Lietuvos chirurgija ISSN 1392–0995 eISSN 1648–9942

2024, vol. 23(3), pp. 198–204 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/LietChirur.2024.23(3).6

Short-Term Outcomes of Totally Extraperitoneal and Extended Totally Extraperitoneal Repair of Ventral Hernia

Santosh D. Thorat

Department of Surgery, Yashwantrao Chavan Memorial Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India

E-mail: drsantosh308@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4801-4847

https://ror.org/01kxpxf76

Rajeev P. Bilaskar

Department of Surgery, Yashwantrao Chavan Memorial Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India

E-mail: rajeevbilaskar@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7288-4802

https://ror.org/01kxpxf76

Abstract. Since the beginning of surgical history, treatment of hernia has evolved through different stages. Belyansky et al. reported that this technique of e-TEP can also be applied for ventral hernia repair in 2017. The retro muscular e-TEP/e-RS approach combines the advantages of the sublay position of the mesh along with the benefits of the minimal invasiveness of the procedure. A prospective observational study was conducted among 60 patients with non-complicated ventral hernia who were randomised into two groups, equally, who were further subjected to either TEP or e-TEP laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Distribution of median duration of surgery for among the cases studied was significantly higher in Laparoscopic e-TEP repair group as compared to Laparoscopic TEP repair group. e-TEP has advantage over TEP owing to less steeper learning curve, with wide angle view, more degree of movements for instruments, and ergonomically better operative experience.

Keywords: TEP, e-TEP, ventral hernia, minimal access surgery.

Received: 2024-05-14. Accepted: 2024-06-21.

Copyright © 2024 Santosh D. Thorat, Rajeev P. Bilaskar. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

LVHR (laparoscopic ventral hernia repair) follows Pascal’s law and involves either intra-peritoneal onlay or pre peritoneal mesh placement as in TEP and e-TEP technique of hernia repair. There is a mechanical superiority of mesh placement in the preperitoneal or retro-muscular space [1–3]. The International Endo hernia Society (IEHS) Guidelines suggests that laparoscopic preperitoneal abdominal wall hernia repair by totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair techniques in small and medium-sized primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias is feasible and has minimal morbidity. The advantages are: 1) cost-effective due to use of standard polypropylene mesh, 2) hernia sac excised and removed, 3) mesh is extra-peritoneal, 4) the defect is closed and the abdominal wall reconstructed anatomically. However, the technique is more demanding in terms of increased intraoperative time, steep learning curve [4]. The extraperitoneal approach does not involve entry in the abdominal cavity reducing the risk of intestinal and vascular injuries as well as herniation at the trocar sites [5, 6]. Additionally the port placements in TEP for ventral hernia technique are nearer to the hernia so that less dissection has to be carried out in the previously unexplored extraperitoneal space and hence less chance of further stress on the already weakened posterior rectus sheath in case of a ventral hernia.

In 2012, Daes [7] described the extended-view TEP (e-TEP) technique, which resolved the ergonomic problems by expanding the vision of the operating field. In 2017 Belyansky published the totally-extraperitoneal access for the correction of ventral hernias, which reproduced the technique described by Rives and Stoppa for endoscopic retro muscular repair [8]. The Key Technical Aspects of e-TEP are: 1) High Camera Port Placement, 2) Division of the Posterior Fascia. Even though there is rapid development in the field of minimally invasive surgery in hernia repair, general surgeons have not yet developed an ideal or a standard method that has significantly reduced the postoperative complications such as SSI, recurrence of the hernia, and pain [9].

The preperitoneal space lies in between the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia. TEP repair is a relatively new technique where the dissection and repair are carried out without entering the peritoneal cavity. McKernan and Law [10] first introduced TEP hernia repair in 1993. It requires the creation of a space that allows insertion of a mesh. The ports are placed near to the hernia so that it reduces the dissection in the extraperitoneal space. The genesis of the preperitoneal space belongs to the in toto genesis of the abdominal wall. The preperitoneal space and its extensions between the inguinal ligament below and the diaphragm above are formed “by necessity” to permit the downward and upward transmission of anatomic structures, such as arteries, veins, lymphatics, nerves, spermatic cord, and ureters [11].

Patient and Methodology

A prospective observational cross-sectional study of 60 patients diagnosed with ventral hernia and randomly subjected to laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) either by TEP or e-TEP technique. Two groups of 30 patients each as:

Group 1. Laparoscopic TEP hernia repair.

Group 2. Laparoscopic e-TEP hernia repair.

Random allocation of patients was done in two groups using block randomization (creating blocks of 4 subjects each) using an allocation ratio of 1:1 for each group. Study was conducted according to IEC (Institutional Ethics Committee) guidelines over a period of 18 months. Registration No. ECR/1236/INST/MH/2019. Reference No. IECPGI-08/2021. The aim of the study was to observe – clinical outcomes of both the approaches to ventral hernia repair, to explore the lesser driven roads in case of TEP approach in ventral hernia.

All patients more than 18 years of age presenting with ventral hernia to surgery OPD. To study the two approaches for hernia surgery with respect to: duration of surgery, duration of hospital stays (days), time to return to daily activities (days), intra operative difficulties, post-operative pain and post-operative complications immediate, early and late. Inclusion criteria was patients diagnosed with ventral hernia, defect size <10 cm and patients above 18 years of age of either sex. Exclusion criteria were patients with complicated hernias like obstructed or strangulated hernias or patients with peritonitis, patients with predisposing factors for recurrence viz COPD, BEP, cases in which general anaesthesia was contraindicated, defect size >10 cm. After obtaining informed consent, a detailed history was obtained. A thorough clinical examination including general physical examination and systemic examination was carried out. Investigations required for pre-anaesthetic check-up and other relevant investigations were done. Patients posted for surgery received similar perioperative management. Polyproplene medium weight mesh with 5 cm margins around the defect was used in both the groups. In the entire study, the p-values less than 0.05 are statistically significant. The data was analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0, IBM Corporation, USA) for MS Windows [12–14].

1. Laparoscopic Totally Extra peritoneal (TEP) ventral hernia repair

The patient was placed in supine position with both hands tucked in. Operating surgeon, the assistant and nursing staff on the same side of surgeon, and monitors at the opposite side of the patient. After painting and draping, skin markings are done for sites of trocar insertion.

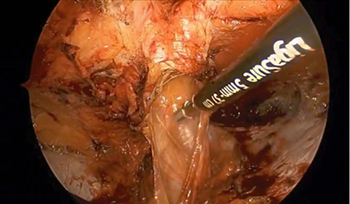

An 10 mm incision is made on the skin on either of the side of the mid line ventral hernia, then the anterior rectus sheath is incised and lips of incised sheath are secured with polyglactin sutures, the ipsilateral rectus abdominis muscle is retracted laterally, and blunt dissection is used to create a space beneath the rectus muscle. The space is then insufflated, and additional two 5 mm working trocars are put in. Initially for few surgeries zero-degree laparoscope was used first and later on 30-degree laparoscope was used. In TEP the working ports are placed as close to the hernia defect as possible so as to prevent excessive dissection over the posterior rectus sheath which is already weakened (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. A. B

Once the space is created, two 5 mm working ports come into play. Minimal dissection into the right plane with crossover takes place. The crossover begins form the margin of the hernia defect in either direction for limited length. The sac is identified, opened at specific point, the contents are inspected and reduced under vision. The defect is then closed with the help of continuous v-lock (barb) sutures.

The mesh of appropriate size is then introduced the 10 mm trocar by book fold technique. Confirmation of proper placement of mesh is done by deflation and inflation test. Anterior rectus sheath is closed with 2–0 polyglactin. Skin closure is done with 3–0 subcuticular poliglecaprone (Monocryl) sutures (Figures 2, 3).

2  3

3

Figures 2

Figures 3

2. Laparoscopic extended-Totally Extra peritoneal (e-TEP) ventral hernia repair

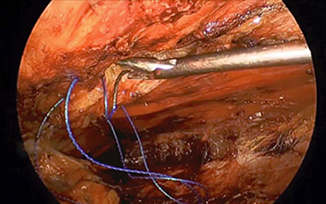

The patient was placed in supine position with both hands tucked in. The operating surgeon stands on side of patients, the assistant cranial to the surgeon and nursing staff on the same side of surgeon, the monitors at the opposite side of the patient. After painting and draping skin markings are done for sites of trocar insertion (Figure 1B).

A 10 mm incision is made on the skin on one side of the mid line ventral hernia near the xiphoid process within the laterally placed semilunar line, then the anterior rectus sheath is incised and lips of incised sheath are secured with polyglactin sutures, the ipsilateral rectus abdominis muscle is retracted laterally, and blunt dissection is used to create a space beneath the rectus muscle. Working ports to be placed according to the ergonomic convenience of surgeon. The ports are placed far from the hernia especially the camera port to achieve the enhanced view but at the cost of excessive dissection to reach the hernia site.

The posterior rectus sheet is dissected with two 5 mm working ports to establish a cross over to the other side thus to create an enhanced or extended view of the space created. Here the crossover begins far from the defect and is in the direction of the defect. Additional working port can be inserted on the ipsilateral side. The sac is identified, opened, the contents are inspected and reduced under vision. The defect is then closed with the help of continuous v- lock (barb) sutures. A polypropylene mesh customized to size is introduced the 10 mm trocar by book fold technique and placed flat behind the rectus muscle. All ports are closed with subcuticular sutures with monocryl sutures. Patients were followed in wards and hospital outpatient clinic at 1 week, 1 month and 6 months.

Results

Out of 60 cases under study 32% cases had primary umbilical hernia – M3 23% cases had primary paraumbilical hernia – M3 Primary epigastric hernia consisted of 15% of the total cases under study – M1 Incisional hernia accounted for 30% of the total cases predominantly of M4 type. Maximum number of cases, that is 23 out of 60 (76.7%), were in the age group of 41–60 years. Out of total 30 cases, in the TEP group epigastric hernia accounted 13.30%, umbilical and paraumbilical hernia 10% and incisional accounted for 20%. Distribution for 30 cases under e-TEP was – umbilical 30%, paraumbilical 13.3%, epigastric 20% and lastly incisional 40% (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic data

|

TEP |

e-TEP |

||

|

Age |

21–40 41–60 61–80 81–100 |

14 (46.7%) 9 (30.0%) 7 (23.3%) 0 (0%) |

6 (20%) 14 (46.7%) 9 (30.0%) 1 (3.3%) |

|

Type of |

Epigastric Umbilical Paraumbilical Incisional |

4 (13.3%) 10 (33.3%) 10 (33.3%) 6 (20.3%) |

5 (16.7%) 9 (30.0%) 4 (13.3%) 12 (40.0%) |

|

Duration of |

8.0 (median) |

6.5 (median) |

|

The median duration of symptom – swelling over abdomen was 8 months in case of patients who had undergone TEP repair. Median duration for e-TEP was 6.5 months. Longer the duration of patients withholding a hernia greater the chance of adhesion of the hernia sac and hence increased skill of dissection required at the cost of intraoperative time. The range of duration of symptoms of hernia in TEP and e-TEP repair group was 3–24 months and 2–18 months, respectively. Distribution of median duration of hernia among the cases studied did not differ significantly between two study groups (p > 0.05).

The median duration of surgery among the cases studied in TEP and e-TEP repair was 99 min. and 110 min., respectively. The range of duration of surgery in TEP and e-TEP repair was 90–127 min. and 90–134 min., respectively. In the TEP repair group, 3 (10.0%) had to be converted to open ventral hernia repair. It was 4 (6.6%) Laparoscopic e-TEP repair group. The distribution of conversion among the cases studied did not differ statistically (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Perioperative finding

|

TEP |

e-TEP |

|

|

Duration of surgery Accidental pneumoperitoneum Conversion rate to open hernioplasty Visceral injury Vascular injury SSI Seroma Mesh infection Post op pain Duration of hospital stay Time of return to daily activities |

99.0 (median) n = 4 (13.4%) n = 3 (10.0%) 0 0 1 (3.4%) 3 (10.0) 0 2.0 (median) 2.0 (median) 4.0 (median) |

110.0 (median) n = 2 (6.6%) n = 2 (6.6%) 0 0 2 (6.6%) 4 (13.4) 0 2.0 (median) 2.0 (median) 3.0 (median) |

In the Laparoscopic TEP repair group, 4 cases (13.4%) had to use a Veress needle for control of accidental pneumoperitoneum. 2 (6.6%) cases required Veress needle in e-TEP repair group. The distribution of conversion among the cases studied did not differ significantly between two study groups (p > 0.05). There was no incidence of vascular or visceral injuries among all the 60 cases operated laparoscopically. The median duration of post-operative pain among the cases studied in TEP and e-TEP repair was 2 days in both the intervention. The range of duration of surgery for site in TEP and e-TEP repair was 1–4 days in both the groups. However, the differences for both the groups studied was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

The median duration of hospital stay in both the group was 2 days. With range of 1–4 days in TEP group and range of 1–5 in e-TEP group. 11.6% of the total cases operated had seroma post operatively. Of 30 cases studied in TEP repair group, 3 (10.0%) had seroma post operatively. Of 30 cases studied in e-TEP repair group 4 (13.4%) had seroma or hematoma post operatively. Of 30 cases studied in TEP repair group, 29 (96.6%) did not have superficial wound infection and 1 (3.4%) had superficial wound infection. In the e-TEP repair group, 2 (6.6%) had superficial wound infection. Overall, incidence of SSI was 5%. Median days to return to daily activity in TEP vs. e-TEP is 4 and 3 respectively. The difference is not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The evolution of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair has been protracted due to the long learning curve. Despite many comparative studies, a consensus has not been reached over the best technique of ventral hernia repair. Maximum number of cases – 23 out of 60 were in the age group of 41–60 years. This coincides with the peak period of the worker’s heavy job. In the present study mean age was 48.28 years (standard deviation – 13.92). In Belyansky et al. [8] study mean age was 54.9 years. It was 49.34 years in Prakhar et al. [15].

The median time for laparoscopic TEP repair of ventral hernia was 99 min. and for e-TEP was 110 min. respectively. The range was 90–127 min. and 90–134 min. respectively. Distribution of median duration of surgery for among the cases studied was significantly higher in Laparoscopic e-TEP repair group as compared to TEP repair group. Laparoscopic TEP repair is a more complex procedure with a steeper learning curve than e-TEP repair. Studies have concluded that laparoscopic hernia repair should be carried out by a surgeon who has a specialized training in performing this procedure [16, 17]. In Belyansky et al. [8] mean intraoperative time was 218.9±111.2 min. Mean intraoperative time was 113.08±63.30 min. in Baig et al. [18]. It was 113.08±63.30 min. in Prakhar et al. [17].

Sudarshan et al. [19] 2021 reported 16% use of Veress needle for management of pneumoperitoneum in TEP inguinal hernia repair. Introduction of Veress needle into the intraabdominal cavity is used as to tackle the rents in the peritoneum during dissection. Initially due to steep learning curve and limited ergonomics and introduction to these newer techniques of hernia repair, accidental rents in the peritoneum are anticipated. 13.4% of TEP group had to depend on it to tackle pneumoperitoneum. It was 6.6% in the e-TEP cases. However, the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The shorter the hospital stay, lower is incidence of hospital acquired infection [20]. The median duration of hospital stay in both the group was 2 days and was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Baig et al. [18] median duration of hospital stay was 3 (Table 2).

In the study, 10% of the cases who underwent TEP repair had seroma post operatively. It was 13.4% in the e-TEP group. However, the comparison was statistically not significant (p > 0.05). 11.6% of the total 60 patients reported to have seroma. In Belyansky et al. [8] retrospective study incidence of seroma was 2.5%. It was 2.34% in Prakhar et al. [15].

Incidence of SSI was 5% in this study. 3.3% in TEP and 6.6% in e-TEP ventral hernia repair respectively. In Belyansky et al. [8] retrospective study incidence of SSI was 0%. As per Baig et al. [18] SSI was 0%. It was 2.94% in Prakhar et al. [15]. In our study the mean duration of time to return to daily activities is 3.6176. It was 4 days (mean) in Ngo et al. [21].

Conclusion

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair by e-TEP is technically easy to learn as compared to TEP. Also, it is ergonomically convenient and allows flexibility of port placement. Conversion rate to open surgery was less in e-TEP as compared to TEP but not statistically significant. Use of verese needle is less frequent in e-TEP repair. TEP has a steep learning curve as compared to e-TEP. Most of these shortcomings can be minimized once the surgeon gains enough experience and enters the plateau phase of the learning curve. Thus, from our study we conclude that laparoscopic e-TEP hernia repair is better modality of treatment for uncomplicated reducible ventral hernias in terms of wider working space, less conversion rates and lenient learning curve. However, learning and unlearning is part and parcel of surgeon’s life and when need arises the surgeon should withstand the challenges of complex hernia with the simplicity of newer and more rational technique of surgery.

Limitations. A large size RCT would help us better in comparing the outcomes of the study and would definitely help us in understanding various aspects of the procedure in detail.

Author Contribution. Dr. Santosh D. Thorat – study concept and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical review of manuscript. Dr. Rajeev P. Bilaskar – acquisition of data analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of manuscript.

No Funding.

Declarations

Ethics Approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of Interest. The authors declare no competing interests.

Referenc es

1. Penchev D, Kotashev G, Mutafchiyski V. Endoscopic enhanced-view totally extraperitoneal retromuscular approach for ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 2019; 33(11): 3749−3756.

2. Stoppa RE. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg 1989; 13(5): 545–554.

3. Wantz GE. Incisional hernioplasty with Mersilene. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1991; 172(2): 129–137.

4. Bittner R, Bingener-Casey J, Dietz U, Fabian M, Ferzli G, Fortelny R, Köckerling F, Kukleta J, LeBlanc K, Lomanto D, Misra M, Morales-Conde S, Ramshaw B, Reipold W, Rim S, Rohr M, Schrittwieser R, Simon T, Smietanski M, Stechemesser B, Timoney M, Chowbey P. Guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias (International Endohernia Society [IEHS]) – Part III. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 380–404. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-013-3172-4.

5. Wake BL, McCormack K, Fraser C, Vale L, Perez J, Grant AM. Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) vs totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. DOI: 10.1089/lap.2008.0212.

6. Leibl BJ, Jäger C, Kraft B, Kraft K, Swartz J, Ulrich M, Bittner R. Laparoscopic hernia repair – TAPP or/and TEP? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2005; 390(2): 77–82.

7. Daes J. The enhanced view-totally extraperitoneal technique for repair of inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 2012; 26(4): 1187–1189.

8. Belyansky I, Daes J, Radu VG, Balasubramanian R, Reza Zahiri H, Weltz AS, Sibia US, Park A, Novitsky Y. A novel approach using the enhanced-view totally extraperitoneal (eTEP) technique for laparoscopic retromuscular hernia repair. Surg Endosc 2018; 32(3): 1525–1532.

9. Vorst AL, Kaoutzanis C, Carbonell AM, Franz MG. Evolution and advances in laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(11): 293−305.

10. McKernan JB, Laws HL. Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias using a totally extraperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg Endosc 1993; 7(1): 26–28.

11. Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, Skandalakis LJ. The embryology of the inguinofemoral area: an overview. Hernia 1997; 1: 45–54.

12. Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics, 5th edition. Duxbury, 2000, p. 80–240.

13. Riffenburg RH. Statistics in Medicine, 2nd edition. Academic Press, 2005, p. 85–125.

14. Sunder Rao P, Richard J. An Introduction to Biostatistics: A Manual for Students in Health Sciences, 4th edition. New Delhi: Prentice Hall of India, 2006, p. 86–160.

15. Prakhar G, Parthasarathi R, Cumar B, Subbaiah R, Nalankilli VP, Praveen Raj P, Palanivelu C. Extended view: totally extra peritoneal (e-TEP) approach for ventral and incisional hernia – early results from a single center. Surg Endosc 2021; 35(5): 2005–2013. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-020-07595-4.

16. Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J, Reda D, Henderson W, Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 456 Investigators. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(18): 1819–1827.

17. Is laparoscopic groin hernia repair better than open mesh repair? The Internet Journal of Surgery 2006; 8(2).

18. Baig SJ, Priya P. Extended totally extraperitoneal repair (eTEP) for ventral hernias: short-term results from a single centre. J Min Access Surg 2019; 15(3): 198–203.

19. Sudarshan PB, Packiaraj GD, Papa T, Porchelvan S, Kumaran K, Selvam A, Sundaravadanan BS. A comparative study of extended view – totally extraperitoneal repair versus totally extraperitoneal repair for laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery. IJSS Journal of Surgery 2021; 7(5): 50–54.

20. McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, Ross S, Grant AM; EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration Affiliations. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003; 2003(1): CD001785.

21. Ngo P, Cossa JP, Largenton C, Johanet H, Gueroult S, Pélissier E. Ventral hernia repair by totally extraperitoneal approach (VTEP): technique description and feasibility study. Surg Endosc 2021; 35(3): 1370–1377. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-020-07519-2.