Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2024/2, vol. 114, pp. 130–176 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2024.114.4

Dr. Arūnas Molis

Analyst at the Centre for Defence Analysis,

General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania

E-mail: arunas.molis@lka.lt

Sara Pastorello

MA graduate in International Relations

(MIREES program, University of Bologna),

trainee at European External Action Service

E-mail: pastorello.sara1234@gmail.com

Abstract. The paper explores state sovereignty by developing a systematic framework for categorising states based on their sovereignty status. At the heart of our analysis lies the distinction between sovereign states and satellite states – a distinction that has significant implications for global security, stability, and the balance of power. While sovereign states exercise full autonomy and control over their affairs, satellite states often find themselves in a subordinate position, heavily influenced or even dominated by external powers. A theoretical framework deconstructs the concept of sovereignty into four crucial elements: authority, legitimacy, independence, and territoriality, which provide a structured assessment of the level of sovereignty in a state and serve as the basis for our analysis. To illustrate the application of our framework, we adopt a case study approach focused on Belarus. As a nation situated at the crossroads of Eastern Europe with a history marked by geopolitical contestation and strategic manoeuvring, Belarus provides a compelling context for examining sovereignty dynamics. Through a systematic analysis of Belarus’ political, economic, and military landscape, we seek to assess its sovereignty status within the framework of our analysis. While the topic of Belarus’ sovereignty and integration within Russia has been extensively explored over the years, the innovative contribution of this paper lies in purposefully designed methodology for sovereignty assessment and the use of the latest empirical data while practically applying the model for the case of Belarus.

Keywords: Belarus, sovereignty, Russian satellite state, regional security, economic dependence, human rights, political pressure.

Santrauka. Straipsnyje nagrinėjami valstybių suvereniteto kausimai, siekiant sukurti sisteminį pagrindą tolesniam ir kitų valstybių skirstymui pagal jų suvereniteto lygį. Tyrimo tikslas – nubrėžti aiškią takoskyrą tarp suverenių, pusiau suverenių ir satelitinių valstybių. Tyrimo svarbą lemia ta aplinkybė, jog skirtingas suvereniteto lygmuo gali turėti didelę reikšmę pasauliniam saugumui, stabilumui ir galios pusiausvyrai tarptautinėje sistemoje. Šiame kontekste suvereniomis valstybėmis tyrime įvardijamos visiškai savarankiškos ir kontroliuojančios savo politinius sprendimus šalys, o satelitinėmis – tos, kurios de facto patiria didelę išorės jėgų įtaką. Teorinėje tyrimo dalyje suvereniteto sąvoka išskaidoma į keturis esminius struktūrinius elementus: valstybės valdymą, teisėtumą, nepriklausomybę ir teritorinį vientisumą. Siekiant iliustruoti ir patikrinti kuriamos suvereniteto vertinimo sistemos taikymo efektyvumą yra nagrinėjamas Baltarusijos atvejis. Baltarusija, kaip Rytų Europos kryžkelėje esanti valstybė, kurios istorija nusižymėta geopolitinėmis varžytuvėmis, yra tinkamas pavyzdys suvereniteto dinamikai nagrinėti. Sistemingai analizuojant Baltarusijos politinį, ekonominį ir karinį kontekstą, tyrime nuosekliai vertinamas šalies suvereniteto status quo. Nors Baltarusijos suvereniteto ir integracijos į Rusiją tema jau daugelį metų yra plačiai nagrinėjama, darbo naujumą lemia kuriama suvereniteto vertinimo metodika ir naujausių empirinių duomenų panaudojimas praktiškai taikant modelį Baltarusijos atvejo analizei.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Baltarusija, suverenitetas, Rusijos satelitinė valstybė, regioninis saugumas, ekonominė priklausomybė, žmogaus teisės, politinis spaudimas.

_______

Received: 31/10/2023. Accepted: 06/05/2024

Copyright © 2024 Arūnas Molis, Sara Pastorello. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

In the complex landscape of international relations, the evolving dynamics of global geopolitics have often brought into question the extent to which states truly retain their sovereignty, particularly in the face of geopolitical pressures and strategic alignments. Sovereignty, defined as the “supreme authority in a state,”1 is a very complex and debated concept in both political and legal discussions. Nevertheless, the Peace of Westphalia is often seen as the starting point of the modern system of equal, sovereign states. According to Aalberts,2 it conventionally represents a turning point in European history, establishing principles like state sovereignty, territoriality, and non-interference in the affairs of other states.3 Scholars like Jean Bodin transformed the concept into an institution that represents the foundation of the contemporary international system. Thus, according to Bodin, to be sovereign means to possess the authority to make laws without any interference or need for consent from external parties.4 To use Waltz’s words: “to say that a state is sovereign means that it decides for itself how it will cope with its internal and external problems.”5

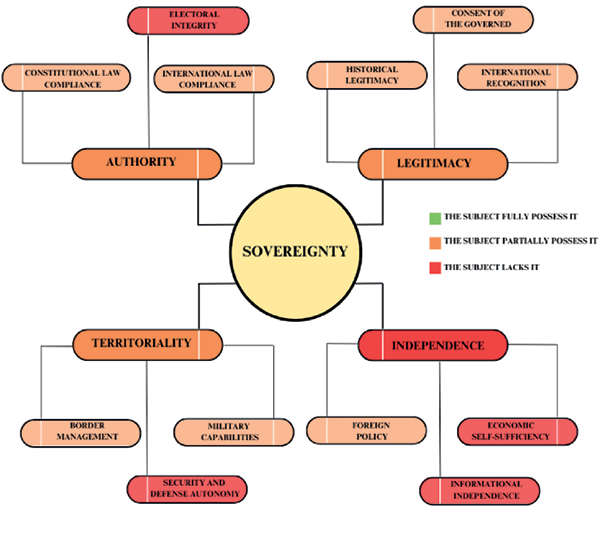

The current paper seeks to address this critical issue by developing a systematic framework for categorising states based on their sovereignty status. At the heart of our analysis lies the distinction between sovereign states and satellite (to be more precise – vassal) states, – a distinction that has significant implications for global security, stability, and the balance of power.6 While sovereign states exercise full autonomy and control over their affairs, satellite states often find themselves in a subordinate position, heavily influenced or even dominated by external powers. To develop our framework, we identify key indicators and criteria that constitute a modern sovereign state. We begin by discussing the definition of the modern conception of sovereignty: definition and key features are provided relying on such authors as E. N. Kurtulus and F. A. Vali. The analysis is followed by developing a model (for more details on the model, see Annex 1 at the end of the paper) that breaks down the concept of sovereignty into four crucial elements: authority, legitimacy, independence, and territoriality. This framework provides a structured assessment of the level of sovereignty in a state and serves as the basis for our analysis. Thus, the crucial task (which is also a key novelty and added value) of this paper is to build a model that allows to assess the level of autonomy and sovereignty in the modern world and test this model on a specific, very sensitive for the regional and global security case. This will first help to answer a question whether the level of countries’ possible dependency can be objectively measured at all. Secondly, while discussing the case of Belarus, it should become clear what problems arise in the practical application of the model.

The Republic of Belarus,7 a landlocked country in-between Russia and NATO’s allies, has often been overshadowed by its larger neighbour, and its sovereignty and geopolitical importance have been underestimated on the international scene. Unlike its Baltic neighbours, Belarus is a country that has never formally cut the “umbilical cord” that connects it to its “Mother Russia”8 and, therefore, while maintaining formal sovereignty, it has historically remained closely aligned with it. Numerous scholars have extensively explored the topic of Belarus’s sovereignty and its integration with Russia. For instance, Agnia Grigas’ characterization of their relationship as that of a “vassal and a master” provides a concise yet powerful descriptor of the dynamics at play between the two countries.9 This perspective underscores the long-standing influence of Russia over Belarus across various domains, ranging from economic and military spheres to the realm of soft power. Similarly, Pugačiauskas argues that the process began when the country signed the Belavezha Accords in 1991, entering the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and later the Union State Treaty in 1999.10 The enduring and asymmetric relationship has indeed spanned nearly three decades, with scholars such as Nizhnikau and Moshes highlighting the continuity of Belarus’ integration within Russia since its independence and identifting mechanisms and practices that Russia uses in its relationship with Belarus: the empirical contributions from political, security, economic and other domains suggest that the effect of Moscow’s pressure drastically reduced factual sovereignty (possibility of manoeuvring) of Belarus.11,12 The authors emphasise that this integration has been characterised by a strategic agreement wherein Minsk has traded its geopolitical loyalty and parts of its sovereignty in exchange for economic subsidies.13 So, according to Moshes and Nizhnikau, the crisis that started in 2020 is crucial, as Russia intentionally surpassed Belarus and – through a new model of relationship – forced the weak A. Lukashenko to give up any remains of independence of the state. Now the future of Belarus factually depends on Russia: its domestic issues, the outcome of the war in Ukraine, and Western-Russian relations.

On the other hand, many authors have also analysed Lukashenka’s efforts to distance himself from Putin’s influence. For instance, Matsukevich & Astapenia have emphasised the so-called “era of situational neutrality”, during which Lukashenka maintained a certain distance from Russia’s actions, seeking neutrality.14 This was evident in his non-recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008, as well as on his stance on the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Similarly, Kłysiński highlighted Lukashenka’s strategy of slowing down integration with Russia by balancing Moscow’s pressure with dialogue with the West. Therefore, the integration process of Belarus and Russia has been a prolonged and intricate journey, marked by different phases in their relationship. On the one hand, there have been periods where Belarus attempted to assert its independence to varying degrees, and on the other hand, the overall trajectory of Belarus-Russia relations has been explored and defined by several authors as one of enduring closeness. Additionally, the events of 2020/2021 have proven to be a turning point in Belarus’ foreign policy, leaving Lukashenka without space for a manoeuvre.

In other words, after nearly three decades of pulling back from integration, Belarus now stands at a juncture where the likelihood of any significant reverse shift in the integration process appears exceedingly slim. Indeed, the ongoing political crisis has prompted Lukashenka to turn once again to Russia, leading thus to what Stykow has defined as a “far-reaching loss of Belarus’ sovereignty”.15 Putin’s strategic influence over Belarus included pressuring it to host military installations, pursuing the implementation of the 1999 Union State Treaty,16 as well as using the Belarusian territory to attack Ukraine in February 2022.17 The latter action has been defined by Swierczek as “the final chord of Russia’s vassalization of Belarus,”18 asserting that Belarus has now essentially become a political buffer, maintaining only formal attributes of sovereignty.19

This view aligns with the analysis of many other experts. For instance, according to Ben Hodges of the Centre for European Policy Analysis, Belarus effectively lost its sovereignty following the disputed declaration of Lukashenka as the winner of the presidential election,20 while Gwendoline Sasse from Carnegie Europe accentuates the high cost of Lukashenka’s political survival, manifested in the compromise of Belarusian sovereignty vis-à-vis Russia.21 Likewise, Kamil Kłysiński, representing the Centre for Eastern Studies, observes an unprecedented surge in the importance of Russia for Belarus, leading to an exclusive and dominant alliance that renders Belarus’ sovereignty “de facto illusory.”22 For many authors, thus, the political survival of Lukashenka has come at the cost of ceding the nation’s independence, perpetuating its status as a political, economic, and military ally of Russia. However, while existing literature has predominantly focused on the integration of Belarus within Russia and the national implications stemming from it, internationally, Belarus remains a de jure sovereign state, relegating Belarus’ sovereignty, or rather the loss thereof, to the background amidst other pressing conflicts and geopolitical developments. Indeed, the loss of Belarus’ sovereignty is not solely pertinent in the context of potential threats to the country’s political autonomy, economic independence, and cultural identity but also encompasses broader implications.

Our methodology is based on a single case study logic and incorporates both qualitative and quantitative sources to provide a comprehensive assessment of sovereignty. We collect data from a variety of sources, including scholarly articles, government reports, and international databases. The data is analysed and synthesised to identify patterns, trends, and correlations relevant to our research questions. Notably, to ensure a nuanced understanding and enrich our analysis, between January and April 2023, we conducted semi-structured interviews with individuals knowledgeable about Belarusian affairs. These interviewees were selected based on their expertise in areas relevant to our research, spanning politics, economy and history (for the complete list of respondents, see Annex II). By engaging directly with these individuals, we gained insights and perspectives that complemented our quantitative analysis. In conclusion, the paper proposes methodology for sovereignty assessment and uses the latest empirical data for the practical application of the model in the case of Belarus. Successfully doing that would mean the model can be tested on other similar cases when disputes over losing or gaining more sovereignty in the field of international relations arise.

To analyse the extent of sovereignty in Belarus, it is first necessary to understand the specific nature of sovereignty itself. Scholars distinguish between de facto and de jure sovereignty. According to Kurtulus, the former refers to the ability – bestowed upon a state by law – to impose supreme authority within its territory and be independent of external interference,23 whereas the latter refers to the actual ability to impose such authority.24 Although factual non-sovereignty in a state is uncommon, there are four major categories of entities that, as Kurtulus outlines, belong to this spectrum: puppet states, satellite states, entities subject to imposed-unequal treaties, and coercively neutralised states.25 The concept of a satellite state – defined as an entity lacking factual state sovereignty while having a juridically sovereign status26 – is particularly intriguing when analysing a former soviet country like Belarus.

Although the meaning of “satellite state” depends on the geographical location of the person who uses it,27 the term has historically been associated with the states of Central and Eastern Europe that revolved around major powers, such as the Third Reich and later the Soviet Union. In this sense, satellite states – while outwardly maintaining independence and national sovereignty – are effectively in a state of political-ideological, economic, and military subordination, both domestically and internationally, as the result of military conquest, political alliance or economic agreements.28 Additionally, as underscored by Vali, these entities can undergo such control or dependence without receiving formal legal or official recognition of the actual state of dependency.29 In brief, while factual state non-sovereignty is rare, the provided definition of satellite state offers a valuable framework for analysing Belarus.

Given the definition of a satellite state, analysing sovereignty allows us to understand if Belarus fits the criteria typically linked with sovereign states or leans towards the classification of a satellite state. Besides the essential requirements outlined in the Montevideo Convention (1933), namely a permanent population; a defined territory; a government; and the capacity to enter into relations with other states,30 scholars have identified several additional features defining sovereignty: supreme authority, control, autonomy, external independence, internal supremacy, territoriality, and legitimacy.31 For instance, Philpott defines sovereignty as the “supreme authority within a territory,”32 indicating that a state is sovereign if it governs its own population, while being acknowledged by some other source of legitimacy. Similarly, Aalberts claims that sovereignty encompasses elements such as authority, power, autonomy, control, independence, and territoriality.33 While “territoriality” and “legitimacy” can be considered as integral aspects, the other features can be grouped into broader categories due to their interrelated nature. For example, the combination of supreme authority, internal supremacy, and control can be collectively labelled as “authority”, while external independence and autonomy can be combined under the term “independence”. Therefore, the four essential variables defining a sovereign state in this context are: authority, legitimacy, independence, and territoriality.

Authority is defined as “the power held by a political entity to require action and claim obedience to its rules”34 and is probably the most immediate feature of statehood. Although often used interchangeably with power, authority differs as it involves a dominant entity seeking voluntary compliance through rational persuasion and gentle manipulation, while power is often imposed through coercion.35 Authority also differs from control as it is usually associated with decision-making, while control with rule-enforcement.36 Nonetheless, according to Thomson, their “empirical relationship is of crucial importance in understanding and measuring sovereignty.”37 Authority possesses both an internal and external dimension, where the former refers to a state’s ability to exercise effective control over its territory and population, while the latter refers to a state’s ability to exert its authority in interactions with other states. Thus, to assess Lukashenka’s authority, both dimensions are considered through the evaluation of Belarus’ adherence to constitutional principles and compliance with international law.

Legitimacy represents the moral basis for authority, reflecting people’s respect and acceptance of it. Indeed, according to Beetham, leaders seek to justify their authority in a principle of legitimacy, to demonstrate their right to exercise their power and correspondingly be obeyed.38 Similarly, according to Weber, a state is legitimate when its leadership relies on the support of its population, who in turn agree that its rules or laws are just and worth obeying.39 Despite the sources of legitimacy having varied constantly throughout time, to include tradition, charisma, and legality, the major source of legitimacy are acts of consent.40 For instance, Rawls argues that a political entity is legitimate only if it exercises its power in accordance with a constitution41 while, according to Buchanan, to be legitimate, a political entity should respect the basic human rights of its subordinates, obtain power legally and adhere to international standards of behaviour.42 Therefore, evaluating Lukashenka’s legitimacy involves assessing popular support and his international recognition as the legitimate leader of Belarus.

Independence, intended as “the right of a state to manage all its affairs, whether external or internal, without interference from other states,”43 is the third feature of sovereignty. Under this understanding, the international community respects the sovereignty of individual states and refrains from interfering in their internal affairs. While in today’s globalised world, a fully independent state does not exist, the inability of a state to implement policies due to its dependence on another state represents a factor hindering its sovereignty. Therefore, of particular interest for our research is whether Belarus can be independent from other international actors or states, particularly Russia. To assess this, Belarus’ degree of independence, its ability to develop an independent foreign policy, to be economically self-sufficient and to be independent in its information sector, is analysed.

Territoriality, the last feature of sovereignty, has traditionally been defined as the ability of a political entity to demarcate and control a specific physical space.44 This ability involves defining and delineating borders that separates one state from another, as well as establishing sovereignty over the land within those borders.45 Nonetheless, the concept of territoriality, as we refer to here, goes beyond physical boundaries to encompass a state’s control over its population and the land it claims. In Sack’s words, “territoriality is not simply the circumscription of things in space <...>, it is circumscription with the intent to influence, affect or control.”46 For this purpose, boundaries become of extreme importance, as they entail territorial control, and hence, power prescribed over space and those within it. Assessing Belarus’s territoriality involves, thus, analysing its border management, its security and defence autonomy, and military capabilities.

Having established the theoretical framework for sovereign states, the next step is its application to the Belarusian case. The following analysis will determine whether Belarus still retains, to some degree, the above-mentioned key features, thereby confirming or denying its de facto sovereign status. Should Belarus fall short of meeting these criteria, we can draw conclusions about its status as either a sovereign or satellite state. To do so, the chapter is structured into four sections, each focusing on one of the four identified characteristics.

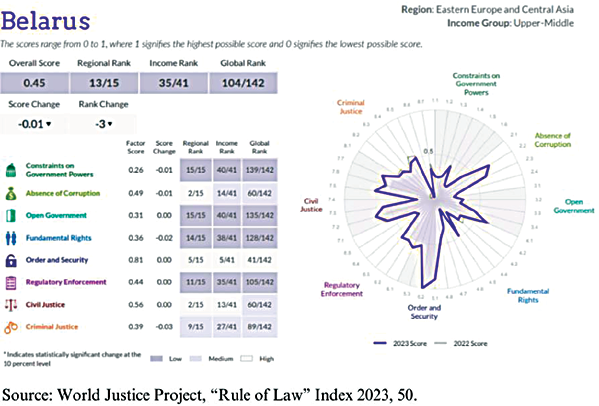

As mentioned before, authority refers to the ability of a government to exercise control over its population and in relations with other states. When analysing Belarus’ Constitution, Article 6 upholds that Belarus shall be bound by the principle of the rule of law. However, in WJP’s Rule of Law Index (2023) Belarus ranks poorly, especially when compared to other countries in the Eastern European and Central Asian region. This is evident from the graphic provided in Figure 1, indicating a significant gap in the country’s adherence to the rule of law. Indeed, with a score of only 0.45 on a scale from 0 to 1, Belarus ranks among the lowest in the region, highlighting the inability of its government to operate within legal boundaries.

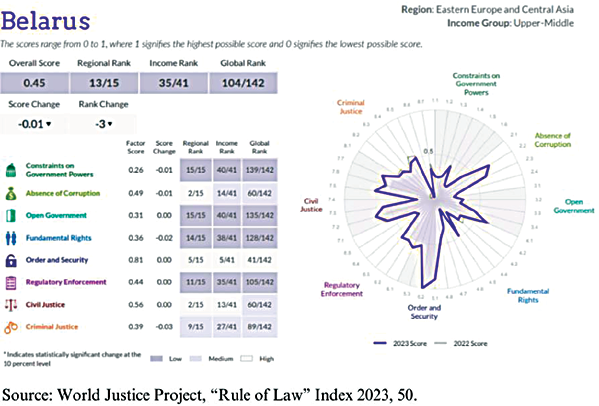

Of particular concern is the respect for fundamental rights which, as per Articles 2 and 21 of the Constitution, represent the state’s highest objective. In fact, especially after 2020, there has been an increase in the violations of rights such as freedom of thought and expression, with thousands being prosecuted and/or being labelled as “extremists.”47 Other rights violations were detected in relation to the electoral process, as Articles 38, 65, 66, and 67 of the Constitution, respectively, outline principles of universal suffrage, equality and free and direct participation. However, the 2020 elections faced multiple complaints regarding the intimidation, harassment and imprisonment of opposition candidates and their supporters.48 Lukashenka’s strategy for retaining power hinges on “the principle of perpetual incumbency, (which means that) the officially announced results are fabricated in order to create the narrative that the majority of the people support the current government.49 In other words, despite the constitutional provisions guaranteeing freedom of choice in the elections, the reality in Belarus often demonstrates that the electoral process is manipulated to favour a specific candidate. This is particularly evident in Figure 2, showing a glaring disparity between the official results released by Belarusian authorities50 and the reports provided by independent platforms like Golos, Zubr, and Honest People.51 According to the Central Election Committee (CEC), Lukashenka was declared the winner with 80.2 % of the vote. However, the independent platforms found proof of falsification at every third polling place, ultimately discovering that Tsikhanouskaya had won with 56%.52 This ongoing strategy is expected to persist and potentially further evolve leading up to the next presidential elections scheduled for 2025. Notably, this strategy has coincided with a decrease in political pluralism within the country. Indeed, the repression started in 2020 and the following mass emigration has resulted in a reduction in the presence of opposition parties, with those remaining being systematically targeted. In the most recent parliamentary elections held in February 2024, only the four pro-governmental parties were allowed to participate, a clear indication of the prevailing political landscape. Additionally, the most recent amendment in the Constitution, enacted in February 2022, plays a crucial role in undermining the de facto authority of Lukashenka. For instance, Article 80 states that presidential eligibility is restricted to individuals who have maintained residence in Belarus for a minimum of 20 years immediately before the elections, and who have not previously held citizenship, or a residence permit issued by a foreign state. This provision effectively disqualifies nearly all current oppositional candidates from running for the presidency. While the amendment directly weakens the opposition, it has also raised concerns about the impact on Lukashenka’s authority and the potential for increased influence from Moscow.53 Notably, Article 85 no longer confers the force of law upon presidential decrees, and Article 89 (1)(3) grants the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly (ABPA) substantial powers, including deciding on the domestic and foreign policy, on the military doctrine, as well as on the removal of the President from office. In this sense, the amendments to the Constitution, particularly those excluding certain candidates from participating in elections, represent a significant erosion of the regime’s de facto authority. As outlined in our theoretical framework, authority entails seeking voluntary compliance through rational persuasion and gentle manipulation. However, by enacting amendments that perpetuate incumbency and limit political competition, the regime under Lukashenka exhibits more coercive power rather than genuine authority. Therefore, these changes not only affect the legal framework but also have tangible implications for the regime’s authority and its ability to govern with legitimacy.

Belarus’ disregard for fundamental rights affects Lukashenka’s external authority as well. Despite being recognized as a sovereign entity by the international community and maintaining diplomatic, economic, and political relations with several countries, Belarus often violates its international obligations. For instance, the latest OHCHR report noted violations, including the arbitrary deprivation of life, torture, and violations of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association. Instances include the use of force during the 2020 protests, resulting in the unlawful deprivation of life of several Belarusian citizens54 and contravening Article 6 (1) of the ICCPR. Similarly, as per Article 7, no one shall be subjected to torture or to other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, yet the use of physical violence, such as kicking and beating, or the use of harmful substances such as chlorine55 against detainees, were reported. Another example of these violations concerns Article 9 (1), according to which no one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. However, a growing number of political prisoners is currently serving unfair sentences as a result of arbitrary detention and arrest, with more than 1383 detainees, as of 10 April 10 2024.56 Belarus also violated human rights in the treatment of migrants, enticing them to travel to the Belarus-EU borders under false pretences. According to Amnesty International, upon arrival, they were subjected to pushbacks by EU countries and experienced a series of abuses by Belarusian forces.57 Several reports highlighted cases of inhuman treatment, arbitrary detention, denial of access to asylum procedures, and the use of force by the Belarusian border guards. Belarus’ actions not only created tensions along the borders with Poland and Lithuania, but also infringed upon several other international provisions, such as Article 32(1) of the Refugee Convention, Article 13 of the ICCPR, Article 16(1) of the CAT, and Article 37(a) of the CRC. In turn, Belarus’ deliberate facilitation of migrant’s unlawful entry into EU countries, circumventing border controls, also interfered with the internal affairs of its neighbouring countries, consequently, violating the principle of non-intervention, outlined in article 2(4) of the UN Charter.

Belarus committed further international law violations by intentionally diverting Ryanair Flight FR4978 on 23 May 2021, to arrest opposition journalist Roman Pratasevich and his Russian girlfriend, Sofia Sapega.58 This act violated international provisions related to the safety of civil aviation, such as Article 4 of the Chicago Convention, which forbids the use of civil aviation for purposes inconsistent with those outlined in the Convention, and article 1 (1, e) of the Montréal Convention, which prohibits the dissemination of false information that endangers the safety of an aircraft in flight. Seizing an aircraft in flight endangered both the safety of individuals and property, infringing upon the Hague Convention as well. Last but not least, while Belarus denied any engagement in the harmful activities against Ukraine,59 allowing Russia to use its territory as a launchpad made Belarus the “enabler” of the war,60 breaching Article 16 (b) of the ILC’s Articles on the responsibility of states for Internationally Wrongful Acts and the following commentary,61 according to which permitting the use of one’s own territory by another state to carry out an armed attack against a third state constitutes a breach of international law.

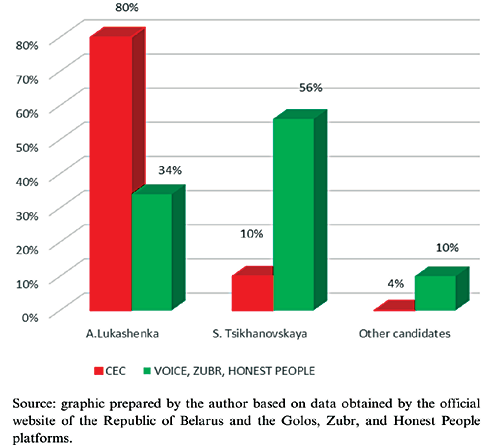

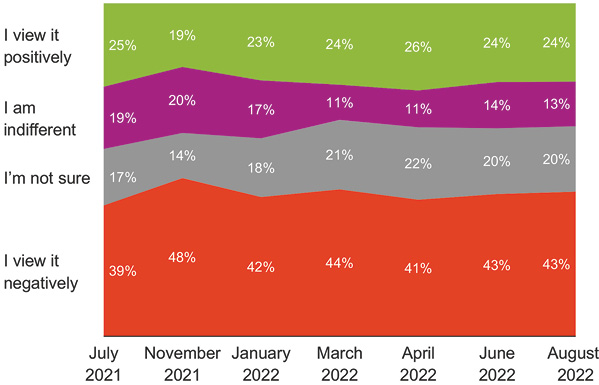

Legitimacy, both internally and externally, plays a crucial role in assessing Belarus’ status as a sovereign state. Internally, Lukashenka’s popular support has wavered throughout the years. While official Belarusian records claim that Lukashenka has held onto power since the birth of the Republic of Belarus,62 instances have arisen where elections did not accurately reflect the will of the population. Interviewee no. 3 emphasised that the 1994 election was “the only legal election ever since,”63 meaning that, despite the lack of concrete evidence until 2020, subsequent elections have often faced allegations of electoral fraud, resulting in extensive scrutiny, numerous protests, and international condemnation.64 Nonetheless, the 2020 elections and protests’ suppression marked a significant turning point in this regard, with growing disillusionment and scepticism towards the government. Indeed, the official outcome of the elections, coupled with evidence of fraud,65 had a profound impact on the social-political landscape of the country. Adding complexity, a series of consequential events, such as the weaponization of migrants,66 the Ryanair incident,67 the presence of Russian troops and the deployment of nuclear weapons in the country68 further fuelled scepticism and negative sentiments towards the authorities. Upon examining national polls conducted by Chatham House shortly after the 2020 elections, illustrated in Figure 3, it becomes evident that a significant majority expressed a severe distrust in Lukashenka and in the State institutions associated with his regime.

Similarly, the lack of support for the regime is also evident in the level of public acceptance of its decisions. For instance, in Figure 4, we can observe a generally unfavourable public attitude towards the establishment of Russian military bases and the deployment of nuclear weapons in the territory, with an average of 44% expressing a negative opinion.

Source: Chatham House (2022)

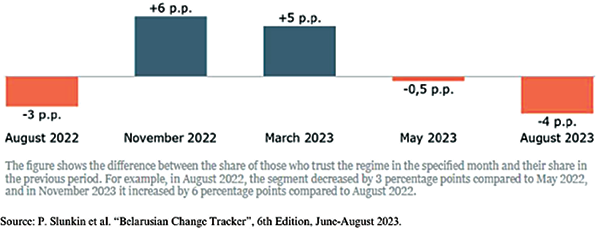

However, the 6th edition of the Belarusian Change tracker recorded fluctuations in these sentiments from August 2022 to August 2023, with an increase in the trust of the government until March 2023, and again a slight decrease from May to August 2023, as shown in Figure 5. Nevertheless, as reported by the authors, the last decrease is currently statistically insignificant to be considered as the beginning of a new downward trend.69

Therefore, due to the fluctuating trends witnessed from 2020 to the present, obtaining a definitive answer regarding the level of internal legitimacy becomes challenging. Bikinau’s “guide to sociology in Belarus’ dictatorships” offers valuable insights into comprehending the dynamics at play.70 Three key factors become crucial in determining the results of national polls: the highly unpopular war in Ukraine, which prompts Belarusians to prefer the current situation under Lukashenka over a potential future involving Belarus in the conflict;71 the emigration factor, as numerous regime opponents have left the country,72 and lastly, the pervasive influence of the fear factor, namely the respondents’ hesitance to answer certain political questions.73 This hesitance has only increased after the repression that the regime has been perpetuating since 2021.74 In this context, Bikinau asserts that the current upward trend is unlikely to persist, and contrarily to the pre-2020 situation, we can now observe a considerable number of individuals united in distrust of the regime and Lukashenka.75 Overall, despite the current upward trend, there is a noticeable decline in the level of trust in the government. While ongoing monitoring of these shifts remains imperative, it is possible to assert that Belarus has been experiencing a partial erosion of its internal legitimacy.

The 2020 elections impacted on Belarus’ external legitimacy, too. Indeed, despite a majority of actors have maintained a neutral stance concerning Lukashenka’s re-election,76 there has been a shift in Lukashenka’s recognition as the legitimate leader of Belarus. Of course, on the one hand, Russia and China have consistently shown their support for Lukashenka, enhancing his recognition as a legitimate leader. Russia, in particular, played a pivotal role in bolstering Lukashenka’s position by providing military, economic and propagandistic support.77 At Lukashenka’s request, Russia even established a “reserve police force” and deployed Russian journalists to operate Belarusian state TVs. However, this support has increased Belarus’ dependency and substantial debt to Russia, suggesting that Putin’s interest in Lukashenka’s recognition may be driven by the personal interest of keeping Belarus aligned, rather than a genuine recognition of Lukashenka as a legitimate leader.

On the other hand, while there have been attempts by Belarus and the Western countries to seek cooperation, the constant lack of respect for human rights and democratic procedures led the West to apply sanctions to Belarus, who in turn – isolated internationally – felt compelled to return to its Eastern partners. Although, as mentioned earlier, there was never an official lack of recognition towards Lukashenka, after the 2020 situation the U.S. and European nations refused to recognize Lukashenka as the legitimately elected president.78 Moreover, the U.S. issued an Executive Order (No. 14038) on August 9th, 2021, titled “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Belarus”, through which U.S. President Joe Biden condemned the “illicit and oppressive activities stemming from the August 9, 2020, fraudulent Belarusian presidential election and its aftermath,”79 demonstrating a lack of support for Lukashenka’s decisions and his authority in Belarus. Similarly, many European countries expressed disapproval towards Lukashenka and of his actions. Lithuania, for instance, was among the first countries to declare the non-recognition of the election results and of Lukashenka’s legitimacy as president.80 This sentiment was shared by many other European countries, including Denmark, Latvia, Germany, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, etc. For instance, the German government spokesperson mentioned that Lukashenka could not “evoke the democratic legitimacy that would have been the condition for him to be recognized as a legitimate president,”81 while the Slovak Foreign Minister directly claimed that “Lukashenka has no legitimacy to lead his country.”82 EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell also expressed concern in a declaration, claiming that Lukashenka’s secret inauguration in September 2020 “directly contradicts the will of large parts of the Belarusian population”83 and implementing six packages of sanctions in response.84 In short, while some countries maintain diplomatic ties with Belarus, the relative majority of actors do not consider Belarus’ regime as a legitimate authority. Indeed, by urging for accountability mechanisms and expressing their dissatisfaction with the undemocratic election procedures, the U.S., the European countries and the European Union sent a clear message that they believe Belarus lacks the democratic legitimacy required to govern the country, at least from a de facto point of view.

Independence, as highlighted in the theoretical chapter, refers to a state’s capacity to autonomously formulate and execute policies and decisions, free from undue external influence. Assessing Belarus’ independence primarily involves analysing its relationship with Russia, its closest ally and most deeply integrated partner. In terms of foreign policy, Belarus’ actions often deviated from its stated principles, aligning more closely with Russia’s objectives. For instance, Art. 23 and Art. 24 of the Law “On Approval of the Basic Directions of Domestic and Foreign Policy of the Republic of Belarus” respectively emphasise that Belarus’ foreign policy is founded on the adherence to universally recognized principles and norms of international law, a commitment to a policy of consistent demilitarisation of international relations, as well as the respect for the rights, freedoms, and legitimate interests of its citizens.85

However, as previously discussed, Belarus has frequently fallen short in adhering to international norms, while also abandoning its commitment to neutrality and demonstrating scarce abilities in upholding the rights and freedoms of its citizens. Consequently, the misalignment between Lukashenka’s foreign policy objectives and its practical actions plays a key role in weakening Belarus’s decision-making independence and allowing other actors to exert control. Among these actors, Russia is the main one. As aptly noted by Hansbury, the constant Western criticism of the human rights situation or the absence of fundamental freedoms propelled Belarus to close ties with Russia as a necessary shield for regime security.86 This process has only intensified after 2021 and, in fact, there has been increased alignment of political and social approaches seen in Belarus, mirroring those in Russia. This suggests potential influence or shared governance traits between the two nations. In particular, the 2020 elections provided an opportunity for Putin to coerce Belarus into supporting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and further align. Putin’s unilateral decision to place nuclear weapons in Belarus also played a pivotal role, sending “a very strong message to the whole world that Belarus is not independent.”87 To clarify, under ordinary circumstances involving two or more countries, diplomatic meetings and established protocols would precede the announcement of such a significant statement. This stands in contrast to the situation in Belarus, where Putin unilaterally declared the deployment of nuclear weapons in the country.88 As a result, if prior to this declarationthe West regarded Lukashenka as a decision-maker in the country, this event likely altered their perspectives. It underscored that the connection between Russia and Belarus does not represent a partnership between two independent nations but rather implies a substantial influence of one over the other. This constant integration is visible also from the two countries’ intention to facilitate the movement of their citizens across the shared border without passport or customs controls, as well as the continuous development of cultural, historical, and educational cooperation,89 which enhances the blurring of differences in the identity of Russian and Belarusian citizens, fostering common language and transforming Belarus into an effective extension of Russia.

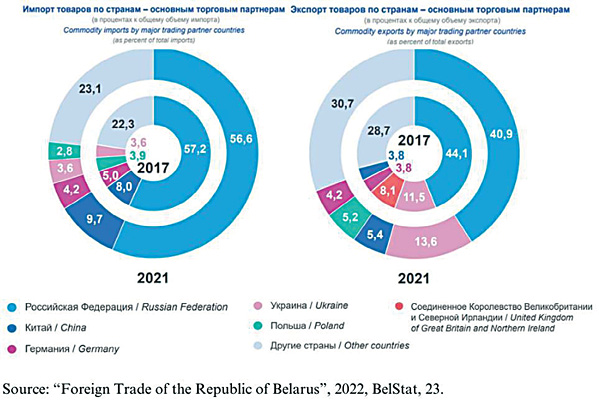

Regarding the economy, Belarus is an export-oriented country, ranking 72nd in the world in terms of GDP and 33rd out of 131 countries in the Economic Complexity Index,90, implementing a multi-vector foreign economic policy, and actively participating in international integration processes, such as the Union State and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).91 The original idea behind the creation of the Union State, as explored in depth by Deen, Roggeveen & Zweers, was to create an economic and political union of the two countries. However, the scepticism of Lukashenka over the past three decades has not led to any significant economic unification.92 On the contrary, the participation in the EAEU increased Minsk’s economic reliance on Russia, pushing Belarus into a spiral of economic dependency. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia has contributed to the economy of Belarus, both in terms of exports and imports, becoming Belarus’ main importer and general key trade partner. For instance, in 2021, Russia accounted for 49.0% of foreign trade in goods, 40.9 % of which was exports and 56.6 % of which was imports (as shown in Figure 6), whereas in 2022, Belarus became officially the most dependent country on Russia for trade, with a total turnover of imports and exports to and from the country equivalent to nearly half of the GDP.93 Energy subsidies from Russia provided critical support for the economy as well. Indeed, because of its modest natural resources,94 Belarus relies on imports from Russia to meet most of its energy needs. Thus, in addition to obtaining low-interest loans from Russia, the availability of cheap gas and oil has also played a significant role in the Belarusian economy, contributing to Belarus’s position as the first among the top-10 creditors to Russia in 2021.95 This dependency becomes even more evident as Russia uses Belarus’ mounting debt as leverage. In fact, the indirect involvement of Belarus in the Russian war against Ukraine cost Minsk most of its profitable export categories to the EU and led some investors to feel more sceptical and less attracted to the country, while allowing Russia to increase its influence in all sectors of the economy. Additionally, the pressure exerted by Moscow led Belarus to finally return to the economic decisions of the Union State and agree to implement 28 roadmap programmes, aimed at synchronising legislation, creating equal conditions for economic entities in both countries, and establishing a unified financial and energy market.96 In April 2023, the implementation rate of these programs was claimed to have reached almost 80%,97 further adding to the influence exerted by Russia on Belarus’ economy.

Belarus has historically maintained close ties with Russia in the realm of information and media as well. One primary factor contributing to this situation is that journalists in Belarus frequently encounter difficulties in expressing personal opinions or presenting content that deviates from the choices of the regime. It is not by chance that Belarus ranks 0/4 in the “Freedom in the World 2023” report and has been labelled as Europe’s “most dangerous country for journalists.”98 As outlined in Amnesty International’s 2022/23 report, numerous individuals have indeed faced legal action for expressing support for Ukraine, reporting on Russian troops movements, and criticising the government,99 while authorities have persisted in arbitrarily labelling organisations, online resources, printed materials, and other content as ”extremist.”100 The absence of media freedom, the escalating repression occurring since 2021, and the recent amendments to the 2008 Law “On Mass Media,”101 which broadens the grounds for blocking foreign and local news websites and aggregators, creates an environment where those providing information are compelled to align with the regime’s ideology. This, in turn, allows for Russian media and Russian propaganda messages to proliferate in Belarus, influencing and moulding the knowledge and perceptions of Belarusian citizens. Indeed, Russian television channels, radio stations, and printed newspapers, such as Komsomolskaya Pravda and Argumenty i Fakty, are widely accessible and consumed by the Belarusian population.102 The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) undertook an analysis of the main Belarusian television channels spanning from 2018 to 2020. The findings disclosed not only the greater influence of Russian television programs over their domestic counterparts but also identified recurrent instances of incorporating elements of pro-Russian and pro-integration propaganda, as depicted in Figure 7. In fact, numerous Russian media outlets or Belarusian platforms reproduce Russian information and endorse narratives akin to those outlined in Komsomolskaya Pravda and the Sputnik news agency, which are both linked to Russia and in 2018 resulted among the top 20 Belarusian media sites.103 Moreover, four out of nine regularly broadcasted TV channels in Belarus heavily rely on Russian TV production, airing over 60% of Russian-made TV programs.104 This mirroring has only worsened after 2022 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with Belarus copying and synchronising its state propaganda with Russian narratives, especially regarding the Ukrainian conflict. Some examples are that Russia’s actions against Ukraine are a necessary self-defence, and that the Russian army is liberating Ukrainian cities.105As of the current writing, these narratives persistently endure. Notably, Isans’ monthly review #3 of Belarus propaganda in December 2023 highlights influential messages emphasising the celebration of the “Union State” anniversary, Lukashenka’s positive image, of his international engagements and role as a mediator with Ukraine, as well as the deployment of Russian tactical nuclear weapons and anti-West, anti-Polish campaigns.106 Overall, the combination of a low degree of decision-making in foreign policy, the high level of dependence on economic subsidies, and the significant presence of Russia in the media and press landscape of Belarus are evidence of Belarus’s challenges in fully being independent from its ally, Russia.

Territoriality, as previously mentioned, refers to the ability of states to exercise control and authority over their defined territories, safeguarding them from external interference. The recent political events that occurred in Belarus raise concerns about the country’s ability to respect established borders and avoid unauthorised crossings. Although Belarus has not disputed territories, nor has violated the territorial integrity of another country by using military force, the Ryanair flight incident, the orchestrated migration crisis, and Belarus’ role in the Russian attack against Ukraine all had implications on border security. Indeed, while Belarus’ State Border Committee, responsible for interacting and cooperating with the border guard authorities of foreign countries, should have ensured the compliance with international treaties and prevent border incidents,107 Belarus’s actions exploited border management systems and protocols. In particular, the hijacking of the Ryanair flight by Belarusian authorities infringed upon the sovereignty of other states and undermined established principles of border management. Similarly, the deliberate encouragement of migrants to cross borders unlawfully undermined the principle of territorial integrity, challenging Belarus’ ability to respect established borders and once again contravening Belarus’s commitment to preventing border incidents. Lastly, while the Belarusian armed forces were not the instigators of the attack against Ukraine, the use of Belarusian territory for such actions raises concerns about Belarus’scapacity to exert complete control over its borders and prevent external actors from manipulating its territory for their political interests.

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|

US$ |

709.71 |

773.71 |

707.42 |

762.78 |

820.78 |

|

% of GDP |

1.2% |

1.2% |

1.2% |

1.1% |

1.2% |

Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, accessed on July 21, 2023.

Figure 9. Trend-Indicator Values expressed in millions of arms exports to Belarus, 2018–2022

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Total |

|

|

China |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Russia |

141 |

333 |

13 |

69 |

225 |

780 |

|

Total |

142 |

333 |

13 |

69 |

225 |

781 |

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, accessed on July 21, 2023.

In terms of security and defence, Belarus and Russia have always been strategic partners, establishing a joint regional military force, coordinating their air defence systems, and conducting joint military exercises. The increasing coordination makes Belarus exposed to Russia’s influence and limits its military independence. As visible in Figure 8, Belarus allocates only a small amount of rubles (1.2% of the GDP as of 2022) to national defence,108 which suggests that there may be certain dependencies or limitations regarding military capabilities and self-sufficiency. Furthermore, despite Belarus ranking amongst the top 25 arms exporters in 2022 according to SIPRI,109 the country’s domestic production does not fully meet its demands for weapons, thus lacking the capability to produce weapons and ammunition independently. This gap is filled by the Russian Federation which, as of 2022, supplies almost 100% of the weapons to Belarus, as indicated in Figure 9. It should be mentioned, though, that the last couple of years – just like it happened with the public opinion – have seen a reverse trend. Indeed, there has been a significant increase in military expenditure starting in 2022, potentially as part of Lukashenka’s election campaign pillar of “armed pacifism”. In other words, the Belarusian officials have acknowledged the need for preparation for potential involvement in the conflict, and as a result, the defence budget has increased by 40% in 2023 alone, with military training exercises ongoing and new units being formed, including special forces groups and people’s militia. Nonetheless, Belarus’ strategic capabilities remain relatively limited, with active military forces amounting only to 47, 950 soldiers.110 The Belarusian armed forces are also “constrained by underinvestment, low manning levels, and mostly Soviet-legacy hardware” and are strongly influenced by the Russian armed forces, which provide educational and training support. Indeed, as of February 2023, the only foreign forces present in the territory of Belarus were the Russian ones, exerting influence on the underdeveloped Belarusian armed forces. Significant in this regard was the latest decision of Lukashenka to welcome in Belarus the Russian group of “Wagner” mercenaries.111 Although their leader was confirmed dead in August 2023,112 this event has significant implications, from providing Lukashenka with a sense of notoriety to further solidifying Russian influence on the Belarusian military. Indeed, by sharing knowledge and expertise “about the weapons, <…> and how to attack, how to defend,”113 the Wagner group plays a crucial role in reinforcing Russian control over Belarusian military capabilities. Lastly, Belarus’s military doctrine is also coordinated with that of Russia, within the framework of the Union State. In November 2021, the Supreme State Council of the Union State approved a new military doctrine, focused on the pursuit of security and foreign policy, joint regional exercises, on deepening defence industry cooperation and combating hybrid threats.114 It was in this context that Belarus and Russia began the Allied Resolve joint exercises in 2022, further stepping up the military presence in Belarus. Additionally, in the latest months of 2022, Lukashenka announced the formation of Regional Group Forces (RGF)115 on Belarusian soil and the creation of a “common defence space” in the region, further enhancing the joint defence activities of the two countries and confirming the permanent stationing of the Russian troops on Belarusian soil.116

Overall, Belarus’s territoriality became void in the moment in which Russian troops used Belarusian territory to attack another country, demonstrating Lukashenka’s inability not only to safeguard its territory from external influences but also its inability to stop another country from exploiting its territory for their own political purposes. Of course, Russia has not implemented any tangible measures to administer or seize the country, as would be the case in an occupation scenario. Nonetheless, from a de facto point of view, Belarus’ situation is defined by interviewee no. 3 as a “creeping occupation.”117 meaning that although Belarus’ territory is not effectively under Russian military and administrative occupation, the increasing cooperation and interoperability of their air defence system and military personnel, the continuous joint exercises, as well as Belarus’ weak military capability are all signs of a lack of territoriality.

In conclusion, the intricate dynamics of sovereignty in the context of Belarus, particularly in its relationship with Russia, underscore the multifaceted nature of contemporary statehood and its far-reaching implications for global security and stability. Throughout this study, our primary objective has been to develop a systematic framework for analysing a country’s sovereign status. By scrutinising pivotal factors such as authority, legitimacy, independence, and territoriality, we aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of Belarus’ sovereign status, and its reverberations across the spectrum of international relations. Through our analysis, we have delineated a nuanced portrayal, indicating that Belarus exhibits characteristics consistent with Vali’s definition of a satellite state, rather than the archetype of a fully sovereign entity. Despite its ostensible de jure sovereignty, Belarus’ close alignment with Russia across political, economic, and military domains has gradually eroded its autonomy and self-determination.

Indeed, various factors such as economic dependency, political alignment, and military reliance have collectively contributed to the perception of Belarus as a satellite state, subject to considerable influence from its dominant neighbour:

• concerning authority, the regime’s consistent failure to comply with both domestic and international law has resulted in a lack of rule of law, the absence of a clear separation of powers, and only limited commitment to international obligations, which eroded the country’s authority on the international stage;

• on the legitimacy pillar, Lukashenka’s authority has been undermined by harsh crackdowns on dissent, the suppression of civil society, and a disregard for democratic principles. As a result, a significant portion of the Belarusian population has lost trust and confidence in his leadership;

• on the international stage, Belarus’s human rights violations have drawn condemnation from many democratic nations and the majority of countries refused to recognize Lukashenka as the legitimate leader of Belarus, hampering his ability to effectively engage with other actors on the global stage;

concerning independence, the analysis of Russia’s influence on Belarus’ foreign policy, economic and information landscape reveals that Belarus lacks autonomy and aligns its policies with Moscow’s. Territoriality analysis reveals Belarus’ inability to control its own borders, for instance, to prevent unauthorized crossings. Belarus’ military doctrine alignment with that of Russia further erodes Belarus’ control over its own territory, as it is being used for Russian military operations and attacks against Ukraine: inability to prevent other countries from exploiting its territory for their own political purposes signals about de facto absence of the complete territoriality. In conclusion, analysis demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed model and confirmed the initial claim that Belarus no longer fully meets the criteria required for a state to be considered truly sovereign. Indeed, although Belarus still maintains a juridically sovereign status on paper, it lacks factual state sovereignty and is controlled and/or has been made dependent on Russia without being incorporated yet. As a result, Belarus can no longer be considered as a sovereign state, but rather that it is becoming a full-fledged de facto satellite state of Russia. In other words, the nature of our approach has shed light on the intricate layers of Belarus’ unique geopolitical position, underscoring the imperative for policymakers, academics, and analysts to consider the implication of Belarus’ satellite state status when deliberating upon regional and global security strategies. Particularly, it proved, that amidst the current geopolitical climate – characterised by escalating tensions between democratic and authoritarian regimes – the significance of Belarus’ sovereign status cannot be overstated. Looking ahead, our research advocates the need for proactive initiatives aimed at addressing the legitimate security concerns emanating from Belarus, especially in light of Lukashenka’s recent political campaign, his emphasis on “armed pacifism” and the bolstering of military capabilities in the country.

Also, our study lays the groundwork for prospective research avenues and academic discussions in the realm of sovereignty dynamics. Future investigations could delve deeper into the evolving nature of satellite states in the contemporary geopolitical landscape, examining not only their interactions with dominant powers but also their internal dynamics and potential pathways toward greater autonomy. Comparative analysis could also shed light on the variations in satellite statehood across different regions, providing a clearer understanding on the factors that contribute to resilience or vulnerability in asserting sovereignty. Additionally, exploring the role of international organisations and mechanisms in mediating the relationship between satellite states and dominant powers also presents a promising avenue for research. Such exploration could yield valuable insights into strategies for reducing external influence and enhancing self-determination. Overall, the complexity and significance of satellite statehood underscore the need for continued scholarly engagement and empirical inquiry. By exploring these themes in greater depth, future research has the potential to inform policy making, foster international cooperation, and contribute to the advancement of theoretical frameworks in the study of state sovereignty.

References

Aalberts, Tania. Constructing Sovereignty Between Politics and Law. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Agnew, John. “The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory.” Review of International Political Economy 1, no. 1 (1994): 53–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4177090.

Amnesty International. International Report 2022/2023: The State of the World’s Human Rights. London: Amnesty International Ltd, 2023.

Amnesty International. “Belarus/EU: New evidence of brutal violence from Belarusian forces against asylum-seekers and migrants facing pushbacks from the EU.” December 20, 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/12/belarus-eu-new-evidence-of-brutal-violence-from-belarusian-forces-against-asylum-seekers-and-migrants-facing-pushbacks-from-the-eu/

Beetham, David. “Political Legitimacy.” In The Blackwell Companion to Political Sociology, edited by Kate Nash & Alan Scott, 107–117. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2001.

BelTa. “Лукашенко подтвердил участие Беларуси в СВО в Украине, но есть важные нюансы.” 4 October 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.belta.by/president/view/lukashenko-podtverdil-uchastie-belarusi-v-svo-v-ukraine-no-est-vazhnye-njuansy-527204-2022/

BelTa. “Лукашенко подтвердил приезд главы ЧВК «Вагнер» Пригожина в Беларусь.” 27 June 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.belta.by/president/view/lukashenko-podtverdil-priezd-glavy-chvk-vagner-prigozhina-v-belarus-574036-2023/

Bodin, James and Julian Franklin. On Sovereignty: Four Chapters from the Six Books of the Commonwealth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511802812

Z. Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. Basic Books, 1997.

Buchanan, Allan. “Political Legitimacy and Democracy.” In Ethics 112, no. 4, 689–719. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/340313

Camut, Nicolas. “Wagner Chief Prigozhin is in Belarus, Lukashenko says.” POLITICO. June 27, 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/wagner-boss-prigozhin-is-in belarus-official/

“Convention on the Rights and Duties of States. Conclusion date: 26 December 1933.” United Nations Treaty Series Online. https://treaties.un.org/pages/showdetails.aspx?objid=0800000280166aef

Dempsey, Judy. “Is Belarus’ Sovereignty Over?”. Carnegie Europe. 24 February 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/86512

Hanchuk, Pavel. “Inside the ‘Bear Hug’: Fostering Resilience in the Belarusian and Ukrainian Security Sectors.” German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep30237

Hackett, James, “The Military Balance 2023.” Abingdon: Routledge Journals, an imprint of Taylor & Francis, 2023. https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance/

Henderson, A. M. and Talcott Parsons. Max Weber: The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Free Press, 1964.

Herman, Martin Bille. In “United Nations Stands with People of Ukraine, Secretary-General tells General Assembly, Stressing “Enough is Enough, Fighting Must Stop, as Emergency Session Gets Under Way.” UN Press. 28 February 2022. https://press.un.org/en/2022/ga12404.doc.htm

Heywood, Andrew. POLITICS, 4th Ed. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013.

ICAO Secretariat. “Event Involving Ryanair Flight FR4978 in Belarus Airspace on 23 May 2021.” July 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.icao.int/Security/Pages/FFIT.aspx

Jačauskas, Ignas and Bns. “Lithuanian Parliament Declares Lukashenko Not Legitimate Leader of Belarus.” Lrt.Lt. 18 August 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1214304/lithuanian-parliament-declares-lukashenko-not-legitimate-leader-of-belarus

Коммерсантъ. “$1,7 млрд санкций и 4600 уголовных дел.” August 8, 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4935608

Kurtulus, Ersun N. State Sovereignty: Concept, Phenomenon, and Ramifications. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403977083

Lawrence, Thomas Joseph. The Principles of International Law. London: Macmillan & Co, 1927.

Liubakova, Hanna. “Belarus dictator prepares to extend reign via farcical referendum.” Atlantic Council. 11 January 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/belarusalert/belarus-dictator-prepares-to-extend-reign-via-farcical-referendum/

Martin, Elizabeth. Oxford Dictionary of Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. “Belarus and Russia.” Accessed 10 October 2023. https://mfa.gov.by/en/bilateral/russia/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. “Foreign trade. General information: directions, tasks, and results.” Accessed 10 October 2023. https://mfa.gov.by/en/export/foreign_trade/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. “Principles, goals and objectives of the foreign policy of the Republic of Belarus.” Accessed 10 October 2023. https://mfa.gov.by/en/foreign_policy/aims/

“Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, December, the 23rd 1933.” United Nations Treaty Collection. Accessed 03 October 2023. https://treaties.un.org/pages/showdetails.aspx?objid=0800000280166aef

Настоящее Время. “Путин косвенно подтвердил смерть Пригожина и назвал его «талантливым человеком сложной судьбы».” August 21, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2023. Путин косвенно подтвердил смерть Пригожина и назвал его «талантливым человеком сложной судьбы» (currenttime.tv)

Nizhnikau, Ryhor and Arkady Moshes. “Belarus in search of a new foreign policy: why is it so difficult?” Finnish Institute of International Affairs. 27 November 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. Belarus in search of a new foreign policy: Why it is so difficult | FIIA – Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

Nizhnikau, Ryhor and Arkady Moshes. Russian Policy towards Belarus after 2020: At a Turning Point? Lexington Books, 2023.

OEC World. “Economic Complexity Index (ECI) Rankings.” Accessed 10 October 2023. https://oec.world/en/rankings/eci/hs6/hs96

OHCHR. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Belarus, Anais Marin.” A/HRC/47/49. Human Rights Council. May 4, 2021. Fourty-seventh session 21 June – 9 July 2021. Agenda item 4. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ahrc4749-report-special-rapporteur-situation-human-rights-belarus-anais

OHCHR. “Belarus in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election and in its aftermath – Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.” A/HRC/49/71. Human Rights Council. March 4, 2022. Forty-ninth session 28 February–1 April 2022. Agenda item 4. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/regular-sessions/session49/list-reports

Official Website of the Republic of Belarus. “Presidential election 2020 in Belarus.” 14 August 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.belarus.by/en/press-center/belarus-presidential-election-news/belarus-presidential-election-results-finalized_i_0000117525.html

Philpott, Daniel. “Sovereignty.” In Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward Zalta. Fall 2020 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sovereignty/#DefiSove

RFE/RL’S Belarus Service. “U.S., Europeans Say Belarusian Leader Illegitimate as New Crackdown Follows Surprise Swearing-In.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 24 September 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.rferl.org/a/lukashenka-abruptly-sworn-in-for-new-term-as-belarusian-president/30853536.html

RFE/RL’s Russian Service. “Putin Says Transfer of Tactical Nuclear Weapons to Belarus Will Start Next Month.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 June 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-tactical-nuclear-belarus/32452500.html

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice: Original Edition. Harvard University Press, 1971. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9z6v

RSF. “2023 World Press Freedom Index – journalism threatened by fake content industry.” 3 May 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://rsf.org/en/2023-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-threatened-fake-content-industry

Sack, Robert L. “Human Territoriality: A Theory.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 73, no. 1 (1983): 55–74. London: Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1983.tb01396.x

Searing, Donald D. “The Psychology of Political Authority: A Causal Mechanism of Political Learning through Persuasion and Manipulation.” Political Psychology 16, no. 4 (1995): 677–696. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791886

SIPRI. “TIV of Arms Exports to Belarus, 2018–2022.”

State Border Committee of the Republic of Belarus. “Main tasks and functions of the State Border Committee.” Accessed October 10, 2023. https://gpk.gov.by/en/gpk/main-tasks-and-functions/

Stykow, Petra. “Making Sense of a Surprise: Perspectives on the 2020 ‘Belarusian Revolution’.” Nationalities Papers 51, no. 4: 803–822. Cambridge University Press, July 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.93

Swierczek, Marek. “Post-election Protests in Belarus as a Tool of Political Technology. Working hypothesis”. INTERNAL SECURITY REVIEW no. 27 (14) 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4467/20801335PBW.22.057.16948

TASS. “Belarus ratifies protocol to agreement with Russia on regional group of forces.” 29 June 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://tass.com/world/1640111

TASS. “Russia to extend $1.5 bln loan to Belarus.” 14 September 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://tass.com/economy/1200561

Terilkowski, Dyner. “The Belarusian Vector of the Russian threat to NATO.” The Polish Institute of International Affairs. 10 July 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://pism.pl/publications/the-belarusian-vector-of-the-russian-threat-to-nato

The White House. “Executive Order on Blocking Property and Additional Person Contributing to the Situation in Belarus.” 9 August 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/08/09/executive-order-on-blocking-property-of-additional-persons-contributing-to-the-situation-in-belarus/

Thomson, Janice E. “State Sovereignty in International Relations: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Empirical Research.” International Studies Quarterly 39, no. 2: 213–233. June 1, 1995. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2600847

TVP World. “Lukashenka and Putin agree on Belarus-Russia integration roadmaps.” 12 September 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://tvpworld.com/55793475/lukashenka-and-putin-agree-on-belarusrussia-integration-roadmaps

Viasna. “Political Prisoners in Belarus.” Accessed 10 October 2023. https://prisoners.spring96.org/en

Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1979.

Wesolowsky, Tony. “Elections in Belarus: How Lukashenka Won And Won And Won And Won And Won.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-lukashenka-referendum-russia/31725421.html

Wezeman, Pieter D., Justine Gadon, and Siemon T. Wezeman. “Trends in International Arms Transfer.” SIPRI. Stockholm: SIPRI. March 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://doi.org/10.55163/CPNS8443

I – Structure of the paper: The scheme created by the author, represents the deconstruction of the concept of sovereignty, first in its four main features and then again into each of the three most important aspects characterising each feature.

II - Interviewees data

|

Interviewee name |

Sector |

Role and Name of |

Venue |

|

Academic Research |

Research Fellow in the Department of History at Vytautas Magnus University (Kaunas) |

In person |

|

|

II: Olga Karach |

NGO |

Human rights defender, Head of the International Centre for Civil Initiatives and Human Rights Organization “Our House” |

Online |

|

III: Dzianis Kuchynski |

Governance |

Diplomatic Advisor to the president-elect Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya |

In person |

|

IV: Aušrinė Armonaitė |

Governance |

Minister of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania |

E-mail correspondence |

|

V: Robert Van Voren |

Academic research/ NGO |

Lecturer in Soviet/Post-Soviet Studies in Lithuania and Poland, Head of the Andrei Sakharov Research Centre for Democratic Development, and Head of the NGO “Federation Global Initiative on Psychiatry” |

In person |

|

VI: Valery Karbalevich |

Academic research |

Political analyst and lecturer at the Belarusian State University. Political columnist for Radio Liberty and commentator for Radio Liberty and Free News |

Online |

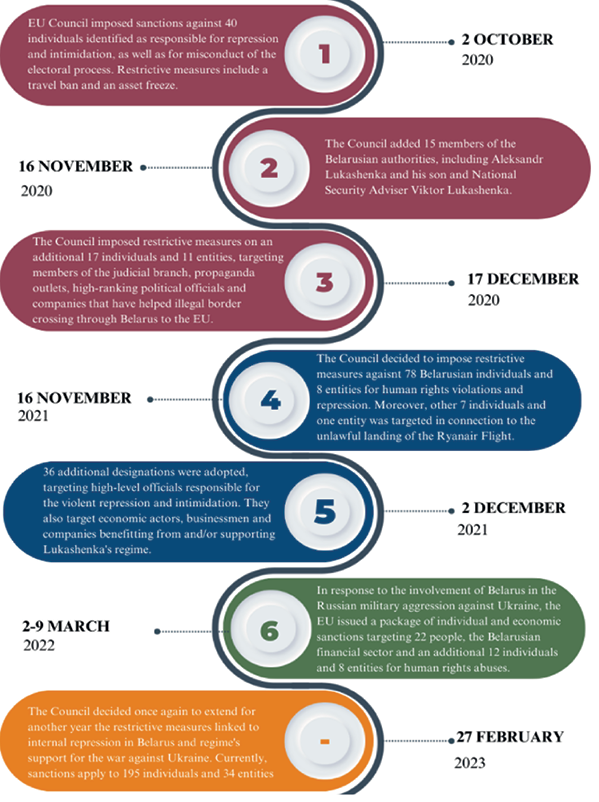

III - Timeline of the EU’s restrictive measures against Belarus (as of February 2023)

Source: Infographic created by the author based on data provided by the European Council (2023). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against-belarus/belarus-timeline/

IV - List of Abbreviations

• CAT - Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

• CEC - Central Election Committee

• CRC - Convention on the Rights of the Child

• EU – European Union

• GDP – Gross Domestic Product

• ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization

• ICCPR – International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

• ILC – International Law Commission

• NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization

• OHCHR – Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

• UN – United Nations

• WJP – World’s Justice Project