Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2022, no. 42 (47), pp. 76–93 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2022.42.47.110

A Contemporary Free Verse from American and Ukrainian Readers’ Perspectives

Olga Kulchytska

Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University

Faculty of Foreign Languages

Shevchenko str. 57, 76018 Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Email: olga.kulchytska@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9992-8591

Research interests: contemporary poetry, pragmatics, theory of communication

Iryna Malyshivska

Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University

Faculty of Foreign Languages

Shevchenko str. 57, 76018 Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Email: malyshivskairyna2018@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5544-5889

Research interests: intertextuality, translation studies, contemporary literature

Abstract. The study presents an experiment aimed at discovering similarities and differences in how American and Ukrainian participants perceived contemporary free verse. Three poems were examined from the perspectives of intertextual/infratextual/intratextual context dimensions. The presence of intertextual characteristics – reflecting social reality and metaphoric content – was recognized by the majority in both groups of participants, yet across the groups, there were differences in the degree of value placed on each characteristic. Differences in views on the infratextual contexts reflect the variability of functions performed by the initial/intermediate/closing parts of the poems. As regards intratextual context dimension, there were significant similarities in the participants’ views on the imagery, in the constructed text-worlds, emotional responses, interpretations, and encountered difficulties. The analysis of the intratextual contexts of the poems indicates that some texts may drive readers’ interpretations, thus reducing the role of culture in their reception.

Keywords: free verse; intertextual/infratextual/intratextual context dimension; imagery; text-world, culture.

Submitted 30 November 2021 / Accepted 12 July 2022

Įteikta 2021 11 30 / Priimta 2022 07 12

Copyright © 2022 Olga Kulchytska, Iryna Malyshivska. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Interpreting poetry involves knowledge of linguistic features, literary conventions (Hanauer, 1998), and cultural knowledge. This study presents the results of an experiment on the reception of three contemporary free verse poems by American and Ukrainian participants (readers).

In their cross-cultural studies on readers’ emotional responses to Annabel Lee and The Lake by E. A. Poe, Anna Chesnokova et al. (2009, 2017) show that they are largely culture-specific. Yehong Zhang and Gerhard Lauer (2015, 2022) state that receptions of Chinese and German fairy tales and classical poetry by Chinese/German readers differ, but the familiarity of textual worlds facilitates comprehension.

The questions that prompted our research were: to what extent is the reception of contemporary free verse culture-dependent? are there “universal” aspects in its reception? The initial hypothesis was that readers’ receptions would depend more on text-worlds and themes than their cultural background.

Poetry is approached from the perspectives of the genre (Hanauer, 1998); polyvalence conventions, metaphoric content, making a significant point (Peskin, 2007); symbolic interpretation (Svensson, 1987); Text World Theory – TWT (Gavins, 2007); schema theory (Semino, 2014); difficult poetry (Steiner, 1978; Yaron, 2002, 2003; Castiglione, 2017, 2019); expert-novice comparison (Peskin, 1998); feelings and thoughts (Eva-Wood, 2004), and others.

The aim of this study is to find out whether there are significant differences between the views of the American (US) and Ukrainian (UA) readers on three contemporary free verse pieces. Our tasks are to compare: (a) the readers’ views on the suggested intertextual and infratextual context characteristics; (b) the readers’ interpretations of the poems’ intratextual contexts. The latter involves the use of the think-and-feel-aloud (TFA) method (Eva-Wood, 2004) and analysis of the participants’ interpretations from the TWT (Werth, 1999; Gavins, 2007) perspective.

1. Theoretical background

Free verse has deep roots – from the Old Testament and early Greek poetry to Walt Whitman and the avant-gardes of the 20th century, including Imagism and Surrealism (Stockwell, 2017; Childs, Fowler, 2006, p. 94). It is a poetic genre, the genre being the “codification of discursive properties” and “the point of intersection of general poetics and literary history” (Todorov, Berrong, 1976, pp. 162, 164). Its properties are the absence of set meters, irregular rhyme, syntax-/cadence-centered prosodies, the superseding of the line by the strophe and variations in line length (Childs, Fowler, 2006, p. 95; Wales, 2014, p. 177).

Roman Jakobson (1960) states that the poetic function – orientation towards the message, foregrounding form of expression, making reference ambiguous – is the essence of verbal art. A deviation from the linguistic norm in poetry can be a marker of specific significance (Riffaterre, 1978, pp. 2–3). Types of poetic difficulty are analyzed by George Steiner (1978); agents that signal difficulty by Davide Castiglione (2019, pp. 95–156).

Poetry fulfils its function by dealing with essentials, making significant statements and expressing a significant attitude, resisting automatic understanding, implying multiple understandings, involving symbolism, by being coherent and metaphorical (Svensson, 1987, pp. 479, 498–500; Hanauer, 1998, p. 67; Peskin, 1998, p. 254; Peskin, Wells-Jopling, 2012).

Context is a factor in poetic interpretation (Svensson, 1987, p. 479). The four context dimensions are: extratextual (situational), intertextual (relationship between texts), infratextual (part to whole relationship within the text), intratextual (co-text) (Meibauer, 2012, p. 11).

Poetry is often interpreted through the TWT cognitive framework. A text-world is “a deictic space, defined initially by the discourse itself, and specifically by the deictic and referential elements in it” (Werth, 1999, p. 180). World-building elements (world-builders) indicate time/place/objects/entities in literary worlds; function-advancing propositions tell the story. Literary texts, with their world-switches and modal worlds, offer a range of possible readings (Werth, 1999; Gavins, 2007; Gavins, Lahey, 2016); yet the text reveals domains of knowledge necessary for its interpretation (Stockwell, 2009, p. 6).

This study analyses the US/UA readers’ views on the intertextual/infratextual/intratextual contexts of three contemporary free verse poems. Structurally the study follows Jörg Meibauer’s (2012) outline of context dimensions. From a cognitive perspective, intertextuality is retrieving relevant information from one’s mental store of narrative schemas and establishing a connection between narratives (Mason, 2019). Intertextuality operates across and within genres. We address it from the latter perspective and discuss two intertextual characteristics of the poems: reflecting social reality and metaphoric content, which, in terms of Jessica Mason (2019, pp. 77–81), can be viewed as generic unmarked. Infratextual contexts are addressed through the analysis of three characteristics: the initial part of a poem presents world-builders; the intermediate part tells the story; the closing part is explicated/implicated the conclusion. TWT is the underlying framework of intratextual co-text analysis with a focus on imagery, text-worlds, and readers’ emotional responses. Our initial assumption was that similarities in the US/UA receptions might prevail over differences, given that the chosen poems aim at general human themes.

Imagery, a form of description that appeals to readers’ senses, is viewed in this study as an intratextual characteristic. Imagery is the subject of much research. Anežka Kuzmičová (2013, 2014) discusses the prototypical types (enactment, description, speech, rehearsal) of mental imagery evoked by narratives from an embodied cognition perspective. Kuzmičová (2012, p. 275) states that imagery from visual descriptions is not correlated to perceptual experience and resembles the experience of voluntary visual images. Michael Toolan (2016, pp. 150–156) argues that mental picturing is a consequence of textual comprehension, vague mental images, rather than representations of textual situations in narratives. The “imageability of of single mentions and descriptions in poetry as affected by grammatical, syntactic and semantic choices” is studied by Castiglione; his model of imagery is hinged on two aspects of image construction: “the proximity/distance scale…; 2. the resolution scale, related to coarseness or level of detail of the image” (Castiglione, 2020, pp. 48, 55).

2. Method

Study design. Intertextual/infratextual/intratextual context dimensions outlined by Meibauer (2012) are adopted as a structural schema for this study. We suggest two intertextual and, tentatively, three infratextual context characteristics of the poems under discussion. TWT is adopted as the framework for the analysis of the intratextual co-texts. The latter are examined in terms of imagery and text-worlds; the readers’ emotional responses are considered too.

Table 1. Study design

|

Questionnaire |

|

1. intertextual context characteristics 2. infratextual context characteristics |

|

Oral discussion: TFA method |

|

3. intratextual context dimension |

(Characteristics 1.1–2.3 are present in metrical poetry, too; characteristics 2.1–2.3 are possibly typical of lyrical/romantic poetry.)

In the top-down part of the experiment, the participants are to read the poems and mark detected characteristics in the questionnaire. Our objective here is to increase the readers’ (non-linguists’/-philologists’) awareness of these literary phenomena that will assist them in producing a plausible interpretation of the poems.

In the bottom-up part, the participants are to discuss each poem orally. The objective is to explore their analytical reading skills and involvement.

Participants. To recruit US participants, we addressed the Institute of International Education, Kyiv Office; the American Council for International Education in Ukraine; an American Fulbrighter who used to teach at Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, Ukraine. They recommended potential participants. 14 persons, 11 in their 20s–40s and 3 in their 50s–70s, agreed to take part in our experiment.

14 UA participants were selected directly by the researchers of this article, making sure that the age pattern reflected that of the US group.

The oral answers of the older US/UA readers provided extra arguments concerning our initial assumption; the data from their questionnaires were not included in the analysis so as not to disrupt the age homogeneity of the groups. 11 US and 11 UA readers aged between 23–43 represented a variety of occupations other than philology/linguistics (the idea was that poetry’s target audience is heterogeneous). All participants had a university degree. The self-assessed level of English language proficiency: the US readers: 11 – Proficient; the UA readers: 4 – Proficient, 4 – Advanced, 3 – Upper Intermediate.

Table 2. Study participants

|

Culture |

Number of participants |

Age |

Gender |

|

US |

11 |

24–43 |

7 males, 4 females |

|

UA |

11 |

23–41 |

9 males, 2 females |

Materials. The three poems – How everything is by Michael Swan (2011), The long hall by Stevie Howell (2018), February 29 by Jane Hirshfield (2012); Poems 1, 2, 3 henceforth – make significant social/emotional statements, allow more than one interpretation, have metaphoric content. They are accessible: out of a range of linguistic indicators of difficulties at the levels of graphology, morphology, grammar, syntax, semantics, and discourse (Castiglione, 2019, pp. 102–156), only lack narrativity and connectives in one poem, and metaphors may hamper comprehension.

Poem 1 is an internal focalized description of rock climbing to find a car park, toilets and a café at the top. Poem 2 is a first-person narrative about the struggle to regain lost health. Poem 3 compares February 29 to miscellaneous things, from a second cup of black coffee to a letter re-readable after its writer has died. All italicized units in this article come from Poems 1, 2, and 3 (see Appendix 1).

Poems 1 and 2 are semi-narrative: sequences of “non-randomly connected events” (Toolan, 2001 [1988], p. 8) that display no “linguistic features typical of narrative fictional texts: third person pronouns; proper nouns; past tense verbs” (Castiglione, 2017, p. 111). Poem 3 is non-narrative: there are several third-person subjects, but “no spatiotemporal anchoring and … the events appear randomly connected” (Castiglione, 2017, p. 112).

Procedure. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the participants were contacted individually via social networks/email. The readers were unfamiliar with the poems; they received the original texts with the titles and the authors’ names, the questionnaire, discussion task, instructions, and explanations of the technical terms in English (see Appendices 1 and 3). The participants were to read each poem separately, mark its detected characteristics in the questionnaire, and orally discuss a poem. The readers worked at their own pace. Audio files were made, and the protocols were transcribed verbatim1.

The UA readers discussed the poems in English. They have good speaking skills; their vocabulary is extensive enough to express their thoughts/feelings. Asking them to use Ukrainian meant switching between the languages, which we tried to avoid.

Protocol analysis involved statistical analysis, comparison, and interpretation of the results obtained from the US/UA questionnaires (intertextual/infratextual context characteristics); comparative analysis of the US/UA readers’ oral answers (intratextual context dimension).

The TFA protocols were subjected to content analysis aimed at discovering how the readers used the imagery to construct appropriate text-worlds, their emotional reactions, and how they worked out the meaning of the poems.

3. Results

The results will be discussed in separate sections devoted to each of the characteristics investigated (intertextual, infratextual, intratextual).

3.1 Intertextual context characteristics

The intertextual characteristics were detected by the majority of the US/UA readers. (Figures in the tables stand for the number of participants who noticed a particular characteristic. N = 11.)

Table 3. Intertextual context characteristics as detected by participants when reading three poems

|

|

Poem 1 |

Poem 2 |

Poem 3 |

|||

|

|

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

|

Characteristics |

||||||

|

1.1 Reflecting social reality |

11 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

11 |

10 |

|

1.2 Metaphoric content |

9 |

11 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

6 |

The results of Fisher’s Exact Test for Count Data (with the use of the statistical programming language R) did not show a statistically significant difference between the answers of the US/UA participants concerning characteristics 1.1 and 1.2 in the totality of the three poems (1.1 p = 1; 1.2 p = 0.1813527) or each individual poem.

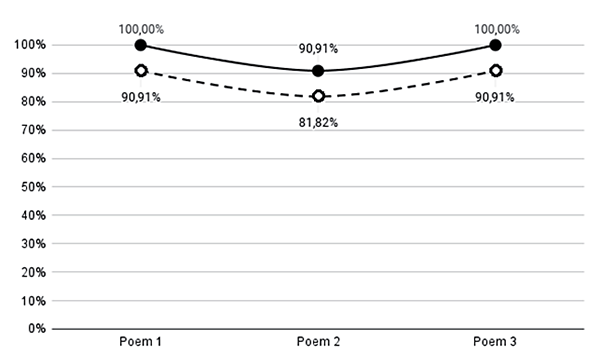

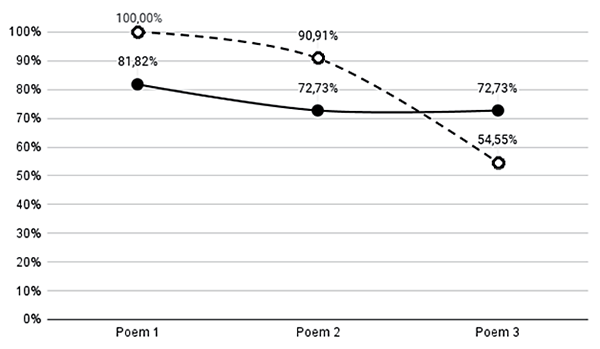

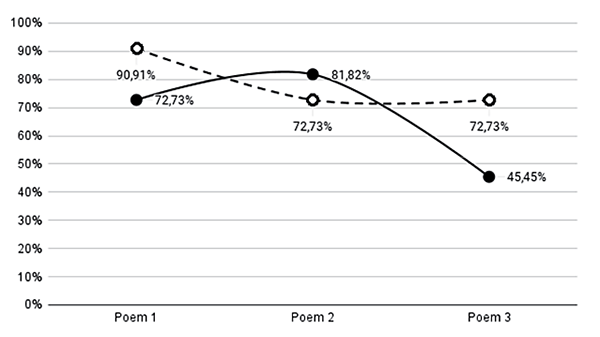

Figures 1 and 2 show the degree of value placed on these characteristics by:

● the US readers

o the UA readers

Fig. 1. 1.1 Reflecting social reality

Fig. 2. 1.2 Metaphoric content

Characteristic 1.1 Reflecting social reality is markedly pronounced in the three poems, which abound in references to real-world situations, social processes, and material objects; characteristic 1.2. Metaphoric content reflects the intrinsic property of poetry.

3.2 Infratextual context characteristics

The infratextual characteristics proved to be a contentious issue.

Table 4. Infratextual context characteristics as detected by participants when reading three poems

|

|

Poem 1 |

Poem 2 |

Poem 3 |

|||

|

|

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

|

Characteristics |

||||||

|

2.1 Initial part: indicating world-builders |

7 |

8 |

9 |

11 |

5 |

4 |

|

2.2 Intermediate part: telling the story |

6 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

8 |

|

2.3 Closing part: explicated/implicated conclusion |

8 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

8 |

Fisher’s Exact Test for Count Data (with the use of the statistical programming language R) showed no statistically significant difference between the views of the US/UA participants on characteristics 2.1–2.3 either in the totality of the three poems (2.1 p = 0.871398; 2.2 p = 0.2472811; 2.3 p = 0.7809002) or in each poem.

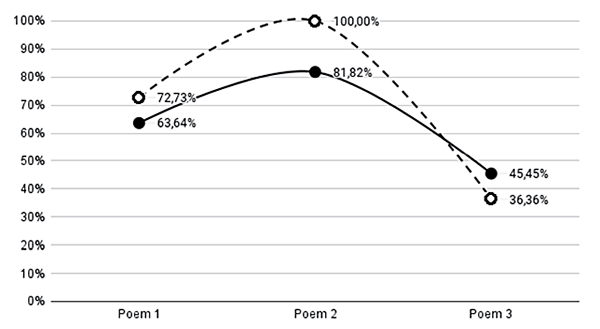

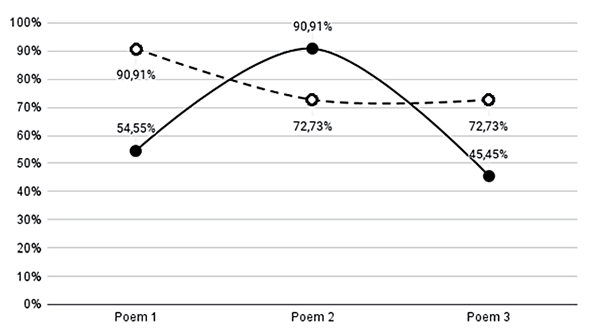

The participants’ views on the relevance of the infratextual context characteristics vary across the groups/poems (Figures 3–5):

● the US readers

o the UA readers

Fig. 3. 2.1 Initial part: indicating world-builders

Fig. 4. 2.2 Intermediate part: telling the story

Fig. 5. 2.3 Closing part: explicated/implicated conclusion

3.3 Intratextual context dimension

Imagery. According to Castiglione (2020), the proximity/distance factor correlates with the level of the image’s detail. In Poem 1, the enactor/focaliser is placed in close proximity to the object, the rock; hence very clear images, described by all the US/UA readers, who paid special attention to pushing your limits, struggle through to the top, arms on fire, car park, toilets, café. The same approach is true for Poem 2. The US readers spotted a variety of hospital/support imagery; the Ukrainians, mostly what they might take as metaphoric imagery, e.g. learn- / ing to walk, a stranger / helps a stranger, altar to life. All the readers agreed on the textual bases of the patient/hospital images. The Americans, collectively, highlighted the imagery in all stanzas in Poem 3; the Ukrainians, mostly extra day, letter, room; the majority of the US/UA protocols discussed imagery/images in relation to a specific stanza.

Text-worlds. The constructed text-worlds were the same: hard and frustrating climbing (Poem 1); hospital, patients who try to support one another (Poem 2); everyday life scenes, separate but similar in meaning (Poem 3). Some were ingenious: “[it] feels like a vault, a space that is quiet, place where the sun doesn’t necessarily shine” (US 9 about Poem 2)2; “I imagine the road, and the sun, and I can smell petroleum... it’s romantic and sad” (UA 8 about Poem 1); a narrative about a lonely woman that encompasses all text-worlds of Poem 3 (US 2; see Appendix 2). In Poem 3, the US readers discussed the text-worlds in all stanzas; seven out of eleven UA readers, those in the last two stanzas only.

Interpretations. The majority of all interpretations were metaphorical (Table 5).

Table 5. Metaphorical reception of three poems by study participants

|

Poems |

Metaphorical |

Examples |

||

|

|

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

|

Poem 1 |

9 |

11 |

Western society feels that you always have to stretch yourself sometimes to the limit, only to find basic comfort things. (US 3) |

The poem is about vanity and unnecessary struggles with the world, pride and illusions. (UA 2) |

|

Poem 2 |

8 |

10 |

Something that comes by surprise breaks the uniformity of what is expected. (US 6) |

Life is a circle, you can’t break a circle alone. (UA 2) |

|

Poem 3 |

8 |

6 |

Little moments of life, that’s where we can feel life’s generosity. (US 1) |

It’s about the ability to feel and understand the moments. (UA 6) |

A minor part of the US/UA readers said that a particular poem was “no poetry”, “not consistent”, and the ending destroyed the image; thus, we inferred that they had problems with its composition/style (Table 6).

Table 6. Difficulties encountered by participants when reading three poems

|

|

Poem 1 |

Poem 2 |

Poem 3 |

|||

|

|

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

US |

UA |

|

Number of readers who encountered difficulties |

1 |

– |

1 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

The overall emotional response to Poem 1 was a disappointment (seven US and seven UA readers); to Poem 2, empathy with the enactors/theme (eight US and ten UA readers). The US readers felt more positive about Poem 2. The emotional responses to Poem 3 varied: the Americans had a bittersweet feeling, felt grateful, optimistic, light-hearted, nostalgic, sad, tired, old, lonely, annoyed; the Ukrainians, pensive, sad, depressed, bored; three US and five UA readers said they had no emotional connection to a particular poem.

4. Discussion

4.1 Intertextual context dimension

Intertextual context characteristic 1.1 Reflecting social reality was detected by most US/UA readers (Figure 1). The protocols highlight the world-builders and function-advancing propositions in the poems’ text-worlds: “You see the cow, you see the spots that she talked about, you see the calendar, you see the drunk accidentally fall, you see a package returned back, a woman exchanging a scarf” (US 2 about Poem 3); “There has to be a toilet up there, a café to accommodate all these people who already got there” (UA 9 about Poem 1). For the Americans, 1.1 had the highest degree of relevance among other characteristics suggested in this study.

The US readers put social issues above the issue of metaphoricity and paid less attention than the Ukrainians to 1.2 Metaphoric content in the first two poems. However, they were more consistent in their views on Poem 3, where the UA readers’ marks dropped remarkably (Figure 2). Presumably, the Ukrainians hold a traditional view on poetry as intrinsically metaphoric; about half of them failed to get the metaphoric meaning behind the mundane text-worlds in Poem 3.

4.2 Infratextual context dimension

In some cases, certain regularities in the structure of poetic texts can be detected. Nevertheless, the US/UA reader’s opinions on the relevance of characteristics 2.1 Initial part: indicating world-builders; 2.2 Intermediate part: telling the story; 2.3 Closing part: explicated/implicated conclusion (Figures 3–5) show that the schema was challenged more often than not; apparently, the readers felt that the poems do not follow structural conventions.

4.3 Intratextual context dimension: interpretations of the poems

The US readers paid closer attention to the imagery than the Ukrainians; the latter focused mainly on what they presumably believed to be metaphoric imagery. However, all the TFA protocols show that the mental images were the same: a person struggling up a rock, a car park, toilets, a cafe; a hospital, people who suffer, help one another, and pray; a calendar, a door between lit and dark rooms, a letter, etc.

The text-worlds were also similar but differed in nuances within/across the groups. Occasionally, details added to a story gave text-worlds new world-builders and relational processes. The Americans offered a fuller coverage of the text-worlds in non-narrative Poem 3; the UA readers focused mainly on the last two stanzas, which they apparently believed to be truly metaphoric.

The protocols give us an idea of the readers’ processing modes. Both groups understood semi-narrative texts 1 and 2 better than non-narrative text 3. The protocols of the first two poems mostly reflect the original texts in the order of the information provided. In Poem 3, the readers tended to choose the bits that stood out and then added details from other parts of the text. This strategy (a) reflects the theory of linear assimilation of non-difficult poems vs. delinearized assimilation of obscure ones (Yaron, 2002, 2003); (b) is related to lack of narrativity as a factor in difficulty (Castiglione, 2019, pp. 152–154).

The poems were interpreted metaphorically by the majority in both groups; occasionally, a reader conjured a situation beyond the frame of the story and offered creative interpretation: “It [Poem 1] makes your body want to move, like you want to exert yourself” (US 11; LIFE IS MOVEMENT); “It [Poem 3] makes me feel like I feel in October. It’s still warm, but the wind is cold, and the nights are long, and you understand that darkness is very close already” (UA 8; LIFE IS A CHANGE OF SEASONS). The protocols of the US/UA readers in their 50s–70s confirm this tendency: “Life can be futile. We struggle and work hard, and in the end, things can just seem absurd” (US 12 about Poem 1; LIFE IS CLIMBING/DISAPPOINTMENT); “Is suffering a test? Read the Book of Job” (UA 13 about Poem 2; SUFFERING IS A TEST). This is in line with Joan Peskin’s (1998, p. 254) conclusion that novices may lack schemas for genres/forms, but are guided by expectations about metaphoricity.

The US/UA readers encountered the same difficulties. The texts feature conceptual metaphors (Castiglione, 2019, pp. 130–135) and overlapping tropes (Vengalienė, 2019) – metaphor/irony/simile. Some readers failed to grasp their metaphorical content; hence discrepancies between marking characteristic 1.2 in the Questionnaire (Appendix 3) and the interpretation of a poem. Some US/UA readers said that the poems aroused no emotion, were incoherent, confusing, or “no poetry” at all (Steiner’s (1978) tactical difficulty type).

The idea of coherence may be challenged by metaphors (a reader should “reinterpret these in relation to the context” (Svensson, 1987, p. 479)); by lack of narrativity, of “connectives … , by register mixing and shift of person, time, place reference” (Castiglione, 2019, p. 151, 152–154). We may conclude that lack of connectives and register mixing (narration split by free indirect discourse) are factors in difficulty in Poem 2; lack of narrativity and world-switches, in Poem 3.

Thus, similarities in the answers of the US/UA readers concern (a) the metaphoric imagery, (b) the text-worlds, (c) metaphorical interpretation (d) the difficulties. The explanation may be as follows. According to Peskin (1998, p. 237), for some poems, the number of possible interpretations may be “severely constrained by the text”. Poems 1 and 2 appear to belong to this type. Also, we may suggest that some poems create the same difficulties for different readers.

The US/UA interpretations differed because the US readers paid more attention to various imagery (Poems 2, 3) and world-switches (Poem 3). A possible explanation is that the UA readers traditionally believe that only the imagery/text-worlds that they can interpret metaphorically are worth their attention (e.g. build an altar to / life / out of air in Poem 2; the last two world-switches in Poem 3). The US readers’ emotions were more positive (Poems 2, 3), which may be caused by differences in national characters, but the matter requires a separate study.

Conclusion

Our initial hypothesis was that there would be more similarities than differences in the American/Ukrainian readers’ receptions of three contemporary free verse poems. In order to test it, we suggested sets of specific characteristics for the intertextual/infratextual/intratextual context dimensions outlined by Meibauer. Comparative analysis of the US/UA readers’ opinions shows that our hypothesis works for the intertextual and intratextual context dimensions but is ineffective for the infratextual one.

The intertextual context characteristics – reflecting social reality, metaphoric content – were perceived as relevant by the majority of both groups of readers.

TWT, developed by Werth and Gavins, is the underlying framework of intratextual analysis. The US/UA readers’ protocols (Eva-Wood’s TFA method) showed that most readers understood how important social/personal issues were brought into focus through particular text-world elements and that there was essential similarity concerning metaphoric imagery, text-worlds, metaphorical interpretations, difficulties in reception.

Our hypothesis that similarities in the readers’ receptions might prevail over differences was not confirmed for infratextual context dimension. Different opinions across the groups and the texts reflect the variability of structural forms most appropriate for the writers’ purposes. This result is possible since the infratextual dimension, being structural, is more complex to identify than themes or imagery, thus, more variation should be expected (especially given the structural freedom displayed by contemporary free verse as used in the study).

An essential agreement in the views of the US/UA readers may be explained by the fact that the poems’ text-worlds are, to an extent, culture-independent as they aim at general human themes. It also seems probable that certain types of difficulties may channel interpretations and diminish the role of culture.

We suggest that in the reception of the three poems, the factor of text-world content comes before the factor of culture. Is it likely that the reception of contemporary free verse, in general, is shaped more by text-worlds and themes than by readers’ cultural backgrounds due to globalization? The question is worth considering.

The limitations of the study are a comparatively small number of participants involved and heterogeneity across occupations. Further research on the balance between content and cultural factors in the reception of narrative/non-narrative poetry by particular groups of readers can give us a better understanding of the problem.

Sources

Hirshfield, J., 2012. February 29. Poets.org Poems. [online] Available at: <https://poets.org/poem/february-29> [Accessed 29 December 2020].

Howell, S., 2018. The long hall. In: S. Howell. I Left Nothing Inside on Purpose: Poems. [e-book] USA, Canada: McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company, p. 60. Available through: Google Books <https://books.google.com.ua/books?id=1IYqDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Stevie+Howell+I+left+nothing+inside+on+purpose&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Stevie%20Howell%20I%20left%20nothing%20inside%20on%20purpose&f=false> [Accessed 22 January 2021].

Swan, M., 2011. How everything is. In: M. Swan. The Shapes of Things. South Pool Nr Kingsbridge, Devon: Oversteps Books Ltd, p. 2.

References

Castiglione, D., 2017. Difficult poetry processing: Reading times and the narrativity hypothesis. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics, 26 (2), pp. 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947017704726.

Castiglione, D., 2019. Difficulty in poetry: A stylistic model. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castiglione, D., 2020. The stylistic construction of verbal imagery in poetry: Shooting distance and resolution in Wilfred Owen, Marianne Moore and Philip Larkin. In: J. Piątkowska and G. Zeldowicz, eds. Znaki czy nie znaki? Tom 3. Struktura i semantyka utworów lirycznych. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, pp. 43–79. https://doi.org/10.31338/uw.9788323543800.

Chesnokova, A., Zyngier, S., Viana, V., Jandre, J., Nero, S., 2009. Universal poe(try)? Reacting to “Annabel Lee” in English, Portuguese and Ukrainian. In: S. Zyngier, V. Viana and J. Jandre, eds. Linguagem, criatividade e ensino: abordagens empíricas e interdisciplinares. Rio de Janeiro: Publit, pp. 193–211. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3360.5442.

Chesnokova, A., Zyngier, S., Viana, V., Jandre, J., Rumbesht, A., Ribeiro, F., 2017. Cross-cultural reader response to original and translated poetry: An empirical study in four languages. Comparative Literature Studies, 54 (4), pp. 824–849. https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.54.4.0824.

Childs, P., Fowler, R., 2006. The Routledge dictionary of literary terms. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Eva-Wood, A. L., 2004. Thinking and feeling poetry: Exploring meanings aloud. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (1), pp. 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.182.

Gavins, J., 2007. Text world theory: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Gavins, J., Lahey, E., 2016. World building in discourse. In: J. Gavins and E. Lahey, eds. World building: Discourse in the mind. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1–13.

Hanauer, D., 1998. The genre-specific hypothesis of reading: Reading poetry and encyclopedic items. Poetics, 26 (2), pp. 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(98)00011-4.

Jakobson, R., 1960. Closing statement: Linguistics and poetics. In: T. A. Sebeok, ed. Style in Language. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press, pp. 350–377.

Kuzmičová, A., 2012. Fidelity without mimesis: Mental imagery from visual description. In: G. Currie, P. Kotátko and M. Pokorný, eds. Mimesis: Metaphysics, cognition, pragmatics. London: College Publications, pp. 273–315.

Kuzmičová, A., 2013. Mental imagery in the experience of literary narrative: Views from embodied cognition. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

Kuzmičová, A., 2014. Literary narrative and mental imagery: A view from embodied cognition. Style, 48 (3), pp. 275–293. Available through: JSTOR website <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.48.3.275> [Accessed 28 June 2022].

Mason, J., 2019. Intertextuality in practice. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Meibauer, J., 2012. What is a context?: Theoretical and empirical evidence. In: R. Finkbeiner, J. Meibauer and P. B. Schumacher, eds. What is a Context?: Linguistic Approaches and Challenges. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.196.04mei.

Peskin, J., 1998. Constructing meaning when reading poetry: An expert-novice study. Cognition and Instruction, 16 (3), pp. 235–263. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1603_1.

Peskin, J., 2007. The genre of poetry: Secondary school students’ conventional expectations and interpretive operations. English in Education, 41 (3), pp. 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-8845.2007.tb01162.x.

Peskin, J., Wells-Jopling, R., 2012. Fostering symbolic interpretation during adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33 (1), pp. 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.08.002.

Riffaterre, M., 1978. Semiotics of poetry. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Semino, E., 2014. Language and world creation in poems and other texts. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Steiner, G., 1978. On difficulty. In: G. Steiner. On difficulty and other essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 18–47.

Stockwell, P., 2009. Texture: A cognitive aesthetics of reading. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Stockwell, P., 2017. The language of Surrealism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Svensson, C., 1987. The construction of poetic meaning: A developmental study of symbolic and non-symbolic strategies in the interpretation of contemporary poetry. Poetics, 16 (6), pp. 471–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(87)90014-3.

Todorov, T., Berrong, R. M., 1976. The origin of genres. New Literary History. Readers and Spectators: Some Views and Reviews, 8 (1), pp. 159–170. http://doi.org/10.2307/468619.

Toolan, M., 2001 [1988]. Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Toolan, M., 2016. Making sense of narrative texts: Situation, repetition, and picturing in the reading of short stories. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Vengalienė, D., 2019. Patterns of ironic metaphors in Lithuanian politicized discourse. Respectus Philologicus, 35 (40), pp. 30–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2019.35.40.02. Available at: <https://www.journals.vu.lt/respectus-philologicus/article/view/12714/11391> [Accessed 18 September 2021].

Wales, K., 2014. A dictionary of stylistics. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Werth, P., 1999. Text worlds: Representing conceptual space in discourse. New York: Longman Education Inc.

Yaron, I., 2002. Processing of obscure poetic texts: Mechanisms of selection. Journal of Literary Semantics, 31 (2), pp. 133–170. https://doi.org/10.1515/jlse.2002.013.

Yaron, I., 2003. Mechanisms of combination in the processing of obscure poems. Journal of Literary Semantics, 32 (2), pp. 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1515/jlse.2003.009.

Zhang, Y., Lauer, G., 2015. How culture shapes the reading of fairy tales: A cross-cultural approach. Comparative Literature Studies, 52 (4), pp. 663–681.

https://doi.org/10.5325/complitstudies.52.4.0663.

Zhang, Y., 2022. Cross-cultural literary comprehension: Theoretical basis and empirical research. Interkulturelles Forum der deutsch-chinesischen Kommunikation, 2 (1), pp. 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/ifdck-2022-0005.

Appendix 1

How Everything Is

Michael Swan

Perhaps this is how everything is.

The scree steepens into rockface;

you work your way up ten or twelve pitches,

each worse than the one before,

the last a brutal overhang

with few holds, and those not good;

somehow, pushing your limits,

you struggle through to the top

with your arms on fire,

to find a car park, toilets and a café.

The long hall

Stevie Howell

We’re in the ward

where you don’t

rush. Shaky, learn-

ing to walk the line

again, midlife.

Someone’s one

good hand propels

a wheelchair along

a sigmoidal path.

what is this feeling

what is the name for

how did I get here

This quiet work,

counting slow

laps down & back

through the long

hall. A secular

prayer, mouthed

in a secular

chapel – an island

where a stranger

helps a stranger

build an altar to

life

out of air.

February 29

Jane Hirshfield

An extra day –

Like the painting’s fifth cow,

who looks out directly,

straight toward you,

from inside her black and white spots.

An extra day –

Accidental, surely:

the made calendar stumbling over the real

as a drunk trips over a threshold

too low to see.

An extra day –

With a second cup of black coffee.

A friendly but businesslike phone call.

A mailed-back package.

Some extra work, but not too much –

just one day’s worth, exactly.

An extra day –

Not unlike the space

between a door and its frame

when one room is lit and another is not,

and one changes into the other

as a woman exchanges a scarf.

An extra day –

Extraordinarily like any other.

And still

there is some generosity to it,

like a letter re-readable after its writer has died.

Appendix 2

Table 7. Excerpts from the US/UA readers’ protocols

|

US 2 |

UA 11 |

|

Poem 3 |

|

|

To me, this poem is about a girl that works on a farm, her spouse or loved one has left due to some reason and she finds herself looking out of a window and seeing her cows and everything. And, as the counter goes by, she drinks sometimes, and then she tripped. She wakes up every morning to appease with black coffee, she’s trying to do business and she’s tried to send this person a package but it’s returned and she doesn’t know why. Obviously, this person is expecting somebody but, eventually, it comes down to where she’s waited her whole life and then she passes away. |

I see a room, a door, this space between a door and its frame, and light shining through it. I see a calendar hanging on the wall, a cup of coffee on the table by the laptop because you have work to do. It is about lack of time, this constant yearning for some extra time or wishing to turn back time. |

Appendix 3

Instructions given to the participants

Sample of the questionnaire and task

Read Poem 1.

Read the section Technical terms; then read the Questionnaire and Task.

Reread the poem.

In the Questionnaire, mark characteristics 1.1–2.3 if you detect them in the text.

“Poetry is about the head and the heart” (Eva-Wood, 2004, p. 184). Give oral answers to questions 3.1–3.4: say what you think and feel.

Proceed to Poems 2 and 3.

Technical terms

imagery – words that bring certain images to you mind

metaphor – the use of words with concrete meaning for abstract notions; metaphor is figurative in meaning

metaphoric content – ≈ metaphoric meaning

text-world – a picture in your mind that reflects a story you read

world-builders – elements of the text that indicate the time/place of action, characters, objects

Questionnaire

1. general view:

1.1 the poem reflects social reality

1.2 the poem has metaphoric content

2. parts of the poems:

2.1 initial – indicates world-builders

2.2 intermediate – tells the story

2.3 closing – presents a conclusion, directly/indirectly

Task

3. speak on the issues:

3.1 imagery that stands out for you

3.2 pictures (text-worlds) the poem evokes in your mind

3.3 emotions evoked by the poem

3.4 what is the poem about?