Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2022, vol. 94, pp. 87–109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2021.94.56

Infodemic and the Crisis of Distinguishing Disinformation from Accurate Information: Case Study on the Use of Facebook in Kosovo during COVID-19

Gëzim Qerimi

University of Prishtina, Kosovo

gezim.qerimi@uni-pr.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1338-6956

Dren Gërguri

University of Prishtina, Kosovo

dren.gerguri@uni-pr.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2347-4685

Abstract. Social media over the years has been shown to be an important source for information in times of crisis and confusion. Citizens who were restricted to their homes due to pandemic-mitigating lockdowns have desired more than ever to be informed about the pandemic, have been exposed to a host of misinformation, which has also affected their trust in the media, as well as the way they have been informed about COVID-19 in the days following. This research aims to analyze how citizens have used the media during COVID-19 and whether they were capable to accurately distinguish misinformation or disinformation from accurate information. To respond to the research question and to test hypotheses a survey based on purposive sampling method was used with citizens that included 850 respondents from the seven main regions of Kosovo. Results of this study indicate that the information-seeking habits have changed within a short period of time and Kosovo society can easily be affected by disinformation. The data demonstrated that citizens failed to distinguish between false and true news. The results also highlight that education and economic situation were significant indicators, with less educated people, and people with the weakest economic well-being are more likely to believe false information.

Keywords: Audience, COVID-19, Disinformation, Infodemic, Media

Infodemija ir dezinformacijos atskyrimo nuo tikslios informacijos krizė: „Facebook“ naudojimo Kosove COVID-19 metu atvejo analizė

Santrauka. Metams bėgant socialinės medijos buvo svarbus informacijos šaltinis krizės ir sąmyšio metu. Žmonės, kurie dėl pandemijos turėjo likti namie, susidūrė su daugybe dezinformacijos, kuri taip pat paveikė jų pasitikėjimą medijomis bei požiūrį į COVID-19. Šiuo tyrimu siekiama išanalizuoti, kaip žmonės naudojosi medijomis COVID-19 metu ir ar jie gali tiksliai atskirti dezinformaciją nuo tikslios informacijos. Siekiant patvirtinti hipotezes buvo atlikta tikslinės atrankos metodu pagrįsta žmonių apklausa, kurioje dalyvavo 850 respondentų iš septynių pagrindinių Kosovo regionų. Tyrimo rezultatai atskleidė, kad informacijos ieškojimo įpročiai per trumpą laiką pasikeitė ir Kosovo visuomenė gali būti lengvai paveikta dezinformacijos. Duomenys parodė, kad žmonės nesugebėjo atskirti melagingų nuo tikrų naujienų. Rezultatai taip pat parodė, kad švietimas ir ekonominė padėtis buvo reikšmingi rodikliai žemesnio išsilavinimo žmonėms, o prasčiausią ekonominę gerovę turintys žmonės labiau tiki klaidinga informacija.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: auditorija, COVID-19, dezinformacija, infodemija, medijos

Received: 2022-09-14. Accepted: 2022-12-29.

Copyright © 2022 Gëzim Qerimi, Dren Gërguri. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Kosovo had the highest percentage of households with Internet access at home in the region (93%) (Eurostat 2019), which is the highest in the region and higher than the EU average (89%). According to a report on Internet Penetration and Usage in Kosovo, 93% of Kosovo citizens use the Internet for communication (STIKK 2019), and there are 1.10 million social media users (61.1% of the total population) in Kosovo in January 2020 (Datareportal, 2020). These data are indicative of the role of the Internet and social media in Kosovar society. Being the country with the youngest population in Europe, it is expected to have such a large use of the Internet. This has influenced institutions or media to give great importance to their presence on social media platforms, reaching millions of followers on Facebook pages (Hoxha, 2020). During the pandemic, health institutions or field experts were very active by posting daily messages with various information about COVID-19 (Gërguri, 2021). In addition, this affected the information-seeking habits of the citizens. The newspaper was one of the most trusted sources in Kosovo (Gërguri, 2016), however, the economic crisis as a consequence of the pandemic has left Kosovo without printed daily newspapers. On the other side, citizens turned to online media, especially during the lockdown, and as a result, the number of online media has increased. Kosovo was among the last European countries to be hit by COVID-19, being able to learn from other countries’ mistakes, and the government was able to take preventative action. Even though institutions were active on social media, especially on Facebook, keeping the public informed proved challenging. Tackling disinformation and misinformation has been shown a difficult challenge for Kosovo, and regardless of those factors, such as the youngest population, the high internet penetration, the high trust to television, and the last to be hit by the pandemic, disinformation and misinformation cannot be prevented.

The coronavirus pandemic crisis (COVID-19) has increased the demand for information and at the same time has demonstrated the vital role of the media in such situations. Since the reporting of COVID-19 began, a significant amount and varied misinformation has been circulated. Facebook played a crucial role during this period, especially in countries where is the dominant social media, such as India, USA, Brazil, and so on (Statista 2022). Due to a large amount of misinformation about the pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) began to use the term ‘infodemic’ to label the information disseminated about COVID-19. WHO Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated at the Munich Security Conference on 15 February 2020, “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic” (Zarocostas, 2020). While facing pandemic, people are dealing with the information overload, making it difficult for some of them to identify credible and trusted resources. This new situation and the health crisis effected the way citizens used Facebook and other social media, and their information-seeking habits. In this way, infodemic is the disease that has infected information with untruths. This misinformation, above all, has caused panic among the citizens, while as a result of the tendency of the citizens to spread any information they read, unverified and often false, the information has penetrated into an even wider public. Misinformation or disinformation has always been in societies, but in the social media age, they are intensified and can circulate at a great rate. In addition to this, almost anyone can produce and distribute information. Education, gender, economic and social situation could be one of the factors that impacts citizens’ habits as information consumers and users as well. Carroll (2020, p. 291) says that as consumer habits have changed, so has the way information is evaluated. Today, people tend to get information that corresponds to their worldview, ignore dissenting opinions, and form polarized groups about a story (Gërguri, 2021b; Pomerantsev, 2019). In addition, if the polarization is high, disinformation or misinformation can easily spread, as stated by Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) and can be a serious threat in terms of transmission and opinion formation (Shahi et al., 2020). This research aims to analyze how citizens have used the media during the crisis, where they capable to distinguish false from real information and three hypotheses have been raised.

H1: The use of Facebook by citizens of Kosovo area increased at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemics. This claim will be tested by measuring the use of Facebook by the respondents as a source of information about the COVID-19. With the survey data of this study it can be argued whether people’s use of Facebook increased during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemics. Facebook is one of the main social media used for spreading disinformation.

H2: The crisis of credibility in television by the citizens of Kosovo has made social media the main source of information. This claim will test whether television continues to have the same power in society. By measuring the use of television and its credibility to the public, and comparing it with social media, it can be concluded whether television is still the most used source in the country.

H3: The lower participants’ education level, the more likely they are unable to accurately discern misinformation and/or disinformation from accurate information. This claim will test if education affects the way citizens analyze media content. Crossing the education data with the answers of the respondents, we will see what role schooling plays in the way they receive information.

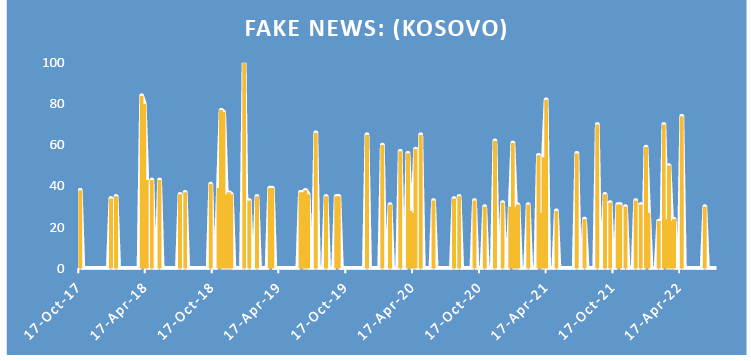

A Google Trends analysis reveals that this term began to gain relevance in Kosovo Google searches usually around the time of the elections. Apart from the period of election campaigns, the emergence of the pandemic was the time when fake news had a high frequency of use.

Figure 1. The frequency of ‘fake news’ for the territory of Kosovo in Google Trends (2017–2022).

Source: Google Trends, accessed July 20, 2022, https://www.google.com/trends

Nonetheless, the potential impact of focused efforts against misinformation makes it worthwhile to research its consequences in greater depth. Shahini-Hoxhaj’s (2018) study shows how false maps and a propagandistic agenda were viral on social media and polarized Kosovo’s society regarding the issue of Kosovo-Serbia dialogue. In this regard, the European Commission (2018) has specifically called attention to unequal susceptibility forms to information disorders, “from one society to another, depending on education levels, democratic culture, trust in institutions, the inclusiveness of electoral systems, the role of money in political processes, and social and economic inequalities”.

Literature Review

Disinformation and Misinformation

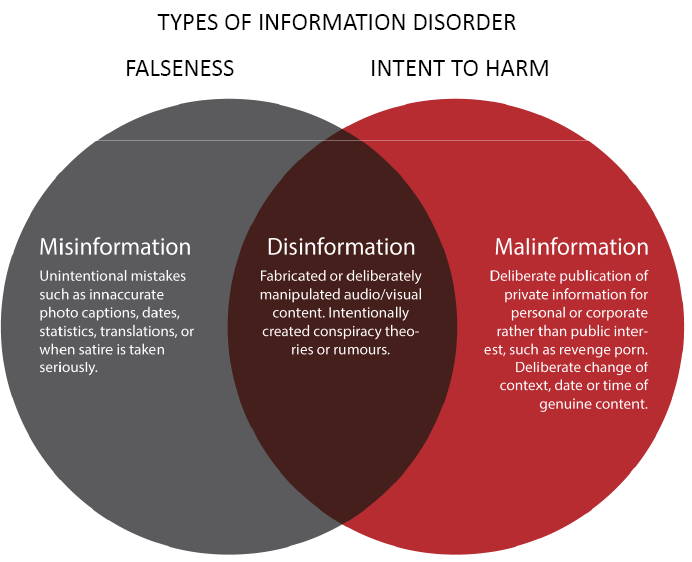

A report of the European Commission (2018) recommended disinformation, as an alternative to the term “fake news”, while Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) were even more precise and distinguished three types of information disorder, “Mis-information is when false information is shared, but no harm is meant. Dis-information is when false information is knowingly shared to cause harm. Mal-information is when genuine information is shared to cause harm, often by moving information designed to stay private into the public sphere” (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017, p. 5).

Figure 2. Information disorder. Source: Wardle and Derakhsan (2017, p. 5)

Disinformation or misinformation may travel quickly from one person to another nowadays, and after the age of post-trust (Löfstedt, 2005), societies are now faced with the era of “post-truth” (Higgins, 2016; Newman, 2023; Harambam et al., 2022) or “new boom in lying” (van Dyk, 2022). “Post-truth” was declared the word of the year in 2016 by the Oxford dictionaries, reflecting “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal beliefs” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016). A large area of academic study now centers on the analysis of how misleading information spreads, particularly through social media and internet (Mustafaraj & Metaxas, 2017; van der Linden et al., 2017). Disinformation has been argued to have a substantial impact on political campaigns and discourse (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Jacobson et al., 2016), however, there is some disagreement regarding how much disinformation or misinformation, including social media “echo chambers” and “filter bubbles” impacts public opinion (Shao et al., 2017). Spreading disinformation has the potential to harm society and science (Lewandowsky et al., 2017) and threatening democracy, polarizing society, and putting the health and security of citizens at risk (Diaz & Nicolas-Sans, 2021). This has been expressed several times since the outbreak of the pandemic, because disinformation influenced the public’s belief initially about the existence of the virus, its effects, the effects of vaccination and so on. Social media was also a channel that experts used to communicate directly with the citizens, being an effective tool for raising public awareness and transmitting important information (Alnuhayt et al., 2022).

Research on COVID-19 is on the rise, and one of the most crucial subjects of conversation is disinformation and infodemic. More research on COVID19-related online disinformation has a specific regional (Fernandez-Torres et al., 2021; Moscadelli, 2020; Molina et al., 2022), linguistic (Rovetta-Bhagabathula, 2020), cross-platform (Tagliabue, 2020), or information-sharing behaviour (Rodriguez et al., 2020; Pehlivanoglu et al., 2021) as its focus. The research involving more than 1,600 participants (Pennycook et al., 2020) looked into why people distribute COVID-19 disinformation and trust it. Their research demonstrates how many people just are unable to evaluate the accuracy of the news before sharing it. A significant amount of research demonstrates that disinformation has a particular style intended to boost arousal and is disseminated on social media more quickly (Lazer et al., 2018; Shu et al., 2020) and in larger cascades than factual information (Juul & Ugander, 2021).

Information Behavior during Health Crisis

Being well-informed about COVID-19 was very important for every society and this emphasizes the significance of information in health crises. People have experienced a variety of information-related phenomena during the pandemic dealing with daily issues including determining the reliability and validity of information. In times of crises, information behaviour is an important factor and according to WHO, this is crucial for developing proper reactions (PAHO 2020). Information behaviour is “the totality of human behavior in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information-seeking, and information use” (Wilson, 2000, p. 49).

Information behaviour was challenged permanently by the dissemination of disinformation and misinformation, highlighting the importance of media literacy in society, as an appropriate approach to address the infodemic. Information seeking typically refers to a person’s endeavour to get deeper understanding of any issue or feature. The information might be actively or passively sought. The purposeful or intentional search for information to meet a goal is known as active information-seeking, while passive seeking means the acquisition of information unintentionally or accidently (Wilson, 2000).

According to studies on health information-seeking, behaviour varies when it occurs within a social context of mutual support and engagement, therefore it changes the way people do the search and use of information (Abunyewah et al., 2020; Meadowbrooke et al., 2014). In times of crisis, interest in getting information increases and when the challenge is health, then the main goal of people is to be informed to protect their health and the people around them. The study by a group of researchers at Nottingham Trent University shows how “social media platforms’ role in sharing news was perceived to have good intentions, and created an atmosphere of people looking out for one another” (Hadlington et al., 2022, p.11). As Gonzalez-Padilla and Tortolero-Blanco (2020) conclude, social media could have a crucial role to spread important information in times of health crisis. Other authors emphasized the necessity of reputable social media users (e.g. influencers, expert of the field) in various positions in the fight against COVID-19 (Govender et al., 2021; Mourad et al., 2020). This has been the practice of some experts of infectology in Kosovo, Lul Raka and Valbon Krasniqi, both were influential in Kosovar society. During this time, also the Institute of Public Health, as well as the Ministry of Health, very quickly turned their page into Facebook, the main addresses of citizens to receive information from this institution. Thus, social media made it possible to distribute necessary information, especially in the period when there was a lot of ambiguity and misinformation in circulation.

Credibility

“In times of crisis, people turn more to television” (Eddy & Fletcher, 2022) and this does not happen because of the speed of information, but because of credibility (Mehrabi et al., 2009). The concepts of credibility and believability or trust were found to be similar (Edelstein & Tefft, 1974; Metzger and Flanagin, 2008; Jackob, 2010). Others, however, saw credibility as having more than one dimension and as having multiple dimensions. Rather than being an objective indicator of the source, the definition of credibility was introduced as a perceptual variable (Flanagin & Metzger, 2007). There have been concerns about the credibility of the media because the most trustworthy media have more influence over people. Media credibility is the extent to which the public understands the news source. The focus of media credibility research is primarily on the mainstream media, such as television or newspapers. By asking participants to rate how much they believe the information to be accurate, authentic, and credible, it is possible to gauge the credibility of the media. Therefore, people’s opinions regarding the accuracy of the content can be used to gauge the media’s credibility.

The trustworthiness of the source, on the other hand, is an important factor in the communication process, and researchers (Golan, 2010; Bae et al., 2001) mostly concentrate on the persona. This is even more apparent in the age of social media, where Facebook is one of the main sources of information and people’s trust also depends on the mutual relationship. “Social media is more important now than ever, but we must be aware of the potential limitations. Health care providers have been leaders on the front lines of this crisis since the onset. It is important to be leaders in social media as well” (Gottlieb & Dyer, 2020).

In addition to altering how individuals stay connected, the introduction of social media has had a profound influence on daily life by raising problems for governments and society (Fuchs, 2014). Particularly, the popularity of multiple social platforms for interacting and reaching out to people around the world has led to disinformation and misinformation receiving more and more attention in recent years (Fedeli, 2020). Furthermore, this manipulated information sometimes is disseminated even faster than the real information through various social media. Unaware users may mistakenly believe that the material is trustworthy simply because it is repeated so frequently when they obtain the same false information from several sources. Because of this, it is crucial to look at potential strategies for helping users in determining the degree of reliability of online content.

Social media users are changing how they interact with one other, gather information, and use it to make decisions for their personal and professional lives. Spreading disinformation, changing beliefs on specific issue and polarization are some of the current challenges that social media has caused to societies. According to Li and Suh (2015), the message credibility and the medium credibility both have a substantial impact on the information credibility of social media. COVID-19 showed us how information can create dilemma, because a lot of people looked up pertinent information regarding the pandemic. The large circulation of verified information, but at the same time unverified and false, leads to the infodemic.

Methodology

To respond to the research question and to test hypotheses, the purposive sampling method and survey with citizens will be used. A questionnaire consisting of twenty-seven questions, in addition to the demographic characteristics (age, gender, residence, and employment status), was designed for this study and created on Google Form. It was widely disseminated online, particularly through social media and instant messaging services such as Viber. First, people were selected from the seven major regions of Kosovo and then with the snowball technique (Crouse & Lowe, 2018) the questionnaire was distributed further, making sure that the sample is comprehensive for Kosovo. The anonymous survey link was shared on Facebook, Viber and WhatsApp groups, and participants were encouraged to complete it and share the links with others in their networks. This procedure was repeated until the necessary number of replies was reached. The snowball sampling was chosen because the survey was conducted in the period of lockdown and this technique is useful when the respondent is harder to reach (Baltar & Brunet, 2012). The questionnaire consisted of several parts: at the beginning, the participants were introduced to the aims of the study and asked to agree to the data privacy statement. The data privacy statement informed participants that anonymity is assured, how the collected data is being stored, who has access to the data, precautions for data protection and the participants’ rights regarding the gathered data in accordance with the European Data Protection Regulation. This was followed by questions on demographic data, such as age, gender, education, profession, employment and residence. After that, they were asked about how they consumed news before COVID-19 and how they were consuming news during COVID-19 (the results are shown in Figure 3 within the results section). In this study, the focus is on the active way of information-seeking and Kosovo citizens were asked for this kind of information behaviour. Second, they were questioned about trust of their sources of information, whether the level of trust has changed during the pandemic, and how satisfied they were with the amount of information about COVID-19. Third, in addition to the questions, the survey participants also read eight news headlines that have been published in different media during the time of COVID-19. Four of them were disinformation or misinformation, categorized according to Wardle’s (2017) typology. The major goal of the questionnaire was to determine how Kosovars inform themselves on things related to COVID-19, to identify the main routes of communication they use, and to learn about the consequences of disinformation and misinformation. The questionnaire was conducted from April 27 to May 3, 2020. This electronic questionnaire included 850 respondents from the seven main regions of Kosovo.

Table 1. Demographic data of respondents

|

Gender |

||

|

|

Woman |

491 |

|

|

Man |

359 |

|

Residence |

||

|

|

Rural |

326 |

|

|

Urban |

524 |

|

Age |

||

|

|

18-25 |

340 |

|

|

26-35 |

236 |

|

|

36-55 |

180 |

|

|

56-65 |

93 |

|

Status employement |

||

|

|

Unemployed |

503 |

|

|

Employed in the private sector |

175 |

|

|

Employed in the public sector |

133 |

|

|

Self employed |

39 |

|

Total |

850 |

|

Information-seeking Habits

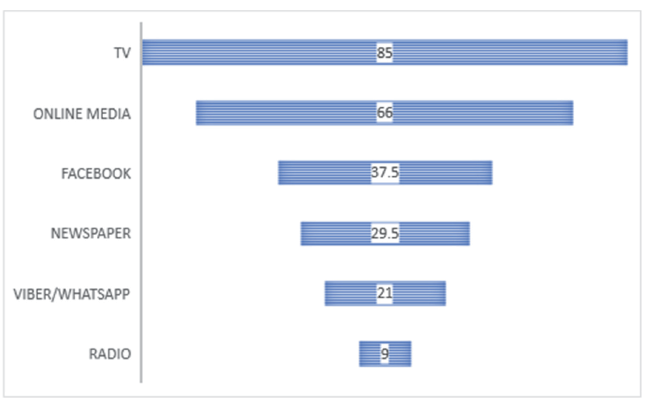

Sharing information is essential in a global crisis. As demand for information about COVID-19 increased, so did the circulation of COVID-19-related information in various media. Journalists were among those who risked their health to report from the field and trying to provide the public with the latest pandemic-related news. However, in this period, information was also disseminated by those who do not understand journalism and media. This caused a lot of disinformation or misinformation, which also reached a large number of people. The Internet and online micro targeting methods have enabled to create and share messages that are tailored to specific persons. Online media is the second main source of Kosovo citizens and 66% of the Kosovar adults say they receive news on different online media, while almost 40% of them use social media in their information-seeking behaviour. Facebook is the most popular social media used in Kosovo (Zeneli, 2021). In this social media, users can get news through their friends or by subscribing to a news organization’s feed or other public pages. According to Mutz & Young (2011, p.1038), “one extremely important way [individuals] decide what to pay attention to is through recommendations that reach them through their online social networks”.

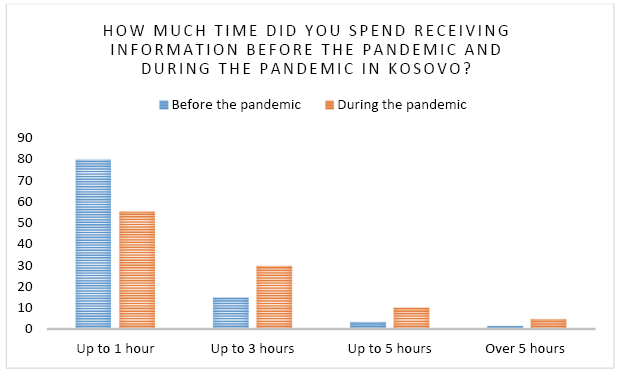

In Kosovo, about 70% of the society indicated that they were concerned about the spread of the pandemic, while 65% of respondents were informed up to five times a day about COVID-19. The graph shows the difference between informing the society before the outbreak of COVID-19 in Kosovo and after the early months of COVID-19. Most stated that the time spent receiving information prior to the pandemic was one hour or less per day, but there is an increase in those who spent more time receiving information after the appearance of COVID-19. Out of 5% who have spent up to 5 hours or over 5 hours during the day being informed, this percentage has tripled after the appearance of COVID-19, reaching 15%. This demonstrates the growing interest in obtaining more information in Kosovo society.

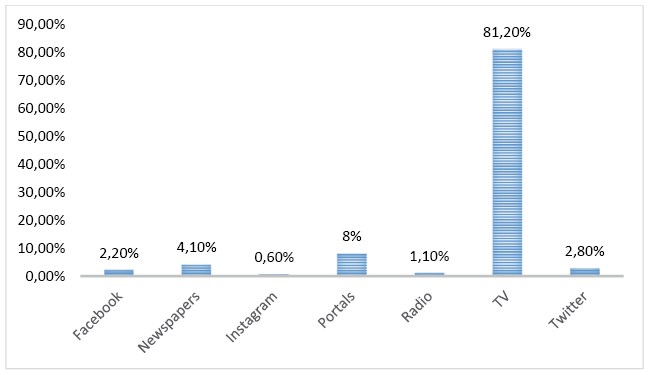

Figure 3. Information-seeking habits

In all this interest, undoubtedly the citizens spent even more time being informed by the dominant media in society, television. The announcements or press conferences of health institutions were the information that interested most for the citizens of Kosovo. The main source of information in Kosovo remains television (85%), followed by online media (66%). Kosovo is among the countries, along with Germany (Nielsen et al., 2020) and Romania (Corbu, 2020) where television continues to be a more important source of information than online media, while in the United Kingdom, the United States America, Spain, Argentina and South Korea, online media has already won the ‘battle’ with television to be the main source of information (Nielsen et al., 2020). Television as a source of information is used moderately and by many respondents, while most of them have not used the other two traditional media at all, radio and newspaper. The news websites or online media were addressed moderately widespread in Kosovar society. What stands out is the small percentage of those who are informed through messages received on Viber or WhatsApp, as well as Facebook posts by strangers (7.7%), two of these are the most common forms of misinformation dissemination in Kosovo.

Figure 4. Sources of information of citizens

In Kosovo, citizens, depending on the level of education, prefer to be informed on television than in other media. A chi-square test between the level of education and choosing television to get information shows that both variables are correlated, and there is a significant association between the variables (Χ2(1) = 23.097, p = 0.027).

Table 2. Information source

|

Information source |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig |

|

TV |

23.097 |

12 |

.027 |

|

Radio |

36.826 |

12 |

.000 |

|

Family and friends |

22.873 |

12 |

.029 |

|

Viber & WhatsApp |

25.766 |

12 |

.012 |

|

Friends posts on Facebook |

20.816 |

12 |

.053 |

|

Page and Group posts on Facebook |

20.278 |

12 |

.062 |

|

Newspaper |

14.116 |

12 |

.293 |

|

Colleagues |

58.259 |

12 |

.000 |

|

Online Media |

13.804 |

12 |

.313 |

|

Unknown people’s posts on Facebook |

20.506 |

12 |

.058 |

|

Government Press Conference |

36.466 |

12 |

.000 |

|

Health Institution |

82.966 |

12 |

.000 |

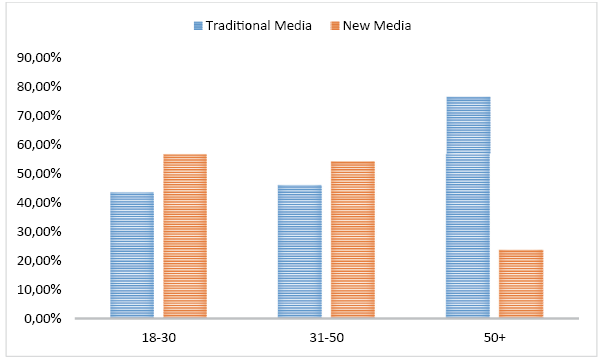

Meanwhile, age is a factor that distinguishes the citizens of Kosovo in how they are informed. While seniors prefer to get information on TV, this varies among young people up to the age of 30, who during the quarantine period were more often informed in new media, online and social media, than in traditional media. This result is also due to the extension of television programs on social media. Kosovar television channels have used Facebook constantly to broadcast content on this social media. This content includes but is not limited to news editions, debating shows, and even government press conferences. This also coincides with the responses of respondents under the age of 30, who trust TV more than the new media.

Figure 5. Media source by age

Trust in Different Sources in Times of Crisis

In times of crisis, citizens tend to use more traditional media and trust them more. It is surprising that online media, which is the second main source of information, does not have reliability more than 8%. According to NDI Public Opinion Poll (2020), 81% of citizens in Kosovo believe that online media regularly or occasionally reports false information. This is one of the factors why citizens do not have trust in online media. The lack of trust in online media was highlighted also by NDI Public Opinion Poll (2020). Because of the numerous sources from which content might come, judging the reliability of social media remains challenging (Johnson & Kaye, 2014). Users might evaluate the message sender when judging Facebook postings with connected news or information. Perceptions of a message sender’s honesty and expertise can serve as heuristic clues for determining whether the material received from that source is valuable and reliable. The reliability of the friend who shared the link is one potentially important and constantly available clue concerning the reliability of various media sources. The trustworthiness of the page that posted the information is another indicator.

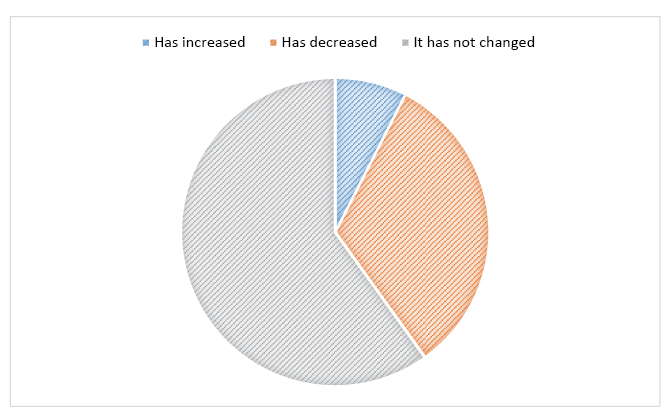

Figure 6. Trust in media during crisis

Reliability in the sources of information is very important, especially in times of crisis. During crises, credibility in the media can fluctuate (McDougall, 2019). In Kosovo, around 30% of citizens believe that trust in the media has decreased as a result of the way journalists report, as well as dubious or untrue information that was circulating during the pandemic period. However, most of them (59.9%) think that reliability has not changed during the health crisis.

Figure 7. Trust level in media during the pandemic

Disinformation/Misinformation and Dissemination on Social Media

Since the beginning of COVID-19, a large quantity of disinformation or misinformation arose and quickly disseminated throughout the world. Vosoughi et al. (2018) found that disinformation and misinformation were shown to be more likely to elicit feelings such as fear, surprise, and disgust than true information, which elicited emotions such as anticipation, grief, and joy.

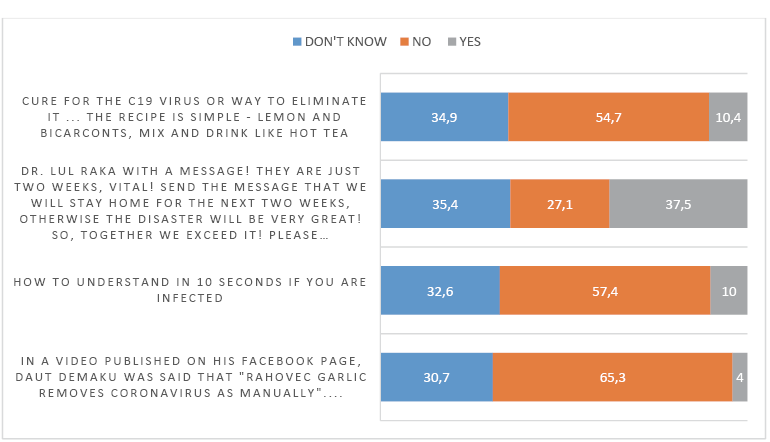

Kosovar society was not immune to the large amount of misinformation that circulated everywhere, especially on social media. “Many kinds of disinformation began to circulate as soon as the first reports about coronavirus emerged, mainly on social media” (Gërguri, 2020a). A study of the quarantine period in 2020 (Gërguri et al., 2020) shows that the interactivity was high, especially for certain disinformation and misinformation that went viral on social media. Some disinformation and misinformation were selected for this paper’s survey, to measure whether the citizens of Kosovo have fallen prey to manipulation or have the necessary skills to protect themselves from misinformation. Citizens were faced with a lot of misinformation that was global because most of them were published in English and then translated into Albanian. Brennen et al. (2020) found that 38% of the misinformation about COVID-19 on social media was entirely made-up, and most of the misinformation was formed by misleading and manipulating the true information. Rumors and misleading information are more likely than true information to be shared on social media (Sommariva et al., 2018). Quarantine is one of the factors that has heightened the influence of information from social media, because people have spent more time on their phones (Gërguri, 2021a).

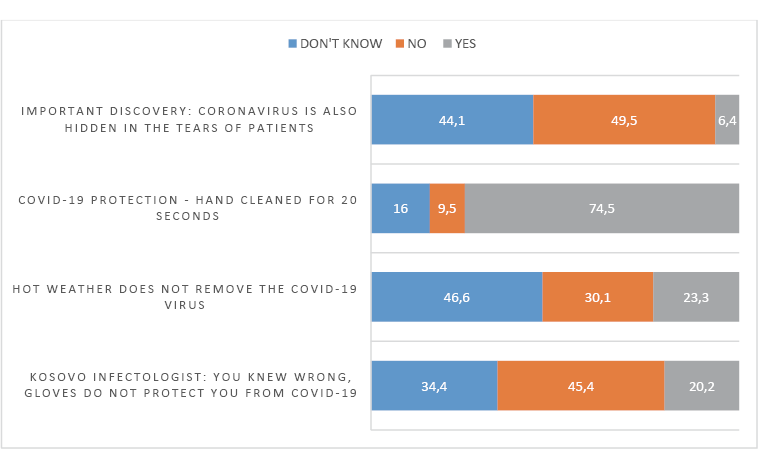

Figure 8. False news used in the Survey

The information most trusted by the respondents, despite being false, was a message that they believe was spread by a local expert, Dr. Lul Raka. The false information spread, which required staying at home to avoid a catastrophe, was denied by Raka himself, however it had gone viral and despite the denial by the doctor, turned out to have been trusted by the citizens. Most of them were not sure that this was a disinformation. Thirty-seven percent of respondents believed this disinformation while 35% of them answered that they do not know whether it is true or not. Moreover, 34% of respondents also felt secure to share the information, because they believed it is true. This is a result of lack of institutional initiatives to address the issue of media literacy (Jahiri, 2020), which would help people to have a higher ability to critically evaluate information. This issue is concerning all European countries and as it is raised in another study (Buturoiu, 2021, p. 138), “is a timely and extremely important effort in the increasingly complex information ecosystem”. Therefore, it is very important to increase media literacy skills among citizens, in order to combat disinformation and misinformation.

Bago et al. (2020) found that encouraging social media users to think about the accuracy of information can have positive consequences in reducing beliefs about disinformation and misinformation. However, what makes people more sensitive to information is the fact that they did not even believe in real news. Instead than verifying the accuracy of the information, people support their decision-making actions based on prior knowledge of what should be right (Hadlington et al., 2022). Citizens of Kosovo were in a situation where they were not sure what to believe. Of the 4 true pieces of information they read in the questionnaire, only one of them seemed credible to them, the one that talks about hand cleaning as one of the ways to protect against COVID-19. This was the only information that most of respondents (59.2%) show readiness to disseminate with others. Meanwhile, other information, despite being true, was not trusted by almost half of the respondents.

Figure 9. True news used in the Survey

Considering that a person always acts based on the information he receives and above all, on the information he trusts, then in the case of Kosovar society, there seems to have been a confusion among the citizens because they suspected even the information that was in fact truth. As Glik (2007) highlights, reactions to crises are determined by perceptions of danger rather than real risk.

A big challenge during this period was the involvement of citizens in the dissemination of information, often unverified information. Merchant et al. (2011) conclude that in addition to the difficulties in determining the authenticity of information, it is sometimes impossible to identify people who disseminate newsworthy information. More than half of the respondents said they had received information from their friends or family members that was later found to be false. This also indicates the information-seeking habits, because citizens in Kosovo seek information in different sources, as this research found. Over 70% of respondents stated that if they have doubts about information, they look for it in another media. Less than 10% use Facebook (friends, pages or groups), or other social media to verify the information. This was used as an information-seeking measure based on items that were asked in the survey.

Education, gender and economic situation were statistically significant indicators, with less educated people, women and people with the weakest economic well-being are more likely to believe disinformation and misinformation. Given research indicating that less educated people were more unsure which information is true and which is false, it is plausible that less educated people are more vulnerable to online influence. The higher level of education, the more likely is to detect disinformation and misinformation (Jones-Jang et al., 2021). This is proven in Kosovo case, because respondents with less education have shown less media literacy skills, therefore they are more vulnerable to manipulated information. Similar findings were also showed in a research of internet users from US, France, Poland, UK, Spain, Germany and Italy (Dutton & Fernandez, 2019). On the other side, more educated people are more careful when they choose their information sources. A study of the Pew Research Center (2020) found that those with more education are often more convinced of their capacity to verify news. Pennycook and Rand (2019) used a Cognitive Reflection Test and conclude that those who are more adept at analytical thinking are less prone to being misled than those who put less effort into it. In another study it is showed that when it comes to disseminate disinformation, men expressed a larger tendency of sharing (Buchanan 2020, p.11). In Kosovo, gender was found to be another important variable, however in contrast with Buchanan research, in Kosovar society, women had higher rated likelihood of sharing dubious or untrue information. On the other hand, economic situation was discovered to be a crucial element, with people having the poorest economic situation expressing a larger risk of believing disinformation and misinformation than people with better economic situation. This was also highlighted by Dutton and Fernandez (2019) in their study among internet users from seven countries.

Conclusions

Media plays a crucial role in conveying the intricacies of a crisis, in addition to shaping public opinion and influencing people’s beliefs about the crisis. The results show that respondents were absolutely interested in all the information about COVID-19. Since the onset of COVID-19, the percentage of people who spent five or more hours per day receiving information tripled to 15%. Data showed that the use of Facebook has increased at the beginning of COVID-19, which confirms H1. However, higher information consumption does not mean that they have been better informed (Gerosa et al., 2021), due to the greater time spent on social media. But it shows how the information-seeking habits has changed within a short period of time.

As for reliability, TV is considered the main and most reliable source of information, while data expose a substantial lack of trust of the new media in general. By measuring the use of television and its credibility to the public, it can be concluded that television continues to be the most powerful media in the country (H2 is incorrect).

The findings that citizens failed to distinguish between false and true news, show that Kosovo society, which has this high percentage of internet access, is not capable of distinguishing false news from true, and can easily be affected. The results of the Raka case is one of the indicators that shows how such disinformation has been taken for granted by citizens.

It may be crucial to identify particular audiences that are especially susceptible to the impacts of misinformation when developing tactics to combat such effects. The hard time of distinguishing misinformation and disinformation from accurate information is indicated also by studies in other countries (Luo et al., 2021). In Kosovo case, it can be concluded that it is education and economic situation, with less-educated people and those who have weaker economic well-being that has a higher probability of not being able to distinguish misinformation and disinformation from accurate information (H3 is correct). For at least two key reasons, it is crucial for citizens to accurately identify false information. First of all, individuals will be able to better respond to misinformation and disinformation if they can distinguish between false and true information, for instance, by ignoring such misinformation or disinformation, alerting those nearby to untruths, seeking out further details, or even reporting it to the platform from which it was disseminated. These responses might lessen the overall effect of misinformation and disinformation. Second, the ability to distinguish between information that is true and untrue may help people place more faith in information that is real. Because individuals may mistake misinformation and disinformation for accurate information, being able to distinguish between the two may help to increase public confidence in the veracity of information.

One of the most serious types of crises is a pandemic. COVID-19 was accompanied by even more misinformation, which has made it even more difficult to deal with it. Due to the breadth and depth of the impacts and the need to comprehend the skills necessary to lessen the damage, it is beyond the control of any actor and is intrinsically difficult. Social media, on the other hand, enables a wide range of actors to actively participate in crisis communication as consumers, providers, and disseminators of knowledge. COVID-19 was a new type of virus, therefore there was also scientific doubt regarding its susceptibility and severity, prevention, treatment, etc. During the pandemic, there was a dearth of information and high degrees of uncertainty. In all of this, the use of social media by citizens was very important, the way they use social media and the impact they had on them. This is even more important to research in a society like Kosovo, where the young age dominates and the use of the Internet is at a high level.

The finding of different studies (Jones-Jang et al., 2021; Dutton & Fernandez, 2019; Buchanan, 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2019), including this study, shows that citizens find it difficult to distinguish the false information from the real one, and do not even trust the real news, thinking that they are false. This indicates that institutions should work to be more effective and more trustful source for the citizens, should try to collaborate with social media platforms to combat disinformation and with local fact-checkers in order to limit the spread of untrustworthy information and, in the long terms, to include media literacy as an obligatory subject in elementary and high schools, as well as using informal education, workshops, and libraries to give the people the necessary skills. The inclusion of Media Literacy is already happening across Europe, an example that Kosovo and other countries from Western Balkans must follow too. In Kosovo, Media Literacy is an elective subject in high schools, while is not part of curriculum in elementary schools.

Citizens will not be completely empowered until they are able to spot misinformation or disinformation, and make right decisions regarding health-related issues or other issues. Media literacy should be seen as vital ability in the greatly digitalized society we live in. They ought to be presented as essential lifetime skills that, once mastered, may be used to address any information-related issue.

References

Abunyewah, M., Gajendran, Th., Maund, K., & Okyere, S. A. (2020). Strengthening the information deficit model for disaster preparedness: Mediating and moderating effects of community participation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 46, Article 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101492

Alnuhayt, A., Mazumdar, S., Lanfranchi, V., & Hopfgartner, F. (2022). Understanding reactions to misinformation - a COVID-19 perspective. In ISCRAM 2022 Conference Proceedings - 19th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management. 19th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM 2022), Tarbes, France (pp. 687–700). ISCRAM Digital Library.

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Bago, B., Rand, D. G., & Pennycook, G. (2020). Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(8), 1608–1613. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xge0000729

Baltar, F., & Brunet, I. (2012). Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Research, 22(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241211199960

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F., Howard, P. N., & Nielsen, R. N. (2020). Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation

Buchanan, T. (2020). Why do people spread false information online? The effects of message and viewer characteristics on self-reported likelihood of sharing social media disinformation. PLOS ONE, 15(10), Article e0239666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239666

Buturoiu, R., Udrea G., Oprea D.-A., & Corbu, N. (2021). Who Believes in Conspiracy Theories about the COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania? An Analysis of Conspiracy Theories Believers’ Profiles. Societies, 11(4), Article 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040138

Carroll, B. (2020). Writing and Editing for Digital Media. 4th edition. Routledge.

Corbu, N., & Buturoiu, R. (2020). Navigating the Romanian ‘Infodemic’: A Replication of the Reuters Study on Accessing and Rating News and Information about Coronavirus. YouCheck Project.

Crouse, T., & Lowe, P. (2018). Snowball sampling. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation (pp. 1531–1532). Sage.

Datareportal. (2020). Kosovo Digital 2020. Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-kosovo

Diaz, J. B., & Nicolas-Sans, R. (2021). COVID-19 and Fake News. Encyclopedia, 1(4), 1175–1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1040088

Dutton, W. H., & Fernandez, L. (2019). How susceptible are Internet users? Intermedia, 46(4), 36–40.

Edelstein, A. S., & Tefft, D. P. (1974). Media credibility and respondent credulity with respect to Watergate. Communication Research, 1(4), 426–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365027400100406

Eddy, K., & Fletcher, R. (2022). Perceptions of media coverage of the War in Ukraine. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/perceptions-media-coverage-war-Ukraine

European Commission. (2018). Tackling online disinformation: a European Approach. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0236&rid=2

Eurostat. (2019). Key figures on enlargement countries. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/9799207/KS-GO-19-001-EN-N.pdf/e8fbd16c -c342-41f7-aaed-6ca38e6f709e

Fedeli, G. (2020). Fake news meets tourism: a proposed research agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, Article 102684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.02.002

Fernández-Torres, M. J., Almansa-Martínez, A., & Chamizo-Sánchez, R. (2021). Infodemic and Fake News in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), Article 1781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041781

Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site features, user attributes, and information verification behaviors on the perceived credibility of web-based information. New Media & Society, 9(2), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807075015

Fuchs, Ch. (2021). Social Media: A Critical Introduction (3rd ed.). Sage.

Gërguri, D. (2021a). Kosovo: Political Crisis, One More Challenge Alongside COVID-19. In D. Lilleker, I. A. Coman, M. Gregor, & E. Novelli (Eds.), Political Communication and COVID-19: Governance and Rhetoric in Times of Crisis (pp. 312–322). Routledge.

Gërguri, D. (2021b). Komunikimi politik në epokën e mediave sociale. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

Gërguri, D. (2020a). Kosovo: Coronavirus and the media. European Journalism Observatory (EJO). https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/kosovo-coronavirus-and-the-media

Gërguri, D. (2016). Political Power of Social Media in Kosovo. Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations, XIII, 1, 95–111. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2716628

Gërguri, D., Qerimi, G., & Blakaj, B. (2020). Coronavirus crisis disinformation on digital platforms: the case of Kosovo. https://medium.com/@DigiComNet/coronavirus-crisis-disinformation-on-digital-platforms-the-case-of-kosovo-c643076af911

Gerosa, T., Gui, M., Hargitta, E., & Nguyen, M. H. (2021). (Mis)informed during COVID-19: how education level and information sources contribute to knowledge gaps. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2196–2217.

Glik, D. C. (2007). Risk Communication for Public Health Emergencies. Annual Review of Public Health, 28(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144123

González-Padilla, D. A., & Tortolero-Blanco, L. (2020). Social media influence in the COVID-19 Pandemic. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology, 46(suppl.1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s121

Gottlieb, M., & Dyer, S. (2020). Information and Disinformation: Social Media in the COVID-19 Crisis. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 27(7), 640–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14036

Govender, E., Holland, K., & Lewis, M. (2021). Communicating COVID-19: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Springer.

Hadlington, L., Harkin, L. J., Kuss, D., Newman, K., & Ryding, F. C. (2022). Perceptions of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000387

Harambam, J., Grusauskaite, K., & de Wildt, L. (2022). Poly-truth, or the limits of pluralism: Popular debates on conspiracy theories in a post-truth era. Public Understanding of Science, 31(6), 784–798. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F09636625221092145

Higgins, K. (2016). Post-truth: a guide for the perplexed. Nature, 540(7631), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/540009a

Hoxha, A. (2020). Peisazhi i mediave në Kosovë: Ndikimet e urrejtjes dhe të propagandës. SEENPM.

Jackob, N. G. E. (2010). No alternatives? The relationship between perceived media dependency, use of alternative information sources, and general trust in mass media. International Journal of Communication, 4, 589–606.

Jacobson, S., Myung, E., & Johnson, S. L. (2016). Open media or echo chamber: the use of links in audience discussions on the Facebook Pages of partisan news organizations. Information, Communication & Society, 19(7), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1064461

Jahiri, M. (2020). Edukimi medial, e vetmja rrugë për ta mbrojtur shoqërinë nga lajmet e rreme dhe për t’i ruajtur vlerat demokratike të vendit. Epokaere.com. https://www.epokaere.com/edukimi-medial-e-vetmja-rruge-per-ta-mbrojtur-shoqerine-nga-lajmet-e-rreme-dhe-per-ti-ruajtur-vlerat-demokratike-te-vendit/

Johnson, T., & Kaye, B. K. (2014). Credibility of social network sites for political information among politically interested internet users. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 957–974. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12084

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406

Juul, J. L., & Ugander, J. (2021). Comparing information diffusion mechanisms by matching on cascade size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(46), Article e2100786118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2100786118

Lazer, D. M., et al. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Li, R., & Suh, A. (2015). Factors influencing information credibility on social media platforms: evidence from Facebook pages. Procedia Computer Science, 72, 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.12.146

Lilleker, D., Coman, I. A., Gregor, M., & Novelli, E. (Eds.). (2021). Political Communication and COVID-19. Governance and Rethoric in Times of Crisis. Routledge.

Löfstedt, R. (2005). Risk management in post-trust societies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Luo, M., Hancock, J. T., & Markowitz, D. M. (2022). Credibility Perceptions and Detection Accuracy of Fake News Headlines on Social Media: Effects of Truth-Bias and Endorsement Cues. Communication Research, 49(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921321

Lytvynenko, J. (2020, March 16). Here’s a Running List of the Latest Hoaxes Spreading about the Coronavirus. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/janelytvynenko/coronavirus-fake-news-disinformation-rumors-hoaxes

Meadowbrooke, C. C., Veinot, T. C., Loveluck, J., Hickok, A., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2014). Information behavior and HIV testing intentions among young men at risk for HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(3), 609–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23001

Mehrabi, D., Hassan, A. M., & Sham, M. (2009). News media credibility of the internet and television. European Journal of Social Sciences, 11(1), 136–148.

Merchant, R. M., Elmer, S., & Lurie, N. (2011). Integrating social media into emergency-preparedness efforts. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365(4), 289–291. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1103591

McNair, B. (2017). Fake News: Falsehood, Fabrication and Fantasy in Journalism. Routledge.

McDougall, J. (2019). Fake News vs Media Studies: Travels in a False Binary. Palgrave Macmillan.

Metzger, M. J., & Flanagin, A. J. (2008). Digital media, youth, and credibility. MIT press.

Molina, L., et al. (2022). Spread of Fake News About Covid: The Ecuadorian Case. In K. Arai (Ed.), Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 542 (pp. 672–678). Springer, Cham.

Moscadelli, A., et al. (2020). Article Fake News and Covid-19 in Italy: Results of a Quantitative Observational Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(16), Article 5850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165850

Mourad, A., et al. (2020). Critical impact of social networks infodemic on defeating coronavirus covid-19 pandemic: Twitter-based study and research directions. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, 17(4), 2145–2155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2020.3031034

Mustafaraj, E., & Metaxas, P. T. (2017). The fake news spreading plague: Was it preventable? In WebSci 2017 - Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Web Science Conference (pp. 235–239). https://doi.org/10.1145/3091478.3091523

Mutz, D. C., & Young, L. (2011). Communication and public opinion: Plus Ça Change? Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(5), 1018–1044. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr052

Newman, S. (2023). Post-Truth, Postmodernism and the Public Sphere. In M. Conrad, G. Hálfdanarson, A. Michailidou, Ch. Galpin, & N. Pyrhönen (Eds.), Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics. Populism, Disinformation and the Public Sphere (pp. 13–30). Palgrave Macmillan.

Nielsen, R. K., et al. (2020). Navigating the ‘Infodemic’: How People in Six Countries Access and Rate News and Information about Coronavirus. Reuters Institute Report. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/infodemic-how-people-six-countries-access-and-rate-news-and-information-about-coronavirus

NDI, Kosovo Public Opinion Poll (2020, August 11). https://www.ndi.org/publications/ndi-kosovo-public-opinion-poll-2020

Oxford Dictionaries. (2016). Word of the Year 2016 is... Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2020). Why data disaggregation is key during a pandemic. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52002

Parker, K., et al. (2020). Most Americans Say Coronavirus Outbreak has Impacted their Lives. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/03/30/most-americans-say-coronavirus-outbreak-has-impacted-their-lives/

Pehlivanoglu, D., et al. (2021). Fake News Detection in Aging During the Era of Infodemic. Innovation in Aging, 5(Suppl 1), 968–969. https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fgeroni%2Figab046.3489

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620939054

Pew Research Center. (2020). Americans who get news mostly through social media are least likely to follow coronavirus coverage. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/03/25/americans-who-primarily-get-news-through-social-media-are-least-likely-to-follow-covid-19-coverage-most-likely-to-report-seeing-made-up-news/

Pomerantsev, P. (2019). This is not propaganda: Adventures in the war against reality. Public Affairs.

Rodríguez, P. C., Villarejo Carballido, B., Redondo-Sama, G., Guo, M., Ramis, M., & Flecha, R. (2020). False news around COVID-19 circulated less on Sina Weibo than on Twitter. How to overcome false information? International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.17583/rimcis.2020.5386

Rovetta, A., & Bhagavathula, A. S. (2020). COVID-19-Related Web Search Behaviors and Infodemic Attitudes in Italy: Infodemiological Study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), Article e19374. https://doi.org/10.2196/19374

Shahi, G. K., Dirkson, A., & Majchrzak, T. A. (2021). An exploratory study of COVID-19 misinformation on Twitter. Online Social Networks and Media, 22, Article 100104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2020.100104

Shahini-Hoxhaj, R. (2018). Facebook and Political Polarization: An Analysis of the Social Media Impact on the Kosovo-Serbia Dialogue. Journal of Media Research, 11(3/32), 71–93.

Shao, C., Luca Ciampaglia, G., Varol, O., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017). The spread of fake news by social bots. arXiv:1707.07592.

Shu, K., Mahudeswaran, D., Wang, S., Lee, D., & Liu, H. (2020). Fakenewsnet: A data repository with news content, social context, and spatiotemporal information for studying fake news on social media. Big Data, 8(3), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2020.0062

Sommariva, S., Vamos, C., Mantzarlis, A., Ðào, L. U.-L., & Martinez Tyson, D. (2018). Spreading the (fake) news: exploring health messages on social media and the implications for health professionals using a case study. American journal of health education, 49(4), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2018.1473178

Statista. (2022). Leading countries based on Facebook audience size as of January 2022 (in millions). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/268136/top-15-countries-based-on-number-of-facebook-users/

STIKK. (2019). Internet Penetration and Usage in Kosovo. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://stikk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/STIKK_IK_Report_Internet_Penetration_V3-final-1.pdf

Tagliabue, F., Galassi, L., & Mariani, P. (2020). The “Pandemic” of Disinformation in COVID-19. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine, 2, 1287–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00439-1

van der Linden, S., Maibach, E., Cook, J., Leiserowitz, A., & Lewandowsky, S. (2017). Inoculating against misinformation. Science, 358(6367), 1141–1142. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4533

van Dyk, S. (2022). Post-Truth, the Future of Democracy and the Public Sphere. Theory, Culture & Society, 39(4), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764221103514

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wardle, C. (2019). First Draft’s Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Information_Disorder_Digital_AW.pdf?x76701

Wardle, C. (2017). Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/fake-news-complicated/

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe report.

Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human Information Behavior. Information Science Research, 3(2), 49–56.

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. Lancet, 395(10225), Article 676. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30461-x

Zeneli, A. (2021). Media tradicionale përballë medias së re. Olymp.