital, healthcare SLBs’ wellbeing and innovative behaviour during the COVID 19 pandemic. Public Performance & Management Review, 45(4), 751–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1918189

Caillier, J. G. (2020). The impact of workplace aggression on employee satisfaction with job stress, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intentions. Public Personnel Management, 50(2), 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026019899976

Civilotti, C., Berlanda, S., & Iozzino, L. (2021). Hospital-Based Healthcare Workers Victims of Workplace Violence in Italy: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(11), 5860-5877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115860

Corrêa, J. S., Lopes, L. F. D., De Almeida, D. M., & Camargo, M. E. (2019). WORKPLACE WELLBEING AND BURNOUT SYNDROME: OPPOSITE FACES IN PENITENTIARY WORK. RAM. Revista De Administração Mackenzie, 20(3), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-6971/eRAMG190149

D’Amato, A. (2023). From research to action and back again: The long journey of organizational climate – A review of the literature and a summative framework. Journal of General Management, 0(0), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063070231152010

Thi Mai Huong, D., Tran, T. T. H., Tran, A.H. (2021). High-performance human resource management practices and creative organizational climate effects on manufacturing industry performance. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 23(2), 72–89. https://pjms.zim.pcz.pl/api/files/view/1669265.pdf

Diab, A., H. M., Emam., D. H. (2021). How Does Organizational Climate Contribute to Job Satisfaction and Commitment of Agricultural Extension Personnel in New Valley Governorate, Egypt?. Alexandria Science Exchange Journal, 42(3), 749–59. https://dx.doi.org/10.21608/asejaiqjsae.2021.193596

Dnyaeshwar, P. D., Rajpoot, J. (2022). Recommendations for Management Rules and Controls of Workplace Violence against the Nursing Staff in Emergency Workplace. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 13(6), 2109–21. https://doi.org/10.47750/pnr.2022.13.S06.275

Dopelt, K., Davidovitch, N., Stupak, A., Ayun, R. B., Eltsufin, A. L., Levy, C. (2022). Workplace Violence against Hospital Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Israel: Implications for Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4659–71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084659

Elsamani, Y., Mejia, C., Kajikawa, Y. (2023). Employee Well-Being and Innovativeness: A Multi-Level Conceptual Framework Based on Citation Network Analysis and Data Mining Techniques. PLOS ONE, 18(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280005

Gembalska-Kwiecień, A. (2020). Mobbing Prevention as One of the Challenges of a Modern Organization. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology Organization and Management Series, 2020 (144), 71–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2020.144.6

Ghareeb, N. .S., El-Shafei, D. A., Eladl. A. M. (2021). Workplace Violence among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic in a Jordanian Governmental Hospital: The Tip of the Iceberg. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(43), 61441–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15112-w

Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E., Nathan, R. J., Fekete-Farkas, M. (2021). Workplace Health Promotion, Employee Wellbeing and Loyalty during Covid-19 Pandemic—Large Scale Empirical Evidence from Hungary. Economies, 9(2), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9020055

Hsu, M., Chou, M., Ouyang, W. (2022). Dilemmas and Repercussions of Workplace Violence against Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2661–2677. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph19052661

Afe, C. E. I., Abodohoui, A., Mebounou, T. G. C., & Karuranga, E. (2018). Perceived organizational climate and whistleblowing intention in academic organizations: evidence from Selçuk University (Turkey). Eurasian Business Review, 9(3), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-018-0110-3

Jackson, J., Harper, N., McLean, S. (2021). Trust, Workload, Outdoor Adventure Leadership, and Organizational Safety Climate. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 13(4), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.18666/JOREL-2020-V13-I4-10529

Jeong, Y., Lee, K. (2020). The Development and Effectiveness of a Clinical Training Violence Prevention Program for Nursing Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4004–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114004

Kakhki, M. K., Hadadian, A., Joyame, E. N., & Asl, N. M. (2020). Understanding librarians’ knowledge sharing behavior: The role of organizational climate, motivational drives and leadership empowerment. Library & Information Science Research, 42(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.100998

Kessler, S. R. (2019). Are the Costs Worth the Benefits? Shared Perception and the Aggregation of Organizational Climate Ratings. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(9), 1046–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2415

Khadivi, A., Gavgani, A. N., Khalili, M. R., Sahebi, L., & Abouhamzeh, K. (2019). Is there a relationship between organizational climate and nurses’ performance? Exploring the impact with staff’s satisfaction as the mediator. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(2), 424–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2019.1656859

Khan, S., Singh, J., Singh, K., Kaur, D., Arumugam, T. (2020). Mindfulness in an Age of Digital Distraction and the Effect of Mindfulness on Employee Engagement, Wellbeing, and Perceived Stress. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 12(3), 77–86.

Köllen, T., Koch, A., Hack, A. (2019). Nationalism at Work: Introducing the ‘Nationality-Based Organizational Climate Inventory’ and Assessing Its Impact on the Turnover Intention of Foreign Employees. Management International Review, 60(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-019-00408-4

Li, F., Liang, X. Liu, Q. (2022). Applying Attachment Theory to Explain Boundary-Spanning Behavior: The Role of Organizational Support Climate. Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo Y de Las Organizaciones, 38(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a13

Maidaniuc-Chirilă, T. (2020). Workplace Bullying Phenomenon: A Review of Explaining Theories and Models. Annals of the „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University, Psychology Series, 29, 63–85.

Michalak, J. M. (2019). Project managers’ individual temporal perspective and positive organizational climate: an empirical investigation. Journal of Positive Management, 10(3), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.12775/JPM.2019.009

Salleh, E. S. M., Mansor, Z. D., Zainal, S. R. M., & Yasin, I. M. (2020). Multilevel analysis on employee wellbeing: the roles of authentic leadership, rewards, and meaningful work. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 25(1), 123-146. https://doi.org/10.21315/aamj2020.25.1.7

Mueller, L. A., Surachaikulwattana, P. (2020). The influence of cultural differences on human relation aspects of organizational climate and job satisfaction. UTCC International Journal of Business and Economics, 12(3), 89–108. http://ijbejournal.com/images/files/1681600415611ccf0addc35.pdf

Nathan, G. (2022). Meaningfulness at Work: Wellbeing, Employeeship and Dignity in the Workplace. The IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 18(2), 16–42.

Nyberg, A., Kecklund, G., Hanson, L. L. M., & Rajaleid, K. (2020). Workplace violence and health in human service industries: a systematic review of prospective and longitudinal studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 78(2), 69–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-106450

OKAN İBİLOGLU, A. (2020). Farklı Yönleriyle Mobbing (Psikolojik Şiddet). Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar - Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 12(3), 330–41. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.543354

Osmani, F., Sejdiu, S., Jusufi, G. (2022). Organizational Climate and Job Satisfaction. Management, 27(1), 361–77. https://doi.org/10.30924/mjcmi.27.1.20

Ozsoy, T. (2022). The Effect of Innovative Organizational Climate on Employee Job Satisfaction. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 2(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2022.2-01

Pacheco, E., Bártolo, A., Rodrigues, F. P., Pereira, A., Duarte, J., & Da Silva, C. F. (2021). Impact of psychological aggression at the workplace on Employees’ health: A Systematic Review of Personal Outcomes and Prevention Strategies. Psychological Reports, 124(3), 929–976. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119875598

Platts, K., Breckon, J., Marshall, E. (2022). Enforced Home-Working under Lockdown and Its Impact on Employee Wellbeing: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12630-1

Ponting, S. S. (2019). Organizational Identity Change: Impacts on Hotel Leadership and Employee Wellbeing. The Service Industries Journal, 40(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1579799

Quifors, S., Chan, J. Y., Dai, B. (2021). Workplace Wellbeing during Covid-19: Aotearoa New Zealand Employers’ Perceptions of Workplace Wellbeing Intiatives and Their Limitations. New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research, 17(2), 1–18. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.266240858744738

Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Zhang, Y., & Samma, M. (2020). Sustainable Work Performance: The roles of workplace violence and occupational stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 912-924. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph17030912

Rimbayana, T. a. K., Erari, A., & Aisyah, S. (2022). The influence of competence, cooperation and organizational climate on employee performance with work motivation as a mediation variable (Study on the Food and Agriculture Office Clump of Merauke Regency). Technium Social Sciences Journal, 27, 556–578. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v27i1.5200

Roberge, M., Xu, Q. J., Aydin, A. L., Huang, W. (2021). An Inclusive Organizational Climate: Conceptualization, Antecedents, and Multi-Level Consequences. American Journal of Management, 21(5), 97–115. https://articlearchives.co/index.php/AJM/article/view/1581

Savoy, S., Carron, P., Romain-Glassey, N., & Beysard, N. (2021). Self-Reported violence experienced by Swiss prehospital emergency care providers. Emergency Medicine International, 2021, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155%2F2021%2F9966950

Schablon, A., Kersten, J. F., Nienhaus, A., Kottkamp, H., Schnieder, W., Ullrich, G., Schäfer, K., Ritzenhöfer, L., Peters, C., & Wirth, T. (2022). Risk of Burnout among Emergency Department Staff as a Result of Violence and Aggression from Patients and Their Relatives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 4945-1960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094945

Somani, R., Muntañer, C., Hillan, E., Velonis, A. J., & Smith, P. M. (2021). A Systematic Review: Effectiveness of Interventions to De-escalate Workplace Violence against Nurses in Healthcare Settings. Safety and Health at Work, 12(3), 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2021.04.004

Sora, B., Caballer, A. M., García-Buades, E. (2021). Human Resource Practices and Employee Wellbeing from a Gender Perspective: The Role of Organizational Justice. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 53 (November), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2021.v53.5

Sorribes, J., Celma, D., Martínez‐Garcia, E. (2021). Sustainable Human Resources Management in Crisis Contexts: Interaction of Socially Responsible Labour Practices for the Wellbeing of Employees. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(2), 936–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2111

Stahl-Gugger, A., & Hämmig, O. (2022). Prevalence and health correlates of workplace violence and discrimination against hospital employees – a cross-sectional study in German-speaking Switzerland. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07602-5

Stankevičienė, A., Tamaševičius, V., Diskienė, D., Grakauskas, Ž., & Rudinskaja, L. (2021). The Mediating Effect of Work-Life Balance on the Relationship between Work Culture and Employee Well-Being. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 22(4), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2021.14729

Suwarnajote, N., Mekhum, W. (2020). The Impact of Human Resource Practices on Employee Wellbeing of the Pharmacy Firms in Thailand. Systematic Review Pharmacy, 11(1), 425–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.5530/srp.2019.2.04

Tadesse, W. M. (2019). The Interface between Organizational Climate and Work Passion: A Case Study of Selected Private Institutions in Ethiopia. Journal of IMS Group, 16(1), 1–13.

Taj, A., Ali, S., Zaheer, Z., Gul, M. (2020). Impact of Envy on Employee Wellbeing: Role of Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 30(2), 97–117.

Tantaru, O., Schmitz, L. M., Moasa, H. (2021). The impact of emotional intelligence on organizational climate. Series VII - social sciences and LAW, 14(63) (1), 89 –100. https://doi.org/10.31926/but.ssl.2021.14.63.1.9

Vévodová, Š., Vévoda, J., Grygová, B. (2020). Mobbing, Subjective Perception, Demographic Factors, and Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Nurses. Central European Journal of Public Health, 28 (October), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a6211

Vos, L., & Page, S. J. (2020). Marketization, performative environments, and the impact of organizational climate on teaching practice in business schools. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 19(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2018.0173

Vveinhardt, J., Sroka, W. (2020). Innovations in Human Resources Management: Instruments to Eliminate Mobbing. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 2, 182–95. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6231-9402

Wardono, G., Moeins, A., Sunaryo, W. (2022). Influence of Organizational Climate on OCB and Employee Engagement. Journal of World Science, 1(8), 560–69. https://doi.org/10.58344/jws.v1i8.77

Weber, W., Unterrainer, C., & Schmid, B. E. (2009). The influence of organizational democracy on employees’ socio-moral climate and prosocial behavioral orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(8), 604-616.

Wech, B. A., Howard, J., Autrey, P. (2020). Workplace Bullying Model: A Qualitative Study on Bullying in Hospitals. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 32(2), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-020-09345-z

Xu, Z., Wang, H., & Suntrayuth, S. (2022). Organizational climate, innovation orientation, and innovative work behavior: the mediating role of psychological safety and intrinsic motivation. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2022, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9067136

Zhou, X., Rasool, S. F., & Ma, D. (2020). The Relationship between Workplace Violence and Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Employee Wellbeing. Healthcare, 8(3), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fhealthcare8030332