Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2023, vol. 13, pp. 183–199 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2023.13.21

Linking Company’s Activity and Human Well-Being from the Perspective of Corporate Social Responsibility

Izolda Skruibytė

Klaipėdos valstybinė kolegija / Higher Education Institution, Lithuania

i.skruibyte@kvk.lt

https://orcid.org/000-0001-6057-1305

Abstract. There is growing interest from academic scholars and international institutions in assessing the impact of business activity on human well-being. Business is essential for our lives but it is still unclear what companies’ activities should be to increase standards of living and to contribute better to higher human well-being. What is the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on human well-being, and how can companies be motivated towards more responsible activities? Partly, it is a matter of subjective understanding and, partly, a matter of assessing the phenomena of human well-being and CSR tends to make these relations more complicated and more scientific discussions are needed, therefore, to address these issues. The present study represents a comprehensive analysis of the concept of human well-being from the perspectives of both hedonic and eudaimonic approaches and it also investigates the role of CSR in companies’ economic activities, as well as outlines the theoretical links between CSR and human well-being. A conceptual model of the links between company’s economic activity and human well-being, according to CSR, is provided. The model states that the contribution of a business to human well-being differs depending on whether company’s activity is concentrated on economic results, or rather on sustainable development. The responsible activity of a company that meets the environmental, social, and economic challenges when producing goods and providing services contributes positively to human well-being in the long term. CSR contributes to society by enabling companies to satisfy the expectations of society and it also strengthens the likelihood that a society can achieve higher living standards and sustainable development as well.

Keywords: corporate social responsibility; human well-being; life satisfaction; economic welfare.

Received: 2023-08-20. Accepted: 2024-01-20.

Copyright © 2023 Izolda Skruibytė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The concepts of social responsibility and well-being are not new in academic literature. Very reservedly, certain forms of corporate social responsibility as dimensions of the social and moral duties of business towards the community in which it operates have been mentioned in A. Smith’s famous work “The Wealth of Nations.” By the middle of the 20th century, however, the main focus of research was on the creation and rapid development of industry and the achievement of economic results, rather than on social issues. The second part of the 20th century can be distinguished as a period during which an incredible development of information technologies was achieved and, at the same time, as a period of growing social and environmental problems. Even though some economists reject the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Friedman, 1970; Levitt, 1958), the relevance and dynamics of economic, social, political, and other processes led to researchers giving increasing attention to CSR as a result of its potential impact on maintaining the sustainable growth of a country and on creating greater well-being in that country (Oluyemi et al., 2016; Carpion and Avramchuk, 2017; Kim et al., 2018).

The concept of well-being had been mentioned by Aristotle and other Greek philosophers even in ancient times. The well-being of humanity was always relevant for scientists and it remains the main issue of economics as a science, despite the fact that, very often, global disasters, wars and different economics problems prevented scientists from paying sufficient attention to developing this concept. It is for this reason, perhaps, that the authors of the latest academic papers still state that well-being is a dynamic process that depends from the free will of people (Roy, 2018), that the concept is something intangible (Thomas, 2009), or difficult to define precisely, and that it stays at the intuitive level (White, 2010) or that there is still confusion about what it means (Lee and Kim, 2015). According to Dodge et al. (2012), all previous authors have more focused on the dimensions and descriptions of well-being than on its various definitions.

Grant et al. (2007) emphasize the multidimensional nature of well-being. Well-being can be defined at different levels, such as the individual or social levels; it can be influenced by positive and negative things, and, therefore, according to Veronese et al. (2017), it can be reflected upon using objective or subjective indicators, which may be either one-dimensional or multidimensional. So, integrated research and analysis strategies should be applied to the investigation of this phenomenon.

Existing studies underline the importance of CSR on well-being (Carpion and Avramchuk, 2017), but a gap in our understanding of this relationship still exists and further research is needed in both theoretical and empirical fields. Every country is striving for higher economic growth to ensure the welfare of its people. Economic activity creates welfare but higher economic welfare does not necessarily reflect higher social well-being (Briguglio, 2019). Relying on data from the US National Survey, Bruni (2020) has noticed that income per capita had increased rapidly in many countries during 1946–1990 but happiness had stayed constant or had increased insignificantly. Some controversial results have emerged from the research that was conducted across 132 nations by Oishi and Diener (2014). The authors revealed that life satisfaction was substantially higher in highly developed countries than in poor countries but a sense of the meaning in life was greater in poorly developed countries than in wealthy countries. According to Garcia-Alandete (2015) and Santos et al. (2012), meaning in life may enhance one’s life satisfaction and play an important role in achieving higher psychological well-being. If both life satisfaction and meaning in life can be identified, to some extent, as a source of one’s well-being, what should be the focus of a company seeking to increase well-being? Improved understanding of the impact of CSR on the links between company’s economic activity and well-being could help motivate companies to adopt a more responsible approach to business and, at the same time, avoid the mistakes that companies have made in the past. Since a private company, like any organization, is part of the society, its activities should be desirable, uncontroversial, as well as adhering to the norms, rules, traditions, and expectations of the society. Taking CSR ideas into account and recognizing that companies are fully responsible for their actions and the impact on the society, including economic, social, and environmental issues that are crucial for social welfare, companies’ economic activities should be analyzed in a broader context.

The aim of this paper is to conduct an analysis of the concept of well-being by exploring hedonic and eudaimonic approaches within the perspective of a more holistic outlook and identify theoretical links between company’s economic activity and human well-being from the perspective of CSR.

Tasks of the paper:

1) to analyze the concept of well-being within hedonic and eudaimonic approaches;

2) to identify theoretical links between company’s economic activity and human well-being from the perspective of CSR and provide a conceptual model.

Research methods: The term human well-being is not new in the scientific literature but scientists have not been able to reach a consensus in defining this phenomenon. In order to clarify the links between company’s economic activity and human well-being, firstly, the comparative analysis of scientific literature focusing on the meaning and multidimensionality of the term human well-being from the perspective of two main approaches – hedonic and eudaimonic – has been done. Following this, to identify the role of CSR and its impact on the links between company’s economic activity and human well-being, the analysis of empirical research has been conducted, exploring the manifestation of human well-being in two different contexts – a company following the principles of CSR, and one that is ignoring the same principles. Finally, summarizing the differences revealed by analyzing the relationship between company’s economic activity and the manifestation of human well-being in different contexts, the conceptual model of potential relations between company’s economic activity and human well-being, according to CSR, is provided.

The Origin of Well-Being and Theoretical Approaches

Over recent decades a lot of academic papers have been written seeking to define the conception of well-being and to explain the factors influencing its manifestation. It is important to notice that scientists analyze this phenomenon from different perspectives and in different contexts, with the result that we can encounter scholars’ opinions that partly, or completely, refute each other. Most scientists analyze well-being from two perspectives: the hedonic perspective and the eudaimonic perspective (Waterman, 1993; Ryan and Deci, 2001; Grant et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2012; Rothausen, 2013; Ryff and Keyes, 1995; Fisher, 2014; Lee and Kim, 2015; Garcia-Alandete, 2015). According to Ryff (2013), both approaches can be traced to the ancient Greek philosophy. The word hedonia is associated with a pleasant or enjoyable life, and eudaimonia is associated with a morally good or purposeful life (Rothausen, 2013). Hedonism theory emphasizes personal pleasure and comfort as the guiding principles in one’s life (Joshanloo, 2021). Hedonism was also divided into physical and spiritual pleasure in ancient times and it was approached from an individual, rather than a collective, point of view (Choi and Jang, 2017). So, the hedonic approach is focused on a short-term perspective at a personal level, while the eudaimonic approach is focused on a long-term perspective at a social level and, therefore, the defining of well-being becomes complicated and the content of a definition of well-being can vary widely.

Summarizing the opinions of different scientists, Garcia-Alandete (2015) states that, according to hedonic approach, pleasure is the greatest goodness, which brings the greatest happiness to the individual and is currently associated with ‘subjective well-being.’ From this perspective, well-being can be achieved if people’s lifestyle and behavior provide subjective enjoyment and pleasure (Steger and Samman, 2012). The hedonic approach focuses mainly on the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain and, therefore, it is more closely related to happiness (Ryan and Deci, 2001). The balance of positive and negative thoughts and feelings in individuals’ judgments is an important element in the hedonic approach to explaining subjective well-being (Grant et al., 2007). Even though subjective well-being encompasses more than positive feelings, which help people to feel happier, some authors comment on the use of the terms subjective well-being and happiness as though they were synonymous (Tov and Diener, 2013; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Kunzmann et al., 2000). Ryan and Deci (2001) have concluded that not all the desires that a person might value are valuable for promoting wellness for society and, as a consequence, they argue that subjective happiness cannot be equated with well-being.

Stiglitz et al. (2009) represent a similar position to the hedonism theory, stating that subjective well-being provides important information about the quality of life because it encompasses different aspects like cognitive evaluations of one’s life, positive emotions such as joy and pride, and negative emotions such as pain and worry. The authors have distinguished subjective well-being as one of the three main conceptual approaches, alongside capabilities and the welfare of economics as understood according to the theory of fair allocations, as suitable tools for measuring the quality of life. On one hand, all these approaches are closely interrelated, encompassing many dimensions, and they can reflect the quality of life comprehensively. On the other hand, however, these approaches have significant differences and do not allow the concept of well-being to be refined and properly qualified. White (2010) describes well-being as a process, or even a set of processes, which takes a different shape across space and time and, therefore, the conceptualization of well-being is complicated and the definition of well-being often remains at an intuitive level. Nevertheless, he suggests that distinguishing the three main dimensions of well-being as subjective, material, and relational, is a helpful contribution.

From the eudaimonic perspective, happiness is more associated with ‘psychological well-being’ and it incorporates self-determination, the achievement of goals, the meaning in life, the actualization of personal strengths, the fulfilment of existential goals, and the realization of human potential (Garcia-Alandete, 2015; Grant et al., 2007). Relying on Waterman et al. (2010), a strong identity commitment and a clear understanding of who people are, what their values are, and what they want to do in their lives, is essential for achieving well-being. The eudaimonic approach mainly focuses on meaning, self-realization, and the interpretation of psychological well-being in terms of the degree to which a person is able to function fully. Contrary to hedonic theory, enjoyment and pleasure are not considered necessary for achieving well-being. From the eudaimonic perspective, it is more important to find meaning and purpose in life, developing healthy relationships, and gaining a sense of competence and mastery (Steger and Samman, 2012).

Brickman and Campbell (1971) adapted subjective well-being or happiness theory and developed the hedonic treadmill theory. This theory states that human happiness remains stationary or in a neutral state in spite of efforts to advance it. Though human beings have the tendency to continuously pursue happiness, from the hedonic treadmill viewpoint, any new circumstances, such as the good or bad events people experience, only temporarily cause them to become happier or sadder. Positive events inspire positive emotions, which, in turn, improve subjective well-being and conversely. But human beings rapidly adjust to new circumstances and the effect of any good or bad events on the level of happiness quickly diminishes or even disappears (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Despite the widespread acceptance of hedonic treadmill theory, the authors (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005) attempt to show that certain types of intentional activities, such as discrete actions or practices which require some degree of effort to enact them, can help to achieve sustainable changes in well-being and can mitigate the counteracting effects of adaptation.

The impact of hedonic and eudaimonic behavior on well-being was tested by Steger et al. (2008), and by McMahan and Estes (2011), in empirical studies. The results of both studies were similar. Steger et al. (2008) revealed that eudaimonic behavior had a consistently stronger relation to well-being than hedonic behavior. It is interesting to notice that, on a global level, hedonic behavior was inversely related to positive emotions such as feeling proud, excited, appreciated, enthusiastic, happy, or satisfied, and positively related to negative emotions such as feeling sluggish, afraid, sad, anxious, or angry. Moreover, only eudaimonic behavior positively impacted the same day’s sense of living a meaningful life and had a positive long-lasting impact on the sense of living a meaningful life being prolonged to the following day. The results of the study by McMahan and Estes (2011) confirmed that only eudaimonic activity had a significant positive effect on both general well-being and its separate dimensions such as living a meaningful life and both mental and physical vitality. These results raise questions about the validity of the hedonic theory of well-being.

Seeking to determine the relationship between subjective well-being and finding meaning in life, Santos et al. (2012) surveyed 969 students from different colleges in The Philippines. The study’s results revealed that a subject’s well-being, measured in terms of life satisfaction, is positively related to finding meaning in life. The study revealed some differences between the males and females surveyed. Compared to females, male respondents had slightly higher scores in relation to life satisfaction and finding meaning in life. On the other hand, compared to female respondents, males reported a significantly higher level of finding meaning in life and a significantly lower level of searching for meaning in life.

The insights of academic papers and the results of empirical research suggest that the interpretation of well-being using the eudaimonic approach is more closely related to the existential issues of humanity viewed from a long-term perspective and it is also more in tune with a contemporary understanding of the concept of well-being and, therefore, is more meaningful and acceptable when seeking to further define the concept of human well-being.

The Efforts of Scholars to Define Human Well-Being

Dodge et al. (2012) acknowledge that a satisfactory definition of well-being has not yet been achieved and that all attempts to define well-being and to provide a new definition are focused on the different dimensions and descriptions of well-being, rather than on its definition. Criticizing an overly-narrow approach in explaining this concept, the authors define well-being as an equilibrium between the psychological, social, and physical resources, on the one hand, and psychological, social and physical challenges, on the other. According to Grant et al. (2007) and Roy (2018), psychological/emotional well-being can be reflected in happiness, satisfaction, self-esteem or a sense of religious freedom; social well-being can be reflected in the quality and breadth of people’s relationships; and physical/material well-being can be reflected in health, and in physical and financial security. When people have more challenges than resources, or vice-versa, the normative state of balance is violated. Our state of well-being is always fluctuating and it is difficult to achieve a stable state. Demo and Pashoal (2016) do not provide a definition of well-being but they state that, generally, well-being refers to subjective well-being, which is associated with pleasurable experiences, whereas psychological well-being is associated with human potential and fulfilment. Loveridge et al. (2020) distinguish objective, subjective and relational well-being, while recognizing that the conceptualization of this phenomenon still remains unclear and needs wider discussion.

Breslow et al. (2016) define human well-being “as a state of being with others and the environment, which arises when human needs are met, when individuals and communities can act meaningfully to pursue their goals, and when individuals and communities enjoy a satisfactory quality of life.” The authors use this definition in assessing human well-being in the context of the ecosystem and, like other authors mentioned above, they emphasize the dynamics of human well-being in a changing environment. According to Ashton and Jones (2013), “human well-being is the recognition that everyone around the world, regardless of geography, age, culture, religion or political environment, aspires to live well.” This definition is meaningful but at the same time ambiguous and it takes us back to the origins of this phenomenon and requires clarification concerning what the expression “well” means today and what it may mean for the next generations.

Vella (2019) raises another problem in defining well-being by noticing that the term well-being is sometimes used interchangeably with the term welfare. According to the author, these two terms differ, and welfare is more associated with social domains such as health, housing, education, employment, security and others, while well-being is understood in a more individual and subjective manner, as life satisfaction and quality of life. Roy (2018) supports the idea that the terms ‘welfare’ and ‘wellbeing’ both mean good life but notices that welfare research is concentrated on the societal or macro level, while well-being research reflects the personal or micro-level. Briguglio (2019) takes a different position, stating that welfare, generated from economic activity, does not necessarily reflect social well-being so that the two cannot be used as synonyms. According to the author, it is only at the early stages of an increase in economic development that welfare and well-being increase simultaneously. At the later stages of economic development welfare and well-being mean different things. This may happen because people’s expectations are different in developing and in developed countries and, therefore, it is not correct to use the terms well-being and welfare interchangeably and to define them in the same way. Besides the term ‘wellbeing’, Quiros-Romero and Reinsdorf (2020) use the term ‘economic welfare,’ which is a narrower concept than well-being, and can be reflected in current and lifetime consumption and other resources such as income, comprehensive wealth, and the time endowment of households that enables consumption. According to the authors, well-being can also be reflected in intangible aspects, which cannot be traded in a market, such as happiness, health outcomes, personal security, trust, bio-diversity, and others. The authors recognize differences between the concepts of ‘well-being’ and ‘economic welfare,’ and they even use the term ‘social welfare,’ but the distinction between ‘welfare’ and ‘economic welfare’ still remains unclear.

Summarizing the efforts of scientists to define the term well-being, it is obvious that well-being, like many other social phenomena, is a multidimensional, dynamic process, which is influenced by many subjective and objective forces at both macro and micro levels and, therefore, scientists have not been able to reach a consensus in defining this phenomenon. Despite the different authors’ views on defining this concept, human well-being can be defined as continuous human state that enables a person to enjoy his or her life and pursue long-term goals by living a meaningful life in harmony with other people, society, and nature. However, it can be argued that in analyzing this phenomenon and its relationships with other phenomena, including CSR, special attention should be paid to keeping a proper balance between the aspects on which the hedonic approach focuses and the aspects that the eudaimonic approach emphasizes.

The Links Between Company’s Economic Activity and Human Well-Being

For a long time, a company was considered socially responsible if it was associated with philanthropic activity, and a company’s support for the community and for nonprofit projects was seen as the main sign of its responsibility. According to such traditional views of economics, the more companies donated for society’s needs, the more societal well-being might be achieved. As a result, it seemed that the links between CSR and human well-being were obvious and did not require deeper academic investigation. This position is somewhat superficial, however, and sometimes it is even incorrect, for the following, closely-interrelated reasons.

First, such an approach to CSR is too narrow, does not reflect CSR ideas, and does not meet increasing requirements for CSR. From a holistic point of view, CSR encompasses the business strategies and the tools that companies apply in their business activity to earn a profit, and not only in their purely charitable activity. The European Commission (2011) emphasizes that CSR “concerns actions by companies over and above their legal obligations towards society and the environment.” It means that companies are responsible for both their negative and their positive impact on society, or, in other words, for both the problems that a business creates and the good decisions that a business is able to make. Socially responsible companies should create and maximize their positive impact on all stakeholders, and on society at large, as well as identifying, preventing, mitigating or eliminating their adverse impact.

Second, CSR is a very dynamic and multidimensional phenomenon, which requires the consistent attention and analysis of the companies’ managers. Not all CSR tools are equally helpful in achieving the best results or for creating value for a company and for society, because companies operate in relation to particular markets and under certain conditions. The activity of every business is specific and, therefore, only an appropriate CSR strategy can increase a company’s reputation and value and create vital competitive advantages for a company in a long term. According to Porter and Kramer (2006), no one company is able, and obliged, to solve all the problems of society, but every company can, and must, identify those social issues that are related to the company’s activity and that can be used to create competitive advantages and to ensure business success. Gyves and O’Higgins (2008) highlight another important feature of CSR. According to these authors, if CSR is originally adopted because of external coercion, without being incorporated into the strategy and value system of a company, it does not help to create any internal benefit for a company or any external benefit for society, with the result that its contribution to well-being is negligible and temporary.

Third, companies operate under market conditions and must meet the requirements of the shareholders to work profitably. As a result, companies must look for the most effective ways to reflect the expectations of all the stakeholders, including the government, employees, customers, community, and others, and it must also achieve those companies’ goals, while remaining competitive and profitable. In many cases, CSR requires not only a good strategy but a huge investment, also, especially if companies decide to implement the new green technologies or other environmental projects as part of their activity. A company must not lose its position in the market as a result of the implementation of CSR and implementation must be done in such way that profitability is maintained, competitive advantage is enhanced and the quality of living standards for society is increased.

Businesses introduce all kinds of products and services to the economy, the demand for which increases as the population grows and their income increase. In order to satisfy the constantly growing consumption and remain competitive in the market, businesses often ignore CSR. Lack of awareness on the part of businesses and consumers increases irresponsible production and consumption, which leads to unsustainable economic development and can be more harmful than beneficial in a long-term projection. To produce more products, corporates need more natural resources. In the early 1970s, the planet went into global overshoot (Schneider Electric & Global Footprint Network, 2019). It means that since this decade, humanity’s demand for nature has exceeded its capabilities and humanity every year used more from nature than the planet’s ecosystems are able to regenerate in the entire year. According to the data provided by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2011), the food sector accounts for around 30 percent of the world’s total energy consumption, while 1.3 billion tonnes of food produced globally is wasted or lost each year. Close to 20 percent of the world population is lacking food, while more than 50 percent of the population in 34 out of 36 OECD countries is overweight, and almost 25 percent of the population is obese (OECD, 2019).

Globalization and high competition in the market require business companies to operate efficiently, reducing production costs as much as possible. Since business does not always ensure the high quality of its products, either in terms of contributing to a clean and safe environment, or in establishing a healthy ‘microclimate’ within corporates. It is now widely recognized that business is responsible for many pollution problems worldwide, leading to the deaths of millions of people. In 2015, diseases caused by pollution were responsible for about 16 percent of all premature deaths worldwide (Landrigan et al., 2018). Though this problem occurs mostly in low-income and middle-income countries, due to lack of clean water and sanitation, the developed industrial countries suffer more and more from airborne fine particulate pollution, tropospheric ozone pollution, occupational chemical pollution, and soil pollution by heavy metals and chemicals (including lead) (Landrigan et al., 2018). Brymer et al. (2019) state that human well-being cannot exist without nature’s well-being. Therefore, appropriate attention of governments and policymakers across the world is needed in order to preserve the harmony between people and nature.

GDP reflects the economic growth or output of the economy. From an hedonic approach, the more business produces goods and provides services, the more it contributes to creating well-being, because customers can consume more and experience higher physical pleasure. But not every company’s activity meets society’s needs and ensures sustainability. Mostly, it is only the activity of responsible companies that will be able to satisfy society’s expectations and to avail of the opportunity to achieve higher living standards. So, from an eudaimonic view, economic growth, measured by standard quantitative indicators alone, reflects economic welfare or economic prosperity rather than increased well-being. Such growth allows more money to be allocated to society but does not address the causes of existing problems, or eliminate undesirable consequences. The results of a comparative study conducted by Weenhoven (2000) in 40 countries around the world during the period of 1980–1990 confirm this statement. The author has revealed that welfare, as measured by social security expenditure, is not statistically related to well-being, measured in terms of the degree to which people lead a healthy and happy life. On other hand, the higher the income inequality of a country, the lower will be its achievement in terms of well-being and happiness (Okulicz-Kozaryn and Mazelis, 2017). In order to provide a more complete and precise picture of human well-being, subjective indicators should be used alongside economic indicators.

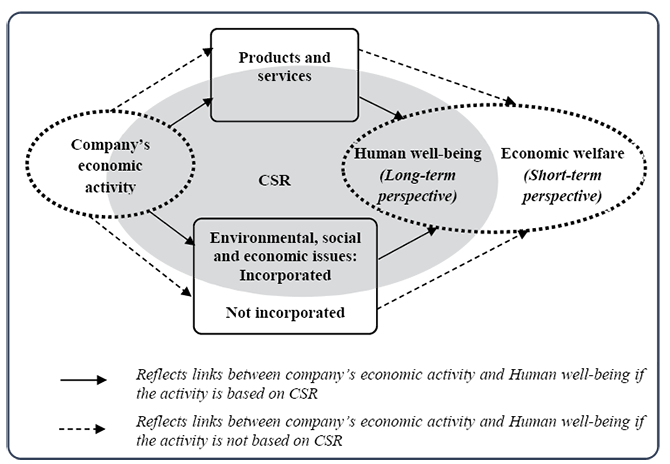

When company’s economic activity is based on CSR principles and environmental, social, as well as economic issues are taken into account in producing goods and providing services, this contributes to increasing human well-being. This influence is particularly significant in the long term. The more responsibly companies operate in their markets, and the higher the CSR requirements they assume, the more significantly they will contribute to well-being. And, in the same way, if business activity is focused solely on economic results and ignores CSR, such activity increases economic welfare but the contribution to well-being can be minimal or in some cases even negative. This model does not seek to deny the correlation between human well-being and economic welfare but, rather, notices that economic welfare relies more on material prosperity, which does not always reflect the intangible values of being happy, safe, satisfied and living a meaningful life. To have more does not always mean to live better, and, as a result, moving from a focus on quantity and thinking only about today, to a focus on quality and long-term values, could be useful for all. If CSR is ignored, having ‘more’ today in most cases means encountering more social and ecological problems and concerns for everybody – business, society, and generally for the whole humanity. The less responsible the activity of companies becomes, the less economic welfare, economic prosperity and well-being will have in common and the links between these three dimensions will be weaker. The figure below represents differences in links between company’s economic activity and human well-being from the perspective of CSR.

Figure 1.

Model of the theoretical links between company’s economic activity and human well-being according to CSR

Source: composed by author.

The model illustrated above in Figure 1 combines eudaimonic and hedonic approaches. CSR refers to responsible behavior of companies to pursue well-being of society in the long term, while rejecting short-term gains that can undermine sustainable economic growth. Using an eudaimonic approach, human well-being also focuses on the long-term pursuit of meaningful life and life satisfaction. A positive relation between life satisfaction and a meaningful life was also found in an empirical study conducted by Santos (2012). This suggest that an eudaimonic approach is meaningful in defining the links between companies’ economic activities based on CSR and well-being, while the hedonistic approach is more appropriate for defining the links between companies’ economic activities and economic welfare when CSR is ignored. The model is consistent with the results of the research conducted by Joshanloo (2021), in which he revealed that life satisfaction and hedonic values such as pleasure, and having an exciting and comfortable life, are not longitudinally linked. He has also found that hedonic values declined over time, while life satisfaction remained largely stable. The research was conducted using data from the survey of 7199 Dutch individuals above the age of 15 years, collected during the 13 years from 2008 to 2020 by Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for Social Sciences. Research conducted by Jia et al. (2021) demonstrates similar results among Chinese junior high school students. The authors found that hedonic values are not related to life satisfaction while eudaimonic motivation positively influences life satisfaction.

Many researchers have investigated the links between CSR and human well-being and in most cases a positive relationship has been found. If CSR is incorporated into the value system of a company, if it becomes the strategic part of a company, and if it is implemented on a voluntary basis, then CSR becomes, not only a strong competitive advantage, helping a company to earn a profit, but it also contributes to the well-being of society (Gyves and O’Higgins, 2008). Macassa et al. (2020) reviewed sixteen studies conducted in different European countries and published between 2007 and 2019, investigating the relationship between CSR and different dimensions of well-being. They came to the conclusion that the majority of identified studies have found that CSR positively impacted employee job satisfaction, work conditions, work–life balance and empowerment. According to Carpion and Avramchuk (2017), employee well-being should identify their health as one of the many CSR elements. Therefore, in order to achieve higher subjective well-being for employees, the authors propose that corporates include healthy workplace initiatives for their employees into CSR programs. Such CSR programs might increase the corporate reputation and decrease corporate healthcare-related costs because employees with higher subjective well-being have significantly lower health-related costs compared with employees experiencing lower well-being.

Combining the Gallup World Poll survey that represents about 98 percent of the world’s population and Sustainable Development Index data, Neve and Sachs (2020) revealed a highly significant correlation (r = 0.79) between sustainable development and subjective human well-being. It is interesting that increased sustainable development has a very small influence on subjective well-being in less economically developed countries while the role of sustainable development is very important in highly developed countries. Generally, less developed countries are concentrated on economic results rather than on sustainable development, and economic achievements provide higher positive emotions. As countries become richer, human well-being can be increased only by sustainable economic growth. This provision can be confirmed by the similar results revealed in the empirical research presented in Veronese et al. (2017). The authors found that for the Israeli Arabs and Palestinians from the West Bank/Gaza Strip, where poverty and a high level of unemployment is widespread, economic security (i.e. level and stability of income, satisfying the main material needs) is more important for positive experience and optimism than social functioning or spirituality. Wealthier countries are likely to have better standards of living and people do not need to worry about basic material needs. However, Swift et al. (2014) revealed that the gap in well-being between poorer and wealthier countries is larger among older people also. So, when investigating the links between CSR and human well-being, the national context needs to be considered as well.

Business and society should maintain close relations and cooperation to achieve the best results for both. Business is able to attract and encourage a society towards responsible consumption using new patterns of responsible business activity. Hohnen and Potts (2007) even use the term ‘responsible consumerism,’ which is more about the real relationship between producers and consumers than exclusively the changes of consumers’ preferences to consume or not consume certain goods or services. Mutual understanding and efforts to achieve the same goals have a key role to play in creating long-term sustainability and well-being in all areas of our life.

Conclusions

A lot of academic papers and empirical studies had been done by scientists over the world over recent decades investigating the concepts of CSR and well-being but there is still a lack of research conducted seeking to define both concepts and clarify the links between these two phenomena. Both concepts have deep origins, are multidimensional, dynamic, and complex, and can be defined at different levels, and, as a result, widely different interpretations of these phenomena are possible and this can lead to controversial results. Both CSR and human well-being are formed at the micro level, although they are influenced by both micro and macro factors. In this article, the links between company’s activity, CSR and human well-being are analyzed at the micro level, but the identified relationship among these phenomena may lead to certain conclusions at the societal level as well.

Summarizing the analysis performed in this study, it is worth noting that two approaches are often used by scholars seeking to explain and determine the concept of well-being. Both approaches are traceable to the ancient Greek philosophy and explain well-being from either a hedonic or an eudaimonic perspective. The hedonic approach is focused on a short-term perspective and emphasizes pleasure as the greatest good, because it helps people to feel happier. A different position is taken by the eudaimonic approach, which is focused on a long-term perspective and is more associated with self-realization, the fulfilment of existential goals, self-determination and the achievement of a meaningful life. The insights of academic papers and the results of empirical research suggest that the interpretation of well-being using the eudaimonic approach is more closely related to the existential issues of humanity viewed from a long-term perspective, making this approach more suitable to our contemporary understanding of the concept of well-being. Therefore, human well-being can be defined as a continuous human state that enables a person to enjoy his or her life and pursue long-term goals by living a meaningful life in harmony with other people, society, and nature.

The interpretation of CSR from a holistic point of view, where CSR is understood as a business strategy and one of the tools that companies apply to their activities to maximize their positive impact on all stakeholders and society at large, while, at the same time, identifying, preventing, mitigating or eliminating their adverse impact and earning a profit, and this requires an elaborated analysis linking CSR with company’s economic activity and human well-being. Business that ignores the ideas of CSR helps to increase economic welfare rather than increasing well-being. Irresponsible production and consumption lead to unsustainable development and can be more harmful than beneficial in the long term. Responsible companies’ activities that address the relevant environmental, social, and economic challenges in producing goods and providing services unequivocally contribute positively to human well-being in the long term. CSR contributes to society by enabling companies to satisfy the expectations of the society in which they operate and by enabling them to exploit every opportunity to achieve higher living standards and more sustainable development.

References

Ashton, K., & Jones, C. (2013). Geographies of Human Wellbeing. Geography Teachers’ Association of Victoria Inc. https://www.gtav.asn.au/documents/item/40

Breslow, S. J., Sojka, B., Barnea, R., Basurto, X., Carothers, C. et at. (2016). Conceptualizing and operationalizing human wellbeing for ecosystem assessment and management. Environmental

Science & Policy, 66, 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.023

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Eds.), Adaptation-level theory (pp. 287–305). New York: Academic Press.

Briguglio, M. (2019). Wellbeing: An Economics Perspective. In Vella, S., Falzon, R., Azzopardi, A. (Eds.), Perspectives on Wellbeing: A Reader (pp. 145-157). Brill Sense, Boston. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004394179_012

Bruni, L. (2020). Economics, wellbeing and happiness: a historical perspective. In D. Maddison, K. Rehdanz, & H. Welsch. (Eds.), Handbook on Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment (pp. 13–24). Economics 2020. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788119344

Brymer, E., Freeman, E., & Richardson, M. (2019). Editorial: One Health: The Well-being Impacts of Human-Nature Relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01611

Carpion, R. A., & Avramchuk, A. S. (2017). The Conceptual Relationship between Workplace Well-Being, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Healthcare Costs. International Management Review, 13(2), 24–31.

Choi, Y. Ch., & Jang, J. H. (2017). Analysis of the Causal Relationships Among Factors Affecting Community Well-Being for Living Based on systems Thinking: The Cases of Korean Local Communities. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 16(3), 1–16. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/Analysis-of-the-causal-relationships-among-factors-affecting-community-1939-6104-16-3-120.pdf

Demo, G., & Paschoal, T. (2016). Well-Being at Work Scale: Exploratory and confirmatory validation in the USA. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 26(63), 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272663201605

Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

European Commission (2011, October 25). A Renewed EU Strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/com/com_com(2011)0681_/com_com(2011)0681_en.pdf

Fisher, C. D. (2014). Conceptualizing and Measuring Wellbeing at Work. In P. Y. Chen, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Work and Wellbeing, (pp. 9–33). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell018

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2011). “Energy-Smart” Food for People and Climate: Issue Paper. https://www.fao.org/3/i2454e/i2454e.pdf

Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. New York Times, p. 17.

Garcia-Alandete, J. (2015). Does Meaning in Life Predict Psychological Well-Being? An Analysis Using the Spanish Versions of the Purpose-In-Life Test and the Ryff’s Scales. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 3(2), 89–98, https://doi.org/10.5964/ejcop.v3i2.27

Grant, A. M., Christianson, M. K., & Price, R. H. (2007). Happiness, health, or relationships: Managerial practices and employee wellbeing tradeoffs. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(3), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2007.26421238

Gyves, S., & O’Higgins, E. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: an avenue for sustainable benefit for society and the firm? Society and Business Review. 3(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465680810907297

Hohnen, P., & Potts, J. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility: An Implementation Guide for Business. International Institute for Sustainable Development. http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2007/csr_guide.pdf

Jia, N., Li, W., Zhang, L., & Kong, F. (2021). Beneficial effects of hedonic and eudaimonic motivations on subjective well-being in adolescents: a two-wave cross-lagged analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1913641

Joshanloo, M. (2021). There is no temporal relationship between hedonic values and life satisfaction: A longitudinal study spanning 13 years. Journal of Research in Personality, 93(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104125

Kim, H. L, Woo, E., Uysal, M., & Kwon, N. (2018). The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1584–1600, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2016-0166

Kunzmann, U., Little, T. D., & Smith, J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 15(3), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.15.3.511

Landrigan, P., Fuller, R., Acosta, N. et al. (2018). The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. 391(10119), 462–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32345-0

Lee S. J., & Kim Y. (2015) Searching for the Meaning of Community Well-Being. In: S. Lee, Y. Kim, & R. Phillips (Eds.), Community Well-Being and Community Development (pp. 9–23). Springer Briefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12421-6_2

Levitt, T. (1958). The Dangers of Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review 36(5), 41–50.

Loveridge, R., Sallu, S. M., Pesha, I. J., & Marshall, A. R. (2020). Measuring human wellbeing: A protocol for selecting local indicators. Environmental Science and Policy, 114, 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.09.002

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

Macassa, G., McGrath, C., Tomaselli, G. & Buttigief, S. C. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being in Europe: a systematic descriptive review. Health Promotion International, 36(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa071

McMahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2011). Hedonic versus Eudaimonic Conceptions of Well-Being: Evidence of Differential Associations with Self-Reported Well-Being. Social Indicators Research, 103(1), 93–108. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9698-0

Neve, J. E., & Sachs, J. D. (2020). The SDGs and Human Well-Being: a Global Analysis of Synergies, Trade-offs, and Regional Differences. Scientific Report, 10, 15113. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71916-9

Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2014). Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychological Science, 25(2), 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613507286

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., & Mazelis, J. M. (2017). More Unequal in Income, More Unequal in Wellbeing. Social Indicators Research. 132, 953–975.

Oluyemi, J. A., Yinusa, M. A., Abdulateef, R., & Akindele, I. (2016). Corporate Social Responsibility and Workers’ Well-being in Nigerian Banks. African Sociological Review, 20(2), 89–101. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/asr/issue/view/15605

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2019). The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Quiros-Romero, G. & Reinsdorf, M. (2020). Measuring Economic Welfare: What and How? International Monetary Fund. Policy Paper, 2020 (028). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513544588.007

Rothausen, T. J. (2013). Hedonic and Eudaimonic Job-Related Well-Being: Enjoyment of Job and Fulfillment of Job Purpose. Working Paper. University of St. Thomas, Minnesota. https://researchonline.stthomas.edu/esploro/outputs/991015130931503691

Roy, A. (2018). The idea of social well-being and its utility in geographical research. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 5(7), 1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1729/Journal.19246

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D. (2013). Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Special Article, https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727.

Santos, M. C. J., Magramo, C., Oguan, F., Paat, J. J., & Barnachea, E. A. (2012). Meaning in Life and Subjective Well-being: Is a Satisfying Life Meaningful? International Refereed Research Journal, 3(4), 32–40.

Schneider Electric & Global Footprint Network. (2019, July). The Business Case for One-Planet Prosperity. 2nd edition. https://www.se.com/ww/en/download/document/one_planet_prosperity/?ssr=true

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004

Steger, M. F., & Samman, E. (2012). Assessing meaning in life on an international scale: Psychometric evidence for the meaning in life questionnaire-short form among Chilean households. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 182–195. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i.i3.2

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/finances/presse/dossiers_de_presse/090914mesure_perf_eco_progres_social/synthese_ang.pdf

Swift, H. J., Vauclair, C. M., Abrams, D., Bratt, C., Marques, S., & Lima, M. L. (2014). Revisiting the Paradox of Well-being: The Importance of National Context. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(6), 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu011

Thomas, J. (2009 April). Working Paper: Current Measures and the Challenges of Measuring Children’s Wellbeing. Newport: ONS.

Tov, W., & Diener, E. (2013). Subjective Well-being. Research Collection School of Social Sciences. Paper 1395. http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/1395

Vella, S. (2019). Wellbeing: A Welfare Perspective. In S. Vella, R. Falzon, & A. Azzopardi (Eds.), Perspectives on Wellbeing: A Reader. Brill Sense, Boston, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004394179

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Dagdouke, J., Addimando, L., & Yagi, S. (2017). Measuring Well-Being in Israel and Palestine: The Subjective Well-Being Assessment Scale. Psychological Reports, 120(6), 160–1177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117715479

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., & Williams, M. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903435208

Weenhoven, R. (2000). Wellbeing in the Welfare State: Level not higher, distribution not more equitable. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 2, 91–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010058615425

White, C. (2010). Analysing Wellbeing: A Framework for Development Policy and Practice. Development in Practice, 20(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903564199