Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 2(28), pp. 366–385 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.97

How Sexualised Images in Advertisements Influence the Attention and Preference of Consumers with a Modern View

Kristian Pentus

University of Tartu, Estonia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5395-9424

kristian.pentus@ut.ee

Mariia Ruusu

University of Tartu, Estonia

maria.ruusu@gmail.com

Andres Kuusik

University of Tartu, Estonia

andres.kuusik@ut.ee

Liudmyla Dorokhova (corresponding author)

University of Tartu, Estonia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3859-628X

liudmyla.dorokhova@ut.ee

Kerli Ploom

University of Tartu, Estonia

kerli.ploom@ut.ee

Abstract. This paper aims to determine how using sexualised images in advertisements influences the attention and preference of consumers with a modern attitude towards gender stereotypes.

This research used a methodological approach based on eye tracking of the perception of advertising images – an eye-tracking study measured how the general attitudes towards gender roles mediate attention. A control question for attitudes towards gender stereotypes was used. The degree of preference for advertising was also examined in the study.

The results show that sexual stimuli are not more eye-catching than non-sexual, as sexual advertisements do not capture attention faster and are not viewed for a longer time than non-sexual advertisements.

The originality and value of the study lies in the fact that the article supports the right marketing decisions to overcome gender stereotypes in advertising, to avoid advertising errors associated with unjustified sexualisation and eroticisation of visual advertising images and models. It also suggests directions for future research on various aspects of gender stereotypes in advertising.

Keywords: marketing, eye-tracking, gender stereotypes, perfume advertisements, sexual appeals in advertising

Received: 6/11/2022. Accepted: 26/5/2023

Copyright © 2023 Kristian Pentus, Mariia Ruusu, Andres Kuusik, Liudmyla Dorokhova, Kerli Ploom. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Consumers are exposed to advertisements daily, translating into millions of advertisements during their life (Pavel, 2014). Because the markets are overcrowded with media, there is high competition among advertisements to stand out. The content seen in advertisements can impact people’s behaviours, e.g., Pilelienė and Grigaliūnaitė (2016, p. 489) research suggests that “first visual impressions do often influence mid- and long-term human behaviour and are influenced by factors such as context”. Consequently, the practical application of various techniques in visual advertising is an essential and relevant scientific and practical task.

One of the widespread marketing techniques is using sexualised or erotic images and models to attract attention – the so-called sexually appealing advertisements. There are several previous studies whose results show that the use of sexualised images in advertising does have an effect on people’s behaviour and may have a positive outcome (Furnham & Mainaud, 2011; Leka et al., 2013; King et al., 2015; Wirtz et al., 2017).

The use of sexualisation in advertising has been associated with stereotypical gender roles. Previous studies (Grover & Hundal, 2014; Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008; Matthes et al., 2016; Pavel, 2014; Grau & Zotos, 2016) have shown that females in advertisements are frequently portrayed sexually, decoratively, or traditionally as housewives, whereas men, when used in a sexualised manner, are often portrayed by their physical characteristics, such as being muscular and tall (Baxter et al., 2016).

However, the attitude towards gender roles has been changing, especially the views towards the sexual representation of women. Therefore, research suggests that people may no longer prefer sexual advertisements to non-sexual alternatives (Lull & Bushman, 2015; Haines et al., 2016; Grover & Hundal, 2014). Also, the distracting effect of sexual images in advertising (Cummins et al., 2021; Gong et al., 2021) may lead to unwanted consumer gaze behaviour, negative attitudes and unfavourable brand image.

While choice and preference can strongly affect society’s expectations, attention and gaze behaviour are freer from these expectations. Eye-tracking research method, which is related to subconscious cognitive processing, shows which advertisements people look at first and which most. Previous work has examined how genders differ in gaze behaviour (Yoon Min & Kun Chang, 2018; Kraines et al., 2017; Rupp & Wallen, 2007). Far less has been done to see how gender roles (stereotypes) portrayed in advertisements affect the gaze behaviour of men and women with regard to sexual versus non-sexual advertisements.

This research will use a methodological approach based on an eye-tracking study aiming to find out how using sexualised images in advertisements influences the attention and preference of consumers with a modern attitude towards gender stereotypes. In addition, the differences between male and female models portrayed in either sexualised or non-sexualized advertisements were examined. We used static image-based advertisements, also referred to as print advertisements.

In conclusion, this study confirms the theoretical assumptions about the importance of studying the influence of changing views towards gender stereotypes in sexually appealing advertisements and its effect on gaze behaviour and preferences. Based on the results obtained, practical implications are suggested.

2. Literature Review: Advertisements, Gender Roles, and Stereotypes

Previous literature has shown gender roles portrayed in advertisements (Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008; Baxter et al., 2016; Pavel, 2014; Grover & Hundal, 2014; Matthes et al., 2016). Notably, social scientists have been interested in using detailed advertisements in their studies to analyse gender stereotypes (Milner & Collins, 2000). Some scholars argue that it is the outcome of the “feminist movement” that focuses on bringing equality between women and men in media or critical approaches towards traditional gender categories (male and female), where LGBTQ+ people are omitted (Araüna et al., 2017).

Stereotypes can be defined in different ways, but based on Hilton and Hippel (1996), the authors consider stereotypes as “beliefs about the characteristics, attributes, and behaviours of members of certain groups”. Advertisements contain various stereotypes, e.g., based on people’s appearance, gender, nationality, and sexual orientation (Pavel, 2014). A gender stereotype is often used in advertisements.

According to Deaux and Lewis (1984), there are four gender stereotypes: trait descriptors (emotional, self-confident), physical characteristics (height, weight), role behaviours (taking care of finance, taking care of children) and occupational roles (firefighter, housewife). However, they believe that only physical appearance is the most dominant gender stereotype, which is why it is the most “potent source” of stereotypes. Of all the components, occupational status and physical attributes are the most stereotypical (Tartaglia & Rollero, 2015). Therefore, the gender role explored in this research is the physical appearance of females and males. More specifically, the authors look at portraying sexual appearance vs non-sexual appearance.

Tartaglia and Rollero (2015) define gender stereotypes as a “set of beliefs concerning attributes that are supposed to differentiate women and men”, which means that gender stereotypes are preconceived ideas about the abilities and qualities of men and women. These roles are commonly rooted in cultures and can be challenging to change. Gender roles can make people believe they are only suitable for one social or professional role. Thus, they often specify which role suits each gender (firefighter, nurse) (Eagly & Karau, 2002). So, this has also affected how female and male models are pictured in advertisements.

Many researchers who studied female roles in advertisements (Grover & Hundal, 2014; Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008; Matthes et al., 2016; Pavel, 2014) noticed that women’s roles are undervalued at a professional level, and women are often sexually portrayed.

Women are primarily shown in decorative roles or family-oriented roles such as decoration for their beauty or as housewives (Grau & Zotos, 2016). The decorative role denotes a passive model which aims to use sexual stimulus to attract consumers to buy goods or services (Grover & Hundal, 2014). Men are commonly shown as more independent, with authority and in professional roles without regard to physical attributes (Reichert & Carpenter, 2004). However, Baxter et al. (2016) also argue that male gender roles in advertising are often seen as a “representation of traditional masculinity” or as a “sex object.”

In addition, researchers have shown that advertising on printed ads has an impact on people’s perceptions and their body image (Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008). For example, Kilbourne (2001) argues that depicting women in advertisements can lower their confidence and support health issues like eating disorders. Furthermore, Pollay and Gallagher (1990) point out that advertisement imagery has significantly impacted how stereotypes are justified among larger communities over the years.

In advertising, gender is used as a primary segmentation variable in developing marketing strategies and defining target groups (Matthes et al., 2016; Milner & Collins, 2000; Daechun & Sanghoon, 2007). In addition, “gender advertising” takes advantage of gender roles and gender-specific fantasies to customise it for a particular audience (Grover & Hundal, 2014). The research conducted by Plakoyiannaki et al. (2008) concluded that women in advertising have very stereotypical roles despite the type of audience: for female or male audiences, women were portrayed as decorative, dependent, and non-traditional roles, and for a general audience, women were portrayed as housewives or equal to men. Furthermore, Latour (1990) and Lass and Hart (2010) argue that in advertisements, male audiences accept stereotypical roles, such as female nudity, better than the female audience. Wyllie et al. (2015) research shows that women react more positively to mild sexual stimuli than explicit sexual stimuli, where females are depicted in a highly sexual way (nudity or sexual acts). Women and men both get recognition for their physical appearances; more often than not, women get evaluated by their looks (Langlois et al., 2000).

Plakoyiannaki and Zotos (2009) research emphasises that women are depicted differently advertising different product categories, hedonic and utilitarian products. Hedonic products are mainly related to sensory attributes that generate consummatory effective gratification, whereas utilitarian products are related to functional attributes that fulfil instrumental needs (Crowley et al., 1992). Hedonic products can be, for example, travelling trips or music devices. Utilitarian products can be rain boots or personal hygiene products. Women are portrayed as decorative when advertising hedonic products, while advertisements of utilitarian products involve gender roles such as non-traditional, traditional, and decorative (Plakoyiannaki & Zotos, 2009).

Therefore, product categories, especially hedonic products, are related to how women are seen in advertisements in decorative roles. So, Matthes et al. (2016) argue that globally, women are more often than men linked with beauty, personal and cleaning products in advertisements. In advertisements, men usually sell technological or leisure products (Furnham & Farragher, 2000). Hence, the focus of this research is the product category of more hedonic products. Physical gender attributes are used in advertisements because they most dominantly capture consumers’ attention (Tartaglia & Rollero, 2015; Deaux & Lewis, 1984).

The concept of gender roles has become a phenomenon of cultural conscience. Women nowadays are more prominent in their professional roles and, at a younger age, perform better than boys in some areas of education (Adema, 2013). However, female characters in advertisements do not mirror contemporary gender roles (Plakoyiannaki & Zotos, 2009). Traditional male gender roles have moved to represent more modern roles of men in the past few years (Grau & Zotos, 2016). For example, men are portrayed as spending time with their children and are shown in more egalitarian roles. However, people continue to stereotype women and men based on specific characteristics (Haines et al., 2016). They argue that despite the change in attitudes and acceptance of women and men in modern, non-traditional roles, people perceive gender differences the same way they did some time ago.

Overall, the public perception of gender roles and sexuality is changing towards gender neutrality in advertising (Haines et al., 2016), and gender roles are more negatively perceived nowadays than centuries ago. For example, advertisements that overly sexualise women can bring out negative attitudes and feelings among consumers (Grover & Hundal, 2014). According to Ford and Latour (1996), the representation of gender in advertisements can have an impact on the corporate image they give consumers.

As known, an essential purpose of advertising is, in particular, the promotion of brands. Some studies have shown that the use of sexual appeal may have a positive impact on advertising outcomes, including capturing consumers’ attention, generating interest, affecting positively ad recognition and recall, and raising brand awareness (Furnham & Mainaud, 2011; Leka et al., 2013; King et al., 2015; Wirtz et al., 2017). However, their results are mixed, and sexual appeals may ‘distract’ advertising messages and cause negative promotion effectiveness. Among recent studies addressing this issue, the work by Cummins et al. (2021) devoted to the effect of visual distraction when using sexual elements in advertising is of considerable interest. It has been found that visual attention given to sexy models in such advertisements is higher than the attention paid to non-sexy models. As a result, attention to the advertising text and the brand suffered, which confirms the inappropriate use of sexual elements in advertising.

The first research question arising from the analysis of the literature, is the following: which advertisements (sexual or non-sexual) are noticed faster? That is, what is the speed (time) of attracting attention in both cases? Is it the same, and if not, which advertisement attracts attention faster?

Gong et al. (2021) confirm the distracting effect of sexual images in advertising: they increase visual attention to the sexualised model and decrease visual attention to non-sexual elements such as brand name, product image, and advertising text. This conclusion is confirmed by the study of Šula et al. (2017), which presents the results of the impact of erotic advertising on consumers on Instagram.

The second research question is which advertisements (sexual or non-sexual) are viewed first and whether this is affected by the gender of the advertisement viewer.

The research by Fidelis et al. (2017) is devoted to the influence of the degree of sexuality of advertising on brand memory. It confirms the conclusions of the researchers mentioned above. It compares the times of fixation of the consumer’s gaze on the elements “image” and “logo” in advertisements with and without a sexual appeal.

The general trend of changing consumer views on advertising that exploits sexual attractiveness is manifested globally and in individual markets, including for specific, local products. For example, Hwang et al. (2020) confirmed this in a study of Soju (Korean alcohol) brand advertising. An essential and revealing result is that visual attention and interest in the advertising model were higher for the face than for the body shape.

In recent years, sexualised advertising, to a certain extent, tends to turn into a taboo, which is increasingly characterised by characteristics and processes summarised in a fundamental study on eye tracking various taboos in advertising (Myers et al., 2020).

As people’s attitudes and perceptions towards gender roles change, this may also have implications for using physical appearance as a dominant gender stereotype in advertisements. Previous research on using sexual stimuli in advertising has yielded mixed results. Moreover, the change of stereotypical ideologies towards a more modern view adds further complexity to interpreting these results, e.g., in terms of consumer attention and preferences. This highlights the need for further research in this area and makes it relevant to study whether traditional gender stereotypes expressed in physical appearance capture consumers’ attention better than non-traditional roles and how they influence preferences.

The third research question concerns the comparison of the time characteristics of the response of women and men to both types of advertisements (sexual and non-sexual). Are these time characteristics the same for both groups or different, and what are these differences?

3. Research Methodology, Sample, and Used Advertisements

The research methodology consisted of an eye-tracking study to measure gaze behaviour and a control question to measure a person’s general attitude towards gender roles. Eye-tracking was used to measure the eye movements of the participants. Many researchers use eye tracking to see differences between genders (Yoon Min & Kun Chang, 2018; Kraines et al., 2017; Rupp & Wallen, 2007).

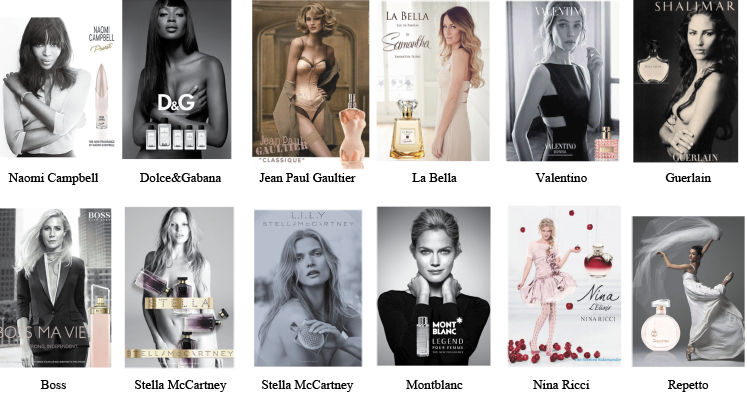

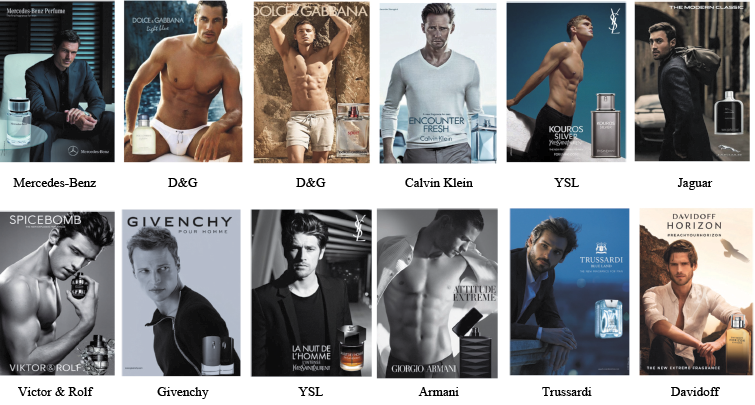

The first step in the research was to find suitable advertisements. The authors chose both sexualised and non-sexual advertisements. A hedonic product category (perfumes) was selected because their advertisements often portray female and male characters in a sexual way or as decoration for the product. Secondly, it was crucial to find similar advertisements regarding the type of layout, colour, and model in the advertisement. This minimised the effects of other factors on the design of the advertisement. Sexualised advertisements were selected according to the level of nudity and sexual suggestiveness. In this process, the authors chose over 40 different sexual and 40 different non-sexual advertisements. From these, the authors selected sexual advertisements that portrayed mild nudity. Advertisements with extreme nudity with text that referred to sexualisation or that portrayed some sort of gesture-based or pose-based suggestiveness of sexualisation were neglected. This was done to ensure that the effect we were observing was of one specific type.

In total, 20 perfume advertisements were selected, from which five portrayed male models in a sexual and five in a non-sexual way. Similarly, five advertisements were selected with female models portrayed in a sexual and another 5 in a non-sexual way.

In addition, two non-sexual male and two non-sexual female advertisements were selected as neutral pictures to distract the sample so that the research aim would not be too transparent in the experiment. All the advertisements were placed into the frame layout so that one frame consisted of two similar images – one sexual and another non-sexual (Appendices A & B).

The two visuals were placed on the far edges of the screen (resolution: 1920x1080), sexual advertisement on one side and non-sexual on the other. Hence, participants saw six frames of male and six frames of female advertisements. To examine which of these two types of advertisements (sexual vs non-sexual) caught more attention, it was important that the first gaze of the participants was in the middle of the screen and then moved to one or the other advertisement. Therefore, a red dot on a white background was placed before every frame.

Moreover, the authors created two different sequences in which the frames of advertisements were shown. For both sequences, two versions were created, where ads changed sides. For example, the participant saw a sexual picture on the left side of the frame and a non-sexual one on the right. Then the second participant saw the second sequence, meaning that the non-sexual advertisement was on the left and the sexual on the right side of the frame. This was necessary, as previous research has shown a left-side viewing bias due to left-to-right reading. Outing and Ruel (2004) and then Hill (2010) showed how the bottom right corner of the webpage was viewed last and the upper left corner first. This tendency to look to the left side of the screen first and longer has been proven multiple times after that (Hernandez et al., 2017; Afsari, 2018).

During the research, participants had to mouse-click on one of their preferred advertisements. After the click, they were shown the next pair of advertisements. The preference was not discreetly linked to liking or anything else, just their current top-of-head preference between the two options they were shown. This way, it was possible to investigate if participants chose the same advert they gazed at first. Tobii X2-60 remote eye-tracker was used, and the results were analysed using Tobii Pro Studio.

A control question was used before the research to determine attitudes towards gender ideology among participants. The general attitude towards gender roles can be measured with six categories. For this study, only one question was looked at, which addresses one category, “Working woman and relationship quality,” directly and one category, “Belief in separate gendered spheres”, indirectly (Davis & Greenstein, 2009). This enabled us to measure general attitudes towards gender roles and only include people with modern views.

The question used for this purpose was “Is it OK for the husband to take care of the kids and the wife to work” (Baxter et al., 2016). Only people who answered positively to this question and had more egalitarian and modern views towards gender roles were recruited for the eye-tracking research.

The sample consisted of 22 University of Tartu participants with normal eyesight; 11 women and 11 men aged 17 to 31 (mean age 21.86). The sample includes participants from 11 countries: Finland, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Russia, Ukraine, Croatia, Czech, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Japan. The sample had a modern view towards stereotypes, and no participants were neglected due to not having a modern view. Choosing only young students proved a sufficient selection constraint, meaning all recruited participants had a modern view.

4. Eye-Tracking Research Results and Generalized Findings

Eye-tracking variables time to first fixation (TFF) and total fixation duration (TFD) were used. Time to the first fixation in seconds shows how long it took for a person to notice the advertisement for the first time, or more simply, how long it takes from the advertisement appearing on the screen to direct one’s gaze to that stimulus. Total fixation duration is the sum of the duration for all fixations of a person for one advertisement.

Table 1 reflects our results and provides a general answer to the first research question. As noted above, some researchers suggest that participants would first look at sexual, stereotypical advertisements. Our TFF data shows that, on average, non-sexual advertisements caught attention faster. The average TFF of sexual advertisements is 1.14, and for non-sexual advertisements, 1.04 seconds. This means that participants looked at non-sexual advertisements first. A paired sample t-test showed no statistical differences between time noticing sexual and non-sexual advertisements. The Sig. (2-tailed) p-values were all greater than the common significance level of 0.05 ranging from 0.207 up to 0.916 seconds.

Table 1

Average Time to the First Fixation and Total Fixation duration of all the Advertisements

|

|

Average Time to First Fixation (in seconds) |

||

|

|

TFF |

For all advertisements shown |

For all advertisements shown |

|

Sexual |

1.14 |

0.69 |

1.59 |

|

Non-Sexual |

1.04 |

0.70 |

1.38 |

|

|

Total Fixation Duration (sum in seconds) |

||

|

|

TFD |

TFD on left |

TFD on right |

|

Sexual |

39.24 |

21.87 |

17.37 |

|

Non-Sexual |

46.58 |

23.19 |

17.37 |

We tested the difference between all sexual vs all non-sexual advertisements and the difference between each pair. The results reveal that sexual advertisements are not noticed faster.

Additional analysis was conducted on which side of the frame (left or right) sexual or non-sexual advertisements were placed. The advertisements on the left side, in general, are noticed substantially faster than on the right side (see Table 1). However, since the subjects of the sample are used to reading from left to right, this could be why left ads are viewed first. We placed the same advertisement on the left side for half of the sample and on the right for the other half, eliminating errors. The ads on the left were noticed faster because people in our sample are used to reading text from left to right.

The results of our experimental study answering the second research question are presented in Table 2. Sexual advertisements where male models are portrayed sexually and decorative are viewed at first compared to non-sexual male advertisements. However, one non-sexual advertisement was viewed faster than the sexual advertisement. This was a perfume ad from Jaguar where a male model was dressed classically, wearing a coat and a bag on his shoulder, and staring at the camera (see Appendix B).

Interestingly, the same pattern does not exist between the female sexual and non-sexual advertisements. The sample subjects mostly viewed non-sexual female advertisements first (see Table 2). However, also, in this case, there is an exception. Guerlain (sexual ad) has a shorter average time to first fixation (0.97), whereas in the case of Valentino (non-sexual ad), the average TFF time is 1.08. This means that participants viewed the Guerlain advertisement first.

The fastest-viewed was a non-sexual female model advertisement from Montblanc. There are no significant differences between genders. Both genders, in general, viewed non-sexual advertisements first. Male participants noticed non-sexual advertisements in 1.19 seconds on average, while female participants noticed them in 0.93 seconds.

Table 2

Generalised Results of the Eye-Tracking

|

|

Average Time to First |

Total Fixation |

Mouse Click Count |

|||

|

|

TFF |

TFF |

TFD |

TFD |

MCC |

MCC |

|

Armani (Sexual) vs YSL |

1.25 |

1.28 |

37.36 |

43.48 |

6 |

16 |

|

Dolce & Gabbana (Sexual) vs Mercedes-Benz |

0.88 |

1.40 |

31.18 |

40.84 |

3 |

19 |

|

Dolce & Gabbana (Sexual) vs Calvin Klein |

0.89 |

1.44 |

37.55 |

38.88 |

10 |

11 |

|

YSL (Sexual) vs Jaguar |

1.36 |

0.96 |

31.69 |

47.33 |

5 |

17 |

|

Victor & Rolf (Sexual) vs Givenchy |

1.07 |

1.16 |

39.54 |

49.72 |

7 |

14 |

|

Jean Paul Gaultier (Sexual) vs La Bella |

1.06 |

0.87 |

43.84 |

48.23 |

6 |

16 |

|

Dolce & Gabbana (Sexual) vs Naomi Campbell |

1.30 |

0.75 |

48.28 |

63.02 |

10 |

11 |

|

Guerlain (Sexual) vs Valentino |

0.97 |

1.08 |

38.35 |

44.37 |

4 |

18 |

|

Stella McCartney (Sexual) vs Boss |

1.34 |

0.80 |

41.55 |

45.10 |

4 |

18 |

|

Stella McCartney (Sexual) vs Montblanc |

1.30 |

0.68 |

43.09 |

44.83 |

5 |

16 |

The data obtained regarding the third research question, as well as the relationship between the considered aspects of the visual perception of sexual and non-sexual advertisements, and their features for both groups (men and women) are presented below.

In our experiments, women noticed non-sexual advertisements faster than men did. However, women also noticed sexual advertisements faster than men did. It took an average of 1.01 seconds to notice sexual advertisements for women and 1.22 seconds for men (Table 3).

Table 3

Average TFF and TFD Among Women and Men

|

|

Average Time (seconds) |

|

|

TFF |

TFD |

|

|

All sexual advertisements seen by men |

1.22 |

2.078 |

|

All sexual advertisements seen by women |

1.01 |

1.644 |

|

All non-sexual advertisements seen by men |

1.19 |

2.453 |

|

All non-sexual advertisements seen by women |

0.93 |

1.893 |

To acquire comprehensive results, total fixation duration must be taken into consideration. It reflects how long it took for the participants to view the advertisement. For example (see Table 1), overall TFD for sexual advertisements is 39.24 seconds. For non-sexual ads, TFD is 46.58, meaning that these advertisements were viewed the longest.

The results show that all non-sexual advertisements were viewed longer than sexual advertisements (see Table 2). According to the results (see Table 3), non-sexual advertisements were viewed longer than sexual ads among both women and men. Non-sexual advertisements were viewed on average for 2.453 seconds among men and 1.893 seconds among women. However, a paired sample t-test showed no statistically significant differences between the TFD of the pairs of sexual and non-sexual advertisements. The Sig. (2-tailed) p-values were all greater than 0.05, ranging from 0.411 to 0.812. While we cannot say that non-sexual ads were seen statistically significantly faster, we can state that sexual advertisements do not outperform non-sexual advertisements. Sexual advertisements were viewed for 2.078 seconds among men and 1.644 seconds among women. Therefore, there are no noticeable differences between men and women, although generally, men viewed both types of advertisements longer than women.

Mouse click count (MCC) was the third statistic needed for this research. MCC count shows which advertisement from the pairs was preferred more by participants. During the eye-tracking research, participants had to mouse-click the advertisement they preferred more. During the eye-tracking research, the sample subjects had to choose between sexual and non-sexual advertisements to continue going to the following research step. Overall, all participants preferred non-sexual advertisements over sexual ones (see Table 2). In the table, for four instances, the MCC does not add up to the sample size of 22. This is due to a procedure of how the advertisement pairs were shown. Participants would be shown the following pair as soon as they clicked. Four people clicked on an area in which no advertisement was present. Hence the next advertisement pair was shown, and no click on the advertisement was registered.

Moreover, there is an equivalence between TFD and MCC. Table 2 shows the sum of the mouse clicks per advertisement, and the results are similar to TFD: Non-sexual advertisements were preferred more than sexual ads. Therefore, advertisements that were viewed for a longer time were also preferred. However, no causal effects can be derived from this data.

Overall, sexual advertisements did not have more impact than non-sexual advertisements regarding time to first fixation (TFF) and total fixation duration (TFD). Sexual advertisements were not noticed faster and were not viewed longer. Non-sexual advertisements were preferred more than sexual advertisements. However, sexual male advertisements were noticed faster than non-sexual male advertisements. Based on a paired sample t-test, there were no statistically significant differences in average TFF nor TFD between sexual and non-sexual adverts. The Sig. (2-tailed) p-values were all greater than the common significance level of 0.05, ranging from 0.132 to 0.711. Non-sexual advertisements of females were noticed faster than sexual female advertisements, although both advertisement types had some exceptions. In the case of total fixation duration, non-sexual advertisements were viewed longer regardless of whether the advertisements contained female or male models.

There was no apparent difference between male and female participants. Both, on average, noticed non-sexual advertisements first, and women noticed non-sexual advertisements faster than men. Moreover, TFD did not show substantial differences among genders. Men viewed both advertisement types longer: sexual ads about 2.078 seconds, on average, and non-sexual ads 2.453 seconds. Women used less time gazing at the advertisements: sexual – 1.644 and non-sexual – 1.893 (see Table 3).

5. Discussion

Based on previous research, it could be expected that sexual advertisements that attract sexual stimuli would catch attention better. This logic is seen in advertisements for hedonic products, which, where applicable, often use sexualised images of models in their advertisements. However, the attitudes towards gender roles and stereotypes have evolved significantly over time, with increasing emphasis on promoting gender equality and challenging traditional gender norms.

The results of eye-tracking experiments show that sexual advertisements do not outperform non-sexual ads; they are noticed at a similar speed and viewed for a similar time. There are no statistically significant differences in total viewing time and noticing time for sexual and non-sexual advertisements. The results for the male and female participants are more or less the same, so there is no significant difference between the two genders of participants.

The results are also more or less similar to the male or female models shown in the advertisements. This altogether means that sexual stimuli are not more eye-catching than non-sexual. There is a growing trend towards gender neutrality in advertising (Haines et al., 2016), as contemporary audiences increasingly perceive traditional gender roles negatively compared to previous generations.

Advertisements that overly sexualise women can elicit negative attitudes and feelings among consumers (Grover & Hundal, 2014), potentially harming the brand image and diminishing the advertisement effectiveness. Our results did not show sexual advertisements to be preferred either, and more people preferred non-sexual advertisements. Some studies in the recent decade also indicate that consumers may increasingly prefer non-sexual advertisements to sexual alternatives (Lull & Bushman, 2015; Haines et al., 2016; Grover & Hundal, 2014), reflecting the broader shift in societal attitudes towards gender representation.

In this research, perfume products were generally not viewed in the advertisements; the model’s face, body, and text received more attention than the product and brand itself.

However, if products were placed in front of the model’s body, then the products were recognised, especially in sexual advertisements. Therefore, attracting consumers with only sexual content is not the right solution. The results of our study confirm that both women and men prefer non-sexual advertising.

Additional research is needed to determine why sexual commercials with male models are seen first, according to the time to first fixation (TFF) statistic. Another research direction could focus on how consumers’ advertising preferences influence their purchasing decisions. Further research is needed on gender roles, stereotypes, and discrimination in advertising, especially among the youth segment of consumers.

Hedonic product advertisements often have sexualised pictures of models. Our research shows that sexual advertisements are less preferred and less attention-grabbing than non-sexual advertisements.

These results showed that the attitude towards sexualising is changing, which could lead to companies changing their advertising campaign approach from gender stereotypically sexualised to less sexualised.

The sexualised advertisements do not catch more attention of young people, nor are they viewed faster. Sexualised advertisements can hinder the brand image, and non-sexual advertisements are preferred.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Advertisements have historically relied on physical appearance to reinforce gender stereotypes. The portrayal of sexual vs non-sexual appearance plays a crucial role in shaping consumer perceptions, with sexualised images often used to capture attention and create associations with the advertised product. This research showed that sexual appearance does not necessarily improve advertisements’ ability to catch attention. Sexual advertisements were not viewed faster than non-sexualised advertisements.

According to Latour (1990) and Lass and Hart (2010), male audiences tend to be more accepting of stereotypical roles, such as female nudity, in advertisements than female audiences. Wyllie et al. (2015) found that women respond more positively to mild-sexual stimuli than explicit sexual stimuli featuring nudity or sexual acts. This research shows that there are no significant differences between male and female participants in terms of preference or gaze behaviour.

Despite the evolving attitudes towards gender roles, some research still suggests that sexualised images in advertising can produce positive outcomes, influencing consumer behaviour (Furnham & Mainaud, 2011; Leka et al., 2013; King et al., 2015; Wirtz et al., 2017). Our results do not confirm this, as non-sexual advertisements were preferred to sexual advertisements.

As a result of our study, sexual advertisements were not viewed for a longer time than non-sexual advertisements. Adding sexualised images to an advertisement will not ensure it is noticed faster.

Our study confirms the theoretical assumptions about the importance of studying the influence of gender stereotypes in advertising in general. In terms of the theoretical aspect, the novelty of our research is the study of the youth (student) audience, with the participation of subjects of different nationalities (culturally, mentally mixed composition of participants).

Our results support previous publications that reflect that non-sexual advertising is (generally) preferred and attractive regarding consumer attention. It should be noted that the conditions and participants in the experiment determine some of its limitations, which we have pointed out.

The results obtained have a direct practical application from the point of view of the expediency of using non-sexual advertising of perfumes. We consider it acceptable to extend these conclusions to similar products, particularly cosmetics and youth products for face and body care. For the category of consumers studied, using non-sexual advertising and related images is more attractive and appropriate.

When considering the possibility of a broader generalisation of the results obtained one should also consider the specifics of the product (in our case, perfumes). For several other goods (for example, cars, alcohol, and electronics), a different situation is possible. Also, the results may differ for homogeneous cultural groups, which is well reflected in the literature.

When managers decide to use sexual advertisements, they may put their brand image in a position to be harmed.

Sexual images in advertising can distract consumers, leading to unwanted gaze behaviour, negative attitudes, and unfavourable brand image (Cummins et al., 2021; Gong et al., 2021).

This suggests that advertisers should carefully consider the potential impact of sexual content on consumer perceptions and overall effectiveness. In light of the results of this study, there is less effect from sexualisation to making the advertisement eye-catching. When there is no apparent difference between an advertisement with a sexualized image and a non-sexual image, the risk of damaging a brand should be considered. Due to no apparent performance gain from being better noticed and risk of wrongful associations with the brand, non-sexual images should be preferred for advertisements.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This research looked at the differences in gaze behaviour and preference among young people with a modern view of gender stereotypes. Adding a control group into the sample who do not share this modern view could extend this research. Furthermore, our study tested the sample with one question to determine their view on stereotypes. Future research should use more questions to identify different views on gender stereotypes.

The authors used a small sample of 22 students, which limits the generalisation of the results, even though such a sample is not uncommon among eye-tracking studies. Increasing the sample size would provide more solid backing to the claims and their generalising capacity. This research can also be developed further if a specific homogeneous culture group is taken into focus. This can then be repeated in different groups for comparison.

The choice of advertisements can also influence the results. Different types of advertisements could be chosen for testing, which can vary in their level of sexualising, specific features of the models, and other possible variations.

While sexualising is a problematic issue in the advertising field of research, other important gender-based stereotypes could be addressed to see if they are still meaningful for captivating the attention of modern consumers and driving their preferences. Weight, roles of the profession, and used colours are a few examples of how this research could be extended to look at other stereotyping advertisements.

References

Adema, W. (2013). Greater gender equality: What role for family policy? Family Matters, 93, 7–16.

Afsari, Z., Keshava, A., Ossandón, J., & König, P. (2018). Interindividual differences among native right-to-left readers and native left-to-right readers during free viewing task. Visual Cognition, 26(6), 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506285.2018.1473542

Araüna, N., Dhaenens, F., & Bauwel. (2017). Historical, temporal and contemporary trends on gender and media. Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies, 9(2), 177–184. https://doi:10.1386/cjcs.9.2.177_7

Baxter, S., Kulczynski, A., & Ilicic, J. (2016). Ads aimed at dads: Exploring consumers’ reactions towards advertising that conforms and challenges traditional gender role ideologies. International Journal of Advertising, 35(6), 970–982. https://doi: 10.1080/02650487.2015.1077605

Crowley, A., Spangenberg, E., & Hughes, K. (1992). Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Attitudes Toward Product Categories. Marketing Letters, 3(3), 239–249.

Cummins, G. R., Gong, Z. H., & Reichert, T. (2021). The impact of visual sexual appeals on attention allocation within advertisements: An eye-tracking study. International Journal of Advertising, 40(5), 708–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1772656

Daechun, A., & Sanghoon, K. (2007). Relating Hofstede’s masculinity dimension to gender role portrayals in advertising: A cross-cultural comparison of web advertisements. International Marketing Review, 24(2), 181–207. https://doi:10.1108/02651330710741811

Davis, S., & Greenstein, T. (2009). Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 87–10.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 991–1004. https://doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.991

Eagly, A., & Karau, S. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Fidelis, B., Oliveira, J., Giraldi, J., & Santos, R. (2017). Sexual appeal in print media advertising: Effects on brand recall and fixation time. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel, 21(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/RJTA-12-2016-0033

Ford, J., & Latour, M. (1996). Contemporary Female Perspectives of Female Role Portrayals in Advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 18(1), 81.

Furnham, A., & Farragher, E. (2000). A Cross-Cultural Content Analysis of Sex-Role Stereotyping in Television Advertisements: A Comparison Between Great Britain and New Zealand. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(3), 415.

Furnham, A., & Mainaud, L. (2011). The Effect of French Television Sexual Program Content on the Recall of Sexual and Nonsexual Advertisements. Journal of Sex Research, 48(6), 590–598.

Gong, Z., Holiday, S., & Cummins, G. (2021). Can’t take my eyes off of the model: The impact of sexual appeal and product involvement on selective attention to advertisements. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 29(2), 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2020.1803089

Grau, S. L., & Zotos, Y. (2016). Gender stereotypes in advertising: A review of current research. International Journal of Advertising, 35(5), 761–770. https://doi:10.1080/02650487.2016.1203556

Grover, S., & Hundal, B. (2014). A Socio-cultural Examination of Gender Role: A Study of Projection of Women in Advertisements. Journal of Marketing & Communication, 9(3), 28–36.

Haines, E., Deaux, K., & Lofaro, N. (2016). The Times They are a-Changing … or Are They Not? A Comparison of Gender Stereotypes, 1983–2014. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 353–363. https://doi:10.1177/0361684316634081

Hernandez, M., Wang, Y., Sheng, H., Kalliny, M., & Minor, M. (2017). Escaping the corner of death? An eye-tracking study of reading direction influence on attention and memory. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2016-1710.

Hill, D. (2010, October 15). The 6 Secrets of Eye-Tracking. Marketing Daily. https://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/137686/the-6-secrets-of-eye-tracking.html

Hilton, J., & Hippel, W. (1996). Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 47(1), 237.

Hwang, M., Kwon, M., Lee, S., & Kim, C. (2020). A Study on the Visual Attention of Sexual Appeal Advertising Image Utilizing Eye Tracking. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society, 11(10), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2020.11.10.207

Kilbourne, J. (2001). Beauty....and the Beast of Advertising. New York: Longman.

King, J., McClelland, A., & Furnham, A. (2015). Sex Really Does Sell: The Recall of Sexual and Non-sexual Television Advertisements in Sexual and Non-sexual Programmes. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 210–216.

Kraines, M., Kelberer, L., & Wells, T. (2017). Sex differences in attention to disgust facial expressions. Cognition & Emotion, 31(8), 1692–1697. https://doi:10.1080/02699931.2016.1244044

Langlois, J., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 390–423. https://doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390

Lass, P., & Hart, S. (2010). National Cultures, Values and Lifestyles Influencing Consumers Perception towards Sexual Imagery in Alcohol Advertising: An Exploratory Study in the UK, Germany, and Italy. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(5–6), 607–623. https://doi:10.1362/0267257041323936

Latour, M. (1990). Female nudity in print advertising: An analysis of gender differences in arousal and Ad response. Psychology and Marketing, 7(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220070106

Leka, J., McClelland, A., & Furnham, A. (2013). Memory for Sexual and Nonsexual Television Commercials as a Function of Viewing Context and Viewer Gender. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 584–592.

Lull, R., & Bushman, B. (2015). Do Sex and Violence Sell? A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Sexual and Violent Media and Ad Content on Memory, Attitudes, and Buying Intentions. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 1022–1048.

Matthes, J., Prieler, M., & Adam, K. (2016). Gender-Role Portrayals in Television Advertising Across the Globe. Sex Roles, 75(7–8), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0617-y

Milner, L., & Collins, J. (2000). Sex-Role Portrayals and the Gender of Nations. Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 67–79.

Myers, S., Deitz, G., Huhmann, B., Jha, S., & Tatara, J. (2020). An eye-tracking study of attention to brand-identifying content and recall of taboo advertising. Journal of Business Research, 111(C), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.009

Outing, S., & Ruel, L. (2004). The best of eyetrack III: What we saw when we looked through their eyes. Published on Poynter Institute (not dated). https://www.academia.edu/546755/The_best_of_eyetrack_III_What_we_saw_when_we_looked_through_their_eyes

Pavel, C. (2014). Stereotypes in Advertising. Quality – Access to Success, 15, 258–264.

Pilelienė, L., & Grigaliūnaitė, V. (2016). Effect of Visual Advertising Complexity on Consumers’ Attention. International Journal of Management, Accounting & Economics, 3(8), 489–501.

Plakoyiannaki, E., & Zotos, Y. (2009). Female role stereotypes in print advertising: Identifying associations with magazine and product categories. European Journal of Marketing, 43(11–12), 1411–1434. https://doi:10.1108/03090560910989966

Plakoyiannaki, E., Mathioudaki, K., Dimitratos, P., & Zotos, Y. (2008). Images of Women in Online Advertisements of Global Products: Does Sexism Exist? Journal of Business Ethics, 83(1), 101–112. https://doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9651-6

Pollay, R., & Gallagher, K. (1990). Advertising and cultural values: Reflections in the distorted mirror. International Journal of Advertising, 9(4), 359–372.

Reichert, T., & Carpenter, C. (2004). An update on sex in magazine advertising: 1983 to 2003. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 823–837.

Rupp, H., & Wallen, K. (2007). Sex differences in viewing sexual stimuli: An eye-tracking study in men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 51(4), 524–533. https://doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.008

Šula, T., Banyár, M., & Jur̂íková, M. (2017). Eye tracking measuring of visual perception of erotic appeals in the content of printed advertising communications and analysis of their impact on consumers. In A. Kavoura, D. P. Sakas & P. Tomaras (Eds.), Strategic Innovative Marketing (pp. 189–195). Springer.

Tartaglia, S., & Rollero, C. (2015). Gender Stereotyping in Newspaper Advertisements. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46, 1103–1109. https://doi:10.1177/0022022115597068

Wirtz, J., Sparks, J., & Zimbres, T. (2017). The effect of exposure to sexual appeals in advertisements on memory, attitude, and purchase intention: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Advertising, 37(2), 168–198.

Wyllie, J., Carlson, J., & Rosenberger, P. (2015). Does Sexual-Stimuli Intensity and Sexual Self-Schema Influence Female Consumers’ Reactions toward Sexualised Advertising? An Australian Perspective. Australasian Marketing Journal, 23(3), 188–195. https://doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2015.06.004

Yoon Min, H., & Kun Chang, L. (2018). Using an Eye-Tracking Approach to Explore Gender Differences in Visual Attention and Shopping Attitudes in an Online Shopping Environment. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 34(1), 15–24. https://doi:10.1080/10447318.2017.1314611

Appendix A

Stereotypical Ads and Non-Stereotypical Ads (Female Models)

Source: Pinterest

Appendix B

Stereotypical Ads and Non-Stereotypical Ads (Male Models)

Source: Pinterest