Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2020, vol. 11, no. 1(21), pp. 173–188 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2020.11.29

Value Chain and Economic Development: the Case of the Colombian Coffee Industry

Ana-Maria Parente-Laverde

Universidad de Medellin, Colombia

amparente@udem.edu.co

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0459-4291

Abstract. Dependency on natural resources has made economies unstable because of the fluctuation of commodity prices. However, coffee production has not had this effect on the Colombian economy owing to the process of upgrading the value chain, with the Colombian National Federation of Coffee Growers taking the lead. Using a case study methodology, the present article aims to analyse how the process of upgrading the value chain in the Colombian coffee industry has contributed to the economic development of the country, represented as an improvement of the country’s infrastructure and living conditions, economic growth, industrialisation level and education access perspectives.

Keywords: Colombia, upgrading value chain, economic development, coffee industry

Received: 7/5/2019. Accepted: 2/3/2020

Copyright © 2020 Ana-Maria Parente-Laverde. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Countries with abundant natural resources have large advantages when entering international markets and obtaining financial resources that can be used to develop local industries (Gunton, 2017; Perez, 2013). Unfortunately, countries such as Colombia and Venezuela have concentrated their economic and internationalisation activities on the export of resources such as oil, gas and agricultural products, without any added value (Parente & Goda, 2016). This has generated low levels of economic industrialisation and high levels of economic instability in these economies, due to their dependency on international commodity prices.

The coffee industry in Colombia has been one of the few sectors that has been able to upgrade their value chain, innovate and industrialise, resulting in Economic Development (ED) for the country, particularly for regions producing coffee. This paper aims to study how the process of upgrading the value chain in the Colombian coffee industry has contributed to the economic development of the country. First, the concepts of value chain and economic development are reviewed, followed by the description of the methods and materials. Finally, the upgrading process of the Colombian coffee industry is presented, followed by the explanation of its effects on the economic development of the nation.

Value chain and the upgrading value chain process

Literature on value chain is mostly multidisciplinary due to the involvement of diverse actors and its relationships (Kilelu et al., 2017). Value chain includes all the activities that are part of the process of conceiving a good or service, transforming it from raw materials into a final product and delivering it to the final consumer (Robbins & Coulter, 2015).

Recently, because of globalisation, the concept of upgrading value chains has become more relevant in the economic field. ‘Upgrading’ means moving from primary activities that have poor added value, to the production of goods or services with higher value and competitive position (Giuliani, Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2005; Ricciotti, 2019). It is important to mention that although upgrading a production process may require innovation activities, upgrading is not necessarily synonymous with ‘innovating’ (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2000). Contrary to this statement, studies on the upgrading process in the agro-industries have had an innovation focus (Kilelu et al., 2017).

This study aims to contribute to the literature by studying upgrading in the agro-industry from different approaches. There are four ways or approaches of upgrading value chains: (1) process upgrading, which refers to a method of producing goods and services in a more efficient way through the use of technology (Tian, Dietzenbacher, & Jong-A-Pin, 2019); (2) product upgrading, which means developing more sophisticated products (Moyer-lee & Prowse, 2012); (3) functional upgrading, which requires taking control of the added value functions of the value chain, like branding (Li, Frederick, & Gereffi, 2019) and (4) intersectional upgrading, which refers to using the capabilities acquired in one industry to enter a new one (Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2011).

The process of upgrading may have a positive impact on a sector or industry. Firstly, it allows a better response to competitors in a globalized market (Ricciotti, 2019) through high added value activities that can result in a better positioning process in the international market (Lee, Szapiro, & Mao, 2018). Secondly, it helps to enhance performance by improving value chain practices (Kilelu et al., 2017), which may result in higher returns on investment (Bolwig, Ponte, du Toit, Riisgaard, & Halberg, 2010); however, these asseverations require further discussion in the literature.

Development

For the present study economic development will be defined as the process of using economic wealth as a resource to improve the well-being of a community (Guigale, 2017). ED differs from the concept of economic growth, which refers to the progression of a country’s output mainly in terms of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2018). Both concepts are different even though they are related, i.e. development is connected not only with economic growth but also with improvements on education (Kruss, McGrath, Petersen, & Gastrow, 2015), technology (Kozma, 2010), infrastructure (Ansar, Flyvbjerg, Budzier, & Lunn, 2016), quality of life (Montenegro, 2017), poverty reduction and industrialisation of the economy (Guigale, 2017).

Calderón and Servén (2008) have identified links between ED and the quality of infrastructure, poverty reduction, social equality and a high educational level. However, it is not possible to say that one element is the cause or consequence of the other—only that they are interconnected, and that this generates and maintains ED for a region.

The first element to be discussed is infrastructure. It comprises roads and access to public services such as electricity, water and internet access (Ali & Pernia, 2003). For instance, the construction and improvement of roads allows an advance to urban productivity as well as rural business, thereby it generates economic growth (Deng, 2013), better salaries for farmers and possible poverty reduction (Chotia & Rao, 2017).

Another important area that is connected to ED is education. These two elements have a bidirectional relation, a higher economic growth can create a surplus, which can be invested in the education system, injecting qualified labour into the market and possibly improving productivity (Gylfason, 2001).

One more element associated to ED, industrialisation, is a component that brings growth but not necessarily development. Industrialisation, if it is well managed, can generate ED through the reduction of poverty and income inequality, as in the case of Korea (Kwon & Yi, 2009). However, when it is not managed properly, economic growth can become concentrated among a few groups or people. Mexico is an example of an industrialised country that has a high level of income inequality (Kniivilä, 2007).

Upgrading of value chains has an impact on the economic development of countries, in particular, undeveloped and developing ones, in which it can accelerate the process (WTO & OECD, 2013), allowing companies from these regions to compete globally with value-added products and to gain profits from different stages of the value chain. The economic gain of this process, in the long run, has an impact on local employment, income and living standards (The World Bank, 2013).

Material and methods

As Yin (2014) suggested, a case study should be used when answering questions of how and why. This method was used because it allows the researchers to develop a contextualised explanation of a phenomenon (Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, 2011). In this study, the context is important, because it allows the researcher to juxtapose the theory with a real case of upgrading in a developing country.

This research work is aimed at understanding how the process of upgrading the coffee value chain led by the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia (FNC for its Spanish translation) has contributed to the economic development of Colombia, particularly the coffee-producing regions.

The present article follows the structure of a case study, focusing only on one unit of analysis, the Colombian coffee industry. This industry was selected due to its exceptional application of upgrade strategies in Colombia and its historical effect on today’s Colombian economy and social context. As mentioned in the literature, underdeveloped and developing countries can take greater advantages of upgrading their value chains, therefore Colombia as a developing country was carefully chosen for this case study.

This is a retrospective study; it uses descriptions and observations of past events that have already been documented. These resources allow the analysis of concepts and elements in a particular context, as well as their effect on the variables involved (Miller, Cardinal & Glick, 1997). In this research work, the value chain upgrading process of the Colombian coffee industry was analysed from its origin in the nineteenth century until the decade immediately preceding the current one, a period that ends with outstanding events such as the creation of Juan Valdez Coffee shops (shops located around the world, owned manly by the FNC and sellers of Colombian coffee exclusively) and the launch of a specialty coffees product line.

Secondary sources of information, such as historical documents, official reports, books, videos and interviews conducted with former executives of the FNC, were used to develop the case study. Different sources of information are included to enhance the validity of the data. The sources used are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Sources of Information

|

Type of Source |

Title |

Year |

Origin |

|

Books |

Colombian Coffee: Growing for the future |

2017 |

Universidad EAFIT |

|

El café en Colombia 1850-1970: Una historia ecónomica, social, y política |

2002 |

El Colegio de Mexico |

|

|

Juan Valdez: La estrategia detrás de la marca |

2017 |

Ediciones B |

|

|

Reports and official documents |

Ferrocarriles en Colombia 1836–1930 |

2011 |

Central Bank of Colombia |

|

Coffee, Cooperation and Competition : A Comparative Study of Colombia and Vietnam |

2009 |

Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

|

|

La política cafetera 2010-2014 |

2015 |

FNC |

|

|

A beatiful story |

2019 |

FNC |

|

|

Interviews/ videos |

Interview with the FNC CEO |

2018 |

City TV |

|

Interview with Professor Juan Carlos Lopez Diez |

2018 |

Personal meeting |

|

|

Interview with Felipe Castañeda. Leader of the coffee sector in the Chamber of Commerce of Medellin |

2019 |

Personal meeting |

|

|

Type of Source |

Title |

Year |

Origin |

|

Academic publications |

The International Coffee Agreement: economics of the nonmember market |

1990 |

European Review of Agricultural Economics |

|

El acompañamiento institucional en el desarrollo del sector cafetero colombiano |

2015 |

Revista Finanzas y Politica Económica |

|

|

Regionalización de la calidad del café de Colombia Denominaciones de origen como estrategia de valor agregado |

2013 |

Manual Del Cafetero Colombiano |

Source: Own construction

To systematise the information, matrixes were constructed to consider the categories of value chain, upgrading of the value chain and, finally, the effect of this process on the different components of economic development. Subsequently, a logical sequence process was used to connect the data collected with previous literature. This paper follows a qualitative research pattern by using narration to describe the results of the research (Conle, 2000).

Results and discussion

The coffee industry in Colombia

The origin of coffee farming in Colombia is uncertain, although it is broadly accepted that the seed was brought by the Jesuits in the 1730s. It might also have entered the country through the Santander region from Guyana; later, the first coffee crops were located in the oriental part of the country (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, 2010b).

Nevertheless, the high volume of coffee production in Colombia started in the middle of the nineteenth century consequent to the colonial influence in the region; thus, a small group of people belonging to the ‘elite’ controlled production factors. By the end of the century, production had expanded to other territories of the country, such as Caldas and Antioquia, which led to an increase in the product volume. Unfortunately, in the first years of the twentieth century, coffee prices decreased, making the production of the bean less attractive. This situation was exacerbated by a conflict known as ‘La guerra de los mil días’, which forced the peasants to leave the fields to fight. Much of the croplands were destroyed as they became battlefields (Cerquera & Orjuela, 2015).

Origin of ‘Federación Nacional de Cafeteros’

The establishment of the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia dates to the 1880s, when the Colombian Farmers’ Association (SAC) was created. This group of landowners promoted agricultural development and intended to report relevant information about international markets to other members of the industry. Subsequently, the evolution of this society led to the establishment of the FNC in 1927 as a private non-profit entity that sought to support members on issues such as technical assistance, access to credit, storage facilities and the improvement of the bargaining power of coffee growers with the main global coffee buyers (Reina, Silva, Samper & Fernández, 2012).

At its inception, the FNC established a structure based on three organisational systems: (1) a technology transfer system to provide technical support and thus improve the quality of the grain; (2) an internal (national) and external (international) commercialisation system and (3) an international marketing scheme that allows the Colombian product to enter new markets and to position the product in the minds of global consumers (Reina et al., 2012). This structure shows that from the beginning, the FNC had the objective of upgrading the value chain to be more competitive and not just contribute to the sales of a commodity.

However, the upgrading process was not fully implemented until the end of the twentieth century, prior to which the coffee market was highly affected by price fluctuations, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s, which had a negative impact on the economic growth and political stability of producer countries. Therefore, in 1963, and with the support of the UN, the International Coffee Organisation was created (Roldán-Pérez, González-Pérez, Huong & Tien, 2009).

This organisation led to the conception of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA). This arrangement, signed by the main coffee-producing countries at the time, represented 90% of the global supply and involved 44 countries, including Brazil, Vietnam and Colombia. Its main objective was to control the world’s supply of coffee in order to raise and stabilise prices, thus allowing producer countries to enjoy economic security and at the same time political security in a Cold War context (Bohman & Jarvis, 1990).

The agreement crashed in 1989 due to a new commercial dynamic of free trade and a reduced state intervention; in addition, the United States no longer needed producer countries as allies for the Cold War. The end of the agreement meant that 25 million more bags of coffee were available in the market, making the price drop to its lowest levels in 1990 (Rettberg, 2010). This affected the Colombian industry, as the growers depended on the agreement to get high income from coffee; after the 1990s, the Colombian industry had to change its strategy to access foreign markets.

Coffee value chain

The coffee value chain, described by Minten, Dereje, Engida and Kuma (2019), starts when the farmers pick the coffee grains; later, another actor in the chain dries the bean and, if necessary, shreds it. The product is then sold to a wholesaler, who roasts the coffee and sells it to retailers. Finally, they package it with the retailer’s brand and distribute it to the final consumer. Kaplinsky and Fitter (2001) additionally identified the extent to which each stage adds value to the coffee value chain. For them, farmers add 21%, collectors add 10%, traders add 18%, processors add 29% and retailers add 22%.

The process of upgrading the coffee value chain can be done through the development of new products, innovation on existing offer, productivity improvement and brand positioning (Kaplinsky, 2006). The following describes the contribution of the FNC towards upgrading the coffee value chain in Colombia.

As previously mentioned, there are four types (ways) of upgrading the value chain. This paper focuses only on the three ways used by the FNC. First, in 1938, the Colombian industry became engaged in the process of upgrading, which means producing in a more efficient way. It started with the foundation of the National Coffee Research Centre, known as ‘CENICAFE’, which aims to help coffee growers use natural resources properly while producing high-quality beans, which may result in increasing efficiency and reducing the costs of production (Alvarez, 2017).

Considering the low educational level of Colombian coffee growers and the difficulties involved in imparting personalised education to each, the FNC decided to use a communication strategy to offer technical and educational assistance in the production process to increase product quality and the productivity of the sector. This tactic involved the creation of a comic book and a TV show named ‘The Adventures of Professor Yarumo’; the character, through its daily ventures, educated the growers on how to respond to pests and climate changes and how to use tools such as a hand blender.

The education programme that started in 1985 has been successful in helping the Colombian producers to have a high quality with minimal loss of production due to external factors such as pests (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, 2018).

The second and third ways of upgrading value chains can be explained jointly. Product and functional upgrading were developed by the FNC through the implementation of the brand and character, Juan Valdez, the registration of local and national geographical indications and the creation of Juan Valdez Coffee shops.

The FNC understood that it was necessary to position the Colombian product to compete in a hostile market, which is the reason for their introduction of four different product-positioning strategies:

1. Juan Valdez character: The advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach was engaged in the conception of the brand. This company developed the character “Juan Valdez” with the main objective of creating a long-term educational programme. This character, physically similar to a Colombian coffee grower, would show to the international consumer the commitment and dedication necessary to produce coffee of the highest quality. Although the campaign was initially directed toward final consumers, it was also applicable to roaster companies and distributors; i.e. those companies could use the Juan Valdez character in their campaigns in order to differentiate their products from other international competitors (Parente-Laverde, 2017).

2. The ‘ingredient brand’: This innovation was inspired by the decreased demand for regular coffee and an increase in the demand for differentiated products among consumers (particularly North Americans). This forced the brand to develop a strategy that would create an elegant and premium product. Therefore, the ingredient brand1 was launched (Figure 1) to allow distributors, roaster companies, restaurants and hotels to use it, and in that way conferring added value to the product (Reina et al., 2012).

Figure 1: Ingredient brand

Source: Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (2010a)

This strategy allowed Colombian coffee to create a demand that was 2.5 times more than the products from other countries, and 60% of the consumers were willing to pay more for the Colombian bean (Reina et al., 2012). In addition, alliances with luxury restaurants, airlines and cruise lines were developed to position Colombian coffee in the high-end market.

3. Development of specialty coffees: As a new market trend focusing on specialty coffee emerged, the FNC decided to develop new products with the Juan Valdez brand, such as pods, coffee extracts, essences and freeze-dried coffees (Reina et al., 2012).

4. Geographical indications: FNC’s legal and scientific teams undertook the process of registering Colombian coffee as a geographical indication. By the 1980s, the Federation had succeeded in ensuring that coffee experts and agricultural scientists recognised the great human, financial and logistic efforts needed to produce the Colombian product; however, at the time, coffee beans from Colombia did not have geographical indication (Quiñones-Ruiz, Penker, Vogl & Samper-Gartner, 2015).

The process began in 2004, when the National Coffee Congress, the entity with the greatest power in the FNC, gave the order to initiate the registration of a geographical indication to prevent Colombian coffee farmers from being threatened unethically by some competitors (Quiñones-Ruiz et al., 2015). This process also sought to allow consumers to have a legitimate and closer relationship with the Colombian product. The costs to fulfil this objective were assumed by the Federation, particularly by CENICAFE, which compiled all the information for the legal team. Beyond the scientific and legal costs, the greatest expenses were incurred in the process of communicating the strategy to the growers and educating them so that the denomination was seen, by them, as a differentiation tool in their commercial strategy (Quiñones-Ruiz et al., 2015).

Finally, after almost half a decade, the geographical indication of Colombian coffee was registered in regional bodies such as the European Union, the United States, the Andean Community of Nations and the Colombian government. Companies and brands such as Sara Lee, Nestle Nespresso, Colcafé, Café Quindío, Illy Café and Mondelez, are authorised users of the geographical indication in their packaging and promotional pieces (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, 2010a).

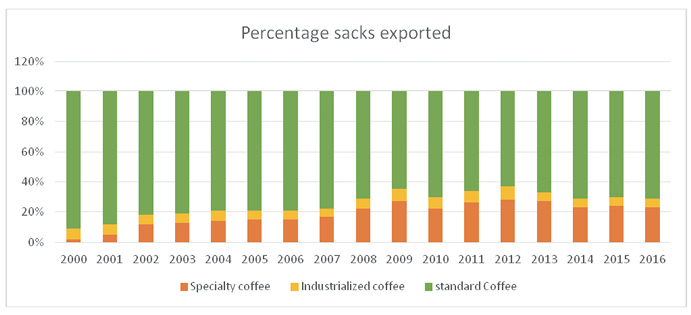

Since 2004, the Federation, along with different entities involved in the governance of the indication, has developed technical studies to analyse the feasibility of registering regional coffees, such as those coming from Nariño, Cauca, Huila, Tolima, Santander, Norte de Santander, Cesar, La Guajira and Magdalena (Hincapié, Elías, Suárez, Henao & Arboleda, 2013). Currently, Café de Nariño, Café de Huila, Café de Santamder, Café de la Sierra Nevada, Café de Tolima and Café del Cauca indications have been registered (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, 2020). These specialty coffees (including the ones with geographical indications) have allowed small growers to obtain a better price for the bean and replace part of the production of traditional coffee, depending on the commodity price, with specialty coffee (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of coffee sacks exported by type from 2000 to 2016

Source: Alvarez (2017)

The last strategy among those employed in upgrading the coffee value chain was the conception of the Juan Valdez Coffee shops. In 2002, the FNC made the decision to position the Colombian coffee brand further by using the already popular character of Juan Valdez and establishing premium coffee shops to sell their own product and accessing other sources of profit in the value chain. The shops were franchised to third parties in order to facilitate distribution and rapidly expand into new markets such as the United States, Chile, Ecuador, China and Colombia, among others (CITY TV, 2018).

Table 2 presents a summary of the value chain upgrading strategies developed by the FNC.

Table 2. Value Chain Upgrading Strategies

|

Type |

Definition |

Strategy |

Effect on ED |

|

Process |

Producing goods and services in a more efficient way, using technology and reorganisation |

Creation of CENICAFE; implementation of quality and efficient programmes and education to growers with Professor Yarumo initiative |

Improvement in infrastructure, economic growth, industrialisation and quality of life of the population |

|

Product |

Developing more sophisticated products |

Café de Colombia ingredient brand strategy; geographical indications; speciality coffees and Juan Valdez shops and character |

|

|

Functional |

Taking control of the added value functions of the value chain |

||

|

Intersectional |

Using the capabilities acquired in one industry to enter a new one (Giuliani & Bell, 2005) |

Not applied |

|

Source: Own construction

Contribution of the Colombian coffee value chain upgrade to the economic development of the country

The effect of upgrading the value chain on economic development is analysed through the elements of economic growth, industrialisation, education and infrastructure.

Economic growth and industrialisation. The coffee industry in Colombia was the first economic activity to penetrate the international market. In fact, the bean was mainly produced for international consumption. Between 1908 and 1989, coffee was the most exported product by the country. In the 1990s, Colombia opened its economy to allow other industries to supply local and international markets, which resulted in a lower participation of coffee exports in the total sales of Colombia abroad, but not affecting its export volume (Grupo de Estudios del Crecimiento Económico, 2002).

Table 3. Colombian Exports by Product

|

Year |

Coffee Exports |

Oil Exports |

Banana Exports |

Gold Exports |

Other Exports |

Total |

|

1908-1924 |

59% |

0% |

6% |

10% |

25% |

100% |

|

1925-1949 |

66% |

16% |

3% |

8% |

6% |

99% |

|

1950-1969 |

71% |

13% |

3% |

2% |

10% |

99% |

|

1970-1989 |

46% |

5% |

4% |

5% |

40% |

100% |

|

1990-1999 |

18% |

18% |

5% |

3% |

56% |

100% |

Source: Grupo de Estudios del Crecimiento Económico (2002)

The high volume of Colombian coffee exports resulted in high revenues for the country, which contributed to the country’s economic development. Coffee profits have been used to initiate other businesses, such as the sugar, cocoa and tobacco industries, which, over time, have consolidated into current multinational companies such as the candy manufacturer Colombina and the beverage producer Postobon (DINERO, 1997). This is the main contribution of the coffee sector and its upgrade to the industrialisation of the country.

Infrastructure. The coffee industry, as one of the oldest in Colombia, collaborated in the development of the country’s infrastructure, bringing economic development to the coffee-growing areas. The infrastructure expansion was driven initially by the investment of the FNC, and later it was driven by public resources and private entities (Palacios, 2009). The initial infrastructural growth generated by the coffee industry was an extension of the national railway network. In the nineteenth century, Colombia only had one railway in the territory that nowadays is part of Panama, which connected the Pacific and Atlantic oceans (Banco de la Republica de Colombia, 2017).

With the development of the coffee industry, transportation infrastructure (mainly railways) was constructed to transfer the bean to/from ports and production centres (Tirado Mejía, 2017). This infrastructure was later used by other industries, such as the mining and sugar industries, and to transport products imported to the main cities in the middle of the country (Palacios, 2009). Table 4 lists railway expansions between 1885 and 1927.

Table 4. Extension of the National Railway Network

|

Year |

Total Length (km) |

|

1885 |

236 |

|

1898 |

513 |

|

1910 |

875 |

|

1915 |

1.114 |

|

1920 |

1.138 |

|

1927 |

2.281 |

Sources: Tirado Mejía (2017)

Railway construction was not the only contribution of the coffee industry to the development of Colombia’s infrastructure. Ports and rails were developed using the revenues from the sale of coffee abroad (Pérez, 2013). According to Vélez (2017), from 1944 to 2015, 7.6 billion of COP was invested in infrastructure, with 61% of this value allocated to providing public services and improving the quality of life of the population; 25% to the construction of roads; 12% to the construction of educational and health facilities and 2% to other production facilities.

The investment from the FNC, public and private entities and the relatively high income of the population in the coffee areas has elevated the quality of life of the population in this zone, compared with other areas of the country. Table 5 presents unmet needs in terms of housing, public services, economic dependency and education access of coffee and non-coffee regions in Colombia.

Table 5: Comparison of Unmet Needs in Coffee and Non-coffee Areas in 2012

|

Component |

Coffee areas |

Non-coffee areas |

|

Physically inadequate homes |

14% |

23% |

|

Homes with critical overcrowding |

8% |

10% |

|

Homes with inadequate public services |

10% |

18% |

|

Homes with high economic dependency |

11% |

14% |

|

Homes with kids of school age that do not go to school |

2% |

2% |

|

Total unmet basic needs |

31% |

46% |

Source: Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (2014)

Conclusion

The Colombian coffee industry has been developed by taking advantage of the country’s climate and geographic conditions. Owing to the sectoral association and the creation of the FNC, the industry has boosted the country’s economy and brought financial resources for the development of other industries.

Nevertheless, the process has faced some difficulties, in recent years Colombian coffee growers have lost interest in innovating their products and commercial offer, since they perceive the FNC as a customer who will always buy their production and will be in charge of marketing it abroad. The federation has as future challenges: (1) to innovate its offer to be much more competitive internationally and surpass crises caused by low international prices, and (2) to give a more leading role to coffee growers in the upgrade process.

Colombian coffee producers and members of the value chain are confronted with a major challenge of maintaining and nourishing the Colombian coffee brand, i.e. keeping it up in the mind of consumers, but giving it a recognition for its innovation, sophistication, sustainability, variety and quality of the product. The comparative advantage given by the biodiversity of the country cannot be the only value offered by the Colombian coffee brand, that is why the future years will be determinant for the Colombian coffee industry and the economic development of the country.

The present case study shows, as a novel factor, that upgrading the value chain of industries that are highly dependent on natural resources can bring economic development in developing countries with social and economic difficulties. Economic development is expressed as cycles of infrastructure improvement, economic growth, industrialisation and improvement of living conditions. The present study can be used by other Colombian and developing countries’ industries, like the cocoa sector, as an inspiration to initiate or continue a process of value chain upgrading.

Furthermore, Colombian policy makers should use the coffee case to promote policies that give incentive to industries dependent on natural resources to use upgrade strategies, especially in distant and poorly industrialised regions.

The case study contributes to the literature of value chain by demonstrating – from the perspective of a developing country – how the process of upgrading an industry value chain can help to develop a country economically, validating previous finds in the field.

Further research should develop comparative studies that help to analyse other industries in emerging markets and compare them to the present case, in order to find patterns of performance that can be replicated.

References

Ali, I., & Pernia, E. M. (2003). Infrastructure and Poverty Reduction — What is the Connection ? ERD Policy Brief Series, 13. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28071/pb013.pdf

Alvarez, J. R. (2017). The reinvention of the coffee industry in times of the free market (1989-2015). In Colombian Coffee: Growing for the future (pp. 196). Medellin: Universidad EAFIT.

Ansar, A., Flyvbjerg, B., Budzier, A., & Lunn, D. (2016). Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(3), 360–390.

Banco de la Republica de Colombia. (2017). Ferrocarriles en Colombia 1836-1930. Retrieved August 20, 2006, from http://www.banrepcultural.org/biblioteca-virtual/credencial-historia/numero-257/ferrocarriles-en-colombia-1836-1930

Bohman, M., & Jarvis, L. (1990). The International Coffee Agreement: economics of the nonmember market. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 17(1), 99–118.

Bolwig, S., Ponte, S., du Toit, A., Riisgaard, L., & Halberg, N. (2010). Integrating poverty and environmental concerns into value-chain analysis: A conceptual framework. Development Policy Review, 28(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00480.x

Calderón, C., & Servén, L. (2008). Infrastructure and Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Research Working Paper (4712), (September), 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejp022

Cerquera, O., & Orjuela, C. (2015). El acompañamiento institucional en el desarrollo del sector cafetero colombiano. Revista Finanzas y Politica Economica, 7(1), 169–191.

Chotia, V., & Rao, N. (2017). Impacts of Transport Infrastructure on Productivity and Economic Growth: Recent Advances and Research Challenges. International Journal of Social Economics, 44(12), 1906–1918.

CITY TV. (2018). Entrevista al gerente general de la Federación Nacional de Cafeteros | Mejor Hablemos. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KU-xFjuibhU

Conle, C. (2000). Thesis as Narrative or ‘What Is the Inquiry in Narrative Inquiry?’ Curriculum Inquiry, 30(2), 189–214.

Deng, T. (2013). Impacts of Transport Infrastructure on Productivity and Economic Growth: Recent Advances and Research Challenges. Transport Reviews, 33(6), 686–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2013.851745

DINERO. (1997). La conquista del azúcar. Revista DINERO. Retrieved from https://www.dinero.com/archivo/articulo/la-conquista-del-azucar/17161

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2018). Economic growth.

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros. (2010). Federación Nacional de Cafeteros. Retrieved March 1, 2017, from http://www.cafedecolombia.com/particulares/es/indicaciones_geograficas/Denominacion_de_Origen/usuarios_autorizados_de_la_indicacion_geografica_protegida_cafe_de_colombia/

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. (2010a). Marca Ingrediente. Retrieved April 1, 2017, from http://www.cafedecolombia.com/particulares/es/indicaciones_geograficas/Marca_Ingrediente/

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. (2010b). Una bonita historia. Retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.cafedecolombia.com/particulares/es/el_cafe_de_colombia/una_bonita_historia/

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. (2014). La política cafetera 2010-2014. Ensayos Sobre La Economia Cafetera.

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. (2018). PROFESOR YARUMO.

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. (2020). Denominación de Origen Café. Retrieved from http://www.cafedecolombia.com/particulares/es/indicaciones_geograficas/Denominacion_de_Origen/245_denominacion_de_origen_cafe_de_cauca-1/

Giuliani, E., & Bell, M. (2005). The micro-determinants of meso-level learning and innovation: evidence from a Chilean wine cluster. Research Policy, 34(1), 47–68.

Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.002

Grupo de Estudios del Crecimiento Económico. (2002). El crecimiento económico colombiano en el siglo XX (Grupo de Estudios del Crecimiento Económico, Ed.). Bogota: Banco de la Republica de Colombia.

Guigale, M. (2017). Economic Development: What Everyone Needs to Know (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gunton, T. (2017). Natural resources development. In D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, & R. A. Marston (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Geography. (pp. 1–29). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0554

Gylfason, T. (2001). Natural resources, education, and economic development. European Economic Review, 45(4–6), 847–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00127-1

Hincapié, A. M. V., Elías, H., Suárez, P., Henao, C. P., & Arboleda, C. T. (2013). Regionalización de la calidad del café de Colombia Denominaciones de origen como estrategia de valor agregado. Manual Del Cafetero Colombiano, (DECEMBER), 182–208.

Kaplinsky, R. (2006). How can agricultural commodity producers appropriate a greater share of value chain incomes? In A. Sarris & D. Hallam (Eds.), Agricultural Commodity Markets and Trade: New Approaches to Analyzing Market Structure and Instability. Edward Elgar Pub.

Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2000). A Handbook for Value Chain research. Institute for Development Studies: Brighton, UK, (September), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137373755.0007

Kilelu, C., Klerkx, L., Omore, A., Baltenweck, I., Leeuwis, C., & Githinji, J. (2017). Value Chain Upgrading and the Inclusion of Smallholders in Markets: Reflections on Contributions of Multi-Stakeholder Processes in Dairy Development in Tanzania. European Journal of Development Research, 29(5), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0074-z

Kniivilä, M. (2007). Industrial Development and Economic Growth: Implications for Poverty Reduction and Income Inequality. Industrial Development for the 21st Century: Sustainable Development Perspectives, (1), 295–332. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/publications/industrial_development/3_1.pdf Accessed: 8/08/2016, 23:07

Kozma, R. (2010). Relating Technology, Education Reform and Economic Development. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (pp. 81–87). Elsevier Science.

Kruss, G., McGrath, S., Petersen, I., & Gastrow, M. (2015). Higher education and economic development: The importance of building technological capabilities. International Journal of Educational Development, 43, 22–31.

Kwon, H., & Yi, I. (2009). Economic Development and Poverty Reduction in Korea: Governing Multifunctional Institutions. Development and Change, 40(4), 769–792.

Lee, K., Szapiro, M., & Mao, Z. (2018). From Global Value Chains (GVC) to innovation systems for local value chains and knowledge creation. European Journal of Development Research, 30(3), 424–441. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0111-6

Li, F., Frederick, S., & Gereffi, G. (2019). E-Commerce and Industrial Upgrading in the Chinese Apparel Value Chain E-Commerce and Industrial Upgrading in the Chinese. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 49(1), 24–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1481220

Miller, C. C., Cardinal, L. B., & Glick, W. H. (1997). Retrospective Reports in Organizational Research : A Reexamination of Recent Evidence. Academy of Management, 40(1), 189–204.

Minten, B., Dereje, M., Engida, E., & Kuma, T. (2019). Coffee value chains on the move: Evidence in Ethiopia. Food Policy, 83(March 2016), 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.07.012

Montenegro, Y. A. (2017). Colombia and the International Business Environment. Latin American Business Review, 18(3–4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10978526.2017.1400390

Moyer-lee, J., & Prowse, M. (2012). How traceability is restructuring Malawi’s tobacco industry (No. 2012.05). Antwerp.

Palacios, M. (2009). El café en Colombia 1850-1970. Una historia económica, social y política, (Cuarta). Mexico DF: El Colegio de Mexico.

Parente-Laverde, A. M. (2017). Reseña de M. Reina, G. Silva, L. Samper y M. Fernández, Juan Valdez: la estrategia detrás de la marca. Innovar, 27(66), 185–187.

Parente, A. M., & Goda, T. (2016). Colombia’s Exports Performance In Non-Fuel Sectors. Desarrollo Gerencial, 8(1), 71–91.

Perez, J. (2013). Economia Cafetera y desarrollo economico en Colombia. Bogota: Universitdad Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2011). Global Value Chains Meet Innovation Systems: Are There Learning Opportunities for Developing Countries? World Development, 39(7), 1261–1269.

Quñones-Ruiz, X. F., Penker, M., Vogl, C. R., & Samper-Gartner, L. F. (2015). Can origin labels re-shape relationships along international supply chains?. The case of Café de Colombia. International Journal of the Commons, 9(1), 416–439. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.529

Reina, M., Silva, G., Samper, L. F., & Fernandez, M. del P. (2012). Juan Valdez: La estrtegia detras de la marca. Bogota: Ediciones B.

Rettberg, A. (2010). Global Markets, Local Conflict: Violence in the Colombian Coffee Region after the Breakdown of the International Coffee Agreement. Latin American Perspectives, 37(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X09356961

Ricciotti, F. (2019). From value chain to value network: a systematic literature review. Management Review Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00164-7

Robbins, S., & Coulter, M. (2015). Management (14th ed.). Edinburgh: Pearson.

Roldán-pérez, A., Gonzalez-Perez, M.-A., Huong, P. T., & Tien, D. N. (2009). Coffee, Cooperation and Competition : A Comparative Study of Colombia and Vietnam. Universidad EAFIT, Colombia, Foreign Trade University (FTU), Vietnam and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 1–92. Retrieved from http://vi.unctad.org/digital-library/?task=dl_doc&doc_name=coffee-cooperation-and

The world bank. (2013). Global Value Chains, Economic Upgrading, and Gender. Washington D.C.

Tian, K., Dietzenbacher, E., & Jong-A-Pin, R. (2019). Measuring industrial upgrading: applying factor analysis in a global value chain framework. Economic Systems Research, (May), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09535314.2019.1610728

Tirado Mejia, A. (2017). Half a Century of Century of Coffee Production: From the Beginning to the Federation. In Colombian Coffee: Growing for the future (pp. 31-61). Medellin, Colombia: Universidad EAFIT.

Velez Vallejo, R. (2017). The National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia in its 90th anniversary. Achievements and challenges. In Colombian Coffee: Growing for the future (pp. 21-31). Medellin: Universidad EAFIT.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 740–762. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.55

WTO, & OECD. (2013). Value chains and the development path. In Aid for Trade At a Glance 2013: Connecting To Value Chains . WTO, OCDE.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage Publications.

1 This is a strategy in which the product has two brands, one from the manufacturer and the other from the raw material or commodity, which, in this case, is Colombian coffee.