Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2023, vol. 13, pp. 6–21 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2023.13.11

The Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”

Dovilė Lisauskienė

Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Lithuania

Dovile.lisauskiene@vilniustech.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0474-4747

Vilmantė Aleksienė

Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, Lithuania

vilmante.aleksiene@lmt.lt

Abstract. The Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” is the result of the research using constructivist grounded theory strategy. The socio-educational factors of recreational activities carried out in regional open youth centres/spaces were investigated. The study has included young people with fewer opportunities (YPFO) aged 16–20 and the youth workers. The study started in January and ended on September 2021.

In the research data analysis, the recurring word “invisible” was noted, bringing up the image of the “invisible hand”. The metaphor of the “invisible hand” was used to visualize, understand and explain the process of social education through recreation. The constructed grounded theory – the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”, was linked to the economical theory of the Invisible Hand described by the economist A. Smith (1776).

It has been revealed that it is a process consisting of visible and invisible sub-processes running simultaneously. The invisible one is not direct or pre-planned. It is a process that can be accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful.

Keywords: socio-education, young people with fewer opportunities, social work, open youth centre, the Invisible Hand theory, constructivist grounded theory.

Recieved: 16/05/2023. Accepted: 06/09/2023

Copyright © 2023 Dovilė Lisauskienė, Vilmantė Aleksienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

As global social, economic, and demographic trends change, so does the attitude towards young people with fewer opportunities and their education. Due to structured environment, formal education is not able to meet the needs of modern society, therefore, more and more attention is paid to informal learning (EU Youth Strategy 2019-2027; Garbauskaitė-Jakimovska, 2014). In this paper, informal learning is related to leisure activities (Surg, 2014) and leisure activities to the broader concept of recreation (Zarotis & Tokarski, 2020; McLean et al., 2015; McLean et al., 2005), which encompasses the elements of the process of personal engagement, advocacy, shared responsibility, and the process of building societal well-being (Hurd et al., 2021; Crompton, 2008). Socioeducation through recreation is associated with the dimension of self-directed learning, given that it is not always a conscious process and is often related with implicit learning and tacit knowledge (Belhassen, 2021; Hollingworth, 2012).

Recreation can be analysed from different perspectives, considering it as work (Hurd et al., 2021), activity (Belhassen, 2021; Torkildsen, 2012), entertainment (Isik, 2018), pleasure and enjoyment (Surg, 2014), wellness (Nagata et al., 2020), learning and socialization (Stebbins, 2018, 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Kleiber et al., 2011; Sivan, 2008; Crompton, 2008; McGuire & Mcdonnell, 2008) and other. Research has found that for YPFO, involvement and participation in leisure activities provide an opportunity to re-engage with society (Glover, 2015; Sivan, 2008; Hutchinson & Kleiber, 2005), so it is important to understand this process as comprehensively as possible.

Socioeducation through recreation can be studied to reveal a holistic process, i.e. it is analyzed by highlighting the conditions for the process to start, naming the factors that promote and hinder the description of the entire course of the process, and emphasizing other sequentially occurring processes. Therefore, research is needed that would reveal the consistent progress of the process of social education through recreation. The experience of YPFO can be useful for other participants in the process of social education through recreation. Their experience participating in recreational activities and visible significant socio-educational results would allow others to grow and improve. YPFO are socially one of the most vulnerable groups, but their positive integration into society is one of the highest priorities. The aim is not to help youth, but to enable them to make decisions to develop and improve themselves. A free, unrestricted, and safe environment with no obligations is one of the most suitable for realizing this vision. Nevertheless, YPFO are available in their environment, where they feel they belong. Thus, initiating change through an informal (leisure) environment, conversations, games, and other activities is one of the best tools to help create an understanding of the process of social education through recreation. Currently, there is a lack of research that would prove the significance and meaning of this process and reveal the process itself. The main research problem is raised of how the process of social education of young people with fewer opportunities takes place through recreation.

The object of the research is the social education of young people with fewer oportunities through recreation.

The aim of the research is to construct the grounded theory of recreation about the socio-education of young people with fewer opportunities through recreation, revealing the experiences of participation in recreational activities.

The novelty of the research is revealed by the extension of the concept of recreation to the field of socio-education. The work discusses the whole process of socio-education, highlighting the formalised-visible and informalised-invisible sub-processes, for the understanding and explanation of which the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” linked to the Invisible Hand theory described by the economist Smith (1776, cited in 2004) is constructed.

Research Sample and Participants

The study has included young people with fewer opportunities aged 16-20, who have been the visitors of open youth centres and spaces or the participants in recreational activities and residents in the region reached out by a mobile youth worker. People working with youth were also chosen for the study.

The duration of all interviews with young people with fewer opportunities in the region is 6 hours and 39 minutes. 13 in-depth interviews involving 11 young people with fewer opportunities have been conducted.

The duration of all interviews with youth workers is 6 hours and 42 min. 7 in-depth interviews have been conducted with 7 persons working with youth. The total duration of in-depth interviews is 13 hours and 21 min.

Methods of the Research

Constructivist grounded theory (hereinafter - CGT) is an inductive and abductive research strategy, where collected empirical data are coded, constantly compared, then abstracted, and transferred to the theoretical level of coding. At this point, it is noted that the inductive and abductive strategies are combined, since all the studied data are theoretically verified and interpreted until the most reliable theoretical interpretation of the data is reached and a new underlying theory is constructed (Bryant & Charmaz, 2019; Hense & McFerran, 2016).

In the construction of a grounded theory of socio-education through recreation for young people with fewer opportunities, sensitising concepts were first put forward. As Charmaz (2006) argues these are key ideas that help to frame the research problems. After the first interview was transcribed, the initial coding of the data began. The data were then compared with the new data received throughout. Focused coding involved combining the codes into categories, comparing them, trying to raise new questions, and filling in the features of the categories. New participants were recruited from the theoretical sampling process based on the emerging data. In the presence of category saturation, theoretical coding was used to search for relationships between categories and to develop theoretical concepts – core categories – and to construct a new GT theory.

The memos were written in two forms: loose memos at the beginning of the study and analytical memos with graphical visualizations during the data analysis. In the analytical process, memos are one of the aspects of theory construction since theoretical categories are developed and data are grouped (Williams & Keady, 2012; Charmaz, 2006). The researcher’s graphical memos reflect the relationships between subcategories and describe the properties of the categories. The researcher used the constant comparison method to combine the subcategories into thematic categories, which highlighted the essential categories referred to as the power held by the youth worker and the implicit socio-educational purpose in recreational activities. As Charmaz & Thornberg (2021) argue, the analysis of the substantive categories with the research participants was associated with the development of new lines of inquiry, thus, the substantive categories were related to theoretical concepts and the metaphor of the “invisible hand”.

Before beginning to write the theory, it is important to emphasize another key element of a constructivist grounded theory called theoretical saturation, which is not simply the emergence of repetitive data, but the conceptualization of data comparison. To ascertain whether categories are saturated, the researcher drew on the recommendations of Charmaz (2014), and asked the following questions: What data were compared within and between categories? What do I think about these comparisons? Where are they leading me? How do the comparisons reveal theoretical categories? What other directions, if any, can the comparison lead to? What new conceptual connections, if any, can be observed? The sense of theoretical saturation allowed us to start writing theory.

By linking the new Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” concept, the scientific literature was analyzed and key theoretical links emerged. The discussion with the economist allowed the theoretical relevance of the theory to be verified and highlighted, while the discussion with the participants in the study – individuals working with young people – highlighted the practical relevance of the theory, the understanding of the process of socio-education in an informal (recreational) setting, and the usefulness and the need for recreational activities. The Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” constructed during the research reveals the precondition for the socio-educational beginning, the internal and external factors determining the process, and the socio-educational process itself.

Analysis of the Research Results

A change in psycho-emotional state is a prerequisite for socio-education to begin. It is like a spiralling upwards process, one element replacing and completing the previous one.

Young people with fewer opportunities engage in activities spontaneously for personal gain. Social environmental factors reinforce and sustain the process, motivating them to keep going and to continue. Thus, engagement and participation in leisure activities lead to a transformation: emotional and physical discharge. A friendly and supportive atmosphere helps young people with fewer opportunities to ‘heal’, leading to less emotional tension and relaxation. The feeling of being cared for makes the young person feel less lonely, and it reduces the heavy feelings of anger and sadness by increasing happiness and joy. The trust of others gives a sense of self-confidence and therefore a sense of recovery and relaxation. Recovery promotes openness, trust, acceptance of knowledge and other information. The knowledge gained and the new more positive experiences become a “recharge”. Knowledge implies a personal desire to improve.

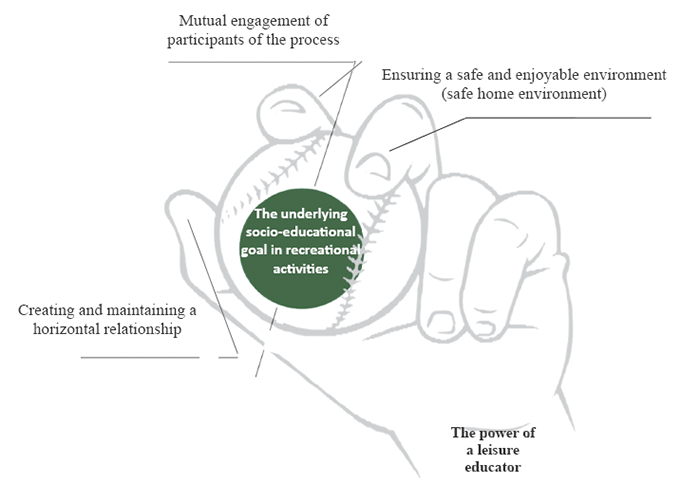

Figure 1

“Invisible hand” in the process of social education through recreation (compiled by the authors).

The metaphor of the “Invisible hand” helps to visualize the process of social education through recreation (see Figure 1). It is the invisibility of the processes taking place behind the obvious formalized facts that often emerges in data analysis. For instance, the target group at the initial stage often chooses passive strategies in participating in recreational activities as if it is invisible; creative activities manifest themselves as self-realization which is not directly expressed; or the invisible side of the role of a leisure educator emerges through the invisibility of socio-educational meanings while organizing pleasure-based recreational activities. Thus, the principle of invisibility when young people feel free and unlimited by formal educational activities and aspirations helps to ensure the informal socio-educational process and preserves the existence of the pursued socio-educational goals. All this is determined by the following aspects: 1) the characteristics of the target group, such as unmotivated and inactive young people who do not have the same conditions as their peers and 2) the specificity of open work with young people when the “low threshold” principle is followed and the services provided meet the needs of young people, i.e. services are available to young people in their spare time; they are close to home, free of charge and guarantee confidentiality and freedom.

The invisible socio-educational power, revealed in the study through the expression of formal and informal professional functions and personal characteristics of the youth worker, is analysed in the grounded theory as a social construct that ensures the progress of the socio-educational process and presupposes the emerging concept of the leisure educator. The realization of socio-educational power using the “invisible hand” metaphor is associated with the management strategy of the socio-educational process which is the main axis of the grounded theory.

The informal part of social education is also invisible. This invisible sub-process of socio-education is formed by three main factors: the impact of the informal leisure environment (social-inclusive, recreational-educational, educational-preventive, psychological), creating and maintaining a horizontal relationship and the involvement of the participants in the mutual process and a share of perceived responsibility. The increasing effectiveness of the results of the socio-educational process is determined by an invisible force, which is the maintained balance of responsibility among the actors participating in the process (YPFO and a leisure educator).

Directing the process of socio-education is compared to the operation of the “invisible hand” that is characterized by accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful movements.

The complexity of ensuring the participation of young people in recreational activities in the YPFO is evident when analysing data from the interviews with YPFO showed that youth workers. This highlights the accidental movements, when it is only after meeting the young person that it is known whether or not they will participate in the activity.

Efforts to improve recreational activities reveal elements of conscious. The youth worker consciously seeks ways, methods, means to organise and implement exciting new leisure activities. External factors – the encouragement of another, the social contact available, the nature of the recreational activity – reveal purposeful or situational learning in a social context. Inviting another person to engage in the activity and deciding to participate in the activity allows the participant to learn from the other person by observing their behaviour and environmental factors. Youth workers try to change the attitudes of YPFO by setting an example and promoting awareness.

Spontaneity in engagement has been discussed in the previous subsections, but in the context of the dynamic nature of the socio-educational process, it is seen as a factor that determines the speed of variability of the process. In the opinion of the participants, recreational activities need to be continuously updated and innovative in order to be of interest YPFO.

Purposefulness refers to the planning of recreational activities in advance. Youth workers organise recreational activities for YPFO in a purposeful way: they conduct surveys on what young people would like to do, take time to plan the activities, search for information on the internet, write up projects, observe and evaluate young people during the activities, etc. This shows how the socio-education process works in a targeted way.

The dynamics of the socio-educational process (“invisible hand” movement directions and speed) are constantly influenced by the internal and external factors that determine the participation of YPFO in recreational activities.

Recreational activities as the opportunities held in the “invisible hand” of the leisure educator become fundamental and determine the impact of socio-education on the process and its result. Like throwing a ball at a target, the operation of the “invisible hand” in the context of socio-educational theory is directed at the YPFO motivation to get involved. Are they going to catch it? Will they catch it or not? Will they like it? Will they not like it? Will they enjoy it? Will they understand the meaning of it? Will they stay there? Or will they leave? It requires constant work and a successful result is expected only in the long term. Research data showed that YPFO need time to become acquainted with a new environment, adapt to it, understand it, feel it and become open. For a leisure educator, establishing contact and positive development of mutual relations also requires time, which indicates that the short-term effect of participating in recreational activities leads only to a change in the psycho-emotional state, and not to significant socio-educational results.

The analysis of the data from the interviews with YPFO showed that they feel more open, braver, and more confident in themselves and others after participating in recreational activities. This increases their self-esteem and the desire to improve appears. During the research, it became apparent that the process of changing the psycho-emotional state moves upwards like a spiral, one element changes and complements the previous one. Social environment factors strengthen and support the process; they motivate not to stop and continue the activity. Thus, after getting included and engaged, and participating in recreational activities, a transformation takes place from emotional and physical discharge, reduction of emotional tension, release of feelings (catharsis) towards positive feelings, relaxation and recovery, which promotes openness, trust and acquisition of knowledge and other information. Acquired knowledge and new, more positive experiences become a “recharge” of energy. Knowledge presupposes a person’s desire to improve. Meanwhile, the participation of a leisure educator in short-term recreational activities is a way to get to know young people, a method to establish contact and a means of overcoming personal negative experiences.

In general, it can be stated that Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” applied in open work with YPFO is based on the following factors: the main visible factors of the process such as inclusion and engagement, acting in participation, positive change in the inner state and achievement of socio-educational outcomes, and the invisible action that takes place behind the obvious formalized facts like throwing a ball at a target in the hope of engaging YPFO in recreational activities, encouraging participation and interest, maintaining their participation and initiating changes.

The strategy of managing the process, which is the main axis of the grounded theory, is considered a socio-educational power, i.e. the combination of formal and informal professional functions performed by a youth worker and the set of youth worker’s personal qualities such as professionalism, leadership and tolerance. It is the realization of the socio-educational power in the metaphor of hand that reveals the course of the process through hand movements that can be accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful. The direction of the socio-educational process, or the purposeful control of the hand, is determined not only by the youth worker and the YPFO, but also by internal and external factors including the effect of the informal leisure environment, the creation and maintenance of a horizontal relationship, the mutual engagement of the process participants. An invisible force is the share of responsibility between the participants, which helps maintain a balance between these movements.

Therefore, the entire socio-educational process is constructed by visible factors and the invisible operation of the socio-educational hand, in the new constructivist grounded Socio-educational Theory of “Invisible Hand” perceived as simultaneously occurring sub-processes of socio-education of YPFO through recreation.

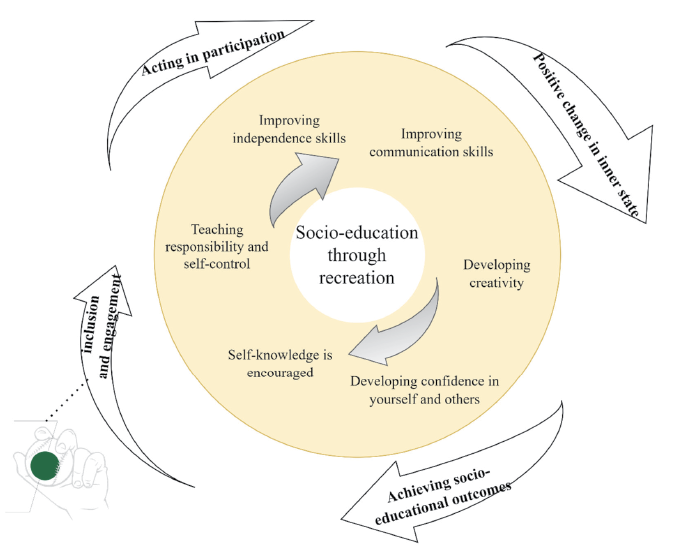

The Inclusive Construct of Social Education of Young People with Fewer Opportunities through Recreation

The data analysis not only highlighted the socio-educational features of recreational activities, such as orientation of activities both towards the target group and the participants who create the activity, the diversity of the spectrum of activities, the diversity of the effects of activities (educational, social, providing wellness and health, etc.), the dynamics of the process, but also revealed the inclusive construct of socio-education through recreation (see Figure 2).

Recreation is a powerful tool and driving force of the entire socio-educational process. The process of learning and socialization is invisible, not always predetermined and planned, sometimes accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful. It can take place individually or in a group, but always occurs through social interactions, and during confrontation can take place in action and participation.

Figure 2

The inclusive construct of social education through recreation (researcher‘s graphic memo).

The first factor that initiates the process of social education is inclusion and engagement. It is when both YPFO and people working with youth get involved themselves or are encouraged by others to get involved in recreational activities. In order to motivate the participants to take part in and continue recreational activities, various targeted strategies are used: engaging the young people in conversations, not pushing them to talk, letting them settle down on their own, etc.

Inclusion and engagement is being a part of the process, which depends on the free decision of the participants, the desire to participate in recreational activities, opportunities for activities to take place, meeting the needs of the participants, the nature of the activities, the goal, and the created leisure environment. A person’s individuality manifests itself in free individual choice, which is the first step towards the process of openness and personality self-creation. This is an important stage that determines the course of the process of social education through recreation. The following question is raised: What happens after the YPFO are involved and engaged in recreational activities?

The next factor that drives the process of social education through recreation is acting in participation. Everyone experiences the same phenomenon differently and perceives it differently, so the effect of the activity is individual. According to the research participants, the positive emotions experienced during the activity change the perception of the environment, participants, and oneself. However, participation in activities alone does not determine successful socio-educational results; a positive change in a person’s inner state is necessary that leads to openness and creating conditions for learning. It is important to mention that participation is determined by the purposefulness of the activities, the hidden socio-educational aim, and the youth worker’s/leisure educator’s power to manage the entire process, organize recreational activities and direct it in different directions.

Another factor that accelerates the whole process is a positive change in the inner state, which is a necessary and determining condition for the significance of socio-educational results. A positive change in the inner state is determined by the joy experienced, important features such as responding to the current state of activity, environmental safety, and developing awareness. The feeling of joy and happiness gives fulfilment, improves mental health, which is often harmed by traumatic experience of YPFO and blocks any positive change. More and more frequent experience of positive emotions fosters a sense of self as a learner, promotes openness, which is a medium for achieving significant results.

The last factor at which one either stops or starts all over again is achieving socio-educational outcomes. Social education through recreation leads to individual changes of YPFO and contributes to the creation of public welfare, since YPFO spend their time meaningfully without knowing it; they educate themselves, socialize; therefore, the casual order of society is not disturbed and it does not cause any tension.

All the factors change each other, covering the area of the process of socio-education through recreation. Sequentially moving, the processes form a connection, the so-called prerequisite for the socio-educational process to take place. Recreational activities that initiate the course of the process become essential, while the informal leisure environment supports and determines the success of the processes.

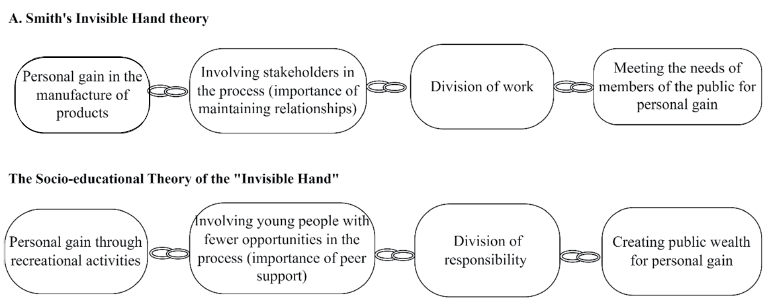

Comparison of Smith’s Economical Theory of the Invisible Hand and the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”

Based on research results a new grounded theory has been constructed – the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” linked to the Invisible Hand theory described by the economist Smith (1776, cited in 2004). According to the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”, a young person with fewer opportunities participates in recreational activities for his own benefit, but his involvement benefits the community as a whole by enabling other young people and youth workers to act accordingly and to meet the needs of the young people’s personal interests. In this way, a socio-educational mechanism is invisible at work: an invisible socio-educational hand that directs the activities of the young people with fewer opportunities to meet the needs of the community and to create social well-being. In the process of socio-education through recreation, the sharing of responsibilities is like an invisible hand (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Comparison of Smith’s theory of the Invisible Hand and the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” (compiled by the authors).

The link between Smith’s Invisible Hand theory and the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” is that they both reveal the invisible workings of processes: markets in economic theory, socio-education in the research. The difference is that Smith is more concerned with the equilibrium processes of the economic market, where the interests of producers and consumers are combined. This theory, although it also deals with the moment of equilibrium, focuses more on the socio-educational process itself. It is noted that in both theories there is a direct correlation between cause and effect. Grampp (2000) argues that in Smith’s theory the formation of social order is directly correlated with the consequences of an individual’s behaviour. In contrast, the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” suggests that the creation of a recreational environment directly influences the activity engagement needs of YPFO. Both division of labour and cooperation require interconnectedness and are more easily understood in small group settings. As Smith (1776, cited in 2004) argues, in small groups, the total number of workers is inevitably small, so that those doing different types of work can be concentrated in one workshop, whereas the division of labour in large groups can be divided into many more parts and is less obvious and therefore less visible (p. 12). Open work with young people in the YPFO region covers larger geographical areas but with fewer participants. It is possible to spend more individual time with them, to establish a closer relationship with them, and to observe the effectiveness of cooperation in organising recreational activities.

The results of the research revealed the importance of maintaining relationships between the participants (youth and youth workers) in order to start a socio-educational process through recreation. Smith also highlights the importance of peer support for the involvement of stakeholders in the process. Hence, in both economics and educational science, the creation and maintenance of relationships throughout the process is important for the invisible process. The economist stresses the division of labour as one of the most important aspects in achieving the most efficient results. Smith (1776, cited in 2004) argues that the division of labour in small groups as well as in large manufactures has the effect of increasing productive power. And in Socio-educational Theory, the division of responsibility is important for significant socio-educational results. It is pointed out that cooperation with specialists and/or recreational professionals from different fields, support from the local government, and partnerships with various institutions and bodies increase the probability of success of socio-educational outcomes.

Smith (1776, cited in 2004), in highlighting the purpose of money, notes two meanings of the term ‘value’: sometimes it refers to the utility of a particular object, called ‘use value’, and other times it refers to the power to acquire goods, called ‘exchange value’ (p. 37). Labour is the first price for all things purchased, and the property acquired in return for labour confers power. However, as Smith (1776, cited in 2004) argues, the mere possession of property does not necessarily confer political power on the owner, but it does confer purchasing power: the ability to dispose of all the labour, all the products of labour, that are currently available in the market. It is pointed out that it is not power, but a variety of circumstances that cause prices to spike up or down. The aspect of power as an invisible force in the socio-educational process, which emerged from the thesis research, reveals a process that attempts to strike a balance between accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful movements, but the socio-educational outcome itself, like the price as discussed by Smith, is dependent on a variety of circumstances, i.e. on the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that determine participation in recreational activities. It is the creation and maintenance of a horizontal relationship between the informal leisure environment and the mutual involvement of the participants in the process that construct the whole process.

Discussion

The process of socio-education through recreation is an inclusive process. The rapid variability of activities and objectives reveals links with the social environment, which indicates the vitality of the process. However, there is always a fundamental element – each factor of socio-education through recreation, which has its own logic, content and objectives. Energy, which also defines the dynamism of the process, is linked in the research to the participants in the process. The mutual involvement of the participants, both the young people with fewer opportunities and the youth workers, and the interconnection between them, leads not only to significant socio-educational outcomes, but also to a balance in the process.

It is equally important to highlight that socio-education through recreation is a holistic process. The rapid change of activities and objectives reveals links with the social environment, which indicates the vitality of the process. It is obvious that each factor of social development through recreation has its own logic, content and objectives. However, there is a core element that drives the whole process. This study highlights the energy injected by the involved actors that defines the dynamism of the process. The mutual engagement and interconnectedness of the participants, both young people with fewer opportunities and youth workers, not only leads to significant socio-educational outcomes, but also to a balance in the process.

The youth worker is referred to as a leisure educator in the research because of the power he or she has to manage the socio-education process. Although Gaventa and Cornwall (2008), drawing on Morris (1984) and Mueller (1992), argue that power can be a means of bridging the inequality gap, the research revealed that power as an invisible force that the leisure educator wields, connects all the actors in the socio-education process. It does not seek authority, but rather to be equal with others, to build relationships, to share knowledge and experience. It should be noted that this process is both complex and random. The complexity is due to the hidden meaning in the socio-educational process, the construction of the leisure educator’s knowledge, and the interconnection of the experience of working with young people with fewer opportunities. The randomness depends on the social inclusive, recreational educational, educational preventive, psychological impact of the created non-formal (leisure) environment on the young person and the experience they have. The findings of the research complement Turner’s (2005) ideas that power is inherent in all social relations, it is a feature of a person’s life and structure, it only exists through action, and it is immanent in all spheres, not influenced by one of them.

It is the agency involved in the research that reveals the experiences and discoveries of the youth in action. Cunningham (2010) emphasizes that the individual consciously anticipates the activities through which they will learn. However, the study highlights that activities during recreation are planned by youth workers, but participants engage in them without the expectation of learning. It is pointed out that learning is not pre-planned and reflective, but that the learner’s consciousness emerges when they reflect on the experience.

The study not only revealed the dynamic nature of the socio-educational process, but also highlighted the factors of the socio-educational process through recreation: engagement, participative action, positive change of inner state, and achievement of socio-educational outcomes. On the one hand, this shows the complexity of the process of socio-education through recreation and reveals different sub-processes that could be focused on when discussing the practical applicability of the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”. The process of socio-education through recreation itself, which includes other sub-processes, depends on the inclusive force of recreational activities, which screws up the whole process and highlights learning through participation in everyday social practice.

The constructivist grounded research strategy is associated with the perception that the characteristics of the research may change at some other time, because society may change, public opinion may change, people’s belief system may change, etc. (Charmaz, 2006). Thus, conducting research in a different context, at a different time, in a different place with a different group of young people, is likely to highlight new categories and thus add to the Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand”.

Conclusions

Social education through recreation is associated with the dimension of informal learning, when learning does not take place in the context of problem solving, but in the environment such as open youth centre that provides the conditions to perceive pleasure as enjoyment through meaningful free time forms, and as well empowers the learner to take greater responsibility for successful learning outcomes. Socioeducation through recreation promotes engagement, increases young people’s openness to change, enables them to solve problems, which develops their self-confidence and trust in others, increases self-esteem, and teaches responsibility, self-control and independence.

The process of social education through recreation consists of the formalised-visible and informalised-invisible sub-processes, which is not direct or pre-planned. The main axis of the grounded theory The Socio-educational Theory of the “Invisible Hand” is management strategy that is presented in the metaphor of the hand, when the purposeful direction of the socio-educational process, or the management of the hand, is present in the accidental or conscious, spontaneous or purposeful movements. Movements of hand help determined by an invisible force which manifests itself as maintained balance and the shared responsibility perceived among the participants in the process. The image of the hand explains the reflective, partially latent, experience-based movements of socio-education through recreation, which is also determined by internal and external factors. This theory would need to be tested and in other contexts of recreational work with YPFO

Aspects of recreation as a recognized social value presuppose a new role of the youth worker as a leisure educator and underpin the socio-educational benefits of working with YPFO in an open youth centre/space. New lines of research are needed to unpack and capture the role of the youth worker.

References

Belhassen, Y. (2021). Work, leisure and the social order: Insights from the pandemic. Annals of Leisure Research, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2021.1964992

Bryant, A. & Charmaz, K. (2019). The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526485656

Charmaz, K. & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.13.4.84.s4

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage.

Crompton, J. L. (2008). Evolution and implications of a paradigm shift in the marketing of leisure services in the USA. Leisure Studies, 27(2), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360801902224

Cunningham, I. (2010). Learning to lead – self-managed learning and how academics resist understanding the processes. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 24(2), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777281011019434

European Union Youth Strategy 2019–2027. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A42018Y1218%2801%29

Garbauskaitė-Jakimovska, J. (2014). Ugdymas dirbant su jaunimu: jaunimo neformaliojo ugdymo kokybės paieškos. STEPP: socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika, 9, 64–80. https://doi.org/10.15388/stepp.2014.0.3776

Gaventa, J. & Cornwall, A. (2008). Power and knowledge. The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2, 172–189. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934.n17

Glover, T. D. (2015). Leisure research for social impact. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(1), 1–14.

Grampp, W. D. (2000). What did Smith mean by the invisible hand? Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1086/262125

Hense, C. & McFerran, K. S. (2016). Toward a critical grounded theory. Qualitative Research Journal, 16(4), 402-416. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-08-2015-0073

Hollingworth, K. E. (2012). Participation in social, leisure and informal learning activities among care leavers in England: Positive outcomes for educational participation. Child & Family Social Work, 17(4), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00797.x

Hurd, A., Anderson, D. M., & Mainieri, T. (2021). Kraus’ Recreation and Leisure in Modern Society. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Hutchinson, S. L. & Kleiber, D. A. (2005). Gifts of the ordinary: Casual leisure’s contributions to health and well-being. World Leisure Journal, 47(3), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2005.9674401

Isik, U. (2018). How to Be a Serious Leisure Participant? (A Case Study). Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(9), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i9.3453

Kleiber, D. A., Walker, G. J., & Mannell, R. C. (2011). Psychology of Leisure. Urbana: Venture Publishing, Inc.

McGuire, J. & McDonnell, J. (2008). Relationships between Recreation and Levels of Self-determination for Adolescents and Young Adults with Disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31(3), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885728808315333

McLean, D. J. & Yoder, D. G. (2005). Issues in Recreation and Leisure: Ethical Decision Making. Human Kinetics. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781492596295

McLean, D. J., & Hurd Kraus, A. R. (2015). Recreation and Leisure in Modern Society. Burlington: Jones And Bartlett Learning.

Nagata, S., McCormick, B. P., & Austin, D. R. (2020). Physical activity as treatment for depression in recreation therapy: Transitioning from research to practice. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 54(1). https://doi.org/10.18666/trj-2020-v54-i1-9745

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

Sivan, A. (2008). Leisure education in educational settings: From instruction to inspiration. Society and Leisure, 31(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2008.10707769

Smith, A. (2004). Tautų turtas (vert. J. Čičinskas). Vilnius: Margi raštai.

Stebbins, R. A. (2018). Leisure as not work: a (far too) common definition in theory and research on free-time activities. World Leisure Journal, 60(4), 255–264.

Stebbins, R. A. (2017). Serious Leisure (2nd edition). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2018.1517107

Surg, J. C. (2014). Education through recreation. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 57(2), 76. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.003114

Torkildsen, G. (2012). Leisure and recreation management (4th ed). London: Routledge.

Turner, J. C. (2005). Explaining the nature of power: A three‐process theory. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–22.

Williams, S. & Keady, J. (2012). Centre stage diagrams: A new method to develop constructivist grounded theory – late-stage Parkinson’s disease as a case exemplar. Qualitative Research, 12(2), 218–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111422034

Zarotis, G. & Tokarski, W. (2020). Theoretical and Sociological Aspects of Leisure Time. Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies, 5(7), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.36348/sjbms.2020.v05i07.002