Kalbotyra ISSN 1392-1517 eISSN 2029-8315

2024 (77) 7–46 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Kalbotyra.2024.77.1

Papers

Johan van der Auwera

Linguistics

University of Antwerp

Prinsstraat 13

B-2000 Antwerp, Belgium

E-mail: johan.vanderauwera@uantwerpen.be

[...] any, without any doubt the world’s best-known, and most

intensively studied polarity item (Hoeksema 2010b, 188)

Abstract. Since Ladusaw (1979) the term ‘free choice indefinite’ is the generally accepted term for the meaning of any in primarily modal and generic sentences, such as Any owl hunts mice, but not for what is generally called the ‘polarity-sensitive’ or ‘negative polarity’ meaning, as in Did you take any? At least part of the inspiration for Ladusaw was Vendler (1967), but Vendler took a notion of ‘freedom of choice’ to characterize all uses of any. This paper has three goals: (i) to offer a critical survey, updating earlier ones by Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005) of the question whether English any has one meaning – a univocal account – or two – an ambiguist account, with the two alleged meanings involving negative polarity, on the one hand, and free choice, on the other hand; (ii) to confirm, in agreement with much current work, that Vendler (1967) was right, and to suggest, in disagreement with most if not all current work, to make terminology reflect the insight and no longer restrict the term ‘free choice’ to just a few of the meanings of any; and (iii) to offer a new univocal approach of any, hypothesizing its meaning to contain the components ‘existence’ and ‘free choice’, and using the notion of ‘at-issueness’.

Keywords: free choice, negative polarity, indefiniteness, at-issueness, non-veridicality, widening, scalarity

1 Introduction

This paper deals with the role of the notion of ‘free choice’ in the analysis of English any. Section 2 is about the difference between the approaches of Vendler (1962, 1967a, 1967b) and Ladusaw (1979) and the way later researchers dealt with this difference. Section 3 is a critical survey, in the spirit of Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005), of the question whether English any has one meaning – a univocal account – or two – an ambiguist account, with the two alleged meanings involving negative polarity, on the one hand, and free choice, on the other. Section 4 is a discussion of the three types of univocal accounts found in the literature. In section 5 I present my own univocal account, more particularly an account that takes free choice to be one of two components of the ‘core meaning’ of each use of any, the other one being existence. This univocal account allows any to have a plurality of ‘constructional meanings’, in which the core meaning components interact with the context in terms of being at issue or not at issue. Section 6 is the conclusion.

It is important to make clear the limitations of the present study. I only discus any in present-day Standard English, so not the any of other Englishes or related languages, like English Creoles or other West-Germanic languages, or of Old or Middle English (cf. Hoeksema 2010a; van der Auwera & Van Alsenoy 2013, van der Auwera 2017). I only discuss the pronoun and the determiner any, so not the adverbs or discourse markers anyhow or anyway, nor the use of any with comparatives or the comparative-derived adverb anymore (see Hoeksema 2010b, 56–59). Furthermore, this paper only deals with semantics, not with syntactic, psycholinguistic or sociolinguistic issues. Last but not least, though this paper discusses a fair amount of hypotheses, the magnitude of the literature is such that there is no pretence to have covered all relevant observations and issues.

2 Vendler (1962, 1967a, 19767b) vs. Ladusaw (1979)

The current use of the term ‘free choice’ is indirectly due to an article by Zeno Vendler in the journal Mind, a journal of psychology and philosophy (Vendler 1962). The indirectness has four sides to it. First, most linguists do not refer to the 1962 article, but instead to a chapter in Vendler’s 1967 book Linguistics in Philosophy (Vendler 1967b, 70–96). The latter combines the 1962 article with some paragraphs of a contribution of Vendler’s on any and all in an encyclopaedia of philosophy (Vendler 1967a). Second, the term ‘free choice’ does not occur in any of these publications, instead we find ‘freedom of choice’ (Vendler 1962, 151; 1967a, 132; 1967b, 80). Third, ‘free choice’ probably first appears in Ladusaw (1979): Ladusaw refers to Vendler (1967b), but not to Vendler’s term ‘freedom of choice’. The way Ladusaw introduces the term ‘free choice’ makes clear that he assumes the responsibility. The italics in the quotations below are mine.

The semanticists […] are principally interested in being able to account for the meaning of any when used in sentences like (9a), (which I shall refer to as free-choice (FC-) any) […]

(9)a. John will dance with anyone.

(Ladusaw 1979, 94)

In this section I will briefly discuss what I have termed Free-choice any.

(Ladusaw 1979, 104)

Fourth, Ladusaw’s phrase ‘free choice’ (later also spelled ‘free-choice’ and ‘Free-choice) is obviously very similar to Vendler’s ‘freedom of choice’ and one might think that the distinction is stylistic only. But, importantly, Vendler and Ladusaw give the term(s) a different meaning.1 For Vendler ‘freedom of choice’ is a property of all uses of English any and it is intended, pace Tovena (1998, 156), as an improvement over thinking of any as a kind of universal quantifier. (1) lists some of Vendler’s (1967b) examples for the various uses of any.

(1) Vendler (1967b, 70, 80, 87, 81, 83, 90)

a. Any doctor will tell you what to do.

b. I can beat any of you.

c. Anybody who is my friend smokes a pipe.

d. Did you take any?

e. If you ask any doctor, he will tell you …

f. I didn’t see any pigs in the pen.

Ladusaw’s ‘free choice’ only applies to examples (1)a–c, not to (1)d–f, the uses in interrogative, conditional or negative sentences. In the latter type of sentences, Ladusaw sees a different any, a ‘polarity-sensitive’ any, more often called ‘negative polarity’ any (after Baker 1970, 170). Thus any joined a wider set of negative polarity items, all of which are allowed in contexts in which they are ‘licenced’ or ‘triggered’ by certain operators (like negation). These issues had been debated for some time (Klima 1964) and Ladusaw proposed a semantic characterization of these contexts. His hypothesis proved very important (see e.g. Gajewski 2022), even though it does not quite work. The idea is that the contexts in which the licenser and the licensee occur have the semantic property of allowing inferences from sets to subsets – they are supposed to be ‘downward entailing’. This works for negative sentences.

(2) I didn’t see any pigs in the pen.

⊃ I didn’t see any small pigs in the pen.

It works for other contexts, as with the quantifier few or the conjunction before.

(3) Few of us saw any pigs in the pen.

⊃ Few of us saw any small pigs in the pen.

(4) He left left before he saw any pigs in the pen.

⊃ He left before he saw any small pigs in the pen.

But it does not work or not without problems for the Vendler contexts that are taken to contain negative polarity items and that are illustrated in (1)d-e. Questions are not in any obvious way downward entailing and neither are conditionals, for different reasons (Van der Wouden 1997, 162–163, 159; Giannakidou 1998, 11–12, 130; Israel 2004, 718).

(5) Did you take any drugs?

⊅ Did you take any expensive drugs?

(6) If you take any trip to Yemen, you will enjoy it.

⊅ If you take any trip to Yemen and get sick there, you will enjoy it.

On the analysis of the any’s in (1)a–c, Ladusaw has little to offer and what he does say shows some uncertainty. On the one hand, he finds it “quite plausible” (Ladusaw 1979, 94-95) to analyse the any of (1)a–c as a special use of a universal quantifier (a wide-scope use), as argued by the logicians Reichenbach (1947) and Quine (1960) earlier and Ladusaw’s near-contemporaneous generative grammarians (Lasnik 1972; LeGrand 1974, 1975; Kroch 1974). On the other hand, he finds this approach “unsatisfactory […] in the long run” (Ladusaw 1979, 104) and he is sympathetic to Vendler’s notion of choice, but only for examples (1)a–c. To basically steer clear of the issues involved by examples (1)a–c is a fully acceptable decision, of course. It is less acceptable that he does not justify using the term ‘free choice’ for only some uses, when there is a near-namesake that Vendler intended for all uses of any. What happens later is that the term ‘free choice’ will become prominent in the Ladusaw use. This is fine, if his double any approach would get the upper hand over Vendler’s single any approach. But, as we will see, this is not the case. The majority of linguists will, sometimes unknowingly, return to Vendler and claim that free choice characterizes all uses. But even then, the Ladusaw terminology will stay and we have the terminologically infelicitous situation in which both free choice uses and non-free choice uses – with ‘free choice’ in the Ladusaw sense – are characterized by ‘free choice’ – in the Vendler sense. In my view, Ladusaw’s ‘long run’ has run long enough. I will henceforth use ‘free choice’ only in the Vendler sense.2 The ‘free choice’ uses in (1)a–c with the Ladusaw sense of ‘free choice’ will be called ‘quasi-universalist’ (for short, ‘Q∀’)3, to reflect that these uses of any show a similarity to those of the universal quantifier. This similarity can be appreciated by comparing (1)a–c to (7)a–c.

(7) a. Every doctor will tell you what to do.

b. I can beat all of you.

c. Everybody who is my friend smokes a pipe.

The non-universalist uses in (1)d–f will be called ‘quasi-existentialist’ (for short, ‘Q∃’), to reflect that these uses betray a similarity to the existential quantifier, as can be appreciated by comparing (1)d–f to (8)a–c.

(8) a. Did you you take some?

b. If there is a/some doctor and you ask him, he will tell you that …

c. I didn’t see pigs / a pig in the pen.

As a side note, the diagnostic for distinguishing Q∀ and Q∃ uses is thus the paraphrasability just demonstrated. Several other diagnostics have been proposed, but they all seem worse. The best one might have been the almost test, judged to be compatible with Q∀ uses but not Q∃ ones (Carlson 1980, 803; 1981, 9; Hoeksema 1983, 409; Haspelmath 1997, 93; Horn 2000b, 161; Chung 2010, 141; Sohng 2014, 141; Giannakidou 2018, 508), but as Horn (2005, 193–199) points out, the diagnostic is not reliable.

3 One or two any’s?

Ladusaw’s 1979 work was very influential, for the study of negative polarity in general as well as for the study of English any. For any Ladusaw made linguists more aware and even very aware that there might be two any’s. There was some awareness before. Thus Horn has characterized this issue on at least three occasions (Horn 2000a, 2000b, 2005) and he points out that this debate, called ‘perennial’ (Horn 2000b, 158), goes back to at least the middle of the nineteenth century, opposing Augustus De Morgan ([1862]1966, 275) to William Hamilton (1858, 615). Horn categorizes linguists (and logicians) in two camps, viz. the ambiguist view and the ‘(quasi-)univocal’ view (Horn 2000a, 79; 2000b, 169) – note the double hedge, ‘quasi’ and the brackets around ‘quasi’. Below I will redo this classification, but not in two groups but in four. First, I distinguish a group of scholars who withhold judgment, either because they are undecided or decidedly neutral. Second, I split Horn’s ‘(quasi-)univocal’ group into two groups, viz. one for scholars that unreservedly go for a univocal position and one for scholars that have some reservations. The best example of a hedged endorsement of is that of Horn himself.

On this view, any is more or less always an indefinite-plus, whose use is bound up with some aspect of the hearer’s free choice in identifying referents or witnesses to fill out the propositions. (Horn 2000b, 168, emphasis mine)

It is not always easy to decide where to put a scholar. What is one to do with Dayal (1998, 466)?

I will argue on the basis of language internal and crosslinguistic evidence that FC [free choice] and PS [polarity sensitive] any are distinct lexical items. I will, however, attempt to tie the two together by means of a common core of meaning.

It must be on the basis of the first sentence that Giannakidou (2001, 717), Farkas (2005, 79), Horn (2005, 181) and Israel (2011, 164) classify Dayal (1998) as an ambiguist. However, the two sentences quoted are followed by the following one (emphasis mine):

Such a quasi-univocal account would explain why a single lexical item in unrelated languages can have the same range of meanings as English any.

So Dayal (1995, 1998) should be put in the ‘quasi’ group – and this also what Horn did a few years earlier (2000b, 169), when he characterized Dayal (1995) as ‘basically’ univocal, which also accords well with her own 2004 paper.

One could imagine a few more groups. First, there could be scholars who take the debate to be about a non-issue. But I see no evidence for anybody holding this view. Second, in theory, the ambiguity group could be split up, for the ambiguist position is sometimes described as homophony (Chung 2010, 257) and accidental homonymy (Horn 2000b, 172). These terms are better avoided. There is an awareness of the claim mentioned in the ‘third sentence’ of Dayal’s (1998, 466). More particularly, researchers (e.g. Israel 2011, 23–24, 173; Chierchia 2013, 57) are aware of the typological generalization of Haspelmath’s (1997, 117): about half of the 40 languages studied in detail have one item covering both Q∀ and Q∃ uses (cp. also Forker 2016, 79–81). English is, of course, such a language, though the similarity between these languages should not be exaggerated: of the twenty languages maximally three may have any-like items with exactly the same range of uses. In any case, the ambiguist position is one that declares there to be two lexical items, but related ones. A third reason why there could be additional groupings relates to Haspelmath’s (1997) semantic map for indefinite pronouns, which distinguishes no less than nine uses. Haspelmath (1997, 59) remains uncommitted as to whether these ‘uses’ are actually ‘meanings’. Dayal (1998), for one, takes them to be meanings – see Dayal’s third sentence again – and so do I, as will be explicated in section 4 in terms of a distinction between core meaning and constructional meaning. In any case, of the nine uses/meanings any covers six. So there could have been a linguist who declares any to be six-way ambiguous (or, better, polysemous), but nobody has taken up this position.4

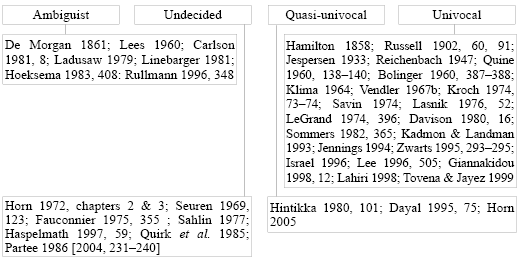

The four groups are shown in Figure 1. With the exception of Horn (1972), listed because of its ground-breaking character, I only mention work that is published5 and only one publication for each scholar, given that scholars didn’t generally6 change their mind. When there are succinct endorsements, I give the pages. For each category I mostly categorize work that was also categorized by Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005) and there are no strong discrepancies between our categorizations, except, of course, that I split up his (quasi-)univocal group and I have a group of the non-committed scholars.7 I do categorize a few works not dealt with in Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005) and, like in Horn, my lists do not include work that only deals with one of the two meanings or uses.8

Figure 1. One any vs. two any’s – a survey based on Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005)

The lists in Figure 1 are not meant to be exhaustive and neither were the ones offered by Horn. Thus Horn (2000a, 81; 2000b, 168) mentions that he holds the monoguist view to be adopted also in traditional dictionaries, such as the The Oxford English Dictionary, which gives any only one lemma. This comment needs to be checked, since Seuren (1969, 123) makes the opposite comment and Seuren furthermore claims that ‘most […] handbooks of grammar tend to distinguish two different any’s’. At least for Jespersen (1897, 50–51; 1949, 601), Poutsma (1916, 1036), Kruisinga (1925, 234), Quirk et al. (1991, 345), Greenbaum (1996, 192–193) and Huddleston & Pullum (2002, 380–383) Seuren is wrong. So these grammarians ‘reinforce’ the univocal camp and, even though the listing is not exhaustive, it would seem that at least up to the Horn surveys most scholars adopted the univocal view.

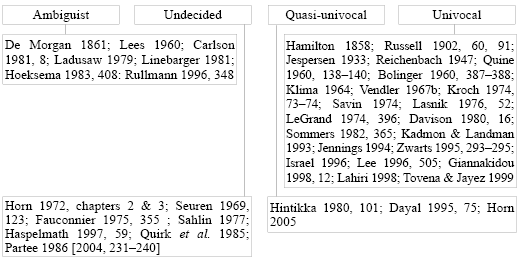

The work on any did not end when Horn last surveyed the field. In Figure 2 I chart some of the later studies. I again only list one publication for every scholar and I only list published work. To the extent that I can see, nearly everybody has made up his or her mind and there are no more ‘quasi-univocal’ accounts. There is, however, one scholar who is leaning towards indifference. Giannakidou (2001, 731) first defends a univocal account, but she concludes her study as follows:

Based on the fact that the distinction between free choice items and affective polarity items is indeed lexicalized cross-linguistically, one can of course still argue that there are two indefinite anys, one free choice and one affective polarity item. This option is not excluded by the analysis offered here, but whether to adopt it or not seems to have been reduced to a relatively harmless, and perhaps even trivial, terminological issue.

Figure 2. One any vs. two any’s: the last 20 years

The list of Figure 2 is again not exhaustive. Because the period that is surveyed is less long in Figure 2 than in Figure 1, Figure 2 lists fewer studies. The low number also suggests that fewer people felt inspired to enter the debate, perhaps because they felt that they can only repeat what has been said already. Like Figure 1, Figure 2 also suggests that the majority view is that any is unambiguous. Of course, just because the univocal view is the majority view, this does not mean that it is correct. But there is a test which one can use independently of one’s view of what the univocal any actually involves. To quote Zwarts (1995, 294):

One of the strongest arguments for treating any as a single lexical item is the fact that it can always be modified by whatsoever and at all, while every and some cannot [...]

(9) repeats the Vendler examples shown in (1), so the Q∀ examples in a–c and the Q∃ examples in d–f, but with an additional whosoever or whatsoever.9

(9) a. Any doctor doctor whosoever will tell you what to do.

b. I can beat any whosoever of you.

c. Anybody whosoever who is my friend smokes a pipe.

d. Did you take any whatsoever?

e. If you ask any doctor whosoever, he will tell you …

f. I didn’t see any pigs whatsoever in the pen.

The observation was already expressed in Horn (1972, 161) and used as an argument for a univocal view, and a similar observation intrigued Seuren (1969, 123), who nevertheless remained uncommitted.

For it is a remarkable fact that in practically all cases of its occurrence any can be replaced by ‘no matter who/which/what/how much’ [...] One might, therefore, be inclined to reckon with one single any.

Should there really be only one any, what then is the nature of this any? And also, how do we explain that it has these two seemingly very different, uses, the Q∀ and the Q∃ one? Put in different and more concrete terms, what is this one meaning like, showing up in the any of both (10)a and (10)b and in both (11)a and (11)b, and why is the any in the a-sentences somewhat close – not identical – to every, and somewhat close – not identical – to some or a in the b-sentences?

(10) a. Anybody/everybody could see that.

b. Did you hear anybody/somebody?

(11) a. Any/every participant could see that.

b. Did you hear any/a voice?

4 Three types of univocal accounts

On the assumption that any really isn’t the same as every or some/a, all univocal any accounts take any to have a meaning sui generis, and the same is ‘quasi true’ for the quasi-univocal ones. There are three sui generis variants – and the third one comes in subvariants. A lot has been written about these accounts: I will suffice with a brief critical discussion of some representatives of each account.

The first variant takes any to be a universal quantifier sui generis, in particular, a universal quantifier with wide scope, different from the ‘normal’ universal quantifier, which has narrow scope. Quine (1960, 139–140) explains it as follows.

(12) a. I do not know any poem.

b. I do not know every poem.

In (12) a the universal quantifier takes wide scope, allowing the paraphrase (Quine’s paraphrase) ‘Given each poem in turn, I do not to know it.’ (12)b, however, denies that ‘given each poem in turn, I know it’. Interestingly, Quine does not pay attention to Q∀ uses and the example in (12)a is nowadays generally considered to be a Q∃ use.

Given that any is close to some, it is not surprising that there are also claims that any is always an existential quantifier sui generis. A clear statement can be found in Davison (1980, 16) and in Huddleston & Pullum (2002, 383). Here is what Davison (1980, 16) writes:

This position does not draw a semantic distinction between [the Q∃ and the Q∀] uses but it assigns any to the existential quantifier.

Now we come to the third approach: any is always a word sui generis or, to be innocently more specific, an ‘indefinite’ word sui generis, but not a universal or an existential quantifier. The 1962 Vendler analysis says exactly that: any is a free choice expression. Similar notions are ‘indifference’ (Jespersen 1933, 181), ‘whateverness’ (Bolinger 1960, 383)10, ‘arbitrariness’ (Tovena & Jayez 1999), ‘quodlibet’ (Hamilton 1858; Horn 2000b, 162), ‘indiscriminacy’ (Horn 2000a, 90; 2005, 185) and ‘undifferentiated choice’ (Farkas 2005). In Table 1 below I treat all these notions under ‘free choice’. I also put Dayal (1998) in this category. She expresses the common core, already alluded to before, as follows (Dayal 1998, 473).

[…] an any statement, whether it involves the universal or the indefinite variant, must be a property-loaded statement that applies to the whole class, not to particular members of that class.

This applies uncontroversially to the Q∀ use: one can freely choose among the participants in (11)a: the statement applies to all members of the class. Here is a passage that shows how she finds all members of the class for the Q∃ use:

[…] John didn’t see ∃-anything entails for all things that John didn’t see them. This essentially makes it a general statement, akin to statement with ∀-any.

In Vendler parlance, you may choose freely among the contextually relevant things and for the whole class it is true that John didn’t see them.

The free choice idea fits the whatsoever facts alluded to with (9) ; what else can whatsoever mean than that the choice is free. Note also that any does not collocate well with must.11

(13) *She must buy any dress.

When she must buy any dress, there is no free choice. Yet, merely saying that any expresses free choice is not enough. For one thing, why is (14) ungrammatical?

(14) *She wants to marry any Norwegian.

Surely, it does not matter which Norwegian is the lucky one: they are all fine future husbands.12

Table 1 shows four notions in addition to ‘free choice’, viz. scalarity, emphasis, veridicality and veridicality bleaching. I interpret the use of the notion of concessivity (from Lee 1996) as embodying the same idea as scalarity and I take widening (from Kadmon & Landman 1993) to be the same as emphasis. The table shows two things: (i) free choice is not the only notion characterizing the third sui generis account, and (ii) free choice can be combined with some of these other notions.

|

free choice |

scalarity |

emphasis |

non-veridicality |

veridicality bleaching |

|

|

Bolinger 1960; Vendler 1962; Dayal 1998; Farkas 2005 |

✓ |

||||

|

Lee 1996, Haspelmath 1997; Israel 2011 |

✓ |

||||

|

Kadmon & Landman 1993; Langacker 2003; Chierchia 2006 |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Zwarts 1995, 293–295 |

✓ |

||||

|

Tovena & Jayez 1999; Horn 2005, 182 |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Giannakidou 1998 |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 1. (Quasi-)univocal accounts

The importance of scalarity was first argued for by Fauconnier (1975) – later also Fauconnier (1979) – but he didn’t go as far as to use scalarity for a univocal or quasi-univocal view. Some of his followers did and Haspelmath (1997) is one of them. Haspelmath (1997, 117) argues the case with example (15) .

(15) If she can solve any problem, she’ll get a prize.

The Q∃ and Q∀ uses are paraphrased in (16) and Haspelmath claims that these sentences are equivalent to the ones in the ones in (17), which contain ‘quantifier superlatives’.

(16) a. If there is a problem she can solve, she’ll get a prize.

b. If she can solve every problem, she’ll get a prize.

(17) a. If she can solve the least difficult problem, she’ll get a prize.

b. If she can solve the most difficult problem, she’ll get a prize.

So in both (17) a and (17) b any refers to an end-value on a difficulty scale. In the Q∃ use the reference is to the least difficult problem and in the Q∀ use the reference is to the most difficult one.

It is not to be denied that any resembles quantifier superlatives, but claiming that the sentences with any and the ones with the quantifier superlatives are ‘equivalent’ is a different matter.13 Even if we accepted their equivalence and the implication that this shows that any is scalar in (15) , it would not follow that any any is scalar. (18) and (19) are variants of examples offered by Duffley & Larrivee (2010, 7), which they persuasively consider to be non-scalar (see also Rullmann 1996, 345; Larrivée 2007, 99; Muller 2007, 85; 2019, 196; Chung 2010, 266; Hoeksema 2010a, 189; Sohng 2014, 145).

(18) If you find any typos in this text, please let us know. [Q∃]

(19) Any key will reactivate the screen. [Q∀]

There are no scales on which the Q∃ typos of (18) and the Q∀ keys of (19) appear in an end position. For (18) all typos need to be found, bad ones, insulting ones, silly ones – it does not matter. Similarly for the keys of (19) : keys on the left or on the right will reactivate the screen, bigger keys (like the return key) too, numerical keys – it does not matter. And a few pages after the discussion of examples (16) and (17) Haspelmath (1997, 120) allows any to be used without a scalar endpoint, as in the imperative in (20) .

(20) Type any key. [Q∃]

I conclude that as a general account of any, a scalar account will not do. This critique also holds for accounts that posit scalarity for only the Q∃ use (e.g. Krifka 1990, 1994).

The emphasis analysis is represented by Kadmon & Landman (1993). They compare any to an indefinite article (both singular a(n) and the mass or plural zero article), both in Q∀ and Q∃ uses.

(21) a. An owl hunts mice.

b. Any owl hunts mice.

(22) a. I don’t have potatoes.

b. I don’t have any potatoes.

I will now convey the Kadmon & Landman idea in my own words, and these own words include the phrase ‘free choice’ in the Vendler sense. Kadmon & Landman have this phrase at their disposal, too, but only in the Ladusaw sense.14 The idea is the following: even though (21) a and (22) a do not contain any, the sentences express free choice already. To a fair extent, it does not matter which owl or which potatoes one would envisage to check whether an owl hunts mice or whether the speaker has potatoes. When one adds any, however, one emphasizes the choice element or, in Kadmon & Landman’s terminology, one ‘widens’ ‘the domain of quantification’ or, in the negative case in (22) b, one reduces it. Thus any versions are stronger and, in the words of the authors, widening goes hand in hand with ‘strengthening’. Dependent on the context, the speaker may have in mind that even old owls hunt mice, or sick ones, or old sick ones. Just how wide the domain the speaker has in mind is is left vague. And the speaker can make his statement even stronger.

(21) c. Any owl whatsoever hunts mice.

The same widening is expressed by any in the potatoes example of (22) b. With any the speaker may have in mind that he does not even have rotten potatoes or hard ones or hard rotten ones. And (22) c–d show that there can more be emphasis, i.e., more widening.

(22) c. I don’t have any potatoes whatsoever.

d. I don’t have any potatoes at all.

Two more points about the indefinite article are in order. First, I have stated that the indefinite articles of (21) a and (22) a convey free choice. This free choice, however, is context-dependent. The indefinite article in (23) , for instance, does not convey free choice.

(23) You met a man. I know him. Do you want to know his name?

Second, an indefinite article does not combine with whatsoever.

(24) a. *An owl whatsoever hunts mice.

b. *I don’t have potatoes whatsoever.

One could this take to imply that an indefinite article cannot, after all, express free choice and that there can therefore be no widening. However, the ‘articled’ owl and potatoes can be widened too, but not in the same way.

(25) a. An owl always hunts mice.

b. I don’t have potatoes at all.

c. I didn’t see a single owl.

So the counterargument fails.

The widening idea is close to the scalarity idea.15 In the paper in which Kadmon and Landman (1990) introduce widening, there is no reference to the work of Fauconnier or any other defender of the scalarity idea, and in the 1993 study the reference is indirect (Kadmon & Landman 1993, 371), in that they discuss the scalar approach of Krifka’s (1990, 282), which acknowledges a close relation of Fauconnier. It is certainly correct to say that ‘old owls’ are higher on some scale than ‘owls’ – or lower on the reverse scale – and that ‘rotten potatoes’ are higher/lower on some scale than ‘potatoes’. But there are at least two important differences between the widening and the scalarity approaches. First, the scalar approach crucially refers to just one scale: in (15) the scale is that of the difficulty of the problem. The widening account does not require there to be just one scale. The widened owl of (21) b may be old and thus higher/lower on an age scale, but a sick owl is just as widened and it is placed on a health scale instead of an age scale. So there can be multiple scales and they may even merge, as with a sick old owl. Second, the widening approach does not require the widened alternative to be positioned at the end of a scale.

Is the widening approach correct? Or, in a general jargon, is the use of any always emphatic? I think, in agreement with Krifka (1994, 195–196), Jackson (1995, 133), Rullmann (1996, 349), Rohrbaugh (1997, 312–313), Chierchia (2006, 559; 2013, 360), Jayez & Tovena (2010, 63), Israel (2011, 177) and Giannakidou (2011, 1687–1694)16, that widening is not necessary, at least not in unstressed Q∃ uses, such as that of (22) b. The Q∀ any in (21)b is widened, but the Q∃ one in (22) b is only widenable. The widening can take the form of stress, the addition of whatsoever or at all, or by both.

(26) I don’t have any potatoes. [no widening]

I don’t have ANY potatoes. I don’t have any potatoes whatsoever/at all. [widening]

I don’t have ANY potatoes whatsoever/at all. [more widening]

The widenability idea is similar to Chierchia’s (2006) version of the domain widening idea. For him “[d]omain widening […] is a potential for domain widening” (Chierchia 2006, 559). But there is a difference as well. For me there is no widening in I don’t have any potatoes; for Chierchia widening (taken to be an even implicature in the case of the Q∃ use, Chierchia 2006, 562) is still there, but only as “a formal requirement”, whatever the status of this “formal requirement” may be.

The third type of sui generis of any seems a little different. It does not aim to characterize any as such but rather the contexts or constructions in which it appears.17 The key concept is (non)veridicality. This notion is a simple:

[…] a linguistic item L is veridical if it expresses certainty about, or commitment to, the truth of a sentence, and L is nonveridical if it doesn’t express commitment. (Giannakidou 2011, 1675; also Giannakidou & Yoon 2014, 82)

An example of a nonveridical operator is clausal negation. Adding clausal negation to I saw an owl no longer commits the speaker to the truth of I saw an owl.

(27) I did not see an owl. ⊅ I saw an owl.

In an early paper Zwarts (1995, 204) phrases a hunch that “[w]hat these expressions [i.e., ‘free-choice any and polarity sensitive any’] appear to have in common is that they are restricted to nonveridical contexts”. Thus clausal negation accepts any.

(28) I did not see any owl.

There are two problems with this conjecture. First, there are veridical contexts allowing any.

(29) Lucy regrets that she talked to Jenny. ⊃ Lucy talked to Jenny.

(30) Lucy regrets that she talked to anybody.

Giannakidou, who took over from Zwarts in arguing for the relevance of the notion of (non)veridicality, has done a lot for solving this problem. Similar to Linebarger (1981), Giannakidou (2001, 722) initially associated the regret verb with a negative implicature. She later (2006, 596) was not sure anymore about the notion of implicature18 but still kept the idea that regret contains some negative semantic component or, at least, regret allows an inference, something like ‘Lucy didn’t want to talk to anybody’ for (29) , which then ‘rescues’ any. We see a similar problem – and solution – for the fact that any does not mind only, with only being veridical, yet associated with a non-veridical nobody other than semantic component, which ‘bleaches’ the veridicality (Giannakidou 2006, 595).

(31) Only Mary said something. ⊃ Mary said something.

(32) Only Mary said anything.

I suppose a similar solution would work for negated counterfactuals, which are also veridical.

(33) a. Mary should not have said anything.

b. If Mary had not said anything … ⊃ Mary has said something.

c. If only Mary had not said anything.

A third type of context with an associated non-veridical element ‘rescuing’ any are conditional postmodifiers discussed under the label ‘subtrigging’, since LeGrand (1975). Thus (34) has an ungrammatical any because the sentence is veridical. A relative clause, however, makes the sentence grammatical.

(34) *She bought anything at Carson’s.

(35) She bought anything she needed at Carson’s.

The explanation is that the relative construction has a conditional meaning. A protasis is non-veridical and it thus saves any (Giannakidou 2001, 717–722).

(36) If she needed anything, she bought it at Carson’s.

But note that though the anything in (35) is conditional, (35) and (36) are not equivalent: (35) is a ∀ construction, (36) is a Q∃ construction.

(37) She bought anything she needed at Carson’s.

≈ She bought everything she needed at Carson’s.

(38) If she needed anything, she bought it at Carson’s.

≈ If she needed something, she bought it at Carson’s.

Because of the conditional meaning, I will let go of the term ‘subtrigging’. I will also let go of the traditional term ‘conditional relative’ – traditional in studies on Classical Greek (e.g. Goodwin 1892, 305; Chase & Phillips 1966. 78; Bornemann 1973, 301).19 Instead I will use ‘conditional postmodifier’, in the spirit of Dayal (2004, 9), and the reason for preferring this to ‘conditional relative’ is that ‘conditional postmodifier’ includes conditional relatives, but is not limited to them, as illustrated in (39) .

(39) a. Anybody friendly to me smokes a pipe.

b. Anybody who is friendly to me smokes a pipe.

The conditional postmodification also applies to the uses in (40) and (41).

(40) After dinner, we threw away any leftovers.

(41) Mary confidently answered any objections.

For Dayal (2004, 9) and Israel (2001, 188) these constructions show conditional postmodification with a covert or pragmatic postmodifier. My view is a little different. Note that (40) and (41) both contain nominalizations: leftovers means ‘things that were left over’ and objections means ‘things that were objected to’ and I propose to see these as providing the postmodifiers. In this view, the postmodifiers are not really covert, but only hidden.

There are also uses of a veridical any for which no associated non-veridical element rescuing any would seem to help.

(42) So I just said anything to fill the silence.

(43) It was anybody’s guess.

(44) There are any number of studies by independent investigators.

(45) Anybody who was anybody came out of the school of Art Blakey.

(42), discussed by Vlachou (2007, 69), has the just typical for what Horn (2000b) has called the ‘anti-indiscriminative’ use (not just anything), except that there is no negation. It is very rare.20 The type of pattern in (43) is rare, maybe it only occurs with guess, game and business, but the token frequency is not. (44) has the ‘many’ use of any, Stoffel’s (1899) ‘intensive use’ (building on Fijn Van Draat 1897), recognized by Jespersen (1949, 603). The second any in (45) is Haspelmath’s (1997, 188) ‘appreciative’ any (building on Stoffel 1899). What unites these uses is that they are veridical and there is no implicated or associated non-veridical meaning bleaching the veridicality. I will come back to these constructions in section 4, but for now what matters is only that these constructions are veridical, there is no associated non-veridical component, and yet these constructions combine with any.

Then there is a second problem: neither Zwarts’ hypothesis nor Giannakidou’s are specific enough: they do not say that all nonveridical contexts accept any, and this is indeed not the case. The verb want is nonveridical, yet, as already illustrated in (14), it doesn’t always accept any.

(46) She wants to marry a Norwegian. ⊅ She marries a Norwegian.

(14) *She wants to marry any Norwegian.

Giannakidou (2001) is aware of the problem and reflects it by a parlance of a veridical context not licencing any (called ‘antilicencing’ ) instead of one of non-veridical contexts licencing any. This does not tell us why some non-veridical contexts do licence any.

This does not exhaust the discussion. And, of course, there is the next question. How do univocal accounts distinguish between the Q∃ and Q∀ uses? In some of the accounts, such as Bolinger (1960) or Vendler (1962) this question is not addressed. Some do address the question. In what follows I will briefly discuss just two of the classical ones.

For Davison any is an existential quantifier. Thus she has no problem accounting for the Q∃ use. The Q∀ use takes the existential quantifier and adds a conversational implicature. The details are not spelled out, however. And I see one fundamental problem: a conversational implicature has to be cancellable. Some, for instance, is traditionally taken to conversationally implicate ‘not all’ and this implicature is indeed cancellable, as is shown in (47) .

(47) I have read some books and, in fact, I have read all of them.

Thus the alleged ‘all’ implicature added to the literal existential meaning of any should be cancellable, too. But, as (48) shows, the alleged implicature is not cancellable.

(48) *I can hear anything, and, in fact, I cannot hear everything.

This makes the Davison account – and similar ones (Giannakidou 2001, 725; Huddleston & Pullum 2002, 383) implausible.

Genericity is appealed to both in the widening approach of Kadmon & Landman’s (1993) and the scalarity approach of Horn’s (2000a, 2000b). The Q∀ uses are claimed to be generic and the Q∃ non-generic. The idea is plausible for the owl cases. But it can’t be true for a modal non-generic case such (1)b (see also Sohng 2014, 141).

(1) b. I can beat any of you.

Kadmon & Landman (1993, 406) are aware of the problem and leave it for a later paper …. which, apparently, did not materialize.

5 Another sui generis free choice account

In the preceding pages I have shown that in current scholarship the sui generis account takes pride of place, that there are at least three variants and that they are problems. In this section, I will offer another variant. Three properties of the new account are crucial.

First, I claim that the meaning of any has two components. viz. free choice and existence. Claiming that any expresses free choice is not, of course, new. Table 1 catalogued various accounts in which any has free choice as the core meaning or part of the core meaning. In the latter case free choice combined with at least one other component, viz. scalarity, emphasis, veridicality or veridicality bleaching. In the ‘new’ account there is also another component, viz. existence. Existence is not unknown either, but in this case it is posited as one of two components.

Second, I treat the status of the two components in terms of what is or is not ‘at issue’ or what is or not ‘assertorically active’. ‘At-issueness’ is not a new concept either. It has been gaining prominence in the work on the semantics pragmatics interface, partially building on and replacing earlier work on presupposition and implicature (Horn 2002; Tonhauser 2012; Horn 2016; Koev 2018; compare also Klein & von Stutterheim 1987; Roberts 1996). The idea is simple: the component that is not at issue is taken to be true and it is backgrounded or presupposed. The component that is at issue or assertorically active is either asserted or not asserted, in which case the speaker may deny it or remain uncommitted. Consider the sentences in (49) .

(49) a. Only John attended the meeting.

b. Not only John attended the meeting.

c. Did only John attend the meeting?

d. If only John attended the meeting, that is not too good.

The semantics of only has two components, represented for (49) in (50) .

(50) a. John attended the meeting.

b. Nobody other than John attended the meeting.

In none of the four sentences in (49) is the a-component at issue. The b-component is at issue, and in (49) a it is asserted, in (49) b–d it is not asserted, either denied, as in (49) b, or, as in (49) c–d, seen as something that the speaker does not commit too. I find work on elements with two semantic components, such as Horn (2002) and Gast (2013), on which the brief discussion of only is based, particularly convincing. It is my hope that work on any, which I also take to involve two semantic components, is convincing too.

The third feature of the new account is the claim that it is not enough to describe the core meaning of any, i.e., the meaning that is present in all its uses. The ‘use’ aspect, the contexts or constructions is which any occurs is, also part of the meaning. I have no objection to a jargon of ‘uses’, ‘functions’, ‘contexts’ ‘constructions’ or ‘meanings-in-context’ or to there being a ‘licencing question’ in the analysis of the interaction of the core meaning and the context, but I insist on the claim that this matter also characterizes the meaning of any. The term I use is ‘constructional meaning’ (cp. Langacker 2003, 291; Hoeksema 2010a, 218). I argue for this view with the semantic map approach, heralded for any by Haspelmath (1997) (see also section 5.6). The Haspelmath map has cells, and since the map is a semantic map, the cells represent semantic entities (van der Auwera & Temürcü 2006; Gast & van der Auwera 2013, 132;21 Forker 2016, 86).

So much for three crucial properties of the ensuing account. It is important to stress that the account also lacks some properties. Thus it does not posit scalarity, widening or non-veridicality as inherent properties. They are interesting properties, but they are not definitional. It is no less important to mention an important restriction: except for some remarks in section 5.5, I only discuss non-stressed any.

In the constructional meaning the core meaning interacts with the context. The core meaning has two components, viz. free choice and existence. In the interaction with the context, each component may or may not be at issue. There are four possibilities: just one component is at issue, either free choice or existence, both are at issue and neither are at issue. When a component is at issue, the speaker can assert it, negate it or remain uncommitted. The resulting meaning can be Q∀ or Q∃. So there are rather many logically possible constellations. In what follows I will discuss the constellations that are attested.

5.1 Existence at issue

The claim on the core meaning is simple: any expresses both existence and free choice. The claim that any implies existence would not be appreciated by Vendler (1962). He uses the phrase ‘existential import’ (1962, 156) and he denies it for any. In particular, he denies it for sentences like (51) a and b. (Vendler 1962, 158) and he would have done it for (51) c, too.

(51) a. Did you any pigs in the pen?

b. I didn’t see any pigs in the pen.

c. If you see any pigs in the pen, let me know.

Any, he claims, is existentially neutral. I disagree. It is, of course, true that the sentences in (51) do not have existential import. In (51) a, existence is questioned, in (51) b existence is denied and in the conditional in (51)c existence is uncertain, but that is because of the negative, interrogative and conditional structure. Note that these contexts do not negate, question or ‘conditionalize’ the free choice component: this element is ‘not at issue’. (51) allows the hearer to freely choose anything in the pen to check whether it is a pig. (51)b similarly reports that there has been freedom of choice of the things of the pen with respect to whether these things are pigs.22 And the conditional does not target the free choice element either: the hearer can investigate anything in the pen to see whether there are (‘exist’) pigs among them.

|

constructional meaning |

construction |

|||

|

not at issue |

at issue |

asserted, negated or not committed |

Q∃ or Q∀ |

|

|

free choice |

existence |

negated |

Q∃ |

I didn’t see any pigs in the pen. |

|

not committed |

Q∃ |

Did you see any pigs in the pen? If you see any pigs in the pen, let me know. |

||

Table 2. any: existence at issue

5.2 Existence and free choice at issue

The conditional postmodifier use was already discussed in Vendler (1962, 156) and, like for the ‘pig’ uses Vendler denies this any to have existential import.

(1) c. Anybody who is my friend smokes a pipe.

Since (1)c has a conditional meaning, the analysis is similar to that of (51)c. So existence is at issue and it is conditionalized. But, as illustrated in (37) and (38) , (1)c has a Q∀ reading, unlike (51)c. I propose to reflect this by claiming that free choice is at issue too. This is not to say that when existence and free choice are both at issue, the result has to be Q∀ reading. In particular, in the rare case of (52) it seems to me that both components are at issue, but the result is undeniably a Q∃ reading.

(52) So I just said anything to fill the silence.

≈ So I just said something to fill the silence.

The ‘intensive’ any in (53) is similar, except that the Q∃ reading has an additional component: it is not just that there are these studies, free to choose from, but there are many of them.

(53) There are any studies by independent investigators.

≈ There are many studies by independent investigators.

If it does not matter who undertook these studies, it invites the implicature that they are many. It makes sense to see the intensive use as a conventionalization of this implicature.

|

constructional meaning |

construction |

|||

|

not at issue |

at issue |

asserted, negated or not committed |

Q∃ or Q∀ |

|

|

– |

existence |

not committed |

Q∀ |

Anybody who is my friend smokes a pipe. |

|

free choice |

asserted |

|||

|

existence |

asserted |

Q∃ |

So I just said anything to fill the silence. |

|

|

free choice |

asserted |

|||

|

existence |

asserted |

Q∃ ‘many’ |

There are any studies by independent investigators. |

|

|

free choice |

asserted |

|||

Table 3. any: existence and free choice at issue

5.3 Free choice at issue

A first such use, already discussed by Vendler (1962), is the classical Q∀ use, of (1)b, repeated below.

(1) b. I can beat any of you.

In this Q∀ use, only the free choice component is at issue. It is taken for granted that there are beatable addressees, who exist in the different scenarios (‘possible worlds’, if you like) conveyed by the possibility operator. The Q∀ sense is not only due to any, but to the combination of the possibility modal and the free choice components of any.

Another classical Q∀ use, not discussed by Vendler, is the generic one.

(21) b. Any owl eats mice.

What is at issue is the extent of the ‘domain of quantification’. It is taken for granted that there are owls that hunt mice, it is now asserted that one can choose any owl, even marginal exemplars, like old or sick ones, and find out that they eat mice. The same analysis holds for (43), repeated in (54) with its Q∀ paraphrase.

(54) It was anybody’s guess.

≈ It was everybody’s guess.

In (54) the existence of people that had ideas about ‘it’ is not at issue. With anybody’s guess it does not matter whose opinion we check – even people that are otherwise most knowledgeable with respect to what was discussed didn’t know.

Other uses not mentioned by Vendler (1962) but widely discussed later, are the comparative and imperative ones. For both the status has been controversial. Are they Q∀ or Q∃ uses or, in the Ladusaw tradition, are they ‘negative polarity’ or ‘free choice’ uses? (55) illustrates the comparative, both its phrasal and its clausal version.

(55) a. You know your business better than anyone.

b. You know your business better than anyone had expected.

The two types differ in interesting respects (Hoeksema 1983; also Giannakidou & Yoon 2014), but they are both Q∀ uses.

(56) a. You know your business better than everyone.

b. You know your business better than everyone had expected.

What is special is that the ‘quasiness’ of the phrasal type is a bit stronger. As pointed out by Hoeksema (2010a, 852–853), the standard of the phrasal comparison of an any constituent does not include the comparee. In the case of (55) a the standard of comparison is not supposed to include the addressee: the addressee really does not know his/her business better than the addressee himself/herself. So anyone here is to be pragmatically enriched to anyone else, and the same goes for the phrasal comparative with everyone.

(57) You know your business better than everyone.

(58) a. You know your business better than anyone else.

b. You know your business better than everyone else.

This is different for the clausal type: it is possible that the addressee hadn’t himself/herself expected to know his/her business that well either. In any case, in (55) a there are people other than the addressee and in the comparison with the addressee one can freely choose all of them and find out that they do not know their business (or that of the addressee) as well as the addressee. The existence of people that know their business is not at issue, it is the free choice element that is at issue and asserted. Similarly for (55) b: it is not at issue that there are people that had expected his/or her business not to go so well, but rather that one can freely choose anyone and find out that they had this negative expectation.23

As to the imperative use in (20), repeated in (59), it is clear that the addressee is not supposed to type all keys.

(59) Turn any key.

≈ Turn some key.

≠ Turn every key.

So we are dealing with a Q∃ use and what is at issue is free choice, not existence.24 The imperative (59) is subtly different from the modal case, shown in (60) .

(60) You may turn any key.

≈ You may turn every key.

≠ You may turn some key.

(60) has a Q∀ reading, which is due to the possibility operator, conveying a plurality of situations.

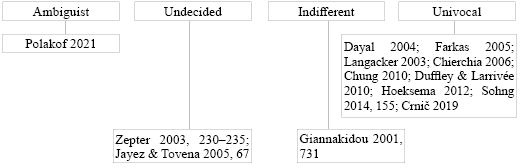

In all the uses discussed so far, the free choice meaning was asserted. But it can also be be negated. This is what Horn (2000a, 90; 2000b, 173) has called the ‘anti-indiscriminative’ uses of any and Haspelmath (1997, 190–192) ‘anti-depreciative’. I take Horn’s ‘indiscrimination’ to be the same as ‘free choice’, so ‘anti-indiscriminative’ is an adjective referring to uses that lack the free choice component. There are three strategies that can have this effect – and they can be combined too. A first strategy is the use of the particle just and a second one uses the adjective old (if any accompanies a noun). In order to be able to show the effect of old, I will use an example with a noun. Just and old can be combined.

(61) a. I didn’t drink just any Chardonnay.

b. I didn’t drink any old Chardonnay.

c. I didn’t drink just any old Chardonnay.

What is at issue is the free choice component, it is negated, and the reading is a Q∃ one, in the sense that both on an episodic and a habitual reading the subject drank one or a few Chardonnay’s but not all.

Horn (2000b, 150) studied the particle just. He showed that it has various uses and that what it expresses in a context like (62) a is the exclusion of an alternative that is higher on a qualitative scale. In a negative context, the exclusion is denied, so we end up with the inclusion of a higher value.

(62) a. He is just a sergeant, not a general.

b. He is not just a sergeant, he is a general.

Consider (61)a now. What qualitative scalar meaning is there in the any constituent that can be denied. It is not existence. Free choice, on the other hand, is eminently scalar: a choice can be more or less free. So what not just does in (61) a is to deny free choice or better to deny the fullness of the free choice. It allows the other extreme, but that is not necessary, a point on which I disagree with Horn (1972, 149; 2000b, 171, 177) and with Israel (2011, 175). Figure 3 sketches a choice scale and exemplifies the increasing specificness on a Chardonnay scale.

Figure 3. A Chardonnay scale

The function of old might not have been studied yet. But the basic picture is clear: old is seen as a low value, the low value is a low degree of the specificness of the choice, this is denied, so we end up with a more specific choice. As to existence, it is not at issue.

The shrinking of free choice with a not any can also be reached by intonation, either by itself or in combination with just and/or old. Already Palmer (1929, 11) made the relevant observation, as dutifully referred to by Jespersen (1949, 606). (63) was their example.

(63) I don’t lend my books to anybody.

a. ‘I lend my books to nobody.’

b. ‘I am very peculiar as to whom I lend my books.’

Jespersen (1949, 606) associated the first reading with high-falling tone on anybody and the second one with a rise-fall-rise, nowadays called ‘fall-rise’. Haspelmath (1997, 191) made the same point and Bolinger (1960, 379), followed by Horn (2000b, 176), added the nuance that the fall-rise prosody is typical for the b reading but that it is not really required.

How does fall-rise intonation yield the specificness reading? Here is an example of Ladd’s (1978, 154) – ‘ˇ’ marks the fall-rise intonation.

(64) A: You have a VW, don’t you?

B: I’ve got an ˇOpel.

What B does is to focus on the Opel as a member of a set, like the set of German cars, and convey that the Opel is not quite good enough25 as a member of that set, for A asked about a VW. So there is an element of exclusion of the better value. With a negation, the better value will be included, with any the values are degrees of specificness and with a negation it is the higher degree of specificness that is included.

We also find the specific reading in negative sentences that have any with a predicate nominal, with either just and/or old and/or fall-rise intonation.

(65) a. A salmon is not just any fish.

b. A salmon is not any old fish.

c. A salmon is not ˇany fish.

On the scale of specific fish, any here conveys a higher value. This is not to say the predicate nominal use of any only have this specificness reading. Consider (66), due to Horn (2005, 199).

(66) Robin is not any friend of mine.

‘Robin is not a member of my set of friends.’

‘Robin is a specific friend.’

Finally, there is also the ‘appreciative’ use of (67) . It is similar to the Chardonnay and the fish cases except that free choice is not negated but ‘conditionalized’.

(67) Anybody who was anybody came out of the school of Art Blakey.

≈ Anybody who was somebody came out of the school of Art Blakey.

Table 4 summarizes the discussion.

|

constructional meaning |

construction |

|||

|

not at issue |

at issue |

asserted, negated or not committed |

Q∃ or Q∀ |

|

|

existence |

free choice |

asserted |

Q∀ |

I can beat any of you. Any owl eats mice. It was anybody’s guess. You know your business better than anybody (had expected). |

|

Q∃ |

Turn on any key, |

|||

|

negated |

Q∃ |

I don’t drink just any Chardonnay. I don’t drink any old Chardonnay. I don’t drink ˇany Chardonnay. |

||

|

uncommitted |

Q∃ |

Anybody who was anybody came out of the school of Art Blakey, |

||

Table 4. Any: free choice at issue

5.4 Neither existence nor free choice at issue

I now turn to three uses in which any has neither free choice nor existence at issue. In each case it is not only the meaning of any that has two components, but the any eliciting/rescuing operators have two as well. With the only … any sentence in (32) the issue is whether there are more people than Mary that said something, and it is asserted that this is not the case.

(32) Only Mary said anything.

This asserted negativity of only aligns it with the asserted negativity of the clausal negation in (51)b, and in both it triggers any. But in (32) neither of the two components of any is at issue: Mary said something and it is not at issue what she said. All that matters is whether or not Mary was the only one to have said anything.

Emotive predicates and negated counterfactuals are similar.

(30) Lucy regrets that she talked to anybody.

(33) a. Mary should not have said anything.

b. If Mary had not said anything …

c. If only Mary had not said anything.

The emotive and negative counterfactual constructions also have two components. Thus regret expresses that what is regretted is a fact, but that it is ‘bad’. Similarly, a negated counterfactual expresses that the non-counterfactual state of affairs is a fact but a ‘bad’ one. In both cases it is the negative evaluation that is at issue, not the state of affairs regretted or ‘uncounterfactual’ nor the existence or the identity of the person Lucy talked to or the existence or the nature of what Mary said.

Table 5 is a summary.

|

constructional meaning |

construction |

|||

|

not at issue |

at issue |

asserted, negated or not committed |

Q∃ or Q∀ |

|

|

existence free choice |

– |

– |

Q∃ |

Only Mary said anything. Lucy regrets that she talked to anybody. Mary should not have said anything. |

Table 5. Any: neither existence nor free choice at issue

5.5 Other ‘issues’

In the discussion in section 5.1 to 5.4 I have attempted to describe and partially explain a fair amount of constructional meanings, in terms of a univocal analysis of a core meaning with two components, both of which may or may not be at issue. But much is left untouched.

For one thing, the context may have features that trigger more than one constructional meaning and at least in some cases, the construction will be ambiguous. This is the case with example (15) , repeated below.

(15) If she can solve any problem, she’ll get a prize.

In (15) the possibility modal triggers the Q∀ reading and the conditional context the Q∃ reading. The result is that (15) allows two readings. I will not investigate where and how ambiguities of this kind arise.

For another thing, I have only discussed non-stressed any. It is clear that a full account will also have to deal with the effect of stress. I will restrict myself to a few comments. First, in the constellation with only free choice at issue, it seems that stress will only emphasize – or ‘widen’ – the free choice, just like whatsoever or at all, as already argued around the examples in (26) .

(26) I don’ have any potatoes. [no widening]

I don’t have ANY potatoes. I don’t have any potatoes

whatsoever/at all. [widening]

I don’t have ANY potatoes whatsoever/at all. [more widening]

But what happens when one stresses any in any of the three other constellations. Consider (1)f again.

(1) f. I didn’t see any pigs in the pen.

In (1)f free choice is not at issue, all that is at issue of the existence of the pigs and it is asserted that there aren’t any, no matter how hard one searches. But what about (68) ?

(68) I didn’t see ANY pigs in the pen.

Stress, I propose, makes free choice an issue … but what is its effect on the existence component? I am inclined to think that existence remains at issue.

5.6 The relation between core meanings and constructional meanings

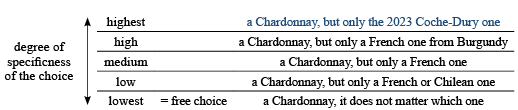

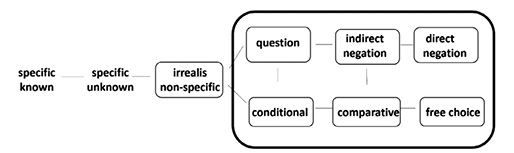

A good way to visualize the difference between core and constructional meanings is the semantic map method. Figure 4 shows Haspelmath’s indefiniteness map. The six small ovals are the six constructional meanings of any and the big oval is the core meaning.

Figure 4. The meanings of any (Haspelmath 1997, 65, 68, 249)

Though the general idea behind the map has stood the test of time, it is not descriptively adequate. Several constructional meanings already described by Haspelmath (1997) are not on the map, viz. the anti-discriminative and the appreciative any. We are now a quarter century later and there are various proposals to split up cells and to add cells (Kozhanov 2010; Aguilar-Guevara et al. 2011; Van Alsenoy 2014) (compare also the lists in Giannakidou 1998, 89; 2001, 677). And, of course, in this paper I have argued that ‘free choice’ should not be relegated to the one cell on the right-hand corner, it constitutes part of the core meaning. The point I want to make now is independent of the descriptive adequacy of the map in Figure 4 or of any successor maps. The point is this: elements that have the same core meaning do not have to share the same constructional meanings. The oldest examples of appreciative any and the any of anybody’s game pattern in the The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) are 1826 and 1840. Imagine now that these constructional meanings really didn’t occur before, say, 1825, but that all the other constructional meanings are the same as the ones we see today. In my view, both the any of 1825 and that of 2024 have the same core meaning but different, though overlapping constructional meanings.

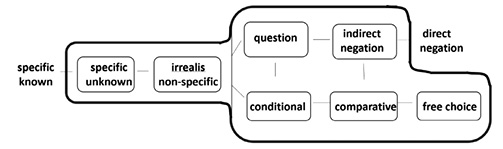

Note that an overlap of the constructional meanings going with the free choice core meaning of two indefinites does not imply that these indefinites have an identical core meaning. This point can be made concrete with a comparison between English any and German irgend. Figure 5 shows the core and constructional meanings of irgend in Haspelmath (1997, 245).

Figure 5. The meanings of irgend in Haspelmath (1997, 245)

It can be seen that the constructional meanings of any and irgend overlap. This is largely correct, but not completely. There has been quite some research about irgend since Haspelmath (1997) (Aguilar-Guevara et al. 2011; Aloni & Port 2014; Van Alsenoy 2014, 391–400), so the map is not fully correct. For one thing, Haspelmath’s ‘free choice’, which is Ladusaw’s ‘free choice’, has to distinguish between modal and generic meanings. Irgend allows the modal use, but not the generic one.

(69) Dieses Problem kann irgenjemand lösen.

this problem can anyone solve

‘Anyone can solve this problem.’

(70) *Irgendwelche Eule jagt Mäuse.

any owl hunts mice

‘Any owl hunts mice.’

But one detail that is correct in the Haspelmath map is that irgend has an ignorance reading, the ‘specific unknown’ reading in the terminology of Haspelmath (1997), while English any doesn’t have one. (71) is his irgend example (Haspelmath 1997, 245).

(71) Ich habe irgend etwas verloren, aber ich weiß nicht, was.

I have somewhere something lost but I know not what

‘I have lost something, but I don’t know what.’

The ignorance meaning is not a free choice meaning. What is it then, the indefiniteness that is common to ignorance and free choice and that characterizes irgend? It is not indefiniteness, for that term is too wide and ‘non-specificness’ won’t do either. ‘Indeterminacy’ is an option, But, do we really need a term for every possible range of contextual meanings found in languages? On the basis of just Haspelmath (1997, 76) there would be 37, for van der Auwera & Van Alsenoy (2011b, 339–343), there would be more than 50 and on the basis of what we know now the number would be higher still. Let’s be terminologically modest.

6 Conclusion

Since the word any has been subjected to semantic scrutiny for such a long time, perhaps I should provide some justification for yet another paper on the topic […] (Dayal 2004, 6)

Why did I devote ‘yet another paper’ to any? I hope to have shown that there is more than one justification. First, roughly twenty years after Horn (2000a, 2000b, 2005) took stock of the scholarship of any, it was time to do it again. I have included scholarship that appeared after Horn’s surveys, I have analysed the debate in a somewhat different way and I focused on rendering unto Vendler what is due to Vendler, viz. his view on ‘free choice’. However, it is important to stress that my survey cannot justice to the panoply of hypotheses and arguments. Second, despite the fact that so much has already been said about any, I hope to have come up with a somewhat different analysis. First, like a few other accounts, I take the meaning of any to have two components, one of which is free choice, but, unlike these accounts, I take the second component to be existence. Second, unlike some earlier work, I stressed that any does not only have a core meaning, but that the interaction between the core meaning and the context is part of the meaning too, not the core meaning, but what I called the ‘constructional meanings’. Third, I described the constructional meanings in terms of which of the components is or is not at issue.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented at the 58. Linguistisches Kolloquium in Vilnius (September 2023), and parts of it also elsewhere. I am thankful for the discussions. Special thanks are also due to Richard Smith (Warwick) and to the two reviewers.

List of abbreviaitons

Q∀ ‘quasi-universalist’

Q∃ ‘quasi-existentialist’

References

Aguilar-Guevara, Ana, Maria Aloni, Angelika Port, Radek Šimik, Machteld de Vos & Hedde Zeijlstra. 2011. Semantics and pragmatics of indefinites: Methodology for a synchronic and diachronic corpus study. Beyond semantics: Corpus-based investigations of pragmatic and discourse phenomena. Stefanie Dipper & Heike Zinsmeister, eds. Bochum: Bochumer Linguistische Arbeiten. 1–16.

Aloni, Maria & Angelika Port. 2014. Modal inferences in marked indefinites: the case of German irgend-indefinites. Weak referentiality. Ana Aguilar-Guevara, Bert Le Bruyn & Joost Zwarts, eds. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.219.02alo

Annear Thompson, Sandra. 1971. The structure of relative clauses. Studies in linguistic semantics. Charles J. Fillmore & D. Terence Langendoen, eds. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. 78–94.

Baker, C. J. 1970. Doubl‘ quasi-universalist’e negatives. Linguistic Inquiry 1, 169–186.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1960. Linguistic science and linguistic engineering. Word 16, 374–391.

Bornemann, Eduard. 1973. Griechische Grammatik. Frankfurt am Main: Moritz Diesterweg.

Carlson, Greg N. 1980. Polarity any is existential. Linguistic Inquiry 11, 799–804.

Carlson, Gregory. 1981. Distribution of Free-Choice any. Papers from the Seventeenth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Robert A. Hendrick, Carrie S. Masek & Mary Frances Miller, eds. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society. 8–23.

Chase, Alson Hurd & Henry Phillips, Jr. 1966. A new introduction to Greek. Third edition, revised and enlarged. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2006. Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the ‘logicality of meaning’. Linguistic Inquiry 37, 535–590. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2006.37.4.535

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2013. Logic in grammar. Polarity, free choice, and intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697977.001.0001

Chung, Younghan. 2010. The free choice condition for any, a free choice indefinite. Studies in British and American Language and Literature 3, 257–289.

Corblin, Francis, Lucia M. Tovena & Evangelia Vlachou. 2010. Le problématique des indéfinis de choix libre du français. Langue française 166, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3917/lf.166.0003

Crnič, Luka. 2019. Any: Logic, likelihood, and context (Pt.2). Language and Linguisitics Compass 13. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12353

Davison, Alice. 1980. Any as universal or existential. The semantics of determiners. Johan van der Auwera, ed. London & Baltimore: Croom Helm & University Park Press. 11–40.

Dayal, Vaneeta. 1995. Licensing any in non-negative non-modal contexts. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 5, 39–58. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v5i0.2694

Dayal, Vaneeta. 1998. Any as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy 21, 433–476. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005494000753

Dayal, Vaneeta. 2004. The universal force of free choice any. Linguistics Variation Yearbook 4, 5–40. https://doi.org/10.1075/livy.4.02day

De Morgan, Augustus. [1862] 1966. On the syllogism V. On the syllogism and other logical writings by Augustus De Morgan. Peter Heath, ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 208–246.

Duffley, Patrick & Pierre Larrivée. 2010. Anyone for non-scalarity? English Language and Linguistics 14, 1–17. 10.1017/S1360674309990402

Farkas, Donka F. 2005. Free choice in Romanian. Drawing the boundaries of meaning. Neo-Gricean studies in pragmatics and semantics in honour of Laurence R. Horn. Betty J. Birner & Gregory Ward, eds. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.80.06far

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1975. Pragmatic scales and logical structures. Linguistic Inquiry 6, 353–375.

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1979. Implication reversal in natural language. Formal semantics and pragmatics for natural languages. Franz Guenthner & Siegfried J. Schmidt, eds. Dordrecht: Reidel. 289–301.

Fijn van Draat, P[ieter]. 1897. A remarkable application of the word any. Englische Studien 24, 152–155.

Forker, Diana. 2016. Toward a typology for additive markers. Lingua 180, 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2016.03.008

Gajewski, Jon. 2022. On Ladusaw’s ‘On the notion Affective in the analysis of negative-polarity items’. A reader’s guide to classical papers in formal semantics. Louise McNally & Zoltán Gendler Szabó, eds. Cham: Springer. 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85308-2_15

Gast, Volker. 2013. At least, wenigstens, and company: Negated universal quantification and the typology of focus particles. Strategies of quantification. Kook-Hee Gil, Steve Harlow & George Tsoulas, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199692439.003.0006

Gast, Volker & Johan van der Auwera. 2013. Towards a distributional typology of human impersonal pronouns. Languages across boundaries: Studies in memory of Anna Siewierska. Dik Bakker & Martin Haspelmath, eds. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton. 119–158. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110331127.119

Geach, Peter Thomas. 1972. Reference and generality. An examination of some medieval and modern theories. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://www.degruyter.com/database/COGBIB/entry/cogbib.4429/html

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1999. Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy 22, 367–421. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005492130684

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2001. The meaning of free choice. Linguistics and Philosophy 24. 659–735. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012758115458

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2006. Only, emotive factive verbs, and the dual nature of polarity dependency. Language 82, 575–603. https://home.uchicago.edu/~giannaki/pubs/GiannaLanguage.pdf

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2011. Negative and positive polarity items. Semantics. An international handbook of natural languages meaning. Volume 2. Klaus von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn & Paul Portner, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. 1660–1712.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2018. A critical assessment of exhaustivity for negative polarity items. Acta Linguistica Academica 66, 503–546. https://doi.org/10.1556/2062.2018.65.4.1

Giannakidou, Anastasia & Suwon Yoon. 2014. No NPI licensing in comparatives. Proceedings of the Forty-sixth annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. The main session. Rebekah Baglini, Timothy Grinsell, Jonathan Keane, Adam Roth Singerman & Julia Thomas, eds. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. 79–96.

Goodwin, William W. 1892. A Greek grammar. Revised and enlarged. Boston: Ginn and Company.

Greenbaum, Sidney. 1996. English grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamilton, Sir William. 1858. Discussions on philosophy and literature. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Haspelmath, Martin. 1997. Indefinite pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, Jaakko. 1980. On the any-thesis and the methodology of linguistics. Linguistics and philosophy 4, 101–122.

Hoeksema, Jack. 1983. Negative polarity and the comparative. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1, 403–434.

Hoeksema, Jack. 2010a. Dutch ENIG: from veridicality to downward entailment. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28, 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-010-9110-4

Hoeksema, Jack. 2010b. Negative and positive polarity items: an investigation of the interplay of lexical meaning and global conditions of expressions. The expression of negation. Laurence R. Horn, ed. Berlin: Mouton. 187–224.

Hoeksema, Jack. 2012. Wie dan ook, wat dan ook, etc. als free choice indefinites en negatief-polaire uitdrukkingen. Tabu 40, 89–109.

Horn, Laurence R. 1972. On the semantic properties of logical operators in English. Doctoral dissertation, University of California at Los Angeles.

Horn, Laurence R. 2000a. Any and (-ever): Free choice and free relatives. The proceedings of the fifteenth annual conference. The Israel Association for Theoretical Linguistics. Adam Zachary Wyner. ed. 71–111. https://www.iatl.org.il/?page_id=27. Accessed 5 March 2024.

Horn, Laurence R. 2000b. Pick a theory (not just any theory). Indiscriminatives and the free-choice indefinite. Negation and polarity. Syntactic and semantic perspectives. Laurence R. Horn & Yasuhiko Kato, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 147–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198238744.003.0006

Horn, Laurence R. 2002. Assertoric inertia and NPI licensing. Papers from the panels of the thirty-eighth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Mary Andronis, Erin Debenport, Anne Pycha & Keiko Yochimura, eds. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. 55–82.

Horn, Laurence R. 2005. Airport ’86 revisited: Toward a unified indefinite any. Reference and quantification. The Partee effect. Gregory N. Carlson & Francis Jeffry Pelletier, eds. Stanford: Center for the study of language and information. 179–205.

Horn, Laurence R. 2016. Information structure and the landscape of (non-)at-issue meaning. The Oxford handbook of information structure. Caroline Féry & Shinichiro Ishihara, eds.Oxford: Oxford University Press. 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.009

Horn, Laurence & Young-Suk Lee. 1995. How many any’s? Diagnosing the diagnostics. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, New Orleans.

Huddleston, Rodney & Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316423530

Israel, Michael. 1996. Polarity sensitivity as lexical semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 19, 619–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00632710

Israel, Michael. 2004. The pragmatics of polarity. The handbook of pragmatics. Laurence R. Horn & Gregory Ward, eds. Oxford: Blackwel. 701–723.

Israel, Michael. 2011. The grammar of polarity. Pragmatics, sensitivity, and the logic of scales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511975288

Jackson, Eric. 1995. Negative polarity and general statements. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 5, 130–147.

Jayez, Jacques & Lucia M. Tovena. 2010. Quatre problèmes pour le choix libre. Language française 166, 51–72.

Jennings, Raymond Earl. 1994. The genealogy of disjunction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jespersen, Otto. 1897. Kortfattet Engelsk gammatik for tale og skriftsproget [A concise English grammar for spoken and written language]. 2nd edition. Copenhagen: Det Shubotheske Forlag.

Jespersen, Otto. 1933. Essentials of English grammar. London: Allen & Unwin.

Jespersen, Otto. 1949. A modern English grammar on historical principles. Part VII. Syntax. Copenhagen: Eijnar Munksgaard.