Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 1(27), pp. 133–151 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.85

The Effects of Brand Hypocrisy on Consumer Evaluations and Behaviors: Moderating Role of Nutrition Consciousness

Fuat Erol

Karamanoglu Mehmetbey University, Turkey

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0923-380X

ferol@kmu.edu.tr

--------------------------------------------------------

A previous version of this research was virtually presented at the 25th Marketing Congress held in Turkey from June 30th to July 2nd, 2021.

--------------------------------------------------------

Abstract. Many individuals accuse brands of hypocrisy for lacking transparency and sincerity, which could harm the brands’ image and lead to negative evaluations. Accusations of hypocrisy can also result in negative behavioral outcomes, such as brand distance and negative word of mouth (nWOM). This is particularly true for food brands, as it depends on individuals’ nutrition consciousness. Therefore, this study aims to explore the serial mediating effect of brand image and brand evaluations of the effect of the brand (mission) hypocrisy on both brand distance and nWOM, and the moderating role of nutrition consciousness on these indirect effects. Data was collected from 463 Turkish participants, and moderated serial mediation analyses were performed to test the research hypotheses. As a result, brand hypocrisy has a direct effect on brand evaluations, brand distance, and nWOM; nutrition consciousness has a moderating role on the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand image, and finally, brand image and brand evaluations serially mediate the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand distance and nWOM, where nutrition consciousness moderates both indirect effects. Thus, the current study theoretically and empirically advances the limited literature on brand hypocrisy and nutrition consciousness, and focuses on the assessment process of individuals and its behavioral outcomes.

Keywords: brand hypocrisy, brand image, brand evaluations, brand distance, negative word of mouth, nutrition consciousness

Received: 5/12/2022. Accepted: 27/2/2023

Copyright © 2023 Fuat Erol. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Since many consumers have become more suspicious of brands, they critically examine brands’ statements and behaviors (Guèvremont, 2019). One of the main reasons for this situation is that most individuals do not find many brands transparent or sincere enough (Maehle et al., 2011; Portal et al., 2019) and think that there are inconsistencies between their words and actions (Wagner et al., 2009). This can lead to a perception of hypocrisy (Zhigang & Haoming, 2020). Evaluating brands as hypocritical mainly leads to negative perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors towards them (Zhigang et al., 2020). Recently, brands such as McDonald’s, Volkswagen, and H&M have suffered negative consequences due to the perception of hypocrisy (Arli et al., 2019; Jung et al., 2021; Stender et al., 2006).

The concept of hypocrisy has attracted the attention of many researchers from both fields of business and marketing. However, most research has a similar scope and approach, where hypocrisy is investigated at the corporate level (Guèvremont, 2019). To truly understand perceptions and attitudes of individuals, it would be more accurate to evaluate hypocrisy in the context of the brand (Keller, 1993). Examining the relationship between brand hypocrisy and individuals in this context can provide a deeper understanding of the impact of hypocrisy. Besides, little is known about the behavioral outcomes of brand hypocrisy yet (Hur & Kim, 2020). Although brand hypocrisy is expected to lead to negative behavioral outcomes (Wagner et al., 2020), identifying alternative behaviors of individuals will provide new insights into the possible consequences of the hypocrisy perception. In this context, Weiner’s (1980) attribution-emotion-action model explains that individuals may reveal passive and proactive behavioral outcomes, respectively, in the form of avoidance or punishment in response to negative situations such as brand hypocrisy. Additionally, while many studies examine the direct consequences of hypocrisy, it is important to also investigate its indirect effects in order to gain a deeper understanding of how individuals make decisions (Zhigang & Haoming, 2020). The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) posits that individuals form attitudes based on their perceptions, which then influence their behavioral outcomes. Thus, examining the impact of brand-related perceptions and attitudes on behavioral outcomes is crucial for understanding the consumer-brand relationship. Previous studies have established a strong link between brand image and perceptions of the brand (Aaker, 1991; Faircloth et al., 2001; Keller, 1998) as well as between evaluations of the brand and attitude (Assiouras et al., 2013; Dawar & Pillutla, 2000; Lei et al., 2012; Low & Lamb, 2000). Therefore, it is beneficial to investigate the serial mediating role of these structures in the relationship between brand hypocrisy and behavioral outcomes. Finally, as people become increasingly conscious of health-related issues (Hwang & Cranage, 2010), and food brands are increasingly facing accusations of brand hypocrisy (Guèvremont, 2019; Stender et al., 2006), it would be beneficial to investigate the relationship between brand hypocrisy and nutrition consciousness. This is because an individual’s level of nutrition consciousness is likely to influence their relationship with food brands that they perceive as hypocritical (Aboulnasr & Sivaraman, 2010; Bower et al., 2003; Lockie et al., 2002; Mai & Hoffmann, 2012;). Thus, the current study aims to investigate the serial mediating effect of brand image and brand evaluations on the relationship between brand hypocrisy and brand distance and nWOM, as well as the moderating effect of nutrition consciousness on these indirect relationships.

This research makes several important contributions to the hypocrisy literature. First, by examining hypocrisy at the brand level, it will provide a better understanding of individuals’ perceptions and decisions (Keller, 1993). Second, by focusing on both passive (brand distance) and proactive (nWOM) behavioral outcomes, it will enhance the knowledge about the results of brand hypocrisy (Grégoire et al., 2009). Third, investigating the mechanism that explains the process between brand hypocrisy and behavioral outcomes will provide insight into the roles of brand-oriented associations, such as brand image and brand evaluations, in the relevant assessment process. Finally, this research is one of the first to explore the role of nutrition consciousness and the effect of brand hypocrisy on behavioral outcomes. The findings will clarify how individuals with different levels of nutrition consciousness differ in their perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors in the face of brand hypocrisy (Lee et al., 2014). Hereby, while the majority of previous studies considered that healthy nutrition issues are a concern of developed regions such as Europe and America (Iqbal et al., 2021), this study presents an alternative perspective from a developing country (i. e., Turkey). Results of the study will not only contribute to the improvement of the theoretical background for brand hypocrisy but also provide substantial managerial clues for practitioners, particularly those operating in the food sector.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Effects of Brand Hypocrisy on Individuals’ Assessment Process and Behavioral Outcomes

It is well known that brand crises can cause massive damage to firms (Dutta & Pullig, 2011). Previous studies have revealed that crises resulting from the violation of ethical values cause more negative results for brands than crises resulting from offering defective and unsafe products (Baghi & Gabrielli, 2019; Grégoire et al., 2010; Kübler et al., 2019; Trump, 2014). This reflects the importance that consumers place on issues such as honesty, transparency, sincerity, and ethics in their relationships with a brand (Maehle et al., 2011; Portal et al., 2019).

The increasing transparency and ethical practice expectations may cause some brand behaviors to be considered as “hypocrisy” by consumers, even though these behaviors do not violate regulations or cause a crisis. In this context, hypocrisy refers to negative perceptions attributed by consumers as a result of contradictions between stated business ethics and actual business practices (Wagner et al., 2009). In other words, hypocrisy is a dissimulation of one’s true nature or goals (Shklar, 1984). The concept of hypocrisy has been examined in the business and marketing literature through the lens of corporate hypocrisy, with a focus on corporate social responsibility (Arli et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2009; Zhigang & Haoming, 2020). However, the hypocrisy can be attributed to both corporations and brands as long as consumers believe that they claim to be something that they are not (Arli et al., 2019). Besides, based on the well-known importance of brand-level information on individuals’ decisions about the brands (Keller, 1993), addressing hypocrisy through brand-specific understanding is vital in understanding the evaluations and reactions of consumers. The concept of ‘brand hypocrisy’ could be defined as “the deliberate creation of an incorrect or unrealistic image by brands, thus imitating and/or manipulating features, motivations or beliefs” (Guèvremont, 2019, p. 599). While brand hypocrisy occurs as a result of a violation of own communicated ethical or moral standards of a brand (Hoffmann et al., 2020), based on the purpose and form of the violation, the hypocritical behavior of brands could be actualized in various ways. Wagner et al. (2020) claim that such differing reflections of brand hypocrisy could be caused by different conceptual routes driven by deceptive practices and mere inconsistent behaviors. In order to understand the different types of brand hypocrisy, Guèvremont (2019) suggests four dimensions: image, message, social, and mission hypocrisy. Image hypocrisy refers to a brand’s deception and failure to follow through on its promises. Message hypocrisy refers to a brand’s communications that promote unrealistic principles and unattainable aspirations for customers. Social hypocrisy refers to a brand’s social actions that are unrelated to its core values and are viewed as solely strategic. Finally, mission hypocrisy, which this research focuses on, refers to a brand pretending that negative effects on people or society do not exist, even though it has negative, unknown effects on people or society.

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), people perceive events and develop attitudes based on those perceptions, which then influence their behavioral outcomes. This theory can help understand the indirect effects of various factors, such as brand hypocrisy, on behavioral outcomes through perception and attitude. Therefore, the Theory of Planned Behavior provides a useful framework for understanding the relationship between brand hypocrisy and behavioral outcomes (He & Lai, 2014). When brands do not align their actions with their claims, individuals perceive them as hypocritical, and this negatively impacts their attitudes, and behaviors towards the brand (Wagner et al., 2009). Thus, hypocrisy is an important determinant of the assessment process and behavioral outcomes of individuals, where it mostly has destructive effects (Arli et al., 2017; Gabrielli et al., 2021). For the assessment process, brand image and brand evaluations stand out as important factors. Since the brand image is “perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory’’ (Keller, 1993, p. 3), it strongly expresses individuals’ perceptions (Aaker, 1991; Faircloth et al., 2001; Keller, 1998). On the other hand, brand evaluations, which are “the consumer’s overall assessment of a brand – whether good or bad” (Low & Lamb, 2000, p. 352), clearly indicate the attitude of individuals attached to the brand (Assiouras et al., 2013; Dawar & Pillutla, 2000; Lei et al., 2012; Low & Lamb, 2000). Therefore, brand image and brand evaluation play a key role in the assessment process, and brand hypocrisy is expected to negatively affect both concepts (Guèvremont & Grohmann, 2018; Hora et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2009; Zhigang et al., 2020).

When focused on behavioral outcomes, Wagner et al. (2020) explain them as boycotting, word-of-mouth (WOM), and withdrawal behavior. Weiner’s (1980) attribution-emotion-action model helps to understand the potential results of brand hypocrisy among these behaviors, as it connects ethical and moral concerns to behavioral outcomes. According to the model, when individuals face a negative event that has occurred due to a specific reason, they assess the information based on their moral beliefs and attributes and generate a desire to punish the subject (Gabrielli et al., 2021). Therefore, brand hypocrisy could result in nWOM (Grégoire & Fisher, 2006). On the other hand, some individuals could react more passively and prefer to avoid relevant brands to prevent further damage (Grégoire et al., 2009; Weiner, 1980). Such behavior could cause brand distance (Guèvremont, 2019). It is important to note that even though punishment (nWOM) and avoidance (brand distance) are different desires, they can coexist (Grégoire et al., 2009, p. 19) and positive direct effects of brand hypocrisy are expected on both behavioral outcomes (Grégoire et al., 2009; Guèvremont, 2019; Janney & Gove, 2011; Kavaliauskė & Simanavičiūtė, 2015; Zhao & Zhou, 2017; Zhigang et al., 2020). Based on the explanations above, the following hypotheses are suggested:

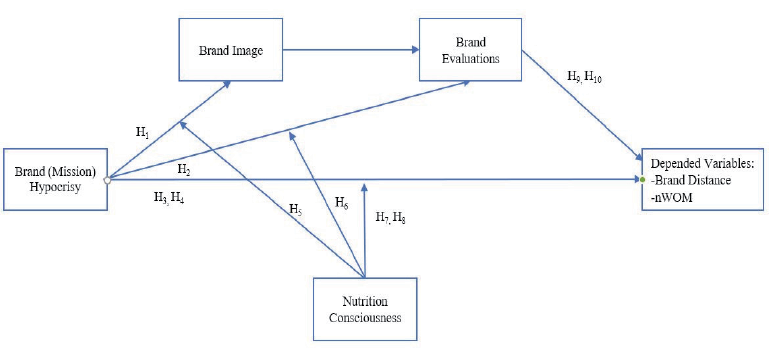

H1: Brand hypocrisy has a negative direct effect on brand image.

H2: Brand hypocrisy has a negative direct effect on brand evaluations.

H3: Brand hypocrisy has a positive direct effect on brand distance.

H4: Brand hypocrisy has a positive direct effect on nWOM.

2.2. Moderating Role of Nutrition Consciousness

Nowadays, diet-related diseases such as obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are quite prevalent among individuals (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012). Furthermore, such diseases could cause mental symptoms of depression and emotional disorders as well (Choi et al., 2021). Therefore, diet-related problems have led to increased awareness of the issue (Thomas & Mills, 2006), and many people have begun to change their consumption patterns in order to lead a healthier life (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012). As a result, today most people pay attention to consuming healthy food (Neciunskas, 2022) and trying to make dieting a lifestyle since diets that include a range of fruits and vegetables daily, whole grains, and restricted or moderate consumption of low-fat meats and dairy products have been demonstrated to help prevent numerous chronic diseases (Pawlak & Colby, 2009).

The path to a healthy life is through healthy behaviors, and behaving healthily is only possible with a consciousness of health. Therefore, health consciousness, which is the degree to which individuals actively engage in managing and participating in health-related activities (Moorman & Matulich, 1993), has been studied as a key driver of healthy behavior (Lee et al., 2014). As people become more health-conscious, their consciousness of nutrition has increased, too (Hwang & Cranage, 2010) because consuming healthy food is one of the primary steps of engaging in health-conscious behavior (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012), and ‘nutrition consciousness’ plays a vital role in individuals’ evaluations and choices for food (Ares et al., 2008; Thomas & Mills, 2006). Saegert and Young (1982) define nutrition consciousness as individuals’ general knowledge of food, which is independent of healthy food attitudes and reflects their broad tendency towards consumption preferences. As individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors towards foods can vary depending on their level of consciousness (Lee et al., 2014), many scholars have considered nutrition consciousness as a moderator in their research (Ares et al., 2008; Aydınoğlu & Krishna, 2011; Lee et al., 2014). When the effects of nutrition consciousness are investigated, we see that individuals’ nutrition knowledge affects their information processing (Steinhauser & Hamm, 2018), general eating behaviors (Aboulnasr & Sivaraman, 2010; Bower et al., 2003), and purchase intentions (Lockie et al., 2002). Also, conscious individuals are more critical in evaluating food (Hwang & Cranage, 2010) and have stronger reactions to the offering of healthy foods compared to their counterparts (Lee et al., 2014). Furthermore, individuals with a higher level of nutrition consciousness also tend to have a higher engagement with healthy food, while individuals with lower nutrition consciousness are more likely to choose unhealthy foods (Huang et al., 2022; Prasad et al., 2008). Finally, nutritional knowledge causes people to be more concerned about food-related risks (Hsu et al., 2019; Siegrist et al., 2022), where individuals with a higher nutrition consciousness make food selection more carefully to prevent potential harm to their health (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012). When considering the increased skeptical behaviors of individuals who scrutinize all types of brand actions (Guèvremont, 2019), their nutrition consciousness levels may explain a lot about the results of brand hypocrisy. Therefore, I propose the following hypotheses:

H5: Nutrition consciousness moderates the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand image. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

H6: Nutrition consciousness moderates the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand evaluations. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

H7: Nutrition consciousness moderates the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand distance. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

H8: Nutrition consciousness moderates the effect of brand hypocrisy on nWOM. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

2.3. Moderating Role of Nutrition Consciousness on the Indirect Effects of Brand Hypocrisy

Individual values and intentions may be influenced by the perception of brand hypocrisy (Alicke, 2000) and lead to negative behaviors such as brand distance and nWOM (Grégoire & Fisher, 2006; Grégoire et al., 2009; Guèvremont, 2019; Kavaliauskė & Simanavičiūtė, 2015; Zhigang et al., 2020). However, the proposed link may not be straightforward (Hur & Kim, 2020). In other words, there could be underlying mechanisms that further explain the process (Zhigang & Haoming, 2020). For instance, while brand hypocrisy is a major determinant of customer perception and evaluations (Wagner et al., 2009), brand image and brand evaluations can constitute the relevant assessment process, as noted in the preceding section. This understanding also overlaps with the Theory of Planned Behavior, which explains the role of perceptions and attitudes in the process leading to behavioral outcomes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The relationship between brand image and brand evaluations (Kim et al., 2017; Srikatanyoo & Gnoth, 2002) as well as their individual mediating functions have been well-discussed in the literature (He & Lai, 2014; Klein & Dawar, 2004). However, the effect of their serial mediation is not clearly explained. Finally, the moderating effect of nutrition consciousness is discussed previously (Ares et al., 2008; Aydınoğlu & Krishna, 2011; Lee et al., 2014), and it is expected as indirect effects of brand hypocrisy on both behavioral outcomes. Therefore, I propose the following moderated mediation hypotheses to test both research models:

H9: Brand image and brand evaluations serially mediate the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand distance. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

H10: Brand image and brand evaluations serially mediate the effect of brand hypocrisy on nWOM. This effect is only valid for a high level of nutrition consciousness.

Figure 1

Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Pre-test for Determining a Brand

The increasing awareness of nutrition affects the evaluation process of individuals for food brands (Steinhauser & Hamm, 2018). Therefore, “food” was chosen as the product category for the study. A pre-test was conducted to determine which food brand is considered hypocritical by most individuals. The results of the pre-test (n = 32) showed that a large proportion of participants (78%) believed the activities of a global fast-food brand to be hypocritical. However, to avoid any ethical or legal consequences, the brand’s name was referred to as “A brand” and was not specified in any part of the research1.

3.2. Data Collection

The study was conducted with the approval of the University of Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Ethics Board, and the data was collected from adult internet users living in Turkey. Participants were reached through convenience and snowball sampling techniques, and the questionnaire was directed online. According to the results of Monte Carlo power analysis (Schoemann et al., 2017), the sample size was determined as approximately 500 participants. As a result of eliminating missing and improper questionnaires, the study was carried out with 463 participants, including 244 females (52.7%) and 219 males (47.3%) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics (N = 463)

|

|

N |

% |

|

N |

% |

|

Gender |

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

Male |

219 |

47.3 |

Secondary School |

2 |

.4 |

|

Female |

244 |

52.7 |

High School |

44 |

9.5 |

|

Age |

|

|

Associate Degree |

25 |

5.4 |

|

18-25 |

101 |

21.8 |

Bachelor’s |

192 |

41.5 |

|

26-35 |

159 |

34.3 |

Master’s |

130 |

28.1 |

|

36-45 |

117 |

25.3 |

PhD |

70 |

15.1 |

|

46-55 |

59 |

12.7 |

Fast food consumption frequency |

|

|

|

≥ 56 |

27 |

5.8 |

Never |

18 |

3.9 |

|

Income |

|

|

Once a week |

71 |

15.3 |

|

≤ 2825 TRY |

110 |

23.8 |

2-4 times a week |

49 |

10.6 |

|

2826-5000 TRY |

100 |

21.6 |

Once in 2 weeks |

111 |

24 |

|

5001-8000 TRY |

143 |

30.9 |

Once a month |

89 |

19.2 |

|

8001-11.000 TRY |

39 |

8.4 |

A few times a year |

125 |

27 |

|

≥ 11.001 TRY |

71 |

15.3 |

|

|

|

|

Note. TRY= Turkish Lira (1 Euro= 16.30 TRY) |

|||||

3.3. Measures

Within the scope of the study, existing scales were used. The scales were modified and adapted into Turkish with the help of bilingual experts, and then retranslated into English to assure consistency (Munday, 2013). The survey was composed of structures including brand (mission) hypocrisy (Guèvremont, 2019), brand image (Ansary & Hashim, 2018; Chang & Chieng, 2006), brand evaluations (Assiouras et al., 2013; Dawar & Pillutla, 2000; Lei et al., 2012), brand distance (Grégoire et al., 2009; Guèvremont, 2019), negative word of mouth (Alexandrov et al., 2013), general nutrition consciousness (Aydınoğlu & Krishna, 2011; Saegert & Young, 1982), and demographics (including gender, age, income, education, and fast-food consumption frequency). All scales (see the Appendix for details) were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale and provided good results both for reliability and validity (see Table 2).

Table 2

Measurement Scales

|

|

Items |

Means |

SD |

Cronbach’s |

AVE |

CR |

|

Brand (mission) hypocrisy |

3 |

3.74 |

1.15 |

.929 |

.773 |

.911 |

|

Brand image |

5 |

3.02 |

.91 |

.819 |

.570 |

.865 |

|

Brand evaluations |

6 |

2.94 |

.94 |

.938 |

.610 |

.903 |

|

Brand distance |

5 |

2.91 |

1.16 |

.972 |

.738 |

.933 |

|

nWOM |

3 |

3.09 |

1.04 |

.901 |

.708 |

.877 |

|

Nutrition consciousness |

5 |

2.89 |

.89 |

.864 |

.579 |

.873 |

|

Note. Confirmatory factor analysis results (χ2/df= 3.742 (p <.001), GFI= .841, NFI= .907, IFI= .930, CFI= .930, RMSEA= .077). |

||||||

3.4. Analysis and Results

Before testing the hypotheses, discriminant validity and variance inflation factor (VIF) were tested. The Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity was applied, and it was found that the square root of the average variance extracted by the construct was greater than the correlation between the construct and any other construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Additionally, to avoid the issue of multicollinearity, the VIF values should be below a threshold value of 5 (Hair et al., 2021). According to the results of the analysis, the Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity was met, and no multicollinearity problem was found (see Table 3).

Table 3

Discriminant Validity and VIF Values

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

VIF |

|

1. Brand (mission) hypocrisy |

.879 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.417 |

|

2. Brand image |

-.070 |

.754 |

|

|

|

|

1.830 |

|

3. Brand evaluations |

-.391** |

.641** |

.781 |

|

|

|

2.603 |

|

4. Brand distance |

.445** |

-.346** |

-.583** |

.859 |

|

|

2.534 |

|

5. nWOM |

.420** |

-.328** |

-.575** |

.737** |

.841 |

|

2.435 |

|

6. Nutrition consciousness |

.339** |

-.274** |

-.410** |

.484** |

.470** |

.760 |

1.407 |

|

Note. ** represents p<.01. |

|||||||

Then, Process macro (Hayes, 2012; Muller et al., 2005) was used for hypothesis testing. The analysis was performed with 10,000 bootstrap estimation resamples, 95% confidence intervals, and model 85 was applied in the macro. The fast-food consumption frequency of individuals was included in the analysis as the control variable (Marlow & Shiers, 2012). Finally, even though nutrition consciousness is a continuous variable, with a similar understanding to previous studies (see Aydınoğlu & Krishna, 2011; Lee et al., 2014; Smeesters et al., 2010), I treated it as a categorical variable, where the “median split” technique was used.

3.4.1. Testing the direct effects of brand hypocrisy. Within the scope of the analysis for direct effects, it was unexpectedly found that brand hypocrisy did not significantly affect brand image (B=.0778; t=1.6429; p=.1011). On the other hand, it is determined that brand hypocrisy has a significant effect on brand evaluations (B=-.3127; t=-9.2168; p<.001), brand distance (B=.2203; t=4.2282; p<.001), and nWOM (B=.2118; t=4.5150; p<.001). According to these results, while the H1 hypothesis is not supported, H2, H3, and H4 are supported.

3.4.2. Testing the moderating role of nutrition consciousness. According to the results of the analysis for moderating effects, brand hypocrisy and nutrition consciousness have a significant interaction effect on brand image (B=-.2209; t=-2.9522; p<.01), and this effect is only valid for consumers with high levels of nutrition consciousness (B=-1430; t=-2.4722; p<.05). Thus, H5 is supported. On the contrary, the moderating effect of nutrition consciousness for the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand evaluations (B=.1125; t=2.0858; p<.05) is valid for both high (B=-.2002; t=-4.8145; p<.001) and low (B =-.3127; t=-9.2168; p<.001) nutrition consciousness levels. However, this effect is theoretically expected only for the high level of nutritional consciousness. Therefore, H6 is not supported. In addition, no significant moderating effect of nutrition consciousness was found on the impact of brand hypocrisy on brand distance (B=.0337; t=.4468; p=.6552), and H7 is not supported. Similarly, the interaction effect of brand hypocrisy and nutrition consciousness on nWOM was found to be unexpectedly insignificant (B=-.0886; t=-1.2877; p=.1985). Hence, H8 is not supported.

3.4.3. Testing the moderating role of nutrition consciousness in the indirect effects of brand hypocrisy. Finally, the hypotheses for the moderated serial mediation effects were tested. Brand image and brand evaluations serially mediate the indirect effect of brand hypocrisy on the brand distance (CI: from .0103 to .1399). As expected, the relevant serial mediation effect is only valid for individuals with high nutrition consciousness (B=.0434; CI: from .0030 to .0986). Similarly, brand image and brand evaluations also serially mediate the indirect effect of brand hypocrisy on the nWOM (CI: from .0109 to .1325), where this effect is only valid for individuals with high nutrition consciousness, too (B=.0420; CI: from .0035 to .0908). Based on these results, the proposed research models for moderated serial mediation and hypotheses H9 and H10 are supported.

Table 4

Hypotheses Results

|

Relation |

R2 |

B |

t value |

LLCI |

ULCI |

Hypothesis |

|

B. hypocrisy B. image |

.0819 |

.0778 |

1.6429 |

-.0153 |

.1709 |

H1 (NS) |

|

B. hypocrisy B. evaluations |

.5602 |

-.3127 |

-9.2168*** |

-.3794 |

-.2460 |

H2 (S) |

|

B. hypocrisy B. distance |

.4456 |

.2203 |

4.2282*** |

.1192 |

.3214 |

H3 (S) |

|

B. hypocrisy nWOM |

.4223 |

.2118 |

4.5150*** |

.1196 |

.3040 |

H4 (S) |

|

B. hypocrisy*NC B. image |

.0994 |

-.2209 |

-2.9522** |

-.3679 |

-.0738 |

H5 (S) |

|

B. hypocrisy*NCB. evaluations |

.5644 |

.1125 |

2.0858* |

.0065 |

.2185 |

H6 (NS) |

|

B. hypocrisy*NC B. distance |

.4458 |

.0337 |

.4468 |

-.1146 |

.1820 |

H7 (NS) |

|

B. hypocrisy*NC nWOM |

.4244 |

-.0886 |

-1.2877 |

-.2238 |

.0466 |

H8 (NS) |

|

Research model for B. distance |

- |

.0434 |

- |

.0030 |

.0986 |

H9 (S) |

|

Research model for nWOM |

- |

.0420 |

- |

.0035 |

.0908 |

H10 (S) |

|

FFCF B. image |

- |

-.0608 |

-2.2320* |

-.1143 |

-.0073 |

n/a |

|

FFCF B. evaluations |

- |

-.0753 |

-3.8484*** |

-.1137 |

-.0368 |

n/a |

|

FFCF B. distance |

- |

.0460 |

1.6631 |

-.0084 |

.1004 |

n/a |

|

FFCF nWOM |

- |

-.0045 |

-.1773 |

-.0541 |

.0451 |

n/a |

|

Note. B= unstandardized coefficient; LLCI or ULCI= lower level or upper level confidence intervals; NC= nutrition consciousness; FFCF= fast-food consumption frequency; S= supported; NS= not supported; n/a = not applicable; ***: p<.001; **: p<.01; *: p<.05. |

||||||

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study aimed to investigate the serial mediation effect of brand image and brand evaluations of the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand distance and nWOM, and the moderation role of nutrition consciousness on both indirect effects. According to the findings of the research, individuals’ perception of a brand as hypocritical negatively affects their evaluations of that brand (Wagner et al., 2009; Zhigang et al., 2020), causing them to avoid the brand (Guèvremont, 2019) and arousing a desire to punish the brand by spreading negative information as nWOM (Grégoire & Fisher, 2006). The negative effects of brand hypocrisy on brand evaluations support previous findings that indicate negative results of brand hypocrisy on attitudes toward the brand (Wagner et al., 2009; Zhigang et al., 2020). The results of the research also reveal that brand hypocrisy affects both passive (brand distance) and proactive (nWOM) behavioral outcomes, as expected (Grégoire et al., 2009; Guèvremont, 2019; Kavaliauskė & Simanavičiūtė, 2015). However, brand image is not directly affected by the hypocrisy perception of individuals. This result could be explained by the preference for a widely-known global fast-food brand within the scope of the research. As is known, having a strong brand image with a significant worldwide market share could provide advantages in the face of negative incidents (Ansary & Hashim, 2018; Hyun & Choi, 2018; Jo et al., 2003). On the other hand, judgments of brand image vary depending on individuals’ level of nutrition consciousness. For individuals with high nutrition consciousness, brand hypocrisy has a negative effect on brand image. This suggests that the protection of brand image is weakened for individuals who are highly aware of the importance of a healthy lifestyle, as they make more rigorous evaluations of the consequences of food brands’ behaviors (Steinhauser & Hamm, 2018). In contrast, the effects of brand hypocrisy on brand evaluations, brand distance, and nWOM do not differ based on individuals’ levels of nutrition consciousness. Finally, brand image and brand evaluations serially mediate the effect of brand hypocrisy on brand distance and nWOM, and these effects are only valid for high nutrition consciousness conditions. This result reveals that nutrition conconscious individuals have a more detailed assessment process for decision-making (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012; Thomas & Mills, 2006). In other words, for individuals with high nutrition consciousness, perceptual and attitudinal components play an important role in the process from brand hypocrisy to behavioral outcomes.

4.2. Managerial Implications

The findings of this study reveal that the perception of hypocrisy among individuals can have negative consequences for brands. For example, the perception of hypocrisy can lead to negative evaluations, increased brand distance, or nWOM for brands. Furthermore, since hypocrisy represents the ethical evaluation of a brand’s charitable or virtuous actions (Miao & Zhou, 2020), individuals’ perceptions of hypocrisy may cause feelings of betrayal (Kim et al., 2015) and even lead to intentions to switch to a different brand (Jung et al., 2021). As a result, the best practice for brands would be to be sincere and transparent, pay attention to ethical issues, and avoid situations that could be perceived as hypocritical by individuals (Arli et al., 2019). In addition, when individuals’ increased awareness of healthy living issues is taken into account, food brands are particularly recommended to be honest about product ingredients and their claims. To achieve this, intensifying communication efforts for information sharing, especially for customers with high nutrition consciousness, would be an appropriate approach, as they consider the issue more sensitively. If, for any reason, the brand is perceived as hypocritical, then implementing proactive strategies to address the situation would help to minimize the damage (Siomkos & Kurzbard, 1994; Wagner et al., 2009). Furthermore, improving brand image could provide some protection against the negative effects of brand hypocrisy. Finally, as seen in the cases of Volkswagen and McDonald’s, the actions of brands in response to accusations of hypocrisy may vary depending on the country in which they operate. For example, while these brands took serious actions in developed countries, it is observed that they did not act as seriously in developing countries (Arli et al., 2019; Junk & Sharon, 2019; Stender et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2009). However, the findings of this study, conducted in Turkey, suggest that perceptions of brand hypocrisy have negative consequences in developing countries as well. This suggests that the issue of healthy nutrition is not limited to developed countries, but is also relevant in developing countries. Therefore, brands are advised to act responsibly in all markets in which they operate.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. Firstly, the current study only focuses on food as a product category. Secondly, the results of this study only reflect the responses of individuals to one existing brand. Yet, individuals’ behaviors may vary across different products or brands. Finally, this study was only conducted in Turkey, and more research is needed to verify the findings in other developing countries to strengthen the developing country perspective.

It would be also beneficial to make additional suggestions for future research regardless of limitations. For instance, focusing on other dimensions of brand hypocrisy (image, message, and social hypocrisy) will enhance the understanding of the results of different types of hypocrisy. Additionally, testing alternative behavioral outcomes such as boycotting could provide further insight into the possible consequences of brand hypocrisy. Furthermore, exploring alternative mediators and moderators in the relationship between brand hypocrisy and consumer behaviors could expand our understanding of the topic. For example, investigating individuals’ emotional reactions such as negative emotions or perceived betrayal as potential mediators, or looking at intangible factors such as brand equity and corporate reputation as potential moderators could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of brand hypocrisy.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. The Free Press, New York.

Aboulnasr, K., & Sivaraman, A. (2010). Food for Thought: The Effect of Counterfactual Thinking on the Use of Nutrition Information. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.311

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Alexandrov, A., Lilly, B., & Babakus, E. (2013). The effects of social- and self-motives on the intentions to share positive and negative word of mouth. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(5), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0323-4

Alicke, M. D. (2000). Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin, 126(4), 556–574. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.556

Ansary, A., & Hashim, N. M. H. N. (2018). Brand image and equity: the mediating role of brand equity drivers and moderating effects of product type and word of mouth. Review of Managerial Science, 12(4), 969–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0235-2

Ares, G., Giménez, A., & Gámbaro, A. (2008). Influence of nutritional knowledge on perceived healthiness and willingness to try functional foods. Appetite, 51(3), 663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.061

Arli, D., Grace, A., Palmer, J., & Pham, C. (2017). Investigating the direct and indirect effects of corporate hypocrisy and perceived corporate reputation on consumers’ attitudes toward the company. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.04.002

Arli, D., van Esch, P., Northey, G., Lee, M. S. W., & Dimitriu, R. (2019). Hypocrisy, skepticism, and reputation: the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(6), 706–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-10-2018-0434

Assiouras, I., Ozgen, O., & Skourtis, G. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility in food industry in product-harm crises. British Food Journal, 115(1), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701311289902

Aydınoğlu, N. Z., & Krishna, A. (2011). Guiltless gluttony: The asymmetric effect of size labels on size perceptions and consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(6), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1086/657557

Baghi, I., & Gabrielli, V. (2019). The role of crisis typology and cultural belongingness in shaping consumers’ negative responses towards a faulty brand. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(5), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-03-2018-1806

Bower, J. A., Saadat, M. A., & Whitten, C. (2003). Effect of liking, information and consumer characteristics on purchase intention and willingness to pay more for a fat spread with a proven health benefit. Food Quality and Preference, 14(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-3293(02)00019-8

Chang, P. L., & Chieng, M. H. (2006). Building consumer–brand relationship: A cross-cultural experiential view. Psychology & Marketing, 23(11), 927–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20140

Choi, H., Northup, T., & Reid, L. N. (2021). How Health Consciousness and Health Literacy Influence Evaluative Responses to Nutrient-Content Claimed Messaging for an Unhealthy Food. Journal of Health Communication, 26(5), 350–359. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1946217

Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M. M. (2000). Impact of Product-Harm Crises on Brand Equity: The Moderating Role of Consumer Expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.215.18729

Dutta, S., & Pullig, C. (2011). Effectiveness of Corporate Responses to Brand Crises: The Role of Crisis Type and Response Strategies. Journal of Business Research, 64(12), 1281–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.01.013

Faircloth, J. B., Capella, L. M., & Alford, B. L. (2001). The Effect of Brand Attitude and Brand Image on Brand Equity. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(3), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2001.11501897

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gabrielli, V., Baghi, I., & Bergianti, F. (2021). Brand scandals within a corporate social responsibility partnership: asymmetrical effects on for-profit and non-profit brands. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(15-16), 1573–1604. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1928267

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. J. (2006). The effects of relationship quality on customer retaliation. Marketing Letters, 17(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-006-3796-4

Grégoire, Y., Laufer, D., & Tripp, T. M. (2010). A comprehensive model of customer direct and indirect revenge: understanding the effects of perceived greed and customer power. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(6), 738–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0186-5

Grégoire, Y., Tripp, T. M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: the effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.18

Guèvremont, A. (2019). Brand hypocrisy from a consumer perspective: scale development and validation. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(5), 598–613. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2017-1504

Guèvremont, A., & Grohmann, B. (2018). Does brand authenticity alleviate the effect of brand scandals? Journal of Brand Management, 25(4), 322–336. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0084-y

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [white paper]. Access Address: www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf, (Access date: 11.05.2020).

He, Y., & Lai, K. K. (2014). The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: the mediating role of brand image. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(3-4), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2012.661138

Hoffmann, N. C., Yin, J., & Hoffmann, S. (2020). Chain of blame: a multicountry study of consumer reactions towards supplier hypocrisy in global supply chains. Management International Review, 60(2), 247–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-020-00410-1

Hora, M., Bapuji, H., & Roth, A. V. (2011). Safety hazard and time to recall: the role of recall strategy, product defect type, and supply chain player in the U.S. toy industry. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7-8), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2011.06.006

Hsu, S. Y., Chang, C. C., & Lin, T. T. (2019). Triple bottom line model and food safety in organic food and conventional food in affecting perceived value and purchase intentions. British Food Journal, 121(2), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2017-0403

Huang, Z., Zhu, Y. D., Deng, J., & Wang, C. L. (2022). Marketing healthy diets: the impact of health consciousness on Chinese consumers’ food choices. Sustainability, 14(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042059

Hur, W. M., & Kim, Y. (2020). Customer reactions to bank hypocrisy: the moderating role of customer–company identification and brand equity. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(7), 1553–1574. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2020-0191

Hwang, J., & Cranage, D. (2010). Customer health perceptions of selected fast-food restaurants according to their nutritional knowledge and health consciousness. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 13(2), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378021003781174

Hyun, J. H., & Choi, S. B. (2018). Consumer purchase intention of a cosmetic product after the Fukushima nuclear incident. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(4), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6676

Iqbal, J., Yu, D., Zubair, M., Rasheed, M. I., Khizar, H. M. U., & Imran, M. (2021). Health consciousness, food safety concern, and consumer purchase intentions toward organic food: the role of consumer involvement and ecological motives. Sage Open, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/21582440211015727

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00984.x

Jo, M. S., Nakamoto, K., & Nelson, J. E. (2003). The shielding effects of brand image against lower quality countries-of-origin in global manufacturing. Journal of Business Research, 56(8), 637–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00307-1

Jung, J. C., & Sharon, E. (2019). The Volkswagen emissions scandal and its aftermath. GBOE, 38(4), 6-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21930

Jung, S., Bhaduri, G., & Ha-Brookshire, J. E. (2021). What to say and what to do: the determinants of corporate hypocrisy and its negative consequences for the customer–brand relationship. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(3), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2495

Kavaliauskė M., & Simanavičiūtė, E. (2015). Brand avoidance: relations between brand-related stimuli and negative emotions. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 44–77.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

Keller, K. L. (1998). Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring and Managing Brand Equity. Prentice Hall, New York.

Kim, H., Hur, W. M., & Yeo, J. (2015). Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability, 7(4), 3683–3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7043683

Kim, N., Chun, E., & Ko, E. (2017). Country of origin effects on brand image, brand evaluation, and purchase intention: a closer look at Seoul, New York, and Paris fashion collection. International Marketing Review, 34(2), 254–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-03-2015-0071

Klein, J., & Dawar, N. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product-harm crisis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.003

Kübler, R. V., Langmaack, M., Albers, S., & Hoyer, W. D. (2019). The impact of value-related crises on price and product-performance elasticities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(4), 776–794. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00702-5

Lee, K., Conklin, M., Cranage, D. A., & Lee, S. (2014). The role of perceived corporate social responsibility on providing healthful foods and nutrition information with health-consciousness as a moderator. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 37, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.10.005

Lei, J., Dawar, N., & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2012). Base-rate information in consumer attributions of product-harm crises. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(3), 336–348. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0197

Lockie, S., Lyons, K., Lawrence, G., & Mummery, K. (2002). Eating ‘green’: motivations behind organic food consumption in Australia. Sociologia Ruralis, 42(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00200

Low, G. S., & Lamb, C. W. (2000). The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 9(6), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420010356966

Maehle, N., Otnes, C., & Supphellen, M. (2011). Consumers’ perceptions of the dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(5), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.355

Mai, R., & Hoffmann, S. (2012). Taste lovers versus nutrition fact seekers: how health consciousness and self-efficacy determine the way consumers choose food products. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(4), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1390

Marlow, M. L., & Shiers, A. F. (2012). The relationship between fast food and obesity. Applied Eco. Letters, 19(16), 1633–1637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2011.648316

Miao, Q., & Zhou, J. (2020). Corporate hypocrisy and counterproductive work behavior: a moderated mediation model of organizational identification and perceived importance of CSR. Sustainability, 12(5), 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051847

Moorman, C., & Matulich, E. (1993). A model of consumers’ preventive health behaviors: the role of health motivation and health ability. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 208–228.

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

Munday, J. (2013). Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications. Routledge, Oxon.

Neciunskas, P. (2022). What’s wrong with being global: perception of healthiness of global food products. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 13(1), 50–70.

Pawlak, R., & Colby, S. (2009). Benefits, barriers, self-efficacy and knowledge regarding healthy foods; perception of African Americans living in Eastern North Carolina. Nutrition Research and Practice, 3(1), 56–63. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.1.56

Portal, S., Abratt, R., & Bendixen, M. (2019). The role of brand authenticity in developing brand trust. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27(8), 714–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1466828

Prasad, A., Strijnev, A., & Qin, Z. (2008). What can grocery basket data tell us about health consciousness? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(4), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2008.05.001

Saegert, J., & Young, E. A. (1982). Distinguishing between two different kinds of consumer nutrition knowledge. Advances in Consumer Research, 9(1), 342–347.

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Shklar, J. N. (1984). Ordinary Vices. Harvard University Press, New York.

Siegrist, M., Bearth, A., & Hartmann, C. (2022). The impacts of diet-related health consciousness, food disgust, nutrition knowledge, and the big five personality traits on perceived risks in the food domain. Food Quality and Preference, 96. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104441

Siomkos, G. J., & Kurzbard, G. (1994). The hidden crisis in product‐harm crisis management. European Journal of Marketing, 28(2), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569410055265

Smeesters, D., Mussweiler, T., & Mandel, N. (2010). The effects of thin and heavy media images on overweight and underweight consumers: social comparison processes and behavioral implications. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(6), 930–949. https://doi.org/10.1086/648688

Srikatanyoo, N., & Gnoth, J. (2002). Country image and international tertiary education. The Journal of Brand Management, 10(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540111

Steinhauser, J., & Hamm, U. (2018). Consumer and product-specific characteristics influencing the effect of nutrition, health and risk reduction claims on preferences and purchase behavior –a systematic review. Appetite, 127(2018), 303–323. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.012

Stender, S., Dyerberg, J., & Astrup, A. (2006). High levels of industrially produced trans-fat in popular fast foods. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(15), 1650–1652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc052959

Thomas Jr. L., & Mills, J. E. (2006). Consumer knowledge and expectations of restaurant menus and their governing legislation: a qualitative assessment. Journal of Foodservice, 17(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4506.2006.00015.x

Trump, R. K. (2014). Connected consumers’ responses to negative brand actions: the roles of transgression self-relevance and domain. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1824–1830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.12.007

Wagner, T., Korschun, D., & Troebs, C. C. (2020). Deconstructing corporate hypocrisy: a delineation of its behavioral, moral, and attributional facets. Journal of Business Research, 114, 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.041

Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., & Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.77

Weiner, B. (1980). A cognitive (attribution)-emotion-action model of motivated behavior: an analysis of judgments of help-giving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.186

Zhao, H., & Zhou, J. (2017). Review and prospect of research on pseudo-social responsibility of foreign enterprises. Journal of Capital University of Economics and Business, 19(1), 96–103.

Zhigang, W., & Haoming, Z. (2020). Consumer response to perceived hypocrisy in corporate social responsibility activities. SAGE Open, 10(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020922876

Zhigang, W., Lei, Z., & Xintao, L. (2020). Consumer response to corporate hypocrisy from the perspective of Expectation Confirmation Theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580114

Appendix 1

Measurements Used in the Study

|

Measurement Items |

Authors |

|

Brand (Mission) Hypocrisy • A brand that positively promotes a product associated with harmful consequences. • A brand that professes to be good for people but is not. • A brand that has negative consequences for people or society. |

Guevremont, 2019 |

|

Brand Image • This brand focuses on product quality. • This brand offers me a sense of group belonging. • This brand meets my sensory enjoyment. • This brand satisfies my desire. • This brand is one of the best brands in the sector. |

Ansary & Hashim, 2018; Chang & Chieng, 2006 |

|

Brand Evaluations • Unfavorable/favorable • Bad/good • Negative/positive • Not at all trustworthy/very trustworthy • Not at all dependable/very dependable • Not at all reliable/very reliable |

Assiouras et al., 2013; Dawar & Pillutla, 2000; Lei et al., 2012 |

|

Brand Distance • Keep the largest distance between this brand and me. • Avoid buying this brand in the future. • Not consume this brand. • Avoid this brand. • Stay away from this brand. |

Grégoire et al., 2009; Guevremont, 2019 |

|

Negative WOM • Warn my friends and relatives not to buy this brand. • Complain to my friends and relatives about this brand. • Say negative things about this brand to other people. |

Alexandrov et al., 2013 |

|

General Nutrition Consciousness • I read the nutrition labels on packaged foods for nutritional content and to ensure fat and salt are at or below an acceptable level. • I try to make sure for the food that I eat to have high nutritional value. • I eat the recommended daily amount of the food groups in the food pyramid. • I watch and listen for the latest information about nutrition practices. • I limit the amount of fat in my diet to one-third or less of my total daily calorie intake. |

Aydınoğlu & Krishna, 2011; Saegert & Young, 1982 |

1 During data collection for the main study, participants were given the following explanation: “A brand is one of the world’s leading fast-food brands operating in many countries, including Turkey.” They were then asked to respond to survey questions about the brand that came to their minds first. At the end of the survey, participants were asked an open-ended question, “Which brand came to your mind?” Only surveys that indicated the same brand name as the pre-test result were included in the research, and others were excluded.