Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2022, vol. 13, no. 2(26), pp. 317–335 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2022.13.82

Strategic Partnership between SME Retailers and Modern Suppliers in Indonesia: A Relationship Marketing Approach

Anton Agus Setyawan (corresponding author)

Muhammadiyah University of Surakata, Indonesia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9664-7818

anton.setyawan@ums.ac.id

Fairuz Mudhofar

Muhammadiyah University of Surakata, Indonesia

fairusm1999@gmail.com

Yasinta Arum

Muhammadiyah University of Surakata, Indonesia

asintaarum@gmail.com

Ihwan Susila

Muhammadiyah University of Surakata, Indonesia

ihwan.susila@ums.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0925-4547

Moechammad Nasir

Muhammadiyah University of Surakata, Indonesia

moechammad.nasir@ums.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6509-2733

Abstract. This study aimed to analyze the business marketing relationship between modern suppliers and SME retailers to empower and strengthen SMEs in Indonesia. The theoretical framework is the relationship marketing model developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994). This framework is based on trust and commitment as the two key mediating variables. The study surveyed 250 SME retailers as respondents selected using purposive sampling. Furthermore, hypotheses were tested using path analysis. The findings showed that trust and commitment to business partnerships mediate the effect of influence strategy on loyalty to business partners and economic performance. The influence strategy significantly affects the business performance of the involved parties. Therefore, strategic business partnerships with modern suppliers improve SME retailers’ business performance.

Keywords: strategic partnership, influence strategy, trust, commitment, loyalty

Received: 1/12/2021. Accepted: 2/11/2022

Copyright © 2022 Anton Setyawan, Fairuz Mudhofar, Yasinta Arum, Ihwan Susila, Moechammad Nasir. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

A partnership between companies is a strategy to increase competition, product value, and business performance (Ejdys, 2018; Butaney & Wortzel, 1988; Tokman et al., 2019). It provides strategic advantages for the involved parties. The partnership between large enterprises is profitable due to the absence of gaps in size, technology, and resources. However, issues arise between large enterprises and SMEs because it possibly causes positive or negative impacts (Butaney & Wortzel, 1988; Keysuk, 2000). Maloni and Benton (2000) stated that power asymmetry determines the success or failure of business relationships between large enterprises and SMEs. Furthermore, Nyaga et al. (2013) suggested that power asymmetry plays a key role in the strategic advantages enterprises gain in a business relationship. The study also stated that power asymmetry could be disadvantageous for SMEs.

Hingley (2005) investigated the food industry supply channel involving large businesses and SMEs in the UK. The study found that the power asymmetry between the involved parties influenced the quality of a business relationship, but not negatively. Building understanding and communication helps anticipate the adverse impacts of power asymmetry between large enterprises and SMEs. For instance, the subcontracting partnership adversely affects several clusters of the furniture and wood sector SMEs in Central Java, Indonesia. SMEs lack technology support for developing product innovation, while business processes greatly depend on large enterprises (Setyawan et al., 2015). The partnership between exporters and craftsmen involves exporters providing raw materials, product designs, technical assistance, and market channels. Therefore, SMEs could not develop into efficient and well-performing business units.

Setyawan et al. (2014) examined the business relationship between large multinational enterprises and SME retailers in Yogyakarta, Semarang, and Surakarta. The study suggested that multinational enterprises gain long-term benefits under the agency partnership scheme. In contrast, SME retailers only gain a short-term benefit without clarity on the partnership sustainability. The study also found that SME retailers accepted these conditions as the only way to gain profitable business. Conversely, Ejdys (2018) found that the business relationship between large enterprises and SMEs improves performance significantly for both parties. Tokman et al. (2019) stated that trust, commitment, power, and social bonds contribute to a successful partnership.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) suggested that the marketing framework is feasible for analyzing business relationships between enterprises. The study tested this model on the automotive industry in the US and found that the key variables in business networks are commitment, trust, and power.

Business-to-business (B2B) marketing studies examine the relationships relevant to partnerships between enterprises. The two dominant concepts in a business relationship are transaction cost and relationship marketing. The transaction cost concept assumes that parties in a business relationship have two weaknesses, including opportunism and bounded rationality. Therefore, rules and supervision are required to balance the benefits of both parties (Buvik, 2001). Powell (2004) stated that contractual arrangements that regulate penalties and incentives for the involved parties should be devised to evade harm in a business relationship.

The relationship marketing concept is implemented in the business relationship between enterprises. Within this concept, the core of the business relationship is trust in partners and commitment to business relationships (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Ramaseshan et al., 2006). It is a long-term business relationship between enterprises that benefits both parties (Hingley, 2005). Trust and commitment are major components in relationship marketing, resulting in business relationship satisfaction, loyalty to business partners, and fine business performance (Grewal et al., 2019). According to Haque and Rana (2019), relationship marketing promotes convenience by accommodating both parties’ interests.

There are two gaps related to B2B studies in the context of SME retailers. The first gap relates to implementing relationship marketing to analyze partnerships between large enterprises and SME retailers in Indonesia. The relationship marketing theory is based on trust and commitment as mediating variables. This theory was examined to unveil its feasibility as the framework for strategic partnerships between large enterprises (suppliers) and SME retailers. The second gap relates to the SME retailers’ strategic partnership. Retailers expect strategic partnerships to improve business performance, as indicated by higher sales, profits, and business growth. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the effect of influence strategies, trust in business partners, and commitment to partnerships on SME retailers’ business performance.

This study investigated business partnerships between large enterprises and SME retailers in Solo Raya, Central Java, Indonesia. Relationship Marketing was employed as a theoretical framework with four variables, including influence strategies, trust, commitment, and business performance. Influence strategy, or power, is how an organization controls its partners to fulfil strategic goals (Maloni & Benton, 2000). It is a reciprocal act of companies involved in a business relationship (Hingley, 2005). Furthermore, influence strategy (or power) is an independent variable that affects trust and commitment (Ramaseshan et al., 2006). Maloni and Benton (2000) used the term power instead of influence strategy, though their conceptual definitions are similar. The two types of power based on their source are coercive and non-coercive power (Maloni & Benton, 2000). According to Kim (2000), companies in business relationships use non-coercive power to control and evaluate their partners. Therefore, this study proposed that the influence strategy of large companies as suppliers changes the performance of SME retailers.

This study developed a theoretical model of relationship marketing based on Morgan and Hunt (1994), which found that power is a dependent variable affecting business relationships in the US automotive industry. Morgan and Hunt (1994) also identified trust and commitment as two key mediating variables in relationship marketing. Moreover, Kim (2000) proposed the role of power as a tool for companies to influence business partners to fulfil their common goals. According to Chen et al. (2011), influence strategy is an antecedent of trust, commitment, and business performance in a relationship between companies. This study adopted the concept of power as an influence strategy exercised by large companies toward SME retailers.

Trust and commitment are key mediating variables in Relationship Marketing Theory (Morgan & Hunt,1994). This study proposed that the two mediating variables are critical in assessing the effect of the influence strategy on SME retailers’ business performance. SME business performance should be measured with an easier method because the business processes are simple (Blackburn et al., 2013; Begonja et al., 2016). This study analyzed the impact of large company suppliers’ influence strategy on SME retailers’ business performance. It also proposed trust in business partners and commitment to business relationships. They are the modifications of two original constructs of trust and commitment developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994) in their relationship marketing theory. Furthermore, a theoretical framework was developed to analyze the strategic relationship between large companies and SME retailers. The results are expected to enrich relationship marketing theory, especially in B2B marketing.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

2.1 Relationship Marketing and Business Partnerships

Gulati et al. (2000) identified five key issues in the studies related to strategic networks. The issues are industry structure, positioning within an industry, inimitable firm resources and capabilities, contracting and coordination costs, as well as dynamic network constraints and benefits. The strategic partnership between large companies and SMEs encompasses contracting and coordination costs, as well as dynamic network constraints and benefits. Uzzi (1997) found that embeddedness plays an important role in the business relationship. Embeddedness is the strategic partnership between two companies, according to relationship marketing (Gummerus et al., 2017). According to Morgan and Hunt (1994), relationship marketing comprises establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relational exchanges. It was defined by Gronroos (1994) as a marketing activity to establish, foster, and maintain relationships with consumers and business partners as a mutually beneficial relationship to sustain the interests of both parties. Some basic elements of relationship marketing include:

1. Commitment – Enterprises that fulfil their commitment achieve customer satisfaction, repurchase intention, and long-term financial benefits.

2. Trust – Chen (2011) defined trust as a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence. It requires confidence to trust the partner due to their expertise, consistency, and intention. Furthermore, trust is an intentional behavior reflecting reliance on partners and involves uncertainty and vulnerability of the trusted party.

The concept of relationship marketing is a result of the transitional process from the traditional buyer-seller into a more strategic business relationship. Spekman and Carraway (2006) discussed the transitional process and suggested several prerequisite factors, which became the theoretical basis for relationship marketing.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) developed a relationship marketing model by proposing trust and commitment as two key mediating variables. The model was tested in the automotive industry and its business network in the United States. Therefore, this study used trust in business partners and commitment to business relationships as the key mediating variables. It aimed to analyze the business relationship between SMEs as retailers and large enterprises as suppliers.

2.2 Influence Strategy and Relationship Marketing

Power is the ability to influence others (Ramaseshan et al., 2006; Kim, 2000; Butaney & Wortzel, 1988). It is also known as the influence strategy in inter-firm relationships (Maloni & Benton, 2000). Furthermore, power is divided into coercive and non-coercive (Ramaseshan et al., 2006). Coercive power is the company’s ability to control and sanction business partners when they violate the business agreement. Non-coercive power is the company’s ability to reward business partners when they improve performance related to their partnership (Zemanek & Pride, 1996). According to Ramaseshan et al. (2006), department stores use coercive power by putting pressure on tenants to achieve certain behaviors. There might be penalties when the tenants fail to comply with these rules. Coercive power is commonly used in advertising campaigns, customer service levels, or store opening hours.

Influence strategy in the business relationship between modern enterprises as suppliers and SME retailers relates to a party’s ability to influence the decisions of another party. It is reflected in the supplier’s ability to determine the highest retail price of products distributed to SME retailers. Alternatively, the influence strategy limits the number of products distributed to retailers to ensure even distribution. SME retailers could influence the suppliers by requesting a discount for cash purchases or bonuses for certain sales amounts.

The influence strategy positively impacts the enterprise’s satisfaction with the business relationship. Terawatanavong et al. (2007) stated that a profitable business relationship results from satisfaction. Therefore, influence strategies using non-coercive and non-conflict approaches are preferred to maintain relationship satisfaction (Kim, 1998).

Regarding relationship marketing, Morgan and Hunt (1994) stated that influence strategies impact the trust in business partners and the commitment to business relationships. Wu et al. (2004) explicated that trust, influence strategy, and duration of business relationships are associated with the commitment to maintain long-lasting and mutually beneficial business relationships.

H1 Influence strategy positively affects business relationship satisfaction.

H2 Influence strategy positively affects trust in business partners.

H3 Influence strategy positively affects commitment to business relationships.

H4 Business relationship satisfaction positively affects trust in business partners.

H5 Business relationship satisfaction positively affects commitment to business relationships.

2.3 Relationship Marketing, Loyalty to Business Partners, and Business Performance

Studies on customer behavior show that commitment is a construct of customer loyalty (Wood, 2002). Commitment is a component of relationship marketing and ensures a long-term customer relationship (Cooper et al., 2005). This construct is useful for explaining relationship marketing, where customers committed to a specific brand are more likely to be loyal.

The concept of continuance commitment has been introduced recently as a form of commitment. Continuance commitment is a bond between two organizations for long-term economic benefits or cost efficiency (Wu et al., 2012). It is rooted in the scarcity of alternatives and switching costs (Wong et al., 2008). In B2B marketing, a customer with a continuance commitment would unlikely switch to other business partners because it is costly and has rare alternatives (Sahadev, 2008). A business relationship has economic benefits, making it costly to switch partners (Sahadev, 2008). Therefore, continuance commitment is an appropriate construct to measure commitment to business relationships between enterprises.

Spekman and Carraway (2006) and Gronroos (1994) found that trust is the basic component of relationship marketing. Trust implies the expectations of the parties in a transaction and the risks associated with assuming and acting on such expectations (Ramaseshan et al., 2006). Discussion about trust is linked to relationship marketing (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Haque & Rana, 2019). Additionally, trust and commitment are integral to relationship marketing (Ekelund & Sharma, 2001).

The outcome of a business relationship within the relationship marketing model is loyalty to partners. Ramaseshan et al. (2006) examined the impact of relationship marketing on retailers’ loyalty in the retail industry in China. The study showed that relationship marketing strategies positively affect retailers’ loyalty to their suppliers. Therefore, trust and commitment are key mediating variables in this study. Wu et al. (2012) analyzed the role of trust and commitment in the supply chain partners of the high-tech industry in Taiwan. The study corroborated the role of relationship marketing as a mediating variable of loyalty to business partners.

Companies have business partnerships to improve their performance or competitive advantage, a valuable tool to win a business competition. A relationship marketing-based business relationship has several advantages, including improved economic performance (Corsten & Kumar, 2005; Johnson, 1999) and strategic performance (Ramaseshan et al., 2006). Business relationships based on trust and commitment improve economic and strategic performance (Mas-Ruiz, 2000). According to Corsten and Kumar (2005), the economic performance parameters affected by relationship marketing are sales, growth, profits, and company size.

H6 Business relationship satisfaction positively affects loyalty to business partners.

H7 Business relationship satisfaction positively affects business performance.

H8 Trust in business partners affects loyalty to business partners.

H9 Trust in business partners affects business performance.

H10 Commitment to business relationships positively affects loyalty to business partners.

H11 Commitment to business relationships positively affects business performance.

3. Research Method

3.1 Conceptual Framework

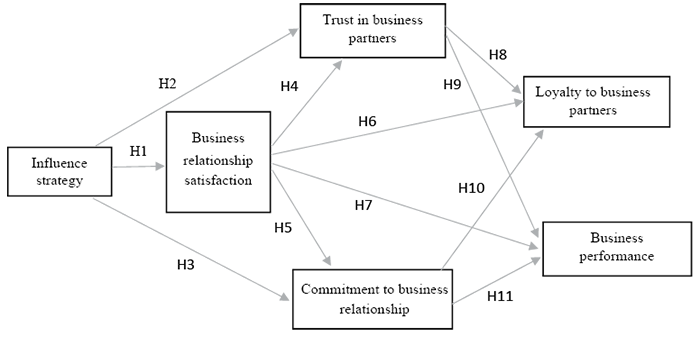

The study model explains the relationship between the constructs. The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Conceptual Framework of SME Retailers Partnership

3.2 Population and Sample

The study population comprised SME retailers and grocery stores engaged in the distribution channels of foods and agricultural products. The sample consisted of SME retailers and grocery stores in Solo Raya selected using purposive and quota sampling methods with the following criteria:

1. SME retailers are not affiliated with any national or international franchise.

2. SME retailers are engaged in food commodities and agricultural products.

3. They have more than five years of experience in the business.

Regarding the sample size, 250 SME retailers were initially targeted as the respondents. This relates to the spread of SME retailers in food commodities and agricultural products in the Solo Raya area, Central Java Province, Indonesia. The respondents are concentrated in five local markets, including Pasar Legi and Pasar Nusukan in Surakarta, Pasar Bunder in Sragen, Pasar Sunggingan in Boyolali and Pasar Tawangmangu in Karanganyar. In each local market, a quota of 50 SME retailers was taken according to the sample criteria, resulting in 250 respondents. The number of respondents was based on the multivariate data analysis that requires 250–500 respondents to obtain a stable beta coefficient (Hair et al., 2010).

3.3 Operational Definition and Variable Measurement

Table 1 summarizes the operational definition and variable measurement.

Table 1

Variable Measurement Dimensions

|

No |

Variable |

Measurement Dimension |

Sources |

|

1. |

Influence Strategy |

Control toward quality, price, and discount Payment delay Sanction and penalty |

Ramaseshan et al. (2006); Kim (2000), Maloni and Benton (2000) |

|

2. |

Commitment to Business Relationships |

Business relationship duration Proximity level Switching costs Partner alternatives |

Wu et al. (2004); Srinivasan and Moorman (2005) |

|

3. |

Satisfaction with Business Relationships |

Positive perception towards the benefits of business relationships Positive perception toward the decisions of business partners |

Gaski and Nevin (1985); Terawatanavong et al. (2007) |

|

4. |

Trust in Business Partners |

Commitment to business partners Communicative regarding policy changes Consistency and honesty in a business relationship |

Wu et al. (2004); Kim (2000); Ryu et al. (2008) |

|

5. |

Loyalty to Business Partners |

Business relationship duration The intensity of business transaction Reference for other parties about partner’s quality |

Rauyruen and Miller (2007); Hallowell (1996); Dharmmesta (1999) |

|

6. |

Business Performance |

Sales growth Profit growth Market share Overall benefits |

Mas-Ruiz (2000); Kim (2000); Corsten and Kumar (2005); Ramaseshan et al. (2006); Neill and Rose (2006); Hallowel (1996) |

The estimation model involves the following equations:

1. Business relationship satisfaction = a11 + b11 Influence strategy + e11

2. Trust in business partners = a21 + b22 Influence strategy + e23

3. Commitment to business relationship = a31 + b32 Influence strategy + e33

4. Trust in business partners = a41 + b42 Business relationship satisfaction + e43

5. Commitment to business relationship = a51 + b52 Business relationship satisfaction + e53

6. Loyalty in business partners = a61 + b62 Trust in business partners + b63 Business relationship satisfaction + b64 Commitment to business relationship + e65

7. Business performance = = a71 + b72 Trust in business partners + b73 Business relationship satisfaction + b74 Commitment to business relationship + e75

These equations were simultaneously estimated using path analysis.

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1 Validity and Reliability Testing

Table 2 illustrates the validity testing result using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The study adopted Hair et al. (2010) criteria of validity, where the construct indicator is valid when the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.5. Subsequently, Cronbach’s Alpha was used to assess the constructs’ reliability. The constructs are considered reliable with a minimum value of 0.6 (Neuman, 2000).

Table 2

The Result of Validity Testing of the Study Instrument

|

Indicator |

Factor Loadings |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

Influence Strategy |

||||||

|

1. Suppliers have the ability to control the price of the product. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.681 |

|

2. Suppliers provide advice concerning product quality. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.644 |

|

3. Unpleasant services are received when the supplier’s advice is disregarded. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.759 |

|

4. Retailers are seriously warned when they refuse their supplier’s advice. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.784 |

|

5. Retailers experience payment delays when they disregard their supplier’s advice. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.641 |

|

6. Retailers receive pleasant services when they follow their supplier’s advice and suggestions. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.732 |

|

7. Retailers gain more benefits when they follow their supplier’s advice and suggestions. |

|

|

|

|

|

0.676 |

|

Business Relationship Satisfaction |

||||||

|

1. Retailers are satisfied with their supplier’s services. |

|

|

|

|

0.662 |

|

|

2. Suppliers provide satisfactory assistance. |

|

|

|

|

0.783 |

|

|

3. Retailers are satisfied with their business interaction with suppliers. |

|

|

|

|

0.724 |

|

|

4. Suppliers understand what retailers need. |

|

|

|

|

0.796 |

|

|

5. Overall, retailers are satisfied with their suppliers. |

|

|

|

|

0.659 |

|

|

Trust in Business Partner |

||||||

|

1. Suppliers are honest. |

|

|

|

0.472 |

|

|

|

2. Suppliers are supportive. |

|

|

|

0.818 |

|

|

|

3. Our suppliers are trustworthy. |

|

|

|

0.608 |

|

|

|

4. Suppliers always make decisions that benefit retailers. |

|

|

|

0.723 |

|

|

|

Commitment to Business Relationships |

||||||

|

1. Retailers maintain a profitable business relationship with suppliers. |

0.546 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Retailers have difficulties switching to other suppliers. |

0.814 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Retailers maintain suppliers at a reasonable cost. |

0.631 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Retailers have limited alternatives for suppliers. |

0.737 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loyalty to Business Partner |

||||||

|

1. Retailers have no intention of switching suppliers. |

|

|

0.566 |

|

|

|

|

2. Retailers keep their business partnerships with current suppliers. |

|

|

0.703 |

|

|

|

|

3. Retailers entrust all business matters to their suppliers according to the arrangements. |

|

|

0.754 |

|

|

|

|

4. Retailers promote the quality of business partners to other enterprises. |

|

|

0.660 |

|

|

|

|

Business Performance |

||||||

|

1. Retailers have achieved higher sales since initiating the current suppliers. |

|

0.782 |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Retailers have achieved company growth since initiating the current suppliers. |

|

0.782 |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Retailers have achieved higher market share since initiating the current suppliers. |

|

0.806 |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Retailers have achieved higher profits since initiating the current suppliers. |

|

0.759 |

|

|

|

|

The validity test results showed that trust in business partners has factor loading less than 0.5, namely “Our suppliers are honest.” Nevertheless, this question was not omitted because a factor loading of 0.472 is still acceptable (Nunnally, 1978). It is essential to inform the business partner’s honesty, establishing trust.

Table 3 presents the reliability test results using Cronbach’s Alpha. According to Hair et al. (2010), the minimum value for Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.6, meaning that the construct with a coefficient less than 0.6 has low reliability.

The reliability test showed that the study instrument has a low Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The value of loyalty to business partners, commitment to business relationships, and trust in business partners slightly exceeds the minimum criterion of 0.6.

Table 3

The Results of Reliability Testing

|

Construct |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Status |

|

Business relationship satisfaction |

0.778 |

Reliable |

|

Loyalty to business partners |

0.606 |

Reliable |

|

Commitment to business relationship |

0.625 |

Reliable |

|

Trust in business partners |

0.624 |

Reliable |

|

Influence strategy |

0.828 |

Reliable |

|

Business performance |

0.789 |

Reliable |

4.2 Hypothesis Testing

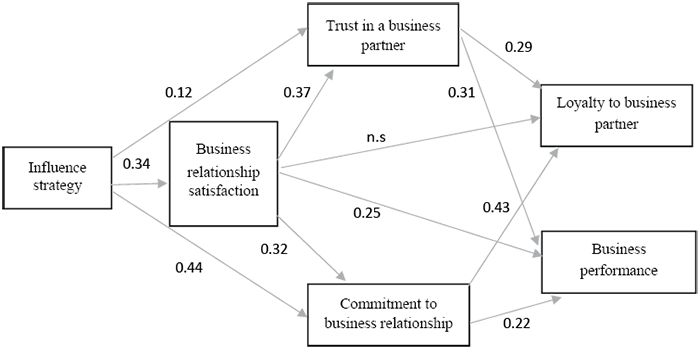

Hypotheses were tested using path analysis on the relationship between constructs that simultaneously examine two mediating variables of commitment to business relationships and trust in business partners. However, the analysis focused on the relationship between constructs to explain strategic partnerships between SME retailers and large enterprises. Figure 2 shows a strategic partnership model between SME retailers and large enterprises.

Figure 2

Empirical Model of SME Retailers’ Strategic Partnership

Figure 2 shows the empirical model of a strategic partnership with each regression coefficient. Table 4 summarizes the path analysis with the critical ratio of each regression coefficient.

Table 4

The Path Analysis Results

|

Path Analysis |

Regression |

Critical |

P-value |

Status |

|

Influence strategy → Business relationship satisfaction |

0.338 |

6.918 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Influence strategy → Trust in the business partner |

0.123 |

2.844 |

0.004 |

Significant |

|

Influence strategy → Commitment to business relationship |

0.440 |

9.328 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Business relationship satisfaction → Trust in the business partner |

0.372 |

7.181 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Business relationship satisfaction → Commitment to business relationship |

0.324 |

5.741 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Business relationship satisfaction → Loyalty to business partner |

0.122 |

1.574 |

0.115 |

Not significant |

|

Business relationship satisfaction → Business performance |

0.256 |

3.602 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Trust in business partners → Loyalty to business partner |

0.294 |

3.615 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Trust in business partners → Business performance |

0.308 |

4.114 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Commitment to business relationship → Loyalty to business partner |

0.426 |

6.521 |

0.000 |

Significant |

|

Commitment to business relationship → Business performance |

0.225 |

3.749 |

0.000 |

Significant |

Table 5

The Goodness of Fit of SME Strategic Partnership Model

|

Goodness of Fit |

Cut Off Value |

Estimation Result |

Status |

|

Chi-Square |

Expectedly low |

17.467 |

Good |

|

Probability |

≥ 0.05 |

0.002 |

Good |

|

GFI |

≥ 0.90 |

0.977 |

Good |

|

AGFI |

≥ 0.90 |

0.878 |

Moderate |

|

CFI |

≥ 0.95 |

0.971 |

Good |

|

RMSEA |

≤ 0.08 |

0.117 |

Good |

|

CMIN/DF |

≤ 2.00 |

4.367 |

Good |

Table 4 illustrates the relationship between constructs in the SME retailers–large enterprises partnership model. The path analysis showed that the influence strategy implemented by large enterprises toward SME retailers positively and significantly affects business relationship satisfaction, trust in business partners, and commitment to business relationships. This is indicated by the critical ratio values of 6.918, 2.844, and 9.328, respectively. Meanwhile, business relationship satisfaction positively and significantly affects trust in a business partner, commitment to business relationship, and retailer’s business performance. It is indicated by the critical ratio values of 7.181, 5.741, and 3.602, respectively. This implies that customer satisfaction mediates the effect of influence strategy on trust in a business partner, commitment to business relationships, and business performance. Business relationship satisfaction insignificantly affects loyalty to business partners (CR = 1.574). This means that business relationship satisfaction does not mediate the effect of influence strategy on loyalty to a business partner.

Trust in business partners positively and significantly affects loyalty to business partners and business performance, as indicated by the critical ratio values of 3.615 and 4.114, respectively. Therefore, trust in business partners mediates the effect of influence strategy and business relationship satisfaction on loyalty to business partners and business performance.

Commitment to business relationships positively and significantly affects loyalty to business partners and business performance, as shown by the critical ratio values of 6.521 and 3.749, respectively. This means that commitment to business relationships mediates the effect of influence strategy and business relationship satisfaction on loyalty to business partners and business performance.

The goodness of fit showed that the study model fits the data well. From the six criteria for the goodness of fit, only the adjusted goodness of fit index/AGFI is moderate, while the other five were good. This means the model is a good-fitting model theoretically and empirically. The model was devised based on the conceptual framework of relationship marketing. Moreover, the relationship marketing model constructs include satisfaction, commitment, and trust. In this case, commitment and trust are the key mediating variables in relationship marketing.

4.3 Discussion

This study corroborates the relationship marketing model developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994) that commitment and trust mediate between influence strategy and business performance. Morgan and Hunt (1994) tested this model on the business channels of the automotive industry in the US and found similar results to this study. Regarding the use of influence strategy in business relationships between enterprises, this study showed different results from Morgan and Hunt (1994). According to Morgan and Hunt (1994), the influence strategy of enterprises with greater power negatively impacts their partners’ business performance. This study found that large enterprises with greater power positively impact the business performance of SME partners. Maloni and Benton (2000) found that power is the core of influence strategy that positively or negatively affects a business partnership. An example of an adverse effect is exploitation, while constructive influence strategy leads to strategic business partnerships (Nyaga et al., 2013). Large enterprises practice influence strategy by offering discounts to SME retailers that sell products beyond sales targets.

Satisfaction in a business partnership is crucial in sustaining the partnership quality. Regarding the business relationship between SME retailers and large suppliers, satisfaction involves the policies related to products and prices. These policies include discounts for a specific amount of purchase, priority for specific products, and a goods return policy. Terawatanavong et al. (2007) reaffirmed that business partnership satisfaction is a strategic element in the sustainability of a long-term and profitable business relationship.

This study found that trust in business partners and commitment to a business relationship are the key mediating variables (KMV) that relate to the influence of strategy and business performance. The finding supports Morgan and Hunt (1994) preliminary study on relationship marketing in a business-to-business setting. Moreover, this study found that SME retailers tend to trust large businesses or suppliers as their business partners. They perceive that large suppliers greatly notice their interests because they spearhead the distribution process to the final customers. Moreover, SME retailers perceive that large suppliers determine their business policies by considering their interests.

SME retailers have a continuance commitment or a long-term attachment to a business relationship due to economic factors (Ramaseshan et al., 2006). Regarding business partnerships between large suppliers and SME retailers, the commitment to business relationships occurs due to two factors. First, the large suppliers commit to the business relationship due to reasonable costs for maintaining the relationship with SME retailers. Second, SME retailers commit to the business relationship because it is costly to switch business partners.

The loyalty to a business partner in a strategic partnership involves the SME retailers’ willingness to repurchase from large suppliers. Customer behavior in B2B relates to the volume and purchase frequency instead of reference (Spekman & Carraway, 2006). Traditional retailers are relatively loyal to their suppliers since they have a positive perception toward them. This positivity results from trust in business partners and commitment to a strategic partnership.

The influence strategy used by large suppliers toward SME retailers positively affects business relationship satisfaction, trust in a business partner, and commitment to business relationships. The SME retailers’ commitment to business relationships and trust in business partners improve business performance. Retailers claim to obtain higher sales, company growth, and profits due to strategic partnerships with large suppliers. This finding supports Haque and Rana (2019) on business performance improvement due to strategic partnership.

5. Conclusion

The analysis showed that a strategic partnership improves SME retailers’ business performance. This study also found that the influence strategy used by large suppliers positively affects the SME retailer’s business relationship satisfaction, commitment to business relationships, and trust in business partners. Large suppliers constantly encourage SME retailers to improve performance by providing incentives, discounts, bonuses, and excellent services. Furthermore, they benefit from the performance of SME retailers. Large enterprises with many SME retailers also experience business growth in sales, market share, profits, and company size.

This study only examined SME retailers’ perceptions and not the perceptions of both parties. In relationship marketing studies, this is known as the non-dyadic approach. Therefore, the influence strategy was examined based on the perception of one party. The strategy was generalized instead of being classified as coercive and non-coercive. Classification is essential to identify the strategy employed by the involved parties in a business relationship.

This study is expected to contribute to developing B2B relationship marketing. It verified that influence strategy emerges due to power asymmetry in capital, technology, organizational management and human resources, and positively impacts SME partners. However, the power asymmetry between large enterprises and SMEs in strategic partnerships benefits both parties.

Large enterprises and SMEs should optimize and make their business relationships more strategic. Both parties must maintain trust in business partners and commitment to business relationships. In devising business strategies, they must recognize the interest of business partners and realize that it should be a long-term partnership.

This study is also expected to contribute to the policy-making on SME development. It emphasized the advantages of strategic partnerships between large enterprises and SMEs. Large enterprises have the capacity to support and encourage SMEs to improve their business performance through a mutually beneficial strategic partnership.

References

Begonja, M., Čićek, F., Balboni, B., & Gerbin, A. (2016). Innovation and Business Performance Determinants of SMEs in the Adriatic Region that Introduced Social Innovation. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 1136-1149. DOI: 10.1080/1331677X.2016.1213651

Blackburn, R. A., Hart, M., & Wainwright, T. (2013). Small Business Performance: Business, Strategy and Owner-Manager Characteristics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 8–27. DOI 10.1108/14626001311298394

Butaney, G., & Wortzel, L. H. (1988). Distributor Power versus Manufacturer Power: The Customer Role. Journal of Marketing, 52, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251685

Buvik, A. (2001). The industrial purchasing research framework: A comparison of theoretical perspectives from microeconomics, marketing and organization science. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 16 (6), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/eum0000000006019

Chen, J. V., Yen, D.C., Rajkumar, T. M., & Tomochko, N. A. (2011). The Antecedent Factors on Trust and Commitment in Supply Chain Relationships. Computer Standards & Interface, 33(3), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2010.05.003

Cooper, D. P., & Schindler, P. S. (2014). Business Research Methods (12th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Cooper, M. J., Upton, N., & Seaman, S. (2005). Customer Relationship Management: A Comparative Analysis of Family and Non-family Business Practices. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627x.2005.00136.x

Corsten, D., & Kumar, N. (2005). Do Suppliers Benefit from Collaborative Relationships with Large Retailers? An Empirical Investigation of Efficient Consumer Response Adoption. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.3.80.66360

Ejdys, J. (2018). Building Technology Trust in ICT Application at a University. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(5), 980–997. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijoem-07-2017-0234

Ekelund, C., & Sharma, D. D. (2001). The Impact of Trust on Relationship Commitment: A Study of Standardized Products in a Mature Industrial Market. [Unpublished Research Report].

Grewal, R., Lilien, G. L., Bharadwaj, S., Jindal, P., Kayande, U., Lusch, R.F., Mantrala, M., Palmatier, R. W., Rindfleisch, A., Scheer, L. K., Spekman, R., & Sridhar, S. (2019). Business-to-Business Buying: Challenges and Opportunities. Customer Needs and Solutions, 2(3), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-015-0040-5

Gronroos, C. (1994). From Marketing Mix To Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing. Management Decision, 32(2), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1320-1646(94)70275-6

Gulati, R., Nohria, N., & Zaheer. A. (2000). Strategic Networks. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(200003)21:3<203::aid-smj102>3.0.co;2-k

Gummerus, J., von Koskull, C., & Kowalkowski, C. (2017). Relationship marketing: Past, present, and future, Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2016-0424

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.) Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

Hingley, M. K. (2005). Power Imbalance in UK Agri-Food Supply Channels: Learning To Live With The Supermarkets? Journal of Marketing Management, 21(1-2), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257053166758

Hoque, I., & Rana, M. B. (2019). Buyer-Supplier Relationships From The Perspective of Working Environment and Organisational Performance: Review and Research Agenda. Management Review Quarterly, 70,1–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00159-4

Johnson, J. L. (1999). Strategic Integration in Industrial Distribution Channels: Managing The Interfirm Relationship as a Strategic Asset. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 27(1), 4–18. https://doi.or10g/10.1177/0092070399271001

Kim, K. (2000). On Interfirm Power, Channel Climate and Solidarity in Industrial Distributor-Supplier Dyads. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 28(3), 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300283007

Kim, Y. (1998). A study on marketing channel satisfaction in international markets. Logistics Information Management, 11(4), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/09576059810226785

Maloni, M., & Benton, W. C. (2000). Power Influences in The Supply Chain. Journal of Business Logistics, 21(1) 49–73.

Mas-Ruiz, F. J. (2000). The Supplier-Retailer Relationship in The Context of Strategic Groups. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 28(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550010315278

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The Commitment–Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

Neuman, W. L. (2000). Social Research Methods, Qualitative and Quantitative Methods (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon..

Ng, Kim-Soon, Abd Rahman Ahmad, Chan Wei Kiat, & Hairul Rizad Md Sapry. (2017). SMEs Are Embracing Innovation for Business Performance. Journal of Innovation Management in Small & Medium Enterprises, Vol. 2017, Article ID 824512. DOI: 10.5171/2017.824512

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). NY: McGraw Hill.

Nyaga, G. N., Lynch, D. F., Marshall, D., & Ambrose, E. (2013). Power Asymmetry, Adaptation and Collaboration in Dyadic Relationships Involving a Powerful Partner. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(3), 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12011

Powell, T. C. (2004). Strategy, Execution and Idle Rationality. Journal of Management Research, 4(2), 77–98.

Ramaseshan, B., Yip, L. C., & Pae, J. H. (2006). Power, Satisfaction and Relationship Commitment in Chinese Store-Tenant Relationship and Their Impact on Performance. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.11.004

Sahadev, S. (2008). Economic Satisfaction and Relationship Commitment in Channels: The Moderating Role of Environmental Uncertainty, Collaborative Communication and Coordination Strategy. European Journal of Marketing, 42(1/2), 178–195. DOI 10.1108/03090560810840961

Setyawan, A. A. Dharmmesta, B. S., Purwanto B.M., & Nugroho, S. S. (2014). Model of Relationship Marketing and Power Asymmetry in Indonesia Retail Industry. International Journal in Economics and Business Administration II(4), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.35808/ijeba/58

Setyawan, A. A., Isa, M., Wajdi, F. M., Syamsudin, & Nugroho, S. P. (2015). An Assessment of SME Competitiveness in Indonesia. Journal of Competitiveness, 7 (2), 60 – 74. DOI:10.7441/joc.joc.2015.02.04

Spekman, R. E., & Carraway, R. (2006). Making The Transition to Collaborative Buyer-Seller Relationship: An Emerging Framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.07.002

Terawatanavong, C., Whitwell, G. J., & Widing, R. E. (2007). Buyer satisfaction with relational exchange across the relationship lifecycle. European Journal of Marketing, 41(7/8), 915–938. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560710752456

Tokman, M., Mousa, F. T. & Dickson, D. (2019). The Link Between SMEs Alliance Portfolio Diversity and Top Management’s Entrepreneurial and Alliance Orientations. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16, 1001–1022.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00597-2

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(1), 35–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393808

Wong, Y. H., Chan, R.Y. K., Leung, T. K. P., & Pae, J. H. (2008). Commitment and vulnerability in B2B relationship selling in the Hong Kong institutional insurance service industry. Journal of Services Marketing, 22/2, 136–148. DOI 10.1108/08876040810862877

Wu, M., Weng, Y., & Huang, I. (2012). A Study of Supply Chain Partnerships Based On The Commitment–Trust Theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 24(4), 690–707. DOI 10.1108/13555851211259098.

Wu, W., Chiag, C., Wu, Y., & Tu, H. (2004). The Influencing Factors Of Commitment And Business Integration On Supply Chain Management. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 104(4), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570410530739

Zemanek, J. E., & Pride, W. M. (1996). Distinguishing Between Manufacturer Power and Manufacturer Salesperson Power. Journal Of Business & Industrial Marketing, 11(2), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858629610117143.