Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2024, no. 46 (51), pp. 77–90 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2024.46(51).6

Translated Poetry in Late Soviet Latvia: Sporadic modernism and the construction of world literature

Ivars Šteinbergs

University of Latvia

Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art

Krišjāņa Valdemāra street 106-75, Riga, LV1013, Latvia

Email: steinbergs.ivars@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0576-077X

https://ror.org/05g3mes96

Research interests: Poetry, Literary translation, Poetics, History of Latvian literature, Deconstruction, Post-structuralism, Post-colonial studies

Abstract. The article builds upon previous work that has been written about the connection between translation and colonial endeavours (Tymoczko, 1999; Robinson, 2014), as well as the research done in the field of Baltic post-colonialism (Annus, 2018), and focuses on cases of poetic production in Soviet Latvia during the time after de-Stalinization. By surveying data on the publication of books of translated poetry in Latvia after 1956 – when knowledge of Stalin’s terror disseminated, the study reveals how translation was used to strengthen Soviet power in occupied territories. The “world” that was being represented through translation was largely Eurocentric and Russocentric. Simultaneously, from the 1960s onward, several Latvian translators wrote translations and poems that survive both as documents of cultural others, and as testimonies of local noncompliance. These works are imbued with modernist poetics that was unfamiliar to or even condemned by the propagators of socialist realism, the official and ideologically saturated aesthetic promoted by the Soviet regime. The article suggests reading such texts as a kind of sporadic modernism within Soviet Latvia.

Keywords: literary translation; Soviet occupation of Latvia; modernism; Western poetics.

Submitted 1 February 2024 / Accepted 27 May 2024

Įteikta 2024 02 01 / Priimta 2024 05 27

Copyright © 2024 Ivars Šteinbergs. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The ongoing, albeit uneven, process of decolonization across multiple levels of post-socialist countries necessitates a continuous reevaluation of colonial histories. The unwanted spectres that haunt our aesthetic, national, social, and intellectual spheres call for new interpretations of not only the present currents of cultural politics, but also of our interrelated past(s) as well. This is especially relevant considering how “imperial nostalgia” persists and keeps “[shaping] constitutional change” (Partlett and Küpper, 2022, p. 33) in 21st century Russia, a force proven to be a threat to democracy and human life. In recent decades a theoretical framework has been established to describe the Soviet regime as imperial – and therefore colonial –, and the term many have found useful to denote the specifics of this empirical power’s historical behaviour is coloniality (as opposed to literal colonialism) – meaning that, while the structure was not explicitly a centre with colonies, it did however implement strategies of oppression and supervision that are analogous to those of colonialism. In fact, the notion of Soviet coloniality has recently gained traction outside former Soviet republics as Western academics somewhat belatedly echo the work done by local scholars. An example of this is William Partlett and Herbert Küpper’s book “The Post-Soviet as Post-Colonial” (2022). However, in the case of the Baltic countries, much has already been said about the relationships between the occupied territories and their oppressor, be it the writings of Epp Annus on Estonia (2018), Benedikts Kalnačs on Latvia (2011), and Violeta Kelertas on Lithuania (2006) amongst others.

In this article I supplement the discussion on Soviet coloniality in the Baltics by sharing some data regarding a topic that is not only relatively overlooked in research but illuminates the extent of state control in literature as well as the paradoxical tensions within it. It is the subject of translation – the process, result, profession, and cultural building block present in many colonial contexts. Coloniality imposes a system of values, an ethics of right and wrong, true and false, in other words, a world view, a perspective on the world, and perhaps an image of the world itself. Translation is one of the tools used to situate perspectives and construct perception, therefore it seems pertinent to question the clockwork of translation within the Soviet domain. Specifically, I turn to literary translation of poetry and the synthesis of world literature within Soviet Latvia during the later periods of the USSR, and I am asking what can the notion of translation bring to the table when formulating an understanding of Latvia’s history concretely and Soviet coloniality in general? Parallelly, by way of concrete examples and narrowing the focus from a macro level to a micro level, I suggest that the individual practice of poets and translators at work within the larger framework of colonial translation can be read as unconformity, especially when highlighting the indirect correlation between Latvia’s poetic output after 1968 and modernist poetry written beyond the Iron curtain.

1. Constructing the “World”

The Russian-speaking part of Soviet culture has a long and complex history, with logocentrism which includes the practice of translation. As noted by scholars like M. Tymoczko and D. Robinson (Tymoczko, 1999; Robinson, 2014), translation has often served as a tool for colonization. P. Casanova (2007) further demonstrates that literary translation establishes and assigns value, extending the influence of dominant languages and works of literature. “[F]rom the point of view of a major source language, translation permits the international diffusion of central literary capital. By extending the power and prestige of the great literary countries, (...), it broadens the influence of languages and literatures that pretend to universality and thus adds to their supply of credit” (Casanova, 2007, pp. 134–135). The Soviet empire did much to ensure that its literary production, the aspect that was in line with acceptable ideology at least, was widely disseminated across occupied territories. Conversely, it also endeavoured to make sure that the Russian language becomes the locus wherein world literature takes place.

This process, rife with inequalities to begin with, was even more skewed by authoritarian approaches where, as N. Rudnytska explains, “due to a policy of (...) exclusions and admissions, the world literature canon was represented as a single entity spreading ‘universal’ and ideologically appropriate ideas, values, and aesthetics, with Russian literature being its most important part,” adding that “for non-Soviet authors, admission to the canon often meant legitimized appropriation” (2022, p. 39). Legitimized appropriation can be understood both politically and poetically where, on the one hand, unwelcome ideas are concealed, and, on the other, linguistic experimentation, this bourgeoise vagary, is washed away. The quality of translations was also compromised, as N. Kamovnikova notes, “a literary translator in the Soviet Union was permitted to remain monolingual, however contradictory to the professional requirements this may sound” (2019, p. 151). In other words, the translations were commonly written using either bridge languages or interlinear trots, i.e., literal, word-for-word translations done by someone who could read the original but did not work as a professional translator, therefore adding more confusion to the already biased landscape of Russian translation.

It was a field of multiple tensions, not in the least between xenophobia and internationalism, as James Baer asserts: “On the one hand, Soviet Russia did a lot to promote the translation of world literature into Russian. (...) On the other hand, the regime implemented censorship at practically every stage of the publishing process” (2011, pp. 7–9). Although Soviet culture sought diversity by introducing the “other,” it suppressed any “otherness” that might threaten the power structure. The Soviet regime was officially supposed to create a multinational community where the different friendly republics would translate each other’s work as well as canonical global classics. However, translations were still regularly under scrutiny, especially those considered too daring in form or too uncomfortable in theme. It is a coloniality that is always already internally contradictory, it subdues its subjects, and thereby – creates the necessity of resistance. Here, it must be said that such a position, which allows and forbids at the same time, can also be considered a kind of “loophole” in cultural politics, within which translators and poets saw beyond or through their isolated landscape. It is where some poets and translators, being cognizant about the liberated art in the West, saw an opportunity to carry in non-Soviet alternatives to the state-controlled publications.

This is part of what made Latvian translation after the Stalin era, especially in the late 1960s throughout the 1980s, slightly stand out on the backdrop of Russian translation. First, Latvian authors, following the impetus of such figures as Knuts Skujenieks (1936–2022), began to learn foreign languages and work directly with the source material (see: Balode, 2013, pp. 162–170). Second, writers and poets became more aware of the partiality of the literature being translated into Latvian, stifled as it were by the Iron curtain. “[For] a language on the periphery that looks to import major works of literature,” Casanova writes, “translation is a way of gathering literary resources, of acquiring universal texts and thereby enriching an underfunded literature, in short, a way of diverting literary assets” (2007, p. 134). The vocabulary used to describe translation as a kind of economy is similar to how Skujenieks, a polyglot translator and perhaps the most talented Latvian translators of foreign verse, talked about the merits, treasures and prizes translation can give to a language. In 1970, some 30 years before Casanova’s book, Skujenieks writes: “Self-awareness of national culture, understanding of its sources and course is impossible without comparison with other cultures” (1970 (2007), p. 277) and is primarily to be done through translations. Skujenieks is a powerhouse of poetry in translation, he had a knack for creating artistically excellent and formally faithful renderings of such authors as F. García Lorca, G. Mistral as well as folk songs. While he did not openly translate banned authors or engage in dissident activities, his translations, valued for their artistic excellence and formal faithfulness, inspired writers for decades. Skujenieks and his contemporaries sought to transcend the socialist agenda and envision a more inclusive panorama of world literature. Of course, this was easier said than done since coloniality not only enforced limitations on what could or could not be published, but also dictated what could and could not be available, that is – seen, touched, heard of, let alone – read. Latvian-translated poetry during the Soviet period is a kind of cultural translation that marks the textual and metatextual subjection of Latvian culture to repressive Soviet coloniality; Skujenieks’ work is an attempt to gradually escape from it, perhaps in a future to come. In short, Skujenieks and a handful of his contemporaries are more of an exception. Latvian culture in this period, as manifested in translation processes, was predominantly state-controlled, Russocentric, androcentric, and Eurocentric, privileging individuals who suppressed dissent and deviated from patriarchal norms.

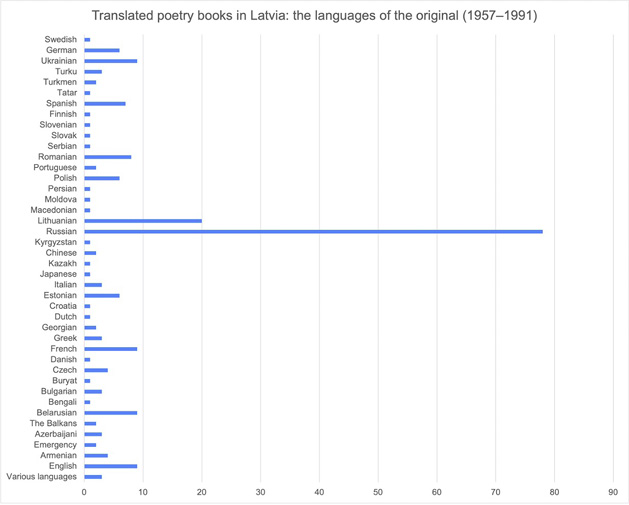

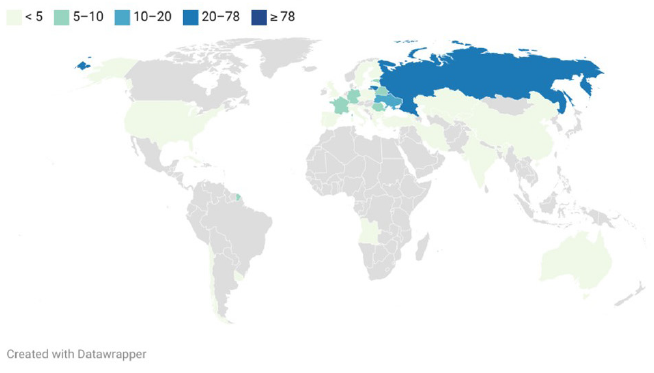

By the end of the 1960s, the number of translated books of poetry in Latvia expanded (Fig. 1), and the relative diversity of languages represented therein can be linked to the efforts of Skujenieks. However, Russian remains the dominant language from which poems are translated. This, at the time, is, of course, related to ongoing russification. That is to say, during this time, between 1957 and 1991, the number of languages doubled in comparison to the period between 1944 and 1956, and thus, the books do represent a wider range of world languages. In total, at least 42 language categories can be found in the translated books of poetry in this period. Most of them in terms of titles published, however, are Russian (at least 78 titles) and Lithuanian (20 titles). A significant part is also made up of Ukrainian, English, Belarusian and French languages (each with at least 9 titles). This situation is consequently evident in the territories whose poetry Latvian translators chose or were forced to translate. Approximating where the books published in late Soviet Latvia originated and linking that to modern territories, it can be seen that, despite greater territorial diversity, the territory of Russia is obviously represented far more often – with 74 titles in this period (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Translated poetry books published in Latvia: the languages of the original, 1957–1991.

Fig. 2. Territories in Latvian poetry translation, 1957–1991.

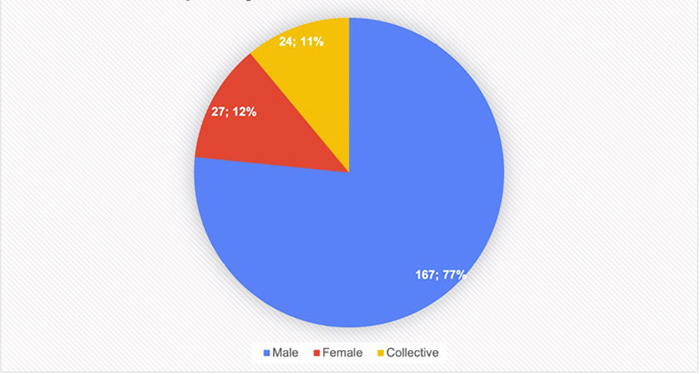

It is noteworthy that out of all the 218 books of translated poetry published between 1957 and 1990, three-quarters were authored by men. However, the number is probably higher since in the books in which collectives are printed, the majority are also male. Namely, there are 167 books written by male authors, 27 by females and 24 by both (fig. 3). Such disproportion in itself is not a surprise. Still, it allows us to demonstrate how certain unequal practices, strengthened socially and politically and therefore taken for granted, are manifested and spread in cultural spheres, including translated literature.

Male and female authors in translated books

of poetry in Latvian, 1957–1991

Fig. 3. Male and female authors in translated books of poetry in Latvian, 1957–1991.

Such biases in representation are not unique to Soviet Latvia. The “world” that is being represented in world literature classes, English-speaking universities, conferences, and elsewhere is traditionally androcentric and Eurocentric; in this case, it leans heavily towards Russia. However, in the case of Latvia in the later part of the 20th century, what is interesting is how this bias not only arises from an internally contradictory power structure but also stimulates decolonizing efforts amongst free-thinking Latvian artists. Even politically accepted authors were reacting to the need to broaden Latvian translation. For example, in an article published in 1974, Latvian poet I. Ziedonis emphasizes the importance of local poetry of what he calls “language workers”, the translators. According to him, the ability to compare poetry internationally has the potential to be mutually enriching. Ziedonis asks whether the translators are “meeting the demands of today’s multicultural culture?” He knew the lack of translators from Flemish and Yugoslav nations, Romanian, Hungarian, Hindi, Bengali, classical, and other languages. “It would be normal if there was an expert from each language, if not a translator, then at least an informer, a rapporteur. It would be even more normal [...] if there were more translators from each language, if there was creative competition in the work of translators” (1999, pp. 63–64). This statement rings out as true even today, but it was the literary scene of 1970s Soviet Latvia from which it sprang, a time when there was more at stake when objecting to the status quo.

2. Smuggling in Modernism?

Ziedonis, along with such figures as V. Belševica and M. Kroma, can be considered, to an extent, as regime-tolerated modernists. However, they were not described as such at the time. Their writing style, along with – and perhaps more importantly – the poetry and translations of their counterparts who suffered repressions more directly, raises the issue of how modernism was perceived and appropriated (if at all) in Latvian poetry during the occupation. This issue of the place and use of literary modernism in Latvian poetry presents counterforces that must be untangled to articulate its specificity theoretically. Therefore, I would like to mark three interrelated fields of paradoxical tension that describe the cultural context of Latvia’s past. The third point will present three poems that perhaps will illuminate some ideas that follow.

First, the problem of periodization arises. The period in question spans nearly 50 years and is not homogeneous. There are crucial differences between the early post-war years and later decades, with the same power structure that vehemently opposed modernism under Stalin gradually easing censorship, creating opportunities for its acceptance. Although, for the most part, for Latvian writers under Soviet rule, the possibility of becoming directly influenced by or advancing modernist literary techniques was stifled. It is widespread in Latvia and officially encouraged after the Second World War to disown and belittle modernist poetics, regardless of definition, and to celebrate instead the victory and splendour of socialist realism, which had, according to the politico-mythological narrative of the time, defeated Western degradation and is leading the way to socialist utopia. “The twin sister of the decay of the realist tradition is the glorification of modernism of all kinds and the aversion to it,” says one V. Kalpiņš (1958, p. 4).

Such notions continued to appear in the press until the 1970s: “Socialist realism has fundamental disagreements with modernism, irreconcilable contradictions. (...) History shows that socialist realism conquers modernism, that socialist humanism crushes the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois misanthropy born in the swamp of today’s rotting capitalism” (Krauliņš, 1971, pp. 127–128). This is in itself a contorted proposition, seeing as many modernist writers had Marxist backgrounds; for example, Latvian scholar S. Ignatjeva has researched the epithets associated with modernism in Latvian periodicals and found that, when talking about authors or groups that do not blend well with local ideology, the modernism is usually “parasitic” or, in milder cases, “complex”. In contrast, when talking about contexts closer to home, the modernism discussed is “humane” (2022). Some exceptions were not critical towards modernism, yet they are written with the utmost precaution; for example, in T. Zālīte’s introduction to an essay by T.S. Eliot, the word “modernism” is not mentioned (1974, p. 14). In 1966, however, Dz. Kalniņa published an article devoted to Western literature in which she defines the principles of what she calls “new poetry”, i.e., “renouncing banalities and well-trodden paths, not being afraid of non-poetic themes, expressions, and words, eliminating stereotypical comparisons, expanding the boundaries of metaphorism, utilizing the multiple meanings, rhythm, and sound formation of each word” (1966, p. 153). From a contemporary standpoint, her description reads as an attempt to tame or domesticate foreign aesthetics and justify some trends in Latvian poetic practice.

The second paradox is related to translation and the problem mentioned above of xenophobia and internationalism. The poets and translators, who may not even have been fully cognizant of the liberated art of the West, tended – knowingly or unconsciously – to “smuggle” in literary devices akin to modernist poetry, thus creating a kind of sporadic, epiphanic modernism within the otherwise inflexible artistic landscape. An example is Federico García Lorca’s collection of poems “Kliedziens” [“The Scream”], published in 1971 in Knuts Skujenieks’ translation. In this collection, edited by Tamara Zālīte, one can read several poems that give Latvian readers an idea of one of the best-known authors of high modernism, whose works combine surrealist influences with Spanish folklore, original thinking, vivid imagery, and expressive metaphors. Lorca’s novelty in the context of Latvian literature is primarily related to the poetic infrastructure of his verse, the syntax, tropes, and ways in which images are organized in strophes. It is not unlikely that Skujenieks was attracted by the connection between Lorca’s poetry and Spanish folklore.

Along with the concept of duende (the spiritual and creative movement found in songs), which Lorca himself emphasized in his lectures, his poetry was inspired by folk songs. Skujenieks was interested in the connection between the individual and the national. Reading Lorca’s poetry, one can see both the influence of folklore and the unique imagination that is local in symbolism and national – or global – in thematic scope. Skujenieks reproduced Lorca’s writing, balancing between purity of form and clarity of the message:

Ai, Hārlema! Hārlema! Hārlema!

Nav skumju, ko pielīdzināt tavām nomāktām acīm,

tavai asinij, drebošai melnajā aptumsumā,

tavai kurlmēmai granātakmeņa varmācībai krēslainā ēnā,

tavam dižajam karalim – arestantam šveicara drānās!

*

Naktij ir plaisa un rāmas marmora salamandras.

Amerikāņu meitenes nēsā savos vēderos bērnus un naudu,

un zēni noģībst pie laiskuma krusta.1 (Lorka, 1971, p. 160)

These are lines from the poem “Ode to the King of Harlem”, which appears in “A Poet in New York”, highlighting the peculiarity of Lorca’s vision. This heightened rhetoric combines traditional images (heart, blood, veins, wind, night) with the contemporary, the urban and the unusual (crocodiles, marble salamanders, a cross of laziness). Such lines as Naktij ir plaisa un rāmas marmora salamandras [The night has a crack and calm marble salamanders] infuse Latvian poetry with imagery that is typical of Western surrealism and is therefore far less known in the Latvian SSR. Hence, preempting the turn to postmodernist experiments, ambiguity and density in images in the 1990s, notorious ambiguity and density were already introduced into Latvian literary life in the 1970s along with Skujenieks’ García Lorca.

Finally, the third and final field of tension, on which I shall expand more by giving concrete examples from the 1970s and 1980s when, amidst political shifts, the awareness of an unrealized poetic potential circulated more openly. Much has been said in Latvian scholarship about the art of being unproblematic on the surface but using euphemisms and subtle subtexts on a deeper level to bypass censorship and address readers who are sensitive to irony and implicit acknowledgements of oppression. Indeed, for many, it was translations that allowed them to seemingly conform to nomenclature while simultaneously seeking the unfamiliar, and several poets did become translators to broaden their own creative worldview, in effect enmeshing their own talent with both compliance to Soviet demands and the devices of Western poets; producing writing that can legitimately be characterized with the term ‘hybridity’.

However, it is the strand of original poetry that was not covertly perceived as anti-Soviet but rather non-Soviet, and therefore – more engaged with aesthetic heights rather than social commentary, to which I wish to devote critical reflection. An example of this is the poetry written after the publication of the anthology of modern French poetry “Es tevi turpinu” (“I continue you”) compiled by M. Silmale in 1970. As E. Eglāja-Kristsones writes, analysing the arrival of Western literature behind the Iron Curtain: “It shows the conflict between rules ‘from above’ and initiatives ‘from below’” (2012, p. 349). The collection was perceived as a breath of fresh air, and the resonance of this book continues even today, with poets such as R. Mežavilka, A. Auziņa, and A. Viguls all having referenced the anthology’s texts in one way or another. However, at the time of publication, it was belatedly perceived as a dangerous mistake that should be punished. In the 1970 editorial review of the “Liesma” publishing house, it is written:

The most unsuccessful book in 1970 was a selection of French poetry. The editors made a mistake by publishing Maijas Silmale’s objectivist introduction (...), which disorients the readers. The head of the editorial office was reprimanded by order of the Press Committee for the ideological mistakes made in the collection. This case reminds us once again that the content of the books should be given a lot of attention, and every place that has raised doubts should be carefully considered and checked. When working with translations from foreign languages, problematic places in the text should be compared with the Russian edition (LNA LVA 478-11-61).

Silmale’s “objectivist introduction”, which “disorients readers”, is one of the few texts published in Soviet-era Latvia that contextualizes modernist poetry without being soaked in Marxist ideology. Silmale’s case is an example of an artist’s struggle against power poetically and biographically, having been arrested and unjustly sentenced to 10 years of correctional labour in a colony in 1951 for participating in the so-called “French group”.

The anthology contains the works of 22 French poets, including A. Rimbaud, P. Valéry, P. Éluard, G. Apollinaire et al., and its importance is evident in original poetry, for example, a fragment from B. Cendrars’ poem “Easter in New York”, here in Cristina Viti’s translation:

Lord, it’s an old book I open and read

on the day of your Name. Your Passion, your deed,

your anguish, your effort, your words so humane

weep down in the book like sweet gentle rain.

It is an old story a pious monk told.

He wrote of your death in letters of gold

In a missal he rested upon his knee

working slow, working steady, every day of the week (...) (Cendrars, 2000)

After reading this poem in 1975, the Latvian poet Juris Kunnoss wrote “After Blaise Cendrars: Christmas in Riga”:

Nāk auxtums. Hipijhauzam logi tumst.

Ak, maigās balsis, vainīgās, kas sēro tur par mums,

par Tevi, Dieva dēls, kas varbūt tikai cilvēx.

Vai tikai cilvēx? Tieši tāds ir cilvēx

ar visām savām ciešanām, ar pasaul’s skumjām acīs…

Kas acīs ieskatās, tas tā vairs nepasacīs (...)2 (Kunnoss, 2008, p. 222)

Here, we may read a direct reference to Cendrar’s poem and witness the occasion when Western poetry openly inspired Latvian writing despite the original text being considered unwelcome. It is a stylization that mixes French modernism with Soviet imagery and a kunnossian vocabulary.

There are many more occasions when the connection to specific authors or foreign stylistics is not explicitly stated. These poems are like different counterparts outside of the Soviet sphere, despite no officially known relation or documented proof that the Latvian author read the Western texts that may or may not have been allowed publication in Latvia. These poems have an aesthetic correspondence to those written in the West, irrespective of biographical context. Consider the early poetry of J. Rokpelnis, which may be viewed considering the early writing of Ch. Simic. In his last book, written in Soviet times, Rokpelnis writes:

nāc pie manis par virēju

laukakmeni es īrēju

laukakmens tik savrups

katrs viņā reiz sadrups

nākšu pie tevis par mirēju

nekļūt man akmensnirējai3 (Rokpelnis, 2022, p. 269).

Here is Simic, a decade earlier:

Go inside a stone

That would be my way.

Let somebody else become a dove

Or gnash with a tiger’s tooth.

I am happy to be a stone. (...) (Simic, 2013)

The meeting points in these two texts reach farther than just that. They evoke analogous imagery (a stone and its anthropomorphic characteristics). These authors have an unconfirmed affinity – a typological link between Rokpelnis’ grotesque sensibility or absurdist narratives and Simic’s potent and concrete allegories.

Finally, consider a fragment from U. Bērziņš’ poem “Requiem”, a prose poem with graphical elements written in ١٩٨٩ and dedicated to Latvian soldiers shot in Afganistan:

Pie velna tos vārdus, kad lielījos, ko es zinot un darot, -

kā tik daudz klusuma uzrakstīt, ko miljonu zvaigžņu barot, tu,

Juri, Jāni, tumsā tu lēnām ar tukšumu sarod, klusuma ozoli tum-

sā aug, klusuma stumbri sāk

zarot pār hospitāļiem, pār

hospitāļiem vakars kā liela

plauksta, es tavai rokai pie-

dūros, roka jau bija auksta, ģitāra spēlē pus debesī, miljons

zvaigžņu jau kājās, samierinies ar neesamību, drīz tu lidosi

mājās, tam es ticu, un man ir skaidrs: tu neprati Šveiku mētāt (...)4 (Bērziņš, 2004, p. 326)

A prolific translator, having worked with multiple languages and an array of styles, including beat poets and futurists, Bērziņš’ “Requiem” is a powerful example of Latvian modernism, shining through at the very end of the Soviet empire. It is a poem that utilizes the materiality of the printed text, thus suggesting the words of S. Mallarmé, one of the figures who catapulted Western modernism into the 20th century: “The intellectual armature of the poem is concealed and resides – takes place – in the space separating the strophes and in the blank spaces in the paper; significant silences as beautiful to compose as the actual lines” (Mallarmé in Bruns, 2001, 114). When reading Bērziņš’ poem, M. Rižijs notes: “The three empty spaces become a meaningful image – the dead soldier’s [...] oak tree of silence and a graphic metaphor for the meaningful, finally written silence that comes when the last lines of the “Requiem” resound” (Rižijs, 2011, p. 13). The poet himself has described the spaces as “three explosions tearing piece by piece from [my] Being.”5 As with the blank, torn-out pieces in the poem, so in the stream of modernist literature in Soviet Latvia, there was a kind of forced discontinuity, within which authors sought out means of looking beyond the borders of officially acceptable aesthetics and authors who wrote in ways that shone through the layer of ideological saturation.

Conclusion

Further research must better contextualize the jittery continuum of Latvian modernism within a larger framework of World literature since the selected examples imply that Latvian poetry in the Soviet era is a testimony to the plurality and simultaneity of different modernisms. They demonstrate the inner paradoxicality of Soviet coloniality, that, on the one hand, translated poetry, in essence, leans towards diversity by introducing other cultures to the local discourse. On the other hand, all otherness that threatens the non-inclusive matrix of power is suppressed through censorship or other means. The Soviet era is revealed as a time of simultaneity of temporalities in Latvian society, to wit: the urban modernity/modernism of the socialist project co-existing parallelly with a secret fascination with the liberated art of the capitalist world. Various authors and readers conformed to nomenclature on the one hand and sought out Western influence in different forms on the other. This double consciousness is expressed in poetry and translation, where many poets sought to imbue their work with non-Soviet subtexts and/or offer readers an alternative to the common propaganda present in most state-controlled publications. It is a form of literary contraband that strives to introduce artistic currents from the other side of the Iron Curtain into the national discourse – a process that necessarily occurred sporadically.

Paying closer attention to the translation and its many directions and forms, when considering Soviet Latvia can expose both stark contrasts and blurred lines. I believe that there is much to gain by framing translation as an important factor in the domineering efforts of the Soviet Union on a macro level and the creative efforts to resist it on a micro level. As an active participant in a literary economy, even in totalitarianism, translation is a field of negotiating power relations for translators, censors, authors, readers, and more. This is due to the unique character of translation, which can simultaneously show and hide, open possibilities of expression, and become reduced to a mechanism of indoctrination. The research noted here emphasizes the lively potential of including and exploring the notion of translation within the context of Soviet coloniality. The Latvian context offers some clues that point towards possible conclusions, of which the most important seems to be that translation is never neutral – neither the practice nor the results, neither the controlled propagation of it nor the quiet writing of it – it is always closely related to political stances. Translation inevitably paints a partial picture, a selective and fragmentary world. However, it often conjures up an illusion of objectivity and fairness. Hopefully, histories such as that of Latvia can make us stay vigilant and attentive to the deceptive “truths” of modern-day empire, be it Russia, global capitalism, or any system that limits more than liberates.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the project Narrative, Form and Voice: Embeddedness of Literature in Culture and Society (No. VPP-LETONIKA-2022/3-0003).

Translations of Latvian poems provided by Ieva Lešinska.

References

Annus, E., 2018. Soviet Postcolonial Studies: A View from the Western Borderlands. New York: Routledge.

Baer, J., 2011. Introduction: Cultures of Translation. In: Contexts, Subtexts and Pretexts: Literary Translation in Eastern Europe and Russia. Eds. J. B. Baer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Balode, I., 2013. Knuts Skujenieks – viens no latviešu atdzejas skolas aizsācējiem. [Knuts Skujenieks – one of the founders of the Latvian School of Poetry Translation.] In: Tulkojumzinātne. Eds. I. Kačāne, O. Komarova. Daugavpils: Daugavpils University Publishing House “Saule”, pp. 162–170. [In Latvian].

Bērziņš, U., 2004. Dzeja [Poetry]. Riga: Atēna. [In Latvian].

Bruns, G. L., 2001 (1974). Modern Poetry and the Idea of Language: A Critical and Historical Study. Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press.

Casanova, P., 2007. The World Republic of Letters. Trans. M.B. DeBevoise. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

Cendrars, B., 2000. Easter in New York. Trans. C. Viti. Modern Poetry in Translation, 16. Available at: <http://poetrymagazines.org.uk/magazine/record71a1.html> [Accessed 1 February 2024].

Eglāja-Kristsone, E., 2012. Filtered through the Iron Curtain: Soviet Methodology for the Canon of World (Foreign) Literature and the Latvian Case. Interlitteraria, 17, pp. 341–351. https://doi.org/10.12697/IL.2012.17.27. Available at: <https://ojs.utlib.ee/index.php/IL/article/view/IL.2012.17.27/952> [Accessed 1 February 2024].

García Lorca, F., 2008. Poet in New York. Trans. P. Medina and M. Statman. New York: Grove Press.

Garsija Lorka, F., 1971. Kliedziens [The Scream]. Trans. K. Skujenieks. Riga: Liesma. [In Latvian].

Ignatjeva, S., 2022. Sarežģīts, demokrātisks, parazītisks un humāns: modernismu raksturojošie apzīmējumi un termini padomju laika latviešu kultūras periodikā [Complex, democratic, parasitic and humane: designations and terms characterizing modernism in Latvian cultural periodicals of the Soviet era]. Presentation in conference “Vārds un tā pētīšanas aspekti” [The Word and Aspects of Its Study].Liepāja University, Nov. 24–25. [In Latvian].

Kalnačs, B., 2011. Baltijas postkoloniālā drāma [Baltic Post-colonial Drama]. Riga: LU LFMI. [In Latvian].

Kalniņa, D., 1966. Attālumi tuvinās [Distances become closer]. Karogs, 5, pp. 146–153. [In Latvian].

Kalpiņš, V., 1958. Vēstules no Viņpasaules, otrā vēstule / Par “letiņiem”, viņu dzīvi un darbiem. [Letters from the Otherworld, the second letter / About “letiņi”, their lives and works]. Literatūra un Māksla, 46, p. 4. [In Latvian].

Kamovnikova, N., 2019. Made Under Pressure. Literary Translation in the Soviet Union, 1960–1991. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

Kelertas, V. ed., 2006. Baltic Postcolonialism. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

Krauliņš, K., 1971. Sociālistiskais reālisms un modernisms [Socialist realism and modernism]. Karogs, 4, pp. 122–131. [In Latvian].

Kunnoss, J., 2008. Blēža Sandrāra motīvs: Ziemassvētki Rīgā [After Blaise Cendrars: Christmas in Riga]. In: Jura Kunnosa “X” [The “X” of Juris Kunnoss]. Eds. A. Aizpuriete, S. Moreino. Riga: Neputns, pp. 221–222. [In Latvian].

LNA LVA 478-11-61 – Latvijas Nacionālais arhīvs, Latvijas Valsts arhīvs 478-11-61.

Partlett, W., Küpper, H., 2022. The Post-Soviet as Post-Colonial A New Paradigm for Understanding Constitutional Dynamics in the Former Soviet Empire. Edward Elgar Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781802209440.

Rižijs, M., 2011. Ulda Bērziņa dzejas poētika (laika un telpas aspekts) [The Poetics of the Poetry of Uldis Bērziņš (Aspects of Time and Space)]. Ph.D. University of Latvia. [In Latvian].

Robinson, D., 2014. Translation and Empire. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

Rokpelnis, J., 2022. Raksti [Collected Works]. Vol. 1. Ed. I. Šteinbergs. Riga: Neputns. [In Latvian].

Rudnytska, N., 2022. Translation and the Formation of the Soviet Canon of World Literature. In: Translation Under Communism. Eds. C. Rundle, A. Lange, D. Monticelli. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 39–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79664-8.

Simic, C., 2013. New and Selected Poems (1962–2012). New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Skujenieks, K., 2006. Par parindeni. In: Raksti [Selected Works]. Vol. 6. Riga: Nordik. [In Latvian].

Tymoczko, M. 1999. Post-colonial writing and literary translation. In: Post-colonial Translation. Theory and practice. Eds. S. Bassnett, H. Trivedi. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 19–40.

Zālīte, T., 1974. Dzejas sociālā funkcija [The Social Fuction of Poetry]. Literatūra un Māksla, 39, p. 14. [In Latvian].

Ziedonis, I., 1999 (1974). Valodu darbi [The Works of Language]. In: Raksti [Collected Works], 10. Riga: Nordik. [In Latvian].

1 Oh Harlem! Harlem!

There is no anguish compared to your oppressed reds,

to your blood shaken inside the dark eclipse,

to your garnet violence, deaf and mute in the shadows,

to your great prisoner king in his janitor’s uniform.

The night had a crack and quiet salamanders of ivory.

The American girls

carried children and coins in the belly

and the boys fainted stretched on the cross. (Garsija Lorka, 2008, p. 52.).2 Cold is upon us. Hippy House’s windows darken.

O, voices, gentle, guilty, they grieve for us – hearken,for you, o Son of God, who’s maybe just a man

Just a man? Yes, exactly like a manwith all the suffering and sadness in his eyes…

Who gazes into them won’t say it is otherwise. (...)3 come to me and be my cook

see the fieldstone that I tookthis stone is not at all humble

into it we will all have to crumbleI’ll come to you and do my dying

but I won’t do any stone-diving4 Fuck those words when I boasted how much I knew and could do:

how to write so much silence for the millions of stars to chew, you,

Juris, Jānis, in the dark you slowly get used to the void, the oaks of si-

lence grow in the dark, the trunks of silence begin

to branch over hospitals, over

hospitals the evening spreads a large

hand, I touched your hand, and it was al-

ready cold, the guitar sounds through the sky, a million

stars rise up; get used to nonbeing, soon you’ll fly homeward;

one thing I believe, I’m more than certain: you made a poor

good soldier Schweik […]5 From an e-mail (Marians Rižijs’ private archive).