Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2019, vol. 10, no. 2(20), pp. 257–277 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2019.10.13

The Role of Trust in Mexican Companies in Relation to the Human Factor

María Teresa de la Garza Carranza (Corresponding author)

Tecnológico Nacional de México en Celaya, México

Teresa.garza@itcelaya.edu.mx

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4877-3403

Jorge Armando López-Lemus

Universidad de Guanajuato

Campus Irapuato-Salamanca (sede Yuriria), México

jorge.lemux@hotmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6989-1065

Eugenio Guzmán Soria

Tecnológico Nacional de México en Celaya, México

Eugenio.guzman@itcelaya.edu.mx

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4713-7154

Delfino Vargas Chanes

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Programa Universitario de Estudios del Desarrollo, México

dvchanes@unam.mx

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6046-3643

Abstract. The purpose of this study is to analyze the role of trust in Mexican companies in relation to organizational factors, the leadership and career satisfaction of employees. To achieve this objective, a quantitative method of structural model equations was used. The sample consisted of 181 individuals working in service businesses, manufacturing and public service mainly. The study was done in the central part of Mexico. The study results show a positive correlation of trust of employees towards their managers related with benevolence and integrity. With regard to the relation with organizational factors, a strong relationship was found between trust and leadership but not with the policies related to management of employees. Finally, a weak relationship between leadership and career satisfaction of employees was confirmed. Through the model analyzed, it can be stated that the culture plays an important role for the development of trust in organizations. Also, recommendations for policy makers, such as ways of increasing feedback through employees, are presented.

Keywords: trust, human resources, organizational leadership, Mexico.

Received: 6/24/2019. Accepted: 12/9/2019

Copyright © 2019 María Teresa de la Garza Carranza, Jorge Armando López-Lemus, Eugenio Guzmán Soria, Delfino Vargas Chanes. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

In Mexico, the concept of trust in organizations has not been explored. Although there has been much talk about corruption in Latin American countries in recent times, the damage it can cause to the productivity of organizations must be quantified to understand its dimensions (Sanchez & Lehnert, 2018). In contrast, trust is an element that must be studied in emerging countries to identify the scope that it can have not only in the economic benefits of organizations, but also in the relations between workers (De Clerq & Bouckenooghe, 2019). In this study, we will investigate the confidence that workers have toward their managers in their organization with aspects of organizational culture and career satisfaction as professionals.

Within the Latin American context, there is a cultural diversity which is the result of the fusion of different native racial origins created by Spanish colonization. This has resulted in the emergence of new models of power over the centuries (Quijano, 1999). These models of power are reflected in formal political and economic systems that are the result of the transformation of organizations generated in colonialism (Quijano, 1995). At the same time, this fusion of thoughts and cultures has permeated the current society resulting in organizations with unique and different features that have generated the development of society, but retaining some values that have been preserved over time. This has created an unequal distribution of wealth over time where new structures for the development of organizations must emerge (Bustillo, Artecona & Perrotti, 2018).

According to Luhmann (2000), trust is functionally a mechanism for the reduction of social complexity. For this researcher, trust is a key concept to understand the American socio-economic system of the nineteenth and twentieth century as systems become more complex along with the loss of confidence. The relationship of trust between an individual and the systems must be reestablished to achieve productivity improvements. However, the connection of trust between citizens and the government may be totally lost, as is the case in some Latin American countries. This becomes evident when we analyze the performance of some politicians including, of course, the Mexican case.

Modernity has generated the current institutions and organizations of our society such as government, banks, etc. The confidence of citizens and employers is an important element to understand the economic development of Latin American countries (Zevallos-Vallejos, 2003). Authors such as Putnam (1993) have proposed that social reciprocity generates wealth compared to a society that does not trust in its institutions; trust is a social lubricant that facilitates the relationship between organizations and people. Regarding this, Bjørnskov (2012) states that, although the literature on social capital has presented a number of possibilities on the influence of social confidence in economic development, the conclusions of his work suggest that confidence has identifiable effects through two channels only: schooling and governance. This research project is intended to understand the relationship of trust, organizational culture and the career satisfaction of employees.

1. Theoretical framework

1.1 The study of trust in organizations

People, when working in an organization, develop interdependence to achieve common goals; this implies the concept of trust. Trust is present in any interaction within the organization; it is a basic element for the organization to achieve goals. For example, Newman et al. (2019) established the relationship that trust has on work performance taking into account the disposition of trade unions, the work environment and safety at work. The concept of trust is implicitly found in contracts or negotiations between both sides, but generally people either “trust” or “ not trust”. According to Arrow (1972), any business relationship has an element of trust, and in the future, trust in institutions and organizations will affect the number of transactions that are made. In other words, trust is present in any transaction that is made whether it is the purchase of a house, the negotiation between coworkers, etc. A lack of confidence can lead to legal problems for the repair of the damage or to misunderstandings with the people with whom we interact in the organization. Ashnai, Henneberg, Naudé and Francescucci (2016) linked in their study the trust in commercial relationships and their impact on economic performance.

Misztal (2013, p.3) argued that “the recent increase in the visibility of the issue of trust can be attributed to the emergence of a generalized awareness that the existing bases for social cooperation, solidarity and consensus have been eroded and that there is a need to look for new alternatives. For example, current organizations assign their employees multiple roles, which transcend functional limits since they are empowered to act in this way”. These functions are demanding and could not be performed without the confidence that those involved are competent, benevolent and able to understand the situation. The development of a model of trust in the organization is enduring and practical since you can have lasting relationships of work among employees. In the study of trust in the organizational context, Yu, Mai, Tsai and Dai (2019) found a positive interaction between employee organization relation and organizational trust. When using self-directed teams, trust takes an important role because direct observation is not useful (Flavian, Guinalíu & Jordan, 2019). Bulinska-Stangrecka and Bagienska, (2019) also demonstrated the importance of trust for team collaboration and innovation. So far, the understanding of trust can facilitate cohesion and collaboration among people (Meyer, Davis & Schoorman, 1995).

Confidence, according to Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995, p. 712), is “when the will of one of the parties is vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform in a particular order of importance for him, regardless of the ability to supervise or control that other part”. According to Sheppard & Sherman (1998, p. 422), “trust is accepting the risks associated with the type and depth of the interdependence inherent in a given relationship”. Researchers such as Burke, Sims, Lazzara and Salas (2007) and Tzafrir and Dollan (2004) have made an extensive list of the meaning of trust, some examples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Definitions of Trust

|

Definition |

Author |

|

The willingness of one person to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other party will perform an action that is particularly important to the first, regardless of the ability to supervise or control the other party. |

Meyer, Davis and Schoorman (1995) |

|

A psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based on positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another. |

Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt and Camerer, 1998 |

|

Cognitive trust refers to beliefs about the trustworthiness of another. Affective trust refers to the importance of the role of emotions in the process of trust. The confidence of the teams' behavior is based on the sensitive information that is transmitted in the members. |

Gillespie and Mann, 2004 |

|

Mutual trust is the confidence that results when one party observes the actions of another and reconsiders one's attitudes and subsequent behavior based on those observations. |

Serva et al. (2005) |

Source: Tzafrir and Dolan (2004) and Burke, Sims, Lazzara and Salas (2007)

An exhaustive analysis of the definitions of the concept of trust was proposed by Tzafrir and Dolan (2004) who concluded that there are five dimensions to identify this behavior: 1) Confidence behavior. Trust consists of systematic and consistent procedures and behaviors that are reinforced with the commitments made; 2) Demonstration of skill. Having the competence, power and knowledge to face situations where trust between people can be tested; 3) Sharing the information. It refers to being open and receptive to freely give and receive information; this creates the process of information flow to increase productivity; 4) Demonstration of concern. It implies that the parties trust that no advantage will be taken over others in such a way that the welfare of the participants will be considered; 5) Demonstration of harmony. It relates to feelings, interests, opinions, purpose and values between work relationships in such a way that harmony is created.

According to Powell (1995), trust as an absolute measure has little meaning. When deciding whether to trust someone, individuals rarely make a value judgment without gathering information about their reputation, their history, the values of the person, etc. The value of the assets that are placed in a relationship of trust will affect the judgment of the person in such relationship. Therefore, trust is not a calculation or a belonging, but it is learned and reinforced on the interaction or the transactions.

Lewis and Weigert (1985) used a sociological point of view where trust is seen as a characteristic of the social structure that facilitates the interrelations between the parties. This approach can be useful in understanding a generalized level of trust between individuals that can improve their ability to interact. However, if an approach of this type is used, it is not possible to identify the specific actions that can lead to having more confidence by a team or person, which tells us that its current usefulness is limited. Regarding the social capital of the organization, Creed and Miles (1996) have described trust as a “social glue” or a “social lubricant” that allows high diversity, global organizational structures, absence of which will lead to a lack of trust between the parts of the social fabric and cause failure.

Authors such as Atkinson and Butcher (2003) argue that there are theoretical difficulties in constructing an integrated vision of the term trust. Given the nature of trust, which is difficult to observe and measure, it is closely related to social rules and customs. Therefore, it is a socially constructed phenomenon. In other words, trust will represent different positions according to the customs and social context. Also, another issue that must be considered in establishing a trust relationship is the time pressure. Gazdag, Haude, Hoegl and Muethel (2018) conducted experiments in relation to time and trust, and found that managers have to develop strategies for building a trust relationship independently of time length.

Mayer and Davis (1999) argue that trust is made up of three factors: ability, benevolence and integrity. Ability is a group of skills, competencies and characteristics that allow influencing some of the group members. Benevolence is the degree of interest that an administrator or organization has towards their employees. For example, if an employee believes that a manager cares about the interests of the employees, the manager will be seen benevolent towards the employee. Integrity is defined as the perception of the employee towards the organization that adheres to a set of principles that the trustor finds acceptable.

Mayer and Davis (1999) proposed that, over time, the employee will evaluate the results in a positive way, in comparison with the previous ones, according to their “vulnerability”. According to these authors, vulnerability is the ability to give confidence or withdraw it according to the situation. For example, if the employee’s vulnerability leads to results that the employee believes are favorable, the employee will positively reevaluate some combination of the three factors (ability, benevolence and integrity). Based on the model, there are at least two ways that trust can develop. In addition to evaluating previous results of employee vulnerability and reassessing honesty, the model suggests that other factors may change the perception of reliability. Honesty is affected by three different factors (capacity, benevolence, and integrity), we must reassess the perception of the employee that will impact on trust. For example, if an employee’s actions reflect the movement of the learning curve, the perception of the employee’s skill will rise. This movement of the learning curve is not necessarily linked to the vulnerability of the employee; therefore, vulnerability is not related to honesty.

The importance of trust as a focus of the organization’s recent research in the social sciences is because it reflects the accumulation of substantial evidence and varied benefits, both individual and collective, that accumulate when trust is given, either in the organization or in society (Kramer, 1999). Perhaps the main finding in this regard has been explained by Putnam (1993), who defined trust as a critical factor in understanding the origins of civic engagement and elucidated its role in the development of democratic regimes in Italian communities.

Mexican organizations like any other of the world also manage a relationship of trust between subordinates and managers. However, some authors such as Hofstede (2011) have described Mexican society as highly collectivist and with a great distance in power between heads and subordinates. This characteristic implies an unequal distribution of resources, it is necessary to study the level of trust and the factors that influence this phenomenon. As mentioned above, a relationship of trust helps to improve productivity in organizations because it avoids the establishment of controls in any work or task that is assigned to employees. Leach-López, Leach and Lee (2019) found that Mexican workers are changing their values, becoming less collectivist, and the power distance is diminishing. As mentioned above, a relationship of trust helps to improve productivity in organizations because it avoids the establishment of controls in any work or task that is assigned to employees. This study will allow Mexican managers to create a better understanding of the relations with employees in the work place.

1.2 The human factor in organizations

Nowadays, the trend of globalization of organizations is important to understand the true value that people have. The human factor should not be considered as a strategic resource only, but the most important resource of any organization (Radhakrishna & Raju, 2015). People provide the real value of organizations through their skills and abilities. Organizational talent is an asset that arises from the organization, and it is necessary to cultivate it through relationships so that it can achieve better productivity and competitiveness indexes.

There are many factors that affect workers in the organization, especially when it comes to organizations where relations between people are complicated due to cultural factors, communication, hierarchy, etc. In a research developed by Valizade, Ogbonnaya, Tregaskis and Forde (2016), where the objective was to look for the “win-win” relationship on the part of employers and workers, the authors suggested that association practices should be analyzed and reinforced with an adequate climate. These partnership practices should not be vulnerable to economic changes and should remain stable over time to achieve job satisfaction among employees. Mayseless and Popper (2019) highlighted trust as a key variable to understand the human relations at work. In this sense, Human Resources practices and their performance have been studied by several authors (Huselid, 1995; Alfes, Shantz, Truss, & Soane, 2013).

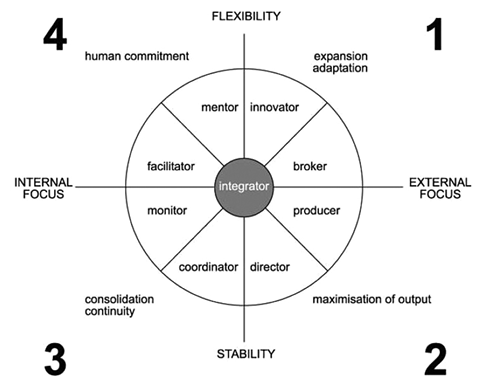

A model widely used to measure organizational culture and relationships at work is the model developed by Cameron and Quinn (2005). The model basically has two key dimensions: a) The dimension of flexibility and stability and b) The dimension of internal or external focus. These dimensions are opposed depending on the type of culture that occurs in an organization. In other words, an organization can show flexibility in guiding its products or services, but then it would no longer have organizational stability. In the same way, it can be internally oriented as it can be a bureaucratic organization, or it can be oriented to the clients.

The dimensions covered by the Cameron and Quinn (2005) model are: organizational leadership, employee management, organizational cohesion, strategic emphasis and success criteria. In this study, only two variables will be taken to identify the organizational practices related to human resources. The management’s inclusion of human resources within the organizational culture model is crucial for the evaluation of culture and implies the roles that a leader must present with his staff. The behaviors presented by the leaders are complex and contradictory (Denison, Hooijberg & Quinn, 1995), these behaviors can be represented through Figure 1.

Figure 1. Behavior of the Leaders

Source: Vilkinas and Cartan (2001)

The figure shows the roles a leader can take depending on the activities he has to perform. These activities are situational as proposed by Hersey and Blanchard (1993) in their model. Leaders must show a wide range of behaviors to be effective and must be able to integrate both internal and external approaches into their actions, but also stability and flexibility (Denison, Hooijberg & Quinn, 1995). These leadership actions directly influence the management of employees reflecting the type of behavior typical of the leadership style (Cameron & Quinn, 1999).

The model of Quinn et al. (2014) shown in Figure 1 illustrates the complexity of behaviors that a leader has. The complexity of a leader’s behavior is the ability to develop multiple roles and behaviors that circumscribe the variety of tasks involved in the organizational context (Denison, Hooijberg & Quinn, 1995). To illustrate the paradoxical concept of the model, we will mention that there are situations within the organization where monitoring and control is required, but there may be other situations that require a leader who innovates and adapts at the same time.

Leaders are constantly in contact with complex and challenging environments. It can be argued that there are multiple definitions and theories that address the issue, some theories emphasize the personal characteristics of the leader, other accentuate their functions within an organization and some more focus on the particular circumstances of the individual considered a leader, some other theories point to the circumstances of its environment. According to Northouse (2013), the approaches most used to address leadership are: the style of the traits (Stogdill, 1974), the style approach (Blake & Mouton, 1985), the situational approach (Hersey & Blanchard, 1993), the theory of contingency (Fiedler & García, 1987), the theory of member-leader exchange (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) and transformational leadership (Bass, 1997). These approaches or theories have been studied extensively by various authors since the mid-twentieth century to date and have been applied in various types of organizations such as military, education, business and government. The main goal in conducting these studies is to increase the leadership of managers in order to achieve organizational objectives. In a study conducted by Carter, DeChurch, Braun and Contractor (2015), a review of leadership theories highlights four main factors:

1) Leadership is relational. At a minimum, the leadership involves two people. Without followers, there is no leadership.

2) Leadership is placed in context. The contingent theories suggest that the leader considers the specific situation of the context. The leaders act by considering the personnel they are in charge of and the interaction of their environment.

3) Leadership is a pattern. The leadership relationship between different people is unique and constitutes a pattern of action.

4) Leadership can be formal and informal. Leaders can originate from a position of power in the organization or they can arise naturally among the members of a group.

The study supports the theory of complexity of leadership proposed by Denison, Hooijberg and Quinn (1995). In their study, they found that highly effective leaders are closer to the proposed model than ineffective leaders. The effective leaders showed the use of the eight proposed roles (facilitator, mentor, innovator, intermediary, producer, director, coordinator and monitor). According to Lavine (2014), the practice of leadership becomes more effective when one is aware of the paradoxes of the concept and the tension that exists between the skills to be developed; while a leader has more knowledge, he will improve his performance based on the model proposed in Figure 1.

Another factor that should be studied to understand the human factor in organizations, which is generally a predictor of other variables such as performance, is satisfaction with career or professional performance (Janssen & Van Yperen, 2004). Satisfaction can be evaluated from an internal or external perspective; in the internal case, it helps to give meaning to the experiences that are achieved and is determined by the individual. It is also a quick evaluation where self-imposed standards are compared. In the case of external evaluation, different actors are required to be involved in the process, and it could be considered a peer and supervisory evaluation (Abele, Hagmaier & Spunk, 2015).

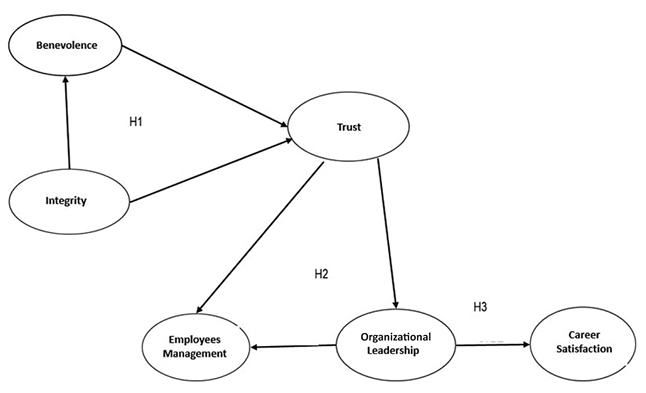

Figure 2. Hypothetical Model According to the Theoretical Framework

Source: Own elaboration

According to Janssen and Van Yperen (2004), supervisors or bosses are the outstanding agents to determine the products of their subordinates’ work; this productivity is also determined by the quality of the relationship that is maintained between the leader and the subordinate. Then the motivation to the achievement of the subordinate will be determined by the need to advance in the professional careers of the employees. The need to have standards and meet or exceed them helps a person self-evaluate positively, but there may also be situational variables to set these standards (Harris, Anseel & Lievens, 2008). Taking into consideration what is stated in this theoretical framework, the following hypotheses can be constructed according to Figure 2:

H1. There is a relationship between integrity, benevolence and trust perceived by workers in relation to their employers.

H2. There is a relationship between trust, leadership and employee management perceived by workers in relation to their employers.

H3. There is a relationship between leadership and career satisfaction perceived by workers.

2. Methodology

A descriptive and correlational study was carried out through structural equations to find the relationships between trust and its repercussions in the human factor of organizations. In order to perform a structural model, the reliability and validity tests of the scales were first carried out by means of the exploratory factor analysis technique using the SPSS software. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a statistical method that helps to understand models where several variables intervene in a model that goes beyond multiple linear regressions. According to Fox (2002), the models of simultaneous equations are multivariate multiple regressions. SEM is a variant of multivariate models which has been used to explain complex processes in which there is interest in using independent variables, intervening variables and dependent variables. This model is more advanced than multivariate statistics models because it allows us to find relational paths between the different types of variables. The idea of structural equation models is to represent causal relationships between two or more variables simultaneously. The analysis of structural equations was carried out using the AMOS V 22 software.

2.1 Description of the sample

The sample was random from diverse industries in the State of Guanajuato, this is a condition for it to be representative and therefore useful. Additionally, it should reflect the similarities and differences found in the population, that is, exemplify the characteristics. The sample of the present study integrated 181 individuals who are workers employed by diverse industries of the Laja-Bajío region in the State of Guanajuato. We used the database of the External Service Department of our universities (Tecnológico de Celaya and Universidad de Guanajuato) to gather the data. The individuals were contacted by email. The region is characterized as having automotive industry, footwear and food production, etc.

Regarding the studied population, it is worth mentioning that 53% belong to the masculine gender and 47% feminine, the age oscillates between the 21 and 59 years, with the following distribution: 37% of those 21 to 30 years old, 41% belonging to the age group between 31 to 40 years old, and 22% of more than 40 years old. In relation to the academic level of the participants, they are graduates from the universities, and most of them have a bachelor’s degree (72%) or higher (28%). Their work experience varies from one to ten years (55%), from ten years to 20 years (37%) and more than 20 years (8%). The workers are engaged in the following kinds of business: manufacturing 40%, services 36%, public management 20% and others (agriculture, mining, construction, etc.) 4%. In terms of the size of the organizations studied, 23% are with less than 100 employees, 36 % employ between 101 and 1000 employees and 41% have more than 1000 employees.

2.2 Scales used

The instruments related to trust, integrity and benevolence were taken from the scales developed by Mayer and Davis (1999), using a Likert scale from 1 to 9 where 1 implied “strongly disagree” and 9 “highly agree”. Leadership and management of employees were measured considering the organizational culture scale developed by Cameron and Quinn (2005). Just like in the previous case, a Likert scale from 1 to 9 was used, with 1 implying “strongly disagree” and 9 “highly agree”. To measure the satisfaction of the career, the same scale with 9 items was taken from Greenhaus, Parasuraman and Wormley (1990). The translation of the instruments into Spanish was carried out by two experts on the subject, and to ensure the accuracy of the words, it was translated into English again. This procedure is known as “back translation” for multicultural studies (Brislin, 1970). First, we obtained the descriptive data and the Pearson correlation of the variables under study, this is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Pearson’s Correlations of Variables

|

Variable |

Media |

DS |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1 Integrity |

5.73 |

2.03 |

|||||

|

2 Benevolence |

5.32 |

1.98 |

0.806** |

||||

|

3 Trust |

5.64 |

1.94 |

0.846** |

0.785** |

|||

|

4 Leadership |

5.40 |

2.15 |

0.641** |

0.595** |

0.577** |

||

|

5 Employees Management |

5.60 |

2.08 |

0.501** |

0.485** |

0.431** |

0.773** |

|

|

6 Satisfaction |

7.38 |

1.52 |

0.097 |

0.039 |

0.039 |

0.099 |

0.075 |

Source: From data analysis and the results of SPSS software. ** p<0.01

As a second step to evaluate the validity of the questionnaire, an exploratory factor analysis was used through the SPSS software. This analysis allows us to identify the factors associated with the questionnaire. In order to obtain a tested questionnaire, two associated types of tests are required with this analysis: The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin indicator (KMO) and the Bartlett’s sphericity test, and the variance explained by the questionnaire. The KMO test contrasts the partial correlations between variables, it can be calculated for individual or multiple variables and relates the square of the correlation between the variables with the square of the partial relation between the variables in such a way that it is a measure of the adequacy of the sample. The closer the value to 1 is obtained, the better the KMO test. This implies that the correlation patterns are relatively compact; values greater than 0.60 are considered acceptable. Bartlett’s sphericity test evaluates the applicability of the factorial analysis of the variables studied, so that finding an index lower than 0.05 rejects the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix to determine if the correlations are significant among the variables and, finally, the explained variance tells us how much the questionnaire explains the phenomenon studied.

The exploratory factor analysis of the benevolence scale related to senior management is shown in Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.874. The variance explained was 67%.

Table 3. Factorial Loads of Benevolence Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

Top management really watches over what is important to me. |

0.909 |

|

Top management is concerned about my well-being. |

0.862 |

|

My needs and wishes are very important for top management. |

0.814 |

|

The top management would go out of their plans to help me. |

0.805 |

|

Top management would not consciously do something to harm me. |

0.687 |

Source: Items adapted form Mayer and Davis (1999)

To assess the integrity of top management, six items were used. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.90, the variance explained was 68%. The results of the factorial loads are presented below in Table 4.

The factorial loads of the confidence items are shown below in Table 5. Cronbach’s alpha for this set of items was 0.802, and the variance explained was 62.8%.

Four items were used to evaluate the concept of leadership, as in the previous cases, the scale used was a Likert of nine points. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87, the explained variance was 72%, and the factorial loads of the items are shown below in Table 6.

Table 4. Load Factors of Integrity Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

The behavior of senior management is guided by solid principles. |

0.893 |

|

Top management has a strong sense of justice. |

0.872 |

|

Top management strives to be fair in dealing with others. |

0.870 |

|

The actions and behaviors of senior management are congruent. |

0.802 |

|

I identify with the values of senior management. |

0.789 |

|

I never have to ask myself if the address can meet his word. |

0.709 |

Source: Items adapted form Mayer and Davis (1999)

Table 5. Load Factors of Trust Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

Top management is aware of the work that needs to be done. |

0.724 |

|

I am willing to let top management make decisions that influence issues that are important to me. |

0.785 |

|

I would be willing for top management to decide on my future in the company. |

0.828 |

|

I would trust to give senior management a task or problem that was critical to me, even if I could not monitor their actions. |

0.829 |

Source: Items adapted form Mayer and Davis (1999)

Table 6. Load Factors of Leadership Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

Leadership in the organization usually tries to be an example of coordination, organization, and efficiency with softness. |

0.902 |

|

Leadership in the organization usually tries to be an example of good sense, aggressiveness, and orientation to results. |

0.885 |

|

Leadership in the organization usually tries to be an entrepreneurial, innovative, and risk-taking example. |

0.820 |

|

Leadership in the organization usually tries to give an example of paternalism, acts as a mentor and facilitates things. |

0.771 |

Source: Items adapted from Cameron and Quinn (2005).

The management of employees was evaluated considering four items according to Cameron and Quinn (2005). The Cronbach alpha 0.853 result of the analysis was 69%, and the variance explained was as shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Load Factors of the Employee Management Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

The management style in the organization is characterized by individual initiative, innovation, freedom, and uniqueness. |

0.891 |

|

The management style in the organization is characterized by job security, compliance, predictability, and stability in relationships. |

0.857 |

|

The management style in the organization is characterized by teamwork, consensus, and participation. |

0.805 |

|

The management style in the organization is characterized by a hard competitiveness, high demands, and achievements. |

0.778 |

Source: Items adapted from Cameron and Quinn (2005)

In the case of the items related to career satisfaction, the factorial loads are shown in Table 8 below. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained was 0.926, and the variance explained was 77%.

Table 8. Factor Loadings of Career Satisfaction Items

|

Item |

Load Factor |

|

I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting the goals of my career. |

0.927 |

|

I am satisfied with the progress of the goals that I trace in my career. |

0.904 |

|

I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting my income goals. |

0.899 |

|

I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career. |

0.853 |

|

I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting my goals to develop new skills. |

0.818 |

Source: Items adapted from Greenhaus, Parasuraman and Wormley (1990)

Next, Table 9 presents a summary of the main indicators of exploratory factor analysis, as well as Bartlett’s KMO and sphericity tests.

Table 9. Statistical Indicators of the Adjustment of the Exploratory Factor Analysis

|

Questionnaire |

Cronbach Alpha |

Explained Variance |

KMO Test |

Bartlett Test |

|

Benevolence |

0.874 |

67% |

0.850 |

p<0.00 |

|

Integrity |

0.905 |

68% |

0.850 |

p<0.00 |

|

Trust |

0.802 |

62% |

0.790 |

p<0.00 |

|

Leadership |

0.866 |

72% |

0.860 |

p<0.00 |

|

Employee |

0.853 |

69% |

0.800 |

p<0.00 |

|

Career |

0.926 |

77% |

0.880 |

p<0.00 |

Source:The result of the SPSS exploratory factor analysis

Results of the exploratory factor analysis lead to the conclusion that in all cases the questionnaires used have statistically significant reliability and validity indices. These parameters are explained through the factorial loads, the Cronbach’s alpha, the variance explained and the KMO and Bartlett tests (Field, 2013).

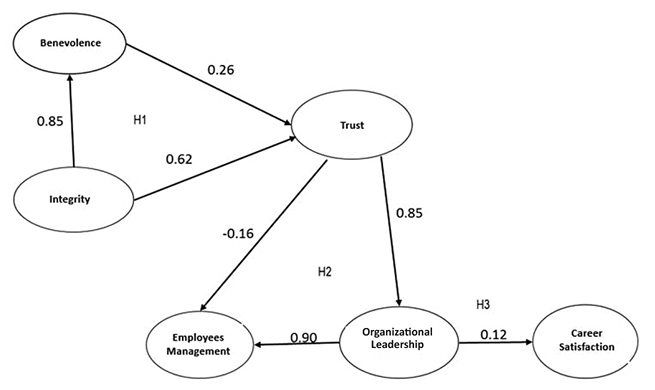

3. Model results

In order to evaluate the model of structural equations (SEM), Chi-square was considered as a first indicator (χ2 = 673.08 gl = 340), so the Chi-square test (χ2/gl = 1.97; p ≤ 0.001) was satisfactory. The indexes of comparative adjustments (TLI = 0.903 and CFI = 0.913) as well as the approximation of the square root of the mean squared error (RMSEA = .074) are within the accepted parameters for the validation of the model, so it turned out to be an absolutely desirable and acceptable model (Rigdon, 1996). The model realized through the AMOS 22 software is shown in Figure 3.

As shown in the model, there is a relationship between the variables studied and the human factor of the organizations. However, it is necessary to identify the loads of the regressions and evaluate their statistical significance as shown in Table 10 to approve or reject the hypotheses.

Figure 3. Results of the Structural Equation Model.

Source: Statistical analysis through AMOS 22

Table 10. Testing of Hypotheses and Their Main Indicators

|

Hypothesis |

Relationship |

Load of the |

P value |

Acceptance |

|

H1. There is a relationship between integrity, benevolence and trust perceived by workers in relation to their employers. |

Benevolence-Trust Integrity-Benevolence Integrity-Trust |

β = 0.26 β = 0.85 β = 0.62 |

< 0.005 < 0.0001 < 0.0001 |

H1 is accepted |

|

H2. There is a relationship between trust, leadership and employee management perceived by workers in relation to their employers. |

Trust-Leadership Trust-Employees Leadership-Employees Management |

β = 0.85

β = 0.90

|

< 0.0001 < 0.10 < 0.0001

|

H2 is accepted partially |

|

H3. There is a relationship between leadership and career satisfaction perceived by workers. |

Leadership –Career Satisfaction |

β = 0.12

|

< 0.05

|

H3 is accepted partially |

Source: The result of the SEM model

4. Conclusions

4.1 Theoretical implications

Through the review of the theoretical framework we realized that trust is an important factor to be considered in any type of relationship that exists between two people or between individuals and commercial entities or institutions. The relationships where trust intervenes are diverse in nature and can be personal, work or even virtual when a business relationship is established remotely. Trust is a factor that determines whether a person can establish a link simply with a handshake or must sign a strict contract where the parties commit to certain agreements.

The scope of the study of trust in our research is related to the Mexican professional worker in relation to his immediate boss. It is necessary to establish a relationship of trust so that there really exists leadership according to our results. But for this relationship of trust to be established, it is first necessary that there should be integrity on the part of the person who seeks to exercise leadership. In other words, according to the indicators evaluated, it is necessary to have a sense of justice, consistency between saying and acting, and ethical values. The relationship of trust then, is strengthened by integrity and benevolence. The benevolence, according to the items evaluated, is the good will that a manager has in relation to his employees. The present study presents a difference from the studies conducted by Mayer and Davis (1999) in the North American culture where it was found that there is a relationship between integrity, benevolence, ability and trust. The results of our study prove Hypothesis 1. Therefore, trust, benevolence and integrity should be promoted in the organization to achieve organizational climates that support leadership. In the recent study by Nedkovski, Guerci, De Battisti and Siletti (2017), the relationship between the practices of trust and benevolence is established for an ethical organizational climate that favors the development of employees.

Hypothesis 2 is related to trust in relation to organizational leadership practices and employee management. The results demonstrate a strong relationship between trust and leadership in such a way that trust is a key factor in establishing leadership. On the other hand, the style of leadership is closely related to the management of employees. However, the results show that there is a negative but significant relationship between trust and the management of employees. In other words, confidence influences leadership directly, but the leadership style apparently establishes the form of employee management. In this sense we could further investigate how a leadership in the field of our Latin American society is more influenced by trust. The present work supports the proposal by Baek and Jung (2015) that establishes a significant relationship between trust and the general organizational climate of the organization.

In relation to Hypothesis 3, we concluded that there is a weak relation between career satisfaction and the leadership perceived by the employees. In this sense, career satisfaction is a wider concept that involves personal goals and career expectations. It seems that manager´s leadership is more like a mediation variable, but this relationship must be widely studied in the future for a better understanding. Han (2010) studied the relation trust in peers, the leadership of the manager and career satisfaction, his study concluded that leadership partially mediates trust and career satisfactions. Our findings agree with his study.

The results of Mayer and Davis (1999) and those found in our study present a dilemma to be investigated: do cultural nature variables influence directly the concept of trust? Considering the results, we could see that there are significant differences for different cultural contexts. In their original model, Mayer and Davis (1999) found a relationship between trust, benevolence, integrity and ability, however, we couldn’t replicate this study. Then it is assumed that cultural factors could significantly affect the concept of trust in the leader and its results. As established in post-colonial studies, there is a difference between the leaders of other cultures such as that of Americans, and what we would consider is the Latin culture and, specifically, Mexican culture. Authors such as Aktas, Gelfand and Hanges (2016) have demonstrated these differences.

4.2 Practical Implications

This study has several implications for business managers and policy makers. Talent retention is essential for reaching business goals and preserving and developing strategies in changing markets. To meet standards of talent retention, employees must meet their career satisfactions goals. Career goals partially depend on how the organization interacts with their employees in relation with career expectations and leadership. Trust directly interacts with the leader through their performance. If the leader does not show integrity and benevolence, the employee will not trust in his behavior to reach better performance. As Bulinska and Bagienska (2018) established, trust is a fundamental element for sustainable development of organizations. The relationships of trust between the employer, the employee and the organization are complex, especially in Mexico. Due to the levels of corruption shown in the government and also in some private business (Stanfill et al., 2016), the employee usually does not trust easily at a first moment. The trust relationship must be developed over time and with consistent behavior between the leader and the employee. As Starnes, Truhon and McCarthy (2015) establish, leaders with personal agendas and desire of power that pursue only self-rewards or are incompetent would create barriers for building trust.

Thus, the decision makers and the human resource department of all organizations should include policies that reinforce the trust behaviors in their managers. These policies could establish some means for getting feedback from employees such as suggestion mailboxes, interviews, surveys, etc. The managers should show a congruent behavior of what they declare and how they act, because employees are aware of how their leaders act, especially these days when the use of social networks is empowered by technology, the millennial generation of employees are changing the face of business promoting different values which promote the human rights. Latkovij, Popoyska and Popovki (2016) found that the millennial employee promotes the honesty value, their study was done in an emerging country. However, there is no research about trust and millennials in Latin-American contexts. So far, the awareness is that societies are changing faster than would be expected (Leach-López, Leach & Lee, 2019), and globalization seems to be a factor to influence the models of conduct of business in emerging countries.

References

Abele, A. E., Hagmaier, T., & Spurk, D. (2016). Does Career Success Make You Happy? The Mediating Role of Multiple Subjective Success Evaluations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1615–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9662-4

Alfes, K., Shantz, A. D., Truss, C., & Soane, E. C. (2013). The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: a moderated mediation model. The international Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 330–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.679950

Aktas, M., Gelfand, M. J., & Hanges, P. J. (2016). Cultural tightness–looseness and perceptions of effective leadership. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(2), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115606802

Arrow, K. J. (1972). Gifts and exchanges. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 343–362. Doi: 10.1515/9781400853564.139

Ashnai, B., Henneberg, S. C., Naudé, P., & Francescucci, A. (2016). Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: An attitude–behavior–outcome model. Industrial Marketing Management, 52, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.020

Atkinson, S., & Butcher, D. (2003). Trust in managerial relationships. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(4), 282–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940310473064

Baek, Y. M., & Jung, C. S. (2015). Focusing the mediating role of institutional trust: How does interpersonal trust promote organizational commitment? The Social Science Journal, 52(4), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2014.10.005

Bass, B. M. (1997). Does the transactional–transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist, 52(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.52.2.130

Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How does social trust affect economic growth?. Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346–1368. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-78.4.1346

Blake, R. & Mouton J. (1985). The Managerial Grid III: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston, USA: Gulf Publishing Co.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Burke, C. S., Sims, D. E., Lazzara, E. H., & Salas, E. (2007). Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(6), 606–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.006

Bulińska-Stangrecka, H., & Bagieńska, A. (2018). Investigating the Links of Interpersonal Trust in Telecom Companies in Poland. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201806.0007.v1

Bulińska-Stangrecka, H., & Bagieńska, A. (2019). HR Practices for Supporting Interpersonal Trust and Its Consequences for Team Collaboration and Innovation. Sustainability, 11(16), 4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164423

Bustillo, I., Artecona, R., & Perrotti, D. (2018). Inequality and growth in Latin America: achievements and challenges. Working Paper, Group of 24 and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, New York.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2005). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. John Wiley & Sons.

Carter, D. R., DeChurch, L. A., Braun, M. T., & Contractor, N. S. (2015). Social network approaches to leadership: An integrative conceptual review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 597. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038922

Creed, W. D., & Miles, R. E. (1996). Trust in organizations. Trust in organizations: frontiers of theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 16–38.

De Clerq, D., Bouckenooghe, D., & Raja, U. (2019). A Person-Centered, Latent Profile Analysis of Psychological Capital. Australian Journal of Management, 44(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/03128962187751533

Denison, D. R., Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1995). Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral complexity in managerial leadership. Organization Science, 6(5), 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.5.524

Fiedler, F. E., & Garcia, J. E. (1987). New approaches to effective leadership: Cognitive resources and organizational performance. John Wiley & Sons.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

Flavian, C., Guinalíu, M., & Jordan, P. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of trust on a virtual team leader. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 28(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejmbe-11-2017-0043

Fox, J. (2002). Structural equation models. Appendix to an R and S-PLUS Companion to Applied Regression.

Gazdag, B. A., Haude, M., Hoegl, M., & Muethel, M. (2019). I Do Not Want to Trust You, but I Do: on the Relationship Between Trust Intent, Trusting Behavior, and Time Pressure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(5), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9597-y

Gillespie, N. A., & Mann, L. (2004). Transformational leadership and shared values: the building blocks of trust. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19, 588−607. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551507

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-55

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/256352

Harris, M. M., Anseel, F. & Lievens, F. (2008). Keeping up with the Joneses: a field study of the relationships among upward, lateral, and downward comparisons and pay level satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 665. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.665

Han, G. (2010). Trust and career satisfaction: The role of LMX. Career Development International, 15(5), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011075321

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1993). Management of Organizational Behaviour: Utilizing human resources. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/256741

Janssen, O. & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159587

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

Lavine, M. (2014). Paradoxical leadership and the competing values framework. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886314522510

Latkovikj, M. T., Popovska, M. B., & Popovski, V. (2016). Work values and preferences of the new workforce: HRM implications for Macedonian Millennial Generation. Journal of Advanced Management Science. https://doi.org/10.12720/joams.4.4.312-319

Leach-López, M. A., Leach, M. M., & Lee, E. (2019). Culture Convergence of Manufacturing Managers in Mexico, Korea, Hong Kong, and USA. Journal of Research in Emerging Markets, 1(2), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.30585/jrems.v1i2.334

Lewis, J. D., & Weingert, A. J. (1985). Social atomism, holism, and trust. The Sociological Quarterly, 26, 455−471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1985.tb00238.x

Luhmann, N. (2000). Familiarity, confidence, trust: Problems and alternatives. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, 6, 94–107.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.84.1.123

Mayseless, O., & Popper, M. (2019). Attachment and leadership: Review and new insights. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.08.003

Misztal, B. (2013). Trust in modern societies: The search for the bases of social order. US: John Wiley & Sons.

Nedkovski, V., Guerci, M., De Battisti, F., & Siletti, E. (2017). Organizational ethical climates and employee’s trust in colleagues, the supervisor, and the organization. Journal of Business Research, 71, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.004

Newman, A., Cooper, B., Holland, P., Miao, Q., & Teicher, J. (2019). How do industrial relations climate and union instrumentality enhance employee performance? The mediating effects of perceived job security and trust in management. Human Resource Management, 58(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21921

Northouse, P. G. (2013). Leadership: Theory and Practice. Sage publications.

Powell, W. W. (1995). Trust-Based Forms of Governance. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, 51. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243610.n4

Putnam, R. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 13(Spring), Vol. 4. Available online: http://www. prospect. org/print/vol/13 (accessed 7 April 2003).

Quijano, A. (1995). Raza, etnia y nación en Mariátegui: cuestiones abiertas. Estudios latinoamericanos, 2(3), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.22201/cela.24484946e.1995.3.49720

Quijano, A. (1999). Colonialidad del poder, cultura y conocimiento en América Latina. Dispositio, 24(51), 137–148.

Quinn, R. E., Bright, D., Faerman, S. R., Thompson, M. P., & McGrath, M. R. (2014). Becoming a master manager: A competing values approach. United States: John Wiley & Sons.

Radhakrishna, A. & Raju, R. S. (2015). A Study on the Effect of Human Resource Development on Employment Relations. IUP Journal of Management Research, 14(3), 28.

Rigdon, E. E. (1996). CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 3(4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519609540052

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Sánchez, C. M., & Lehnert, K. (2018). Firm-level trust in emerging markets: the moderating effect on the institutional strength-corruption relationship in Mexico and Peru. Estudios Gerenciales, 34(147), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.18046/j.estger.2018.147.2656

Sheppard, B. H. & Sherman, D. M. (1998). The grammars of trust: a model and general implications. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 422−437. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926619

Serva, M. A., Fuller, M. A. & Mayer, R. C. (2005). The reciprocal nature of trust: a longitudinal study of interacting teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 625−648. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.331

Stanfill, B. A., Villarreal, A. D., Medina, M. R., Esquivel, E. P., de la Rosa, E., & Duncan, P. A. (2016). Beyond the culture of corruption: Staying ethical while doing business in Latin America. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 20(SI 1), 56

Stranes, B., Truhon, S., McCarthy, V. (2015). Organizational Trust: Employee-Employer Relationships. A Primer on Organizational Trust. 2015. Available online: https://asq.org/hdl/201 0/06/a-primer-on-organizational-trust.pdf

Stogdill, Ralph. M. (1974). Handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research. NewYork, USA: Free Press.

Tzafrir, S. S., & Dolan, S. L. (2004). Trust me: a scale for measuring manager-employee trust. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 2(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/15365430480000505

Valizade, D., Ogbonnaya, C., Tregaskis, O. & Forde, C. (2016). A mutual gains perspective on workplace partnership: Employee outcomes and the mediating role of the employment relations climate. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12113

Vilkinas, T. & Cartan, G. (2006). The integrated competing values framework: Its spatial configuration. Journal of Management Development, 25(6), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1108/026217106106700922

Yu, M. C., Mai, Q., Tsai, S. B., & Dai, Y. (2018). An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship and innovative behavior from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability, 10(3), 864. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030864

Zevallos Vallejos, E. G. (2003). Micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas en América Latina. Revista de la CEPAL. https://doi.org/10.18356/da461f83-es